Too often we take for granted the waterways that flow through our cities and towns. Artist Laura Wills’ public art project Creek Lore actively addresses this neglect by engaging participants in a guided walk along a short stretch of First Creek in Adelaide’s leafy eastern suburbs to explore its health, history and usage. First Creek is one of five creeks fed by Adelaide Hills rainwater. With around 25 other people, on a sunny Saturday afternoon, I participate in one of the hour-long walks.

Beginning at Marryatville High School through whose grounds First Creek runs, we stumble along the dry, rocky creek bed, duck under bridges, peer into the backyards of adjacent properties and hear several speakers discuss the creek’s environment, ownership and historical significance. There’s been little rain in May and the creek has not flowed for weeks, but last September, following a huge storm on top of a wet winter, creeks and rivers across the Adelaide plain flooded and First Creek was not spared the deluge.

The first speaker, environmental lawyer Dr Peter Burdon, outlines the Indigenous law that governed the use of the creek prior to colonisation and the British-style law that has governed it since. The creek is no longer owned as a single entity and managed as a resource, as it was by the Kaurna people of the Adelaide plain, but is now controlled by various local government bodies and private owners of the land through which it runs. Fragmented ownership and control limits effective management and allows degradation of the ecosystem. Burdon notes that there are moves to recognise the legal rights of waterways to allow them to regenerate, citing New Zealand’s Whanganui River and India’s Ganges River which have been granted legal personhood. The question is how effective legal recognition of Australian waterways might be in improving waterway management and in recognising the traditional owners of the land, and how such recognition might work in practice.

Audience, Creek Lore, photo Janine Peacock

The second speaker, Marryatville High art teacher Maeve O’Hara, tells of students’ engagement with the creek, the local environment and the heritage-listed trees in the area. There is a communal bark-collecting project, and students make artworks on the theme of the creek and its environment. Sensitising students to ecological awareness will hopefully produce a generation better inclined to environmental management than mine has been. The Creek Lore guides encourage us to collect rubbish as we walk, and despite a similar walk and associated rubbish collection having taken place a week earlier, there is still more to be retrieved.

Forager Kel Amity discusses local flora and displays a selection of edible and medicinal plants which can be found around the creek, including wild lettuce and rocket, nasturtium flowers and Moreton Bay figs. Further along the creek, Choral Grief, a community choir, give a performance, and we find ourselves in the backyard of Paula and Richard (surnames not provided), who describe changes to the creek over the 20 years they have lived there. They consider that the 2016 floods could have been mitigated by more frequent clearing of rubbish traps by local government and support the view that creek management should be reconsidered.

Further along, Laura Wills speaks of her childhood near the creek and its history and describes 19th century records of Kaurna camps along its banks. Wills has installed several evocative artworks along the creek bank, including Water, a digitised composite photo of the flooded creek printed on a large rectangle of cloth and suspended between two trees; baby birds assembled from cloth, knitted wool and gumnuts to draw attention to the loss of bird life; pieces of fabric embedded in the bank suggesting clothes and linen; and paintings on rocks lining the bank, depicting trees in the flooding rain and recalling Indigenous rock art. Participating artist William Cheeseman’s fish trap, a woven basket set into a rock barrier that funnels fish into it, shows how the original inhabitants sourced food.

Purple Spotted Gudgeon 2017, Collaborative work with Marryatville High School year 8 students

site-specific ephemeral work Creek Lore, photo Chris Reid

Our walk ends at the delightful Tusmore Park, with its barbecues, chlorinated wading pool and lush lawns amid ancient red gums. An old stone footbridge crosses the creek. There’s no trace of the 2016 flooding that inundated the park and filled the pool with mud. We’re directed to artist James Tylor’s simple installation — a metal plate fastened to a large rock in the creek bed stating, “do you know what happened here? you are standing on Kaurna country” — an unobtrusive but articulate reclamation of the site and its history. Tylor tells participants of Kaurna welcoming traditions and the process by which traditional culture and inhabitants were eradicated by colonists in the 19th century. Twenty-five years ago, I used to take my kids to this park but knew little of its history. At the walk’s conclusion, tea and cakes are served and artists, speakers, volunteer helpers and participants mingle.

Laura Wills’ account of her relationship to the creek is a very personal one, as are those of James Tylor, who is of Kaurna as well as Maori and European descent, and Paula and Richard. There is a Creek Lore blog to which people have contributed. These personal accounts prompt us to think of our own connections to place, and this seems the real point of the relational Creek Lore project — to encourage us to reconnect to place and to neighbours. Wills worked with Open Space Community Arts (OSCA) to develop Creek Lore, which is subtitled a “project of the everyday,” one of a series of OSCA projects intended to encourage community engagement.

First Creek is no longer an essential food and water source but a storm-water drain that sometimes clogs up. Community engagement has the potential to recognise the creek as an ecosystem and acknowledge traditional and current proprietors and users. Now that I’m more aware of the history of the area, I feel a greater sense of connection and responsibility. Practical steps beyond this project are unclear, but community engagement and activism at the local level can establish an important foundation in addressing broader social and environmental issues.

–

Laura Wills and OSCA, Creek Lore, Marryatville, Adelaide, 13 & 20 May 2017

Top image credit: Embed, 2017, site-specific ephemeral work, Laura Wills, Creek Lore, photo Juha Vanhakartano – Valo Productions

Prior to the 1970s few, if any, Australian regional cities could boast their own professional theatre company resident in a dedicated venue and producing ground-breaking experimental work. With The Mill Community Theatre, Geelong in Victoria was one of those few. Meredith Rogers’ book The Mill: Experiments in Theatre and Community, presents a reflection on and close analysis of one of the pioneering community theatre companies in Australia.

The late 1970s was a period of rapid expansion for theatre in Victoria, with the Australian Performing Group, the Melbourne Theatre Company, a thriving live comedy scene and the seeds of the professional community theatre movement beginning to germinate. Around Australia companies such as Sidetrack and the Popular Theatre Troupe developed strategies for engaging and developing new audiences from their local geographical area. In Melbourne this included W.E.S.T., the Murray River Performing Group (MRPG) and Theatre Works, all driven by graduates of the Peter Oyston-led VCA School of Drama, companies that would go on to make important contributions to fringe and alternative theatre in the 1980s.

As the Oyston course was launching in the mid 70s, James McCaughey had been working at Deakin University in Geelong to establish a new drama studies course which included provision for a university-owned and operated theatre space in The Mill building (a decommissioned woollen mill) on Pakington Street. Out of that space, McCaughey launched The Mill Community Theatre and along with an evolving core of theatremakers, worked to make new performance for, about and with the local residents of the Geelong community.

The Burning of Bentley’s Hotel (1979), The Mill Community Theatre Project, photo Ian Fox

Rogers quotes McCaughey: “the great splurge of Australian theatre in the 1960s…had run its course…I was beginning to realise how much very good energy was being created in the new theatre of the 1960s and that a very great deal of Australian society was untouched by anything that happened there. I didn’t feel I wanted to be part of a ghetto art form. So one of the things that took me to Geelong was [a desire] to experiment with how theatre could matter; how it could address and be addressed by a much wider society.” This would form the central ethic of his work with The Mill. To work towards a theatre with local relevance and reaching a wide audience. To use local histories and collected contemporary experiences gathered through research and consultative practice and then given dramatic structure and represented on stage.

Many of the community companies tended to operate in relative isolation, and so each developed individual approaches to the problems of community-based theatre. They introduced new inclusive practices of audience engagement and more transgressive performance interventions, such as inviting the audience to become participating performers in the world and moving performance out of the theatre into the surrounding environment. If theatre was to be vital, it had to engage. It had to mean something personal to those watching.

Rogers’ book recounts the histories and theories that underpinned the work and the ethic of The Mill Company and its approach to community engagement and theatrical intervention. Her participation as one of the company members gives her writing a sense of embodied experience of its practice, as well as bringing a maker’s eye to the analysis of the company’s history and practices. Throughout there are many personal recollections from Rogers and others of particular works and moments of practice that stand out from the drier academic analysis and give a valuable insight into the day-to-day running of the company and its artists as people.

Rogers divides the book into discrete chapters, focusing on aspects of the company in detail. She includes a reflection on the development of community theatre itself in Australia, connecting it with antecedents in the UK, as in the work of Joan Littlewood and Peter Cheeseman; the Mill building itself, the citizens of Geelong and how they impacted on the company; a close description and reflection on the history plays — the traditionally staged performances developed by the company from Geelong’s own history; and a detailed reflection on the Mill’s public workshops series, the legendary Mill Nights.

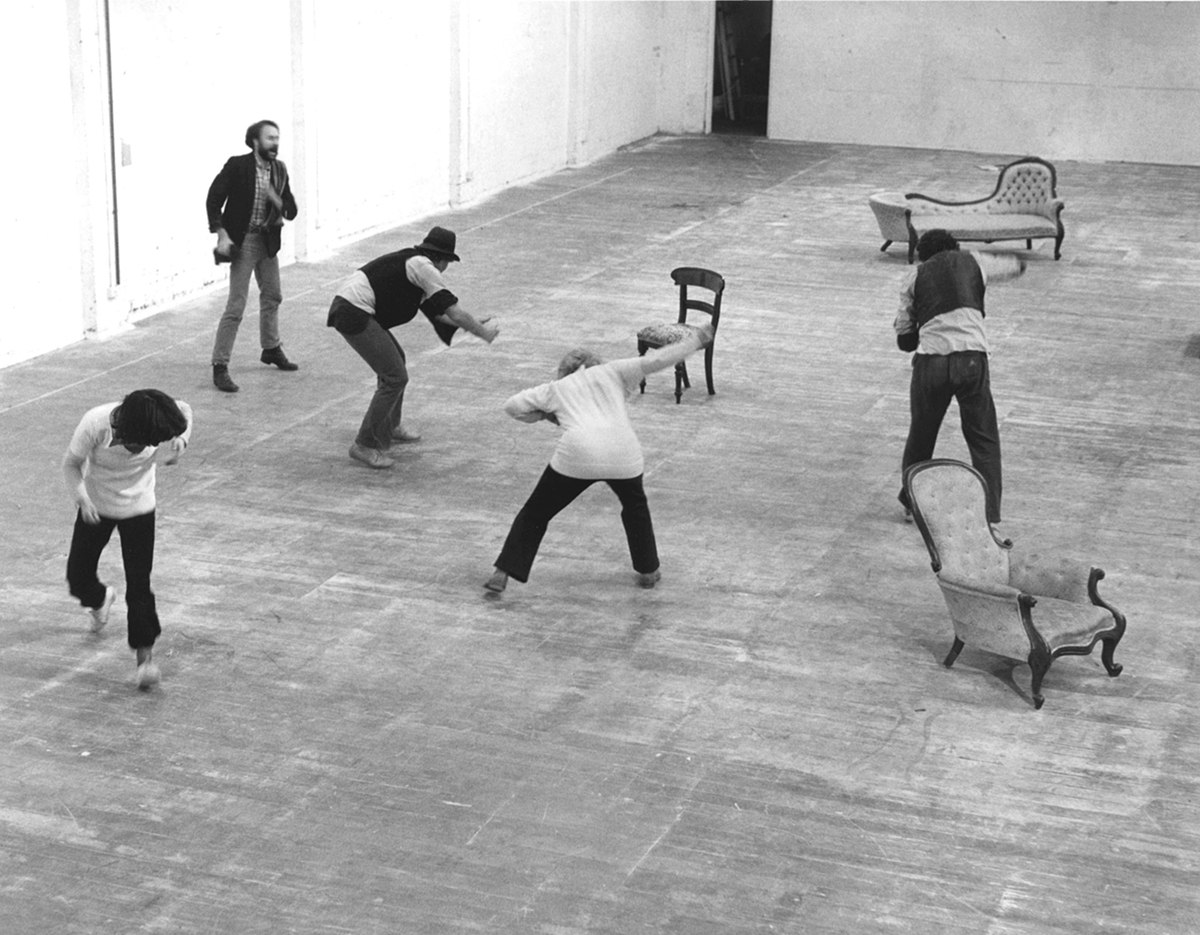

Fighting the fire at Inverleigh (1979), The Mill Community Theatre Project, photo Ian Fox

Mill Nights were regular open workshops in which the local community were invited to participate in what the company had prepared on a weekly basis. Rogers describes this night as a “simple sounding premise — that the people the company came in contact with would want to make their own theatre and that we could share our resources in order to make this happen.” The workshops initially focused on skills development but gradually gave way to large-scale participatory impromptu performance games, in which the company and the community playfully re-enacted and recreated classic movies, historic events and canonical narratives.

The end of the company, as a result of the wave of funding cuts which began in 1987, is not extensively explored. Rather, Rogers closes on the company’s many heirs and descendants, including the internationally recognised, and still Geelong-based, Back to Back Theatre.

The principles that held communities together only a few decades ago, based on locality and shared experiences, have grown increasingly diffuse and non-locative in the digital age. In response, community theatre models have evolved over time to serve communities of shared interest (such as workplace, gender and cultural identity) rather than geographic proximity.

The Mill: Experiments in Theatre and Community is a vital contribution to the history of Australian theatre, documenting an influential and ground-breaking Australian theatre company. Meredith Rogers’ book is an important unearthing of community engagement and theatremaking practice. In a post-digital age, it may be worth returning to some of these practices of community rooted in locality. Companies like The Mill — and the ethics, aesthetics and practices of the professional community theatre — might offer us a way to better understand what new models of sustainability might be.

–

Meredith Rogers, The Mill: Experiments in Theatre and Community, Australian Scholarly Publications, 2016

Meredith Rogers joined The Mill Community Theatre as actor and General Manager in 1979 and two years later she was a founding member of the Home Cooking Theatre Co, a professional feminist theatre company. She has acted in, designed and directed numerous productions, has taught in the Theatre and Drama Program at La Trobe University and written extensively on performance.

Robert Reid is a playwright, academic and theatremaker. He is Artistic Director of the Melbourne-based New Games collective, Pop Up Playground. He has written about game playing theatre in the UK for RealTime.

Top image credit: Members of The Mill Community Theatre Project working on Chairs, photo Peter Wilson

Presented as a dual channel half-hour video documentary of her 2013 project, Three Teams, Melbourne artist Gabrielle de Vietri captures an affectionate collaboration with a regional Victorian community in devising a three-team footy match, inducing footy-loving Horsham residents to question the principles of binary-driven competition. With its allegorical references to Australian two-party adversarial democracy, the project is cheekily transparent in asking local AFL fans to reimagine the rules and conventions of a sacred sporting tradition to accommodate an extra team per match.

The concept that emerges in Three Teams is “productive disruption.” Derived from pedagogical parlance, it situates knowledge transformation within certain types of activity: participant access to guided learning experiences; facilitator-participant partnership-led project development; and “thinking globally locally.”

In the video documenting the process of making the game, the club presidents express their initial reservations and quiet thrill at shepherding their members into the annals of sporting history—creating the world’s first three-sided footy game. Over six months, Vietri organises pop-up community BBQs for brainstorming sessions in the streets of Horsham, inviting local residents of all ages to pitch governance models for a three-sided game to a steering committee, using models to replicate the field (with its three sets of goalposts) and canvassing the practicalities of collaboration within competition, while remembering to sustain game flow and interest.

Echoes of Christopher Guest’s small-town mockumentary antics emerge in the second video as the game gets underway. Familiar rituals like the banner-run take place while commentary is provided by Richard Higgins (of The Listies) and footy scribe Tony Hardy, who channel Roy and HG, as the three clubs—Taylors Lake, Noradjuha-Quantong and Horsham RSL Diggers—navigate the ensuing chaos, punctuated with expressions of pride and confusion from the crowd—a heartwarming outcome for de Vietri, who clearly relishes her role as understated artistic trickster. Teik Kim Pok

–

Top image credit: From L-R: Nigel Kelly (Noradjuha-Quantongs), Jeames Offer (Taylor’s Lake), Nathan Hayden (Horsham RSL Diggers) prepare for Three Teams Football Match at Dock Lake Reserve, 2013, photo Thea Petrass, Wimmera Mail – Times

When We Talk About Food, We Talk About It From The Heart, We The People, Liveworks 2016

Where does art belong today? Outside the void of the white cube in museums and galleries, contemporary art is more present in everyday life than ever before. In shopping centres, squares, train stations and on street corners, everyone from developers to local council officers is in the business of exhibiting art in its many forms. As arts organisations continue to move outside traditional spaces, We The People placed contemporary art installations and performances in the lodgings of community organisations that surround Performance Space’s Carriageworks home. Part of Liveworks and curated by Tulleah Pearce, the project was a kind of festival of goodwill and an effort to find new ways of doing site-specific work, with artists working with small community organisations for a number of months to develop works that reflect those groups’ aims.

The rapid changes in Redfern seemed to form We The People’s unspoken undercurrent of architectural and spatial politics. Though the process of gentrification began in 2000 with Indigenous people being moved on for the benefit of Olympics tourists, the process has visibly sped up over the last five or so years. In the new Redfern, creativity is conflated with entrepreneurialism and the “creative class,” with customers for $5 matcha lattes supplanting the residents who shaped and created the value of the area’s culture and history. Along with developers, small businesses and the public sector, artists and art organisations have also played a role in gentrification, an uneasy reality that is rarely discussed within the contemporary art world.

I interpreted We the People as a sideways correction of art’s activity inside processes of gentrification. Rather than the project’s self-professed aim of examining the social fabric of the Redfern-Darlington area, the works were more celebratory in nature: a way to praise the handful of non-profit groups remaining in the area and for Performance Space to relate to its local community (a bit like its Microparks projects in 2013-14). Or maybe just to create pleasant spaces for people to spend time in for half an hour on a weekend arvo. It was a reminder that even when they’re not highly visible, small community spaces persist in this war of urban attrition, and perhaps that gentrification can never be entirely successful.

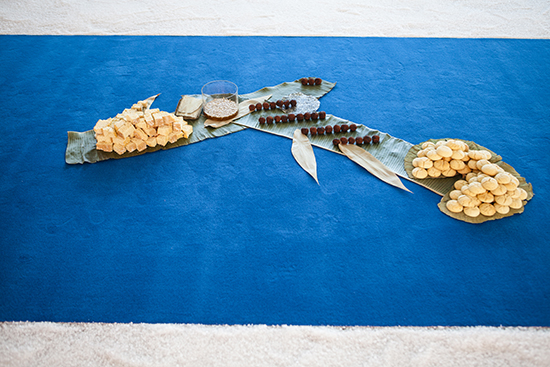

When We Talk About Food, We Talk About It From The Heart, We The People, Liveworks 2016

It’s not just the presentation of work in public spaces but cultural production that is changing. Interesting in its aim if not always its manifestation, We The People’s faults are reflective of a broader trend I’ve noticed in festival-like engagements by small to medium arts organisations in which the works have a strong core concept not fully realised: resulting in a certain flatness and unripeness. This is not a criticism of Liveworks per se but more a worrying tendency in the arts ecology: I fear there’s not the time and space and funding available for curators to develop work—to mentor artists from a project’s conception to presentation.

To me, the most engaging of the four We The People projects were the ones that engaged members of community organisations in the process of making the work. Anna McMahon’s project used Indigenous foods as the sensory trigger for a whole range of community bonding activities. The work titled When we talk about food, we do it from the heart, took place at Yaama Dhiyaan, a hospitality training centre right next to Carriageworks, specialising in Indigenous food and culture. McMahon laid the length of the room—a standard office-y space—with a large blue carpet, laced with a perimeter of rock salt. We took our shoes off to approach the rug, along which were laid small piles of delicious food made at Yaama Dhiyaan. Damper baked fresh that morning could be dipped into a bowl of honey and sunflower seeds, and shortbread biscuits and chocolate lavender truffles were laid on large leaves. People sat and walked around and chatted and chewed as they pleased; McMahon created a nice space for people to hang around and meet other art-goers.

The project clearly involved members of the host group in a meaningful way, this time, Aunty Beryl van Oploo, and other community members who were visible and active during the exhibition, replenishing the food and just generally being around. Writer Rebekah Raymond from Humpty Doo, NT, provided text which was projected as a backdrop to the long exhibition space. Much installation art functions on a very intellectual level, but it was satisfying to engage in a tactile manner beyond visuals: big crystals of rock salt between the toes, tasting sticky honey, crumbling shortbread and still-warm damper.

Audience participants, Exercise Your Rights, We The People

Likewise, Deborah Kelly’s By George! Exercise Your Rights at the Association of Good Government, had a spirit of earnest light-heartedness. The Association is an idealistic group dedicated to reforming the current political system, its home an unassuming red-brick structure I had walked past hundreds of times before, facing Redfern Station. On a modest square of astroturf, we audience members took part in some gentle exercises led by softly-spoken Association member and fitness instructor Timothy Lum, who just seemed like a really nice guy. We rolled our wrists and walked gently on the spot while Kelly intoned some of the Association’s core ideas: “against privatisation, a philosophy of equality.” Dance academic Julie-Anne Long then guided us through movement-based mindfulness exercises, drawing our focus to small sensory aspects of the site—the feel of the turf underfoot, the sound of trains alongside us, a banner by Kelly and Leigh Rigozzi depicting Association members—and inviting us to make eye contact with each other as we walked. A wide basket of apples sat at the exit, so we could replenish ourselves with the fruits of society’s labour.

The set-up was spare but suffused with Kelly and Long’s ‘come on board’ energy. The simple, neat, unifying metaphor of exercise really worked: there was a feel-good atmosphere, everyone could participate and it generated that vibe of ‘being up for it,’ which good participatory art projects tend to do. A humble, neighbourhood project, it reminded me that art can be a gesture of kindness and generosity, an invitation to participate.

………..

For the other two works in We The People, Benjamin Forster’s Kelkaj Fragmentoj at Esperanto House, and David Capra and Emma Saunders’ See you at the Top, on a Redfern street corner, see our Liveworks overview.

Performance Space, Liveworks Festival of Experimental Art, We the People, curator Tulleah Pearce; various locations, Redfern, 20-30 Oct

RealTime issue #135 Oct-Nov 2016