Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Cold time, in these southern trees the sap is running now, so I cut bark for coolamons with my son. I’m working on a shield as I begin to prepare for the season of Law, ceremony and initiation, fast approaching in the next few months. It is a propitious time for me to view Aaron Petersen’s documentary Zach’s Ceremony, which follows the journey of a young Aboriginal boy and his father from 2005 to 2016, when the boy becomes a man and goes through ceremony, comes into Law.

I approach the film with trepidation, glimpsing on the internet excited claims of “never-before-seen footage of secret initiation ceremonies!” I worry that Men’s Business images will be shown to women and children, that our gendered controls of sacred knowledge, designed to protect the agency of both sexes, will be compromised. My fears are allayed as I find that only the pre-ceremony business involving the whole community is exposed. But the film opens another can of worms for me, in its exploration of the destructive intersections between Western masculinity and Aboriginal manhood.

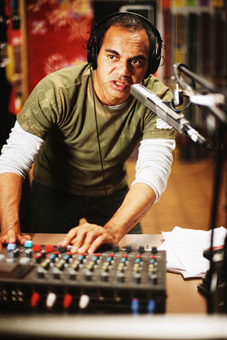

Alec Doomadgee, Zachariah Doomadgee, Zach’s Ceremony, still courtesy Umbrella Entertainment

Alec Doomadgee, a Waanyi, Garawa and Gangalidda man from the Gulf country up north, culture man and role model, is attempting to act as a one-man-village raising his son, Zach. Struggling alone in the city to provide the nurturing support traditionally undertaken by multiple aunties, uncles, parents, grandparents and older siblings, Alec is confounded by a conflicting imperative to forge his son into a fine example of the contemporary ‘Indigenous success’ mythology — an enterprising, neoliberal individual who is equally at home in lap-lap or blazer. But this story is not about him — it is about a boy who longs to come into his own knowledge and identity from the unenviable position of being the son of a great man.

His father’s presence looms large both in Zach’s life and onscreen, in a struggle that is sometimes awkward, sometimes poignant. The film is not narrated, although often it feels like Alec is attempting narration in front of the camera, or to curate his family’s story in the public domain. It is difficult for any Aboriginal person, though, to avoid tour-guide registers when coming under the white gaze. That is how we survive in this colonial economy. An animated montage of the history of Indigenous dispossession in Australia would work as a standalone introduction to Indigenous issues for novices, but is an unobtrusive and unifying element of the film.

I wondered in the opening sequences how gender would be framed. I had a moment of worry when the first mention of a woman, Zach’s absent mother, is quite damning and followed instantly by a cut to images of simpering, bikini-clad models signalling the rounds at Alec’s boxing title match. Following his victory, Alec preaches a ‘you can do anything if you work hard enough message’ to young Zach. After this, the difference between this competitive Western masculinity and Aboriginal manhood is made shockingly clear when we see father and son on their traditional lands back up north.

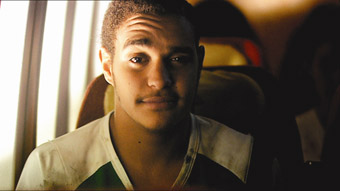

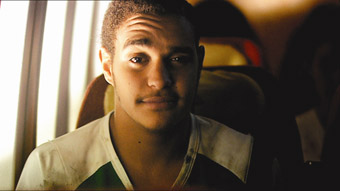

Zachariah Doomadgee, Zach’s Ceremony, still courtesy Umbrella Entertainment

This monumental shift recurs whenever they return to that remote community. Alec’s code-switching to Aboriginal English always signals a reversal from masculine bravado to a humble gentleness grounded in connection to place and people. Zach’s own shrill adolescence flips over into a rumbling, steady repartee with his cousins. Powerful local matriarchs, unrestrained by the straitjacket of Western throw-like-a-girl femininity, fill the screen and the viewer’s heart with their enormous strength and wisdom. The ceremony the filmmakers are privy to involves these glorious old ladies leading a complex process of handing over the boys for their transition into Aboriginal manhood. Talking head shots of clan elders in a variety of locations maintain interest, while some occasional gritty hand-held realism is sensitively included without overuse.

We see the chasm between traditional roles and Western masculinity when Zach emerges transformed from ceremony and returns to his father’s house in Sydney. Having been through ceremony together, there is a loving and playful intimacy that he shares with his little brother, a softness and deep capacity for care that is what true manhood is all about. But Zach reverts during his 16th birthday party to that lawless, unaccountable maleness that Anglo modernity bestows on all young men, and the viewer is at once devastated as well as relieved not to be left with a simplistic, romanticised message of ‘walking in both worlds.’

Zach’s Ceremony is ultimately not as uplifting as the adults speaking for and through Zach try to make it. But there is a truth in Zach’s eyes and words (and even his sneaky Dave Chappelle references) that triumphantly subverts the powerful genres and agendas whirling around his image, making us connect with him intimately and care deeply about his fate.

The DVD of Zach’s Ceremony will be released by Umbrella Entertainment in July.

–

Zach’s Ceremony, director, editor Aaron Peterson, writer, producer Sarah Linton, cinematographer Robert C Morton, music Angela Little, art direction Brendan Cook, associate producer Alec Doomadgee, executive producer Mitzi Goldman, distributor Umbrella, 2016.

Dr Tyson Yunkaporta is a Bama fulla currently working as a senior lecturer at Monash University, with research interests in Aboriginal cognition, methodologies, memory and pedagogy.

Top image credit: Zachariah Doomadgee, Zach’s Ceremony, still courtesy Umbrella Entertainment

Our reviewer Tyson Yunkaporta was full of praise for Zach’s Ceremony, a coming-of-age story that follows for the first time onscreen a young Indigenous man from childhood to initiation into his society, while avoiding “a simplistic, romanticised message of ‘walking in both worlds.’” Aaron Peterson’s documentary speaks of “a boy who longs to come into his own knowledge and identity from the unenviable position of being the son of a great man… There is a truth in Zach’s eyes and words that triumphantly subverts the powerful genres and agendas whirling around his image, making us connect with him intimately and care deeply about his fate.”

3 DVDs courtesy of Umbrella Entertainment.

Email us at giveaways [at] realtimearts.net by 5pm 8 September with your name, postal address and phone number to be in the running.

Include ‘Giveaway’ and the name of the item in the subject line.

Giveaways are open to RealTime subscribers only. By entering this giveaway you consent to receiving our free weekly e-dition. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Top image credit: Alex Doomadgee, Zachariah Doomadgee, Zach’s Ceremony

Goldstone

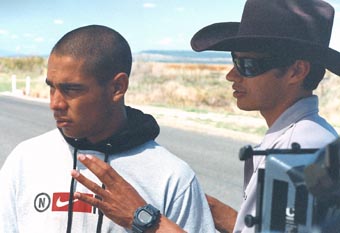

There’s a lot of dust in Ivan Sen’s Goldstone: literal dust in the desert terrain of the film’s titular town, as well as the metaphorical variety, heard from characters who talk about “cleaning the dust away.” This accretion brings to mind an image of historical detritus that cannot be brushed off, a cultural legacy that’s foregrounded during the film’s opening credits that feature a series of photographs from Australia’s Gold Rush era. Over a sweeping instrumental score, shackled Indigenous men appear with shocking clarity, followed by images of the Chinese community at work, and white Australians at afternoon tea.

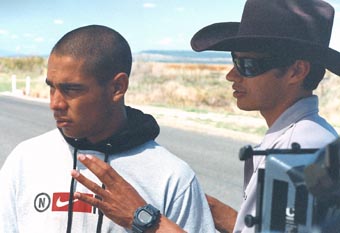

The music ceases and historical pictures are replaced by a shot of a car driving through a yellow landscape, heralding the return to the screen and the arrival in Goldstone of Detective Jay Swan (Aaron Pedersen), last seen in Sen’s 2013 thriller Mystery Road. Notably the worse for wear, he’s arrested by the makeshift town’s fresh-faced policeman, Josh (Alex Russell), for drink-driving, before being grudgingly released to begin investigating the disappearance of a young Chinese woman. Here as in Mystery Road, Swan’s inquiries start to expose something poisonous within the entire community. Goldstone might be small and relatively isolated, but the problems Swan must tackle, of exploitation and corruption stemming from postcolonialist greed and racism, are enormous and all too familiar in reality.

Goldstone

Sen is a versatile director who can move from the most meditative ‘art’ cinema (Beneath Clouds, 2002) through naturalism (Toomelah, 2011) to the skilled employment of suspense and action in his genre pieces featuring Jay Swan. But in all these films there’s a common socio-political thread of characters caught between worlds: a questioning of what it means to belong and whether it’s possible to escape your allotted place. In Goldstone, Sen takes Swan’s outsider status, as flawed but principled Indigenous lawman, and pushes it into mythic territory, intensified by his most explicit exploration of spirituality yet, centred on local elder Jimmy, played by David Gulpilil.

Perhaps this mythologising—though not a flaw in itself—and the number of problems Goldstone seeks to encompass makes the film’s approach to real victimisation seem at times superficial. For all the talk of dust, the film doesn’t feel viscerally dirty enough. The horror of sex trafficking is skirted around, while characters like David Wenham’s mine foreman and Jacki Weaver’s mayor, who with a penchant for baking and corruption is a cruder version of her truly frightening matriarch in Animal Kingdom (David Michôt, 2010), are too broadly drawn to be deeply menacing. Sen doesn’t utilise the intense close-ups of Mystery Road: that portrait-like scrutiny of faces behind which lurk potentially devastating secrets. The secrets in this mining town are fairly open ones. Swan and Josh know how the land lies; it’s largely a question of whether they can shift a few monoliths.

While Goldstone’s mythic quality might simplify some of its themes, it doesn’t reduce the impact of Jay Swan, whom Pedersen renders as layered and believable as he is archetypal. Along with ABC TV series Cleverman (2016), the Jay Swan films mark the long-overdue arrival of Indigenous (super) heroes, as well as narratives that grapple with contemporary injustices via the myth genre. Cleverman has been approved for a second series; I’m hoping Jay Swan will surface in another troubled town a few years hence.

Goldstone

Goldstone, writer-director Ivan Sen, cinematography, editing Ivan Sen, score Ivan Sen, Damien Lane, production design Matthew Putland; distributor Transmission Films, 2016

RealTime issue #133 June-July 2016

© Katerina Sakkas; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rowan McNamara as Samson, in Samson and Delilah

photo by Mark Rogers

Rowan McNamara as Samson, in Samson and Delilah

[This introduction was originally written in 2009 with some minor updates in 2012. Links will continue to be added to the list below. Eds.]

Thanks to an abundance of talent, inspired Aboriginal leadership and responsive film schools and government funding bodies, Australian Indigenous filmmaking has grown from of a handful of early works in the 1980s into a steady output of award winning short dramas and documentaries from the 1990s to the present.

Individual filmmakers have been aided in successive stages of their careers by the Indigenous Branch of the Australian Film Commission (now Screen Australia) with advice, workshops, funding and the regular release and marketing of clusters of short films, the Drama Initiative Series. More than a few filmmakers have gained experience and inspiration working with CAAMA Productions (Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association) in Alice Springs, one of several Aboriginal-led media organisations.

Sydney’s Metro Screen and FTI (Film and Television Institute, Fremantle, Western Australia) have, over many years, triggered filmmaking careers through training and mentoring. FTI, with the ABC, has produced several collections in their Deadly Yarns series of short films. State film bodies have contributed funds towards the making of numerous Indigenous films, while the Adelaide Film Festival invested in the making of Samson and Delilah.

Tracey Moffat (Bedevil, 1993), Rachel Perkins (Radiance, 1992) and Ivan Sen (Beneath Clouds, 2002) made their acclaimed feature films across almost a decade; these few were precursors to what now seems likely to be a wave of features, four premiering in 2009 alone—Warwick Thornton’s Samson and Delilah, Richard J Frankland’s Stone Bros and Rachel Perkins’ Bran Nu Dae and Ivan Sen’s Dreamland. 2011 saw the release of Beck Cole’s first feature film Here I Am premiering at the Adelaide Film Festival (which also featured Stop(the)Gap, an exhibition of international Indigenous art in motion) and also Ivan Sen’s Toomelah.

Not every filmmaker aspires to make narrative feature films: many will continue to focus on creating finely crafted, idiosyncratic short dramas and documentaries, and a small, but significant number, are now involved in exploring the potential of animation and digital media.

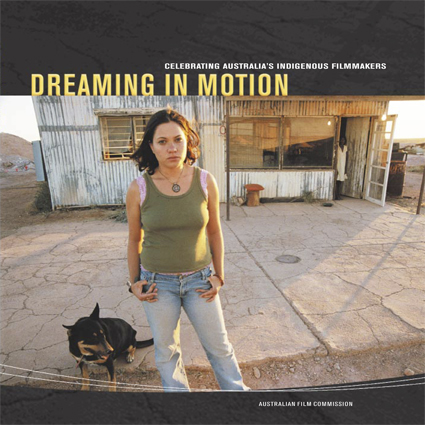

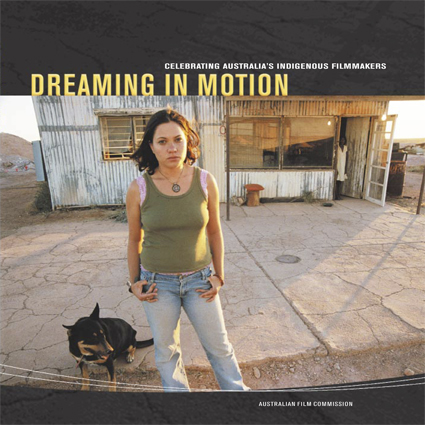

Dreaming in Motion

In 2007, RealTime edited and produced, Dreaming in Motion, A Celebration of Australian Indigenous Filmmakers. The book was published by the Australian Film Commission. It includes a brief history of Indigenous filmmaking and detailed profiles of 26 filmmakers along with production credits, festival screenings and awards. You can download the book as a PDF here. Alternatively, copies (including DVD) are available free of charge by emailing publications@screenaustralia.gov.au.

In OnScreen, our film and digital media supplement, RealTime has extensively reviewed Indigenous films and interviewed the filmmakers. The following is a selection going back to 2002.

Keith Gallasch

commentary

broken mothers in the blind spot

kathleen mary fallon: the blind side, jedda, night cries, blessed, australia

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 p28

for and by the community

gem blackwood: u-matic to youtube: indigenous community filmmaking

RealTime issue #98 Aug-Sept 2010 p32

Editorial: lessons from the indigenous sector

dan edwards

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 p18

interviews

hope & survival in the back of a van

dan edwards: interview, warwick thornton, mother courage, acmi

RealTime issue #113 Feb-March 2013 p22

a life retrieved

oliver downes: interview, beck cole & shai pittman, here i am

RealTime issue #103 June-July 2011 p13

the making of samson & delilah

keith gallasch: warwick thornton interview

RealTime issue #90 April-May 2009 p24

a filmmaking life

lisa stefanoff: interview with beck cole

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 p19

what the listener sees

lisa stefanoff talks with sound recordist & director David Tranter

RealTime issue #75 Oct-Nov 2006 p15

feature film

real life on the edge

oliver downes: ivan sen’s feature drama, toomelah

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 35

dreaming unanimity

keith gallasch: rachel perkins’ bran nue dae

RealTime issue #96 April-May 2010 p20

eddie & charlie, kings of the road

keith gallasch: richard j frankland’s stone bros

RealTime issue #92 Aug-Sept 2009 p28

the seeing ear, the hearing eye

keith gallasch: warwick thornton’s samson and delilah

RealTime issue #90 April-May 2009 p23

the story of a story

keith gallasch: beck cole, the making of samson and delilah

RealTime issue #93 Oct-Nov 2009 p28

playing by the rules

sandy cameron: ten canoes

RealTime issue #73 June-July 2006 p18

language as simple as a look

mike walsh: beneath clouds, ivan sen

RealTime issue #48 April-May 2002 p13

adelaide film festival 2011

indigenous media art: complex visions

tom redwood: stop(the)gap, adelaide film festival, samstag museum

RealTime issue #102 April-May 2011 p23

the magical meeting of cinema & media arts

keith gallasch: here i am, beck cole, tall man, vernon ah kee, tracey moffatt, stop(the)gap

RealTime issue #102 April-May 2011 p21,22,25

living cultures, moving images

stop(the)gap: international indigenous art in motion

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 p30

message sticks festival

finding the words

jane mills: message sticks film festival

RealTime issue #86 Aug-Sept 2008 p23

breaking the silence

dan edwards: message sticks

RealTime issue #62 Aug-Sept 2004 p23

new blak films

dan edwards

RealTime issue #56 Aug-Sept 2003 p18

colourised festival

the medium as the message stick

erik roberts: colourised festival 2005

RealTime issue #69 Oct-Nov 2005 p20

mirrors on aboriginality

erik roberts: colourised festival 2003

RealTime issue #56 Aug-Sept 2003 p18

caama

CAAMA: from the heart

lisa stefanoff

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 p19

short film & animation reviews

animating dreaming into action

danni zuvela: big eye aboriginal animation from canada & australia

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 p26

hybrid lives, hybrid dreams

keith gallasch sees some deadly yarns from fti

RealTime issue #85 June-July 2008

the art of the short short

keith gallasch looks into the AFC’s bit of black business

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 p23

small tales and true

simon sellars asseses australian short film at the melbourne film festival

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 p19

the art of 5-minute statements

sarah-jane norman: deadly yarns, abc-tv

RealTime issue #67 June-July 2005 p23

life behind a curtain

keith gallasch: maya newell’s richard, angie abdilla’s wanja

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008

films making culture

michelle moo

RealTime issue #68 Aug-Sept 2005 p33

michael riley

michael riley: photographer & filmmaker – part 1: spirit, land, image

dan edwards takes in the NGA riley retrospective

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 p20

michael riley part 2: the films—buried histories

dan edwards reflects on the NGA riley retrospective

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 p15

obituary: michael riley

djon mundine oam

RealTime issue #63 Oct-Nov 2004 p53

Frances Djulibing, River of No Return

WHERE YOU SEE A FILM, HOW IT’S PROJECTED, THE CONTEXT IN WHICH YOU SEE IT, AND WHO YOU SEE IT WITH CAN OFFER NEW INSIGHTS NOT ONLY TO THE FILM ITSELF BUT TO CINEMA AS A WHOLE. WATCHING THE DOZEN FILMS IN THIS FESTIVAL JUST AFTER AN AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT HAD FINALLY SAID ‘SORRY’ TO THE STOLEN GENERATIONS REINFORCED THE SENSE THAT RECONCILIATION, IF NOT TOTAL LIBERATION FROM THE PREVIOUS GOVERNMENT’S HUMAN-RIGHTS DENYING INTERVENTIONIST POLICIES, WAS NOW WELL AND TRULY ON THE FILMIC AGENDA.

The feeling of liberation from the past was heightened by the mix of red carpet partying and self-congratulation along with self-criticism and some extraordinary films and very heated discussions. Then there were the Chooky dancers who threatened to upstage everything in sight. The cultural vectors of these young Elcho Islanders simultaneously performing homage and send-up of Theodorakis’s Zorba as they spilled over from screen (Frank Djirrimbilpilwy Garawirritja’s Yolngu Djamamirr/Aboriginal Fishermen) to live on stage and onto the Opera House forecourt, offered a vision of cultural transformation endorsed by many of the films.

As in previous years, curators Darren Dale and Rachel Perkins offered the chance to see films that might not otherwise be seen at all and in circumstances that made it possible to observe patterns and samenesses as well as disruptions and differences that might otherwise go ignored or unobserved. They included films by indigenous filmmakers from overseas, allowing us to explore the connections that do or don’t exist between Aboriginal cinema and other indigenous cinemas.

In fact, the overseas films forged links to other cinemas entirely. Kevin Burton’s experimental Nikamowin/Song (2007), for example, deconstructs and reconstructs the Cree language with such inventiveness that it seemed the productive outcome of a head-on clash with Derrida and the German-Australian experimentalist, Paul Winkler (see Alec Gerbaz, “Innovations in Australian Cinema: An Historical Outline of Australian Experimental Film”, NFSA Journal, Vol 3, No 1, 2008).

Sikumi/On the Ice (Andrew Okpeaha MacLean) initially seems to be indebted to Atanarjuat/The Fast Runner (Zacharias Kunuk, 2001)—both are in a dialect of the Eskimo-Aleut languages group, both have a mise-en-scène dominated by wide, flat icy vistas, seal-skin encased bodies and whiskers with dangling icicles, and both tell a murder tale. At second sight Sikumi appears to be the offspring of an unruly union between indigenous, art and mainstream cinemas.

The boundaries between cinematic and other cultural categories proved even more porous with the Aboriginal films. A persistent theme was that of shifting ideas, images, sounds and other cultural material passing to and from Indigenous and mainstream cultures. As films such as Ten Canoes and Rabbit Proof Fence demonstrate, this is a two-way ticket.

In Darlene’s Johnson’s River of No Return, the captivating Frances Djulibing dreams of being Marilyn Monroe: sexy and a great comic actress with diamonds for a best friend. Frances’ long trudge along the dirt road between her home and Raminginging in north eastern Arnhem land becomes the symbol of the seemingly impermeable borders between Aboriginal and balanda (white) cultures that Frances must learn to cross.

The high walls white society has erected around its black members seen through Kelrick Martin’s unflinching lens in Mad Morro are too rigid for any productive interactions to take place. When released from jail after 13 years inside, there is no after care program available for 30-year old Morro to learn how to be an adult outside the prison walls; a lethal mixture of alcohol and his acquired helplessness lands him back where he started. But the film shows us what once might have been either dismissed—or hated—as a negative image of Aboriginal people. This documentary bravely crosses yet another border in search of a common humanity that knows no apartheid and shows us images that we’ve seldom seen on the screen.

Perhaps the most startling film of all is Debbie Carmody’s Courting with Justice which reconstructs an Indigenous Customary Law Court to ‘try’ the white pub manager cleared of charges of the manslaughter of Kevin Rule, a member of the Ngadju Nation. Fact and fiction, past and present, white and black truths all merge and inform each other in this outstandingly bold, intelligent film. The fear on the face of white actor Roy Billing playing the accused when confronted by the dead man’s family is as real as the grief of the family members. Like the classic Two Laws (Carolyn Strachan, Alessandro Cavadini, 1981) about the Borroloola people’s struggle for the recognition of Aboriginal law, Courting with Justice simultaneously builds and demolishes the boundaries between black and white film cultures and between black and white laws.

There is no film in this well-curated festival that does not explore the productive outcomes of cultural clashes. Even the most conventional, When Colin Met Joyce (Rima Tamou), is ‘about’ the mixed race marriage of Colin and Joyce Clague and explores the hybridised race-and-politics cultural family environment that together they created. On the far side of convention is Cornel Ozies’s Bollywood Dreaming with its snapshot of 16-year-old African-American-Aboriginal Jedda Rae Hill who skates, boxes and adores to dance to Bollywood movies (RT85, p18).

Storytime (Jub Clerc) mixes fiction with autobiographical experience. Who Paintin’ Dis Wandjina? (Taryne Laffar) explores reactions to the white graffiti artist who paints the symbol of the creator of fertility and rain for the Mowanjum Aboriginal peoples in the Kimberley in the wrong place and without permission (RT85, p18). Even the films most specifically Aboriginal in terms of content, Alan Collins’ beautifully mesmeric Spirit Stones and Angie Abdilla’s artfully creative Wanja: Warrior Dog don’t hesitate to explore the flows between tradtional and modern, fact and fiction, mainstream and non-mainstream.

When cinematic genres and categories get as confused as this we need to consider what we mean by indigenous cinema. It’s a cinema relatively so new that it doesn’t yet have a commonly accepted name. Nor is there an established critical framework in which to theorise it. Is it a single cinema that straddles local, national and regional borders? Is it a number of individual cinemas that can be treated as a sort of national cinema? Or is it simply a number of films that can’t yet be considered to be a cinema at all?

The term ‘indigenous’ is not appropriate because it can refer to something that is ‘native’ to a particular area—Dr Who, for example, is indigenous to the UK. While ‘Aboriginal’ makes sense in the context of Australia, it can cause confusion among those in other nations unaware of the significance of the capital A. Scholars, meanwhile oscillate between Third World, Third Cinema, marginal, anti-racist, multicultural, hybrid, mestizo, postcolonial, transnational, imperfect cinema, cinema of hunger, minority, minor, accented, intercultural and transcultural. First Nation may overcome many of the problems because it explicitly recognises the original inhabitants of colonised territories, though it shows few signs of catching on.

This is more than an arcane debate because, despite considerable ethnic, racial, language and other cultural differences, the various names all tend to present a single homogenous cinema engaged in political and aesthetic opposition to mainstream cinema.

It tends to be treated as a minority cinema alongside other non-mainstream cinemas with which it’s widely thought to share a common experience of being dominated and excluded by mainstream commercial cinema. Or, within postcolonial discourse, it’s treated as a sub-genre of a national cinema. Either way, indigenous films carry a set of cultural baggage supposedly differentiating them from mainstream, commercial Anglo-American, white cinema. It is commonly regarded as mainstream’s indigenous other.

Every year, the Message Sticks films show the cinematic terrain to be more varied than widely imagined. The relationship between First Nation and dominant cinema is by no means one of perpetual opposition and assimilation: minor cinemas are not necessarily cultural losers and mainstream cinema does not necessarily and continuously absorb and destroy its First Nation others. But it should be acknowledged that First Nation films usually form a part of a national cinema, and because Hollywood is the dominant cinema in most of these nations, First Nation filmmakers can find themselves as Sally Riley, Director of the Australian Film Commission’s Indigenous Branch, once said, “on the fringe of the fringe of the mainstream” (Philippa Hawker, ‘Black Magic: Aboriginal films take off’, The Age, June 19, 2002).

First Nation cinema’s relationship to the mainstream is certainly not one of equality. But this does not mean that the indigenous cinema is inevitably and necessarily crushed, contained or cannibalised by an undeniably powerful dominant cinema. The productive outcomes of tensions in the globalising processes show that locating Hollywood and First Nation cinema within each other is not necessarily an indication of cultural cannibalisation and that much greater diversity exists in Hollywood’s First Nation ‘others’ than is commonly imagined.

–

Sydney Opera House in association with Screen Australia and Blackfella Films, Message Sticks Indigenous Film Festival, Sydney Opera House, July 4-6; Tandanya, Adelaide, Aug 7-10; Deckchair Cinema, Darwin, Aug 21, Sir Robert Helpmann Theatrem Mt Gambier Aug 28-30

RealTime issue #86 Aug-Sept 2008 pg. 23

© Jane Mills; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Back Seat

IN THE WAKE OF TROPFEST, INCREASINGLY SHORT SHORT-FILMMAKING HAS BECOME A FECUND TRAINING GROUND FOR WOULD-BE FILMMAKERS AND OTHER FANTASISTS USING LOW COST, HIGH-TECH EQUIPMENT AND FILLING THE LISTS OF EVER PROLIFERATING SHORT FILM FESTIVALS OR BROADCASTING THEIR DIY ON YOUTUBE AND ELSEWHERE. WILL A VIABLE MARKET FOR SHORT FILM ONLINE, ON-PHONE, IN I-POD EMERGE IN TANDEM WITH THE RUSH OF SERIOUS NEW MAKERS? PERHAPS THE AUSTRALIAN FILM COMMISSION’S INDIGENOUS BRANCH THINKS SO.

The wonderful short films of 10-30 minutes (and several 50 minute features) that came out of the AFC Indigenous Branch’s Sand to Celluloid initiative over some 12 years provided evidence of a talented generation putting to good use the carefully constructed programs and partnerships available to it (involving the AFC, SBSi, FTO, Film Australia and other screen organisations and committed individual producers). The Indigenous Branch’s latest initiative, however, has gone with the trend, commissioning 13 five-minute films, offering more opportunities for a larger number of mostly emerging filmmakers than the three to six films made for each of the earlier programs.

Aptly titled Bit of Black Business, the films made for the initiative are precisely that, works tackling issues that continue to preoccupy Aboriginal people and their filmmakers. They attempt to sustain a collective sense of culture and individual dignity, often against great odds, but not without wry humour. In this collection, there’s a marked sense of the viewer engaging face to face with the characters. It’s as if, in grappling with limited duration, the makers have for the greater part decided to work intimately, creating brief narrative episodes from larger lives and shooting often in close-up and frequently with faces looking into the camera. The point of view of children, adolescents and young adults is recurrent as they admire or are mystified by or painfully detached from people much older than themselves.

In Michel Blanchard’s Custard, a young woman visits her home in beautiful waterside country to see her grandmother whom in the voiceover she recalls as tiny and unwell, but also how she made custard for the family. The house is not one she recalls lovingly, deploring the memory of a sick old grandfather shuffling about in the night. She sits with the grandmother in the kitchen and then by the water, the depressed older woman worrying at what killed her husband—alcohol, cancer, schizophrenia (“We’ll all get it now. Oh well, what’s one more thing?”). Back in the kitchen, the young woman pretends to read to her grandmother from the death certificate: “You know what killed him? Acute custardisation.” They laugh and, for a moment, the darkness is dispelled. It’s all that can be done and perhaps it’s enough. She leaves. Murray Lui’s cinematography glows with the glitter of sun on the water and there’s almost a sense of nostalgia in the warmth of the light on the greens and browns of the countryside. It’s just right in tempering the sadness the film generates, that sense of melancholy about the distance between the older and the younger woman. Wisely avoiding dramatic action and focussing on stillness and reflection, Custard makes its five minutes feel satisfyingly full.

Martin Leroy Adams’ Days Like These vividly portrays a growing sense of despair in the face of racism as a young black boxer, urged by his mother to find work as the household bills accumulate, barely gets to first base on most of his interviews despite looking good and behaving well. He has no criminal record but the fact that his father is in prison is enough to guarantee rejection. Beaten up by hostile white boys, he is found by cops, one of whom growls, “Hello, monkey.” It’s a brisk, blunt film, shot with a casual documentary feel. The opening, with the boy in a boxing ring, has him punching at us in extreme close-up. It’s a confronting image and the rest of the film suggests where his anger and strength might be coming from.

Back Seat by Pauline Whyman is one of the strongest films in the collection. It opens with us face to face with a 12-year-old girl in the back seat of a flash American car on her way with her white foster parents to see her Aboriginal mother, brothers and sisters. As in Custard, there’s a feeling of disconnection, again kept at a distance from melodrama and textured with a touch of nostalgia—the car, the stepmother’s hairstyle and the black mother’s home furnished with middleclass thoroughness, intriguing artworks and nicknacks and populated with neat children.

Back Seat deftly lets the story tell itself in close-ups of the girl. She doesn’t get to speak for herself—her stepmother over-eagerly listing the child’s school achievements, crowning it inadvertantly with “I don’t know where she gets it from”). The girl is too shy to communicate with her siblings who giggle at her, so she seeks refuge in the back seat of the car, winding up the window, shutting herself off from the mystery that is her life. A sister cajoles her to return for a group photo, a Polaroid shot which she fingers softly as, soon, the car pulls away and she looks longingly out the rear window. Back Seat implicates the viewer with a heightened subjectivity as we come face to face with an emotionally impossible situation, but at least there’s affection and yearning even if the distance between the child and her real family seems vast. It’s a very different account of a Stolen Generation life, but the same sad story nonetheless and based on the filmmaker’s own. (See also p19.)

Warwick Thorton is an experienced cinematographer (Radiance and many short films) and writer-director (Green Bush). Nana is his tribute to Aboriginal grandmothers. He said, on the opening night of 2007 Message Sticks Film Festival at the Sydney Opera House, venerable Nanas can do what they wish and they can be ‘wicked.’ Again, the point of view is a child’s, a five-year-old, the camera alternating between her and Nana, facing us as they see each other: Nana cooking, later Nana taking food to older people in the district, Nana conning white buyers of Indigenous art, Nana, rifle in hand, catching food (a volley of shots and a close-up of the bodies of wallabies and lizards slapped onto the bonnet of her car), Nana and an aunty on night patrol apprehending alcohol smugglers, throwing the booze into the bush and mercilessly beating up the offenders with big sticks. In a reverse shot the little girl, sitting in the car, looks on, bemused, admiring. The film is a little comic shocker made with electrifying assurance.

Jacob Nash’s Bloodlines is a simple but effective account of a young man building up the courage to telephone the mother from whom he was separated as a child. But we don’t know that until the end of the film. He lives in a stylish, comfortable apartment. He’s naked except for shorts, amplifying his vulnerability, and nervous, the soundtrack beating like a heart. He puts off approaching or even picking up the phone. We look into his face and then, with him, at the photographs of the white family of which he is a part but, at the same time, not. Nash’s approach is simple but focused and intense.

In Kelli Cross’ The Turtle, a boy in early adolesence, withdrawn, baseball cap over his eyes, earphones plugged in, arrives in a remote coastal town where he’s picked up by an uncle who takes him to where his father lived. The lone possesion is a tortoise shell: “all he left behind.” The boy won’t budge. He’s here because he’s been in trouble, presumably with the law. When his uncle can’t start his boat, the boy starts it for him, is persuaded to go out on the water and then, astonished to suddenly find himself in the water at his uncle’s prompting, flips over a turtle, thus disabling it. In a mere moment he has reconnected, however tenuously, with his father and his culture. Like Custard and Back Seat, the mood is reflective and considered, although here there’s a sense of release despite the enormous distance between son and dead father.

Sharpeye by Aaron Fa’aaso is an intruiging tale of a 12-year-old Torres Strait Ilsander boy playing spy for the local army reservists when their island is invaded during a military exercise by Special Forces. The plot is slight and we learn little about the boy, but we do get a strong sense of the pride of these part-time soldiers (elaborately uniformed and equipped with the best) and especially of their joy in victory, which they dance like their warrior forbears.

Trisha Morton-Thomas’ Kwayte has its moments and again they’re built around a child, here a three-year-old. It’s her birthday and her father has arrived home in the morning with a hangover. His wife won’t speak to him and his little daughter supplies him with glasses of water, one after the other, which intially he needs and later feels obliged to accept and which it turns out she has taken from the toilet bowl. The apparently benign “little princess” with her crown and wand has punished her delinquent father—but will she transform him? The ending feels a little thin, but the film’s construction is tight, and the little girl is engaging.

Adrian Wills’ Jackie Jackie has the look of a John Waters movie. An Aboriginal girl, Jinaali, works on the checkout in a sleek supermarket, Sunnyshine, otherwise staffed with glam white checkout chicks in plastic wigs. She hangs up a cardboard sign over her cash register saying “Equal Opportunity Line” and accrues a long ultra-multicultural queue of customers. But our heroine’s appoach is too casual for the grumpy store manager, who would prefer “ladies’ best friend” to “tampon” for her amplified price check. After he castigates her in front of the customers, Jinaali unleashes an Anthony Mundine toy on the manager and then tackles him herself, joyfully denouncing him as racist. It’s light as a souffle and good to look at, but the dialogue is clunky and the film is not as funny or political as it could be, but Wills has a certain verve. (See also p19.)

Of the 10 films in this collection that particularly appealed to me (a high ratio for a 13-film set), some handled their five minutes better than others, but most avoided the temptation to make economy versions of feature films, still a common impulse in short filmmaking where the product is seen as a stepping stone to greater things. The directors were certainly blessed with the guidance of producer Kath Shelper and the mature artistry of the cinematographers, editors and sound staff who worked with them in generating spare narratives and strong images in mere screen minutes. Bit of Black Business does its emerging talent proud, doubtless encouraging the emergence of another generation of fine filmmakers.

–

AFC Indigenous Branch, Bit of Black Business, directors Martin Leroy Adams, Jon Bell, Michelle Blanchard, Kelli Cross, Dena Curtis, Aaron Fa’aoso, Debbie Gittens, Michael Longbottom, Jacob Nash, Trisha Morton-Thomas, Warwick Thornton, Pauline Whyman and Adrian Wills, producer Kath Shelper, Film Depot, Indigenous Branch of the Australian Film Commission, SBS Independent, New South Wales Film and Television Office and ScreenWest, 2007

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. 23

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Michael Riley

MICHAEL RILEY IS PRIMARILY KNOWN AS A PHOTOGRAPHER, SO IT’S NO SURPRISE THAT HIS BEST KNOWN FILM, EMPIRE (1997), IS ALSO THE ONE MOST OBVIOUSLY ALIGNED WITH THE STYLE OF HIS LATE STILL PHOTOGRAPHY. YET IT IS THE LESSER KNOWN HALF-HOUR DOCUMENTARIES RILEY MADE FOR SBS AND THE ABC THAT HAVE HAD THE MOST SIGNIFICANT IMPACT ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS FILM.

The Australian National Gallery retrospective, Michael Riley: sights unseen, provides a rare opportunity to consider Riley’s screen work alongside his stills and brings to light some surprising correlations. Both his films and photographs employ a broad spectrum of styles, but the exhibition reveals no clear cut division between his work in the two mediums. Rather, it creates the impression of two distinct strains that cut right across Riley’s entire artistic output. On the one hand his portraiture and documentaries rely primarily on the camera’s relationship to the physical reality before the lens—the look in a subject’s eyes, the way they hold themselves, and the stories they relate to the camera. On the other hand, Riley’s more overtly abstract work relies heavily on the relationship between deliberately ambiguous images, the symbolic resonances of collected objects and the formations of the natural world.

Empire (1997) epitomises the latter strand of Riley’s oeuvre. Originally commissioned for the Festival of the Dreaming program in the lead up to the 2000 Sydney Olympics, the film went on to appear in exhibitions and arts festivals around the world. Opening with a giant eye superimposed on a cloud-specked sky, Empire unfolds as a series of images depicting the Australian landscape as a parched country devoid of human presence. Animal skeletons lie stripped and scattered on the ground; an echidna’s corpse is beset by swarming ants; a windmill spins forlornly beside two water tanks, incongruous in a land without moisture. Towards the end of the film remnants of a decaying colonial dream appear: a weather-beaten Union Jack flutters across a blue sky, a mirrored crucifix reflects passing cloud, and a burning cross evokes the dark side of the colonial project. Finally, the camera rests on a tacky ‘noble savage’ figurine of an Aboriginal man. A disembodied voice from a newsreel or ancient radio broadcast crackles in a polite British accent that belies the culturally genocidal implications of the words: “Keeping untouched natives away from white settlements where they would perish like moths in a light, replacing…their ancient beliefs…with a higher faith—the Christian faith. Training them in a benevolent segregation…gradually to make them fit into an Australian community.”

Like the concomitant photographic series, Flyblown, Empire explores the impact of European invasion on the Australian continent and its people, but unlike the photographic series, the film also illustrates the way in which Riley’s more symbolist tendencies could become heavy-handed when rendered on screen. A series of photographs can be viewed, digested and returned to in any order, creating between them a site of floating exchange crucially informed by the viewer. In Empire the images are inevitably fixed; their interpretive potential can feel foreclosed. However, it is the film’s overbearing and self-consciously ethereal music that does most to make Empire’s air of mystery feel laboured, reinforcing the sense that for all the images’ indeterminate nature, our reading is being firmly guided.

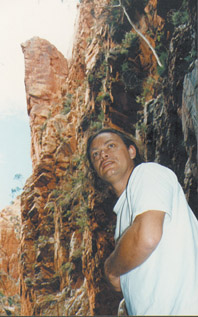

For me, Riley was more effective as a filmmaker when exploring his documentary bent in films like Blacktracker (1996), Tent Boxers (1998) and Quest for Country (1993). These typify the rehabilitative historical impulse underlying much of Riley’s documentary work. In different ways, they all seek to unearth the buried threads of Indigenous experience woven into Australia’s social, cultural and political history.

Blacktracker was made for ABC TV and examines the life of Riley’s grandfather, who served in the NSW police force from 1911 to 1950. Rising to the rank of sergeant, Alec Riley became one of the best known trackers in the country. He was instrumental in solving at least seven murders and located many people lost in the bush during his time on the force. Despite relying a little too heavily on re-enactments to make up for an absence of relevant historical footage, Blacktracker succeeds admirably in bringing Alec Riley’s story to life and portraying a warm and sensitive man who “achieved in a time of extreme adversity.” It is a positive story, but one tempered by the times in which Alec Riley lived. According to his descendants, for example, he was never awarded a police pension, despite making contributions to the pension fund throughout his working life.

The prejudices Tracker Riley encountered also adversely affected others, a point tragically illustrated by the case of a two-and-a-half-year-old boy named Desmond Clarke who went missing in the Pilliga scrub in the early 1930s. Riley was summoned to assist in tracking the boy down but his grandfather “didn’t want any blacks on his property.” Consequently the search party was unable to find the missing child. A year later the boy’s grandfather passed away and Riley returned to the area; within 12 hours he had located Desmond’s remains in a chalk pit 500 metres from the family homestead. This story later provided the inspiration for Rachel Perkins’ film One Night the Moon (2000).

Two years after Blacktracker, Michael Riley made Tent Boxers for the ABC, another film looking at Indigenous men working in a time of institutionalised racism. The boxers of the film’s title were amateur fighters who until the early 1970s toured with country fairs, slugging it out with any locals willing to take them on. Inevitably many of the boxers were Indigenous youths looking to make some money and escape highly segregated country towns. They were expected to participate in up to fifteen fights a day in large circus tents strewn with sawdust and jam-packed with onlookers. In return they received some money and the rare opportunity to travel Australia. As one pair of fighters fondly recall, there was also the attraction of ardent female fans. Riley interviews a range of former boxers, intercutting their recollections with archival footage of the fairs and the fights, creating a vivid portrait of a distinct social and historical milieu shot through with humorous tales and memorable characters. The film exemplifies documentary’s ability to bring to light prosaic, small scale stories bypassed in ‘big picture’ social histories, revealing much about the everyday minutiae of a particular period.

Both Tent Boxers and Blacktracker remain within well established television documentary forms, but the earlier Quest for Country (1993) provides a rare example of Riley pursuing a degree of formal experimentation in one of his documentaries. Quest for Country is structured around Riley’s journey to the areas his father and mother are from around Dubbo and Moree. Like Empire, the film explicitly explores an Indigenous way of viewing the land and the stories the land holds. It begins with Riley driving through and observing the streets of Sydney before he passes out of the city, over the Blue Mountains and across the western plains. His gaze is intercut with a jarring visual and aural montage of sirens, screams and photographs of smug colonial settlers staring resolutely from fading 19th century photographs. Paintings of massacres cut across apparently empty tracts of western NSW, short-circuiting whitewashed accounts of our colonial past. Interspersed with his historical ruminations, Riley presciently describes a country facing ecological disaster, explicitly linking environmental ruination with European denial of Indigenous knowledge. Throughout we constantly return to Riley’s gaze reflected in his car’s rear-vision mirror. It’s a gaze that looks both forward and back in time, anchoring the film’s perspective while also turning Riley’s stare back on the viewer. Through this subtly reflexive device, the filmmaker quietly but forcefully asserts his presence, and the presence of the stories he tells, in the country through which he passes.

The late Charles Perkins famously commented, “We know we cannot live in the past, but the past lives with us”, and it is Michael Riley’s pioneering exploration of this theme in documentaries like Quest for Country that is his most lasting influence on the current generation of Australian Indigenous filmmakers. Ivan Sen’s work in particular displays a strong thematic kinship with Riley’s films. It is through the work of artists like Riley and the filmmakers he has inspired that non-Indigenous Australians might begin to understand something of our country’s deeply repressed Indigenous history and what this history means for our contemporary situation. Until these stories are heard and acknowledged, and their implications understood, we’ll forever be like two-year-old Desmond Clarke stumbling around, lost in the Pilliga scrub, unable to make sense of the land in which we live.

–

Michael Riley: sights unseen, curated by Brenda L Croft, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, July 14-Oct 16; Monash Gallery of Art, Vic, Nov 16 2006-Feb 25 2007; Dubbo Regional Gallery May 12-July 8 2007; Moree Plains Gallery, May 19-July15 2007; Museum of Brisbane, July 27-Nov 19 2007; Art Gallery of NSW, 22 Feb 22-April 27 2008

Part 1 appears in RT76

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 15

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jindabyne

photo Anthony Browell

Jindabyne

I look at the creek. I’m right in it, eyes open, face down, staring at the moss on the bottom, dead.

Raymond Carver, “So Much Water So Close To Home”

WHEN CLAIRE, THE NARRATOR OF RAYMOND CARVER’S QUIETLY POWERFUL SHORT STORY, IMAGINES HERSELF TO BE THE DEAD WOMAN THAT HER HUSBAND HAS FOUND IN A RIVER, IT’S A MOMENT OF CONDEMNATION AND EMPATHY.

In Carver’s “So Much Water So Close To Home”, and in the recent film adaptation, Jindabyne (by Australian director Ray Lawrence) Claire’s husband chooses to continue fishing with his mates, despite having discovered the murdered woman floating downstream.

It’s this choice—to keep fishing—that provides the central ethical conundrum and terrific moral ambiguity in both story and film. But in Jindabyne the murdered girl is not just some young woman from out of town, she’s also Aboriginal. Lawrence, and screenwriter Beatrix Christian’s decision to include issues of race in this considerably extrapolated version of Carver’s story shifts the focus considerably. Several reviews have admired Jindabyne’s engagement with the theme of reconciliation, but few have examined precisely how this actually functions in the film.

Christian explores the fallout from the choice by the four men to “fish over a dead girl’s body” as the Jindabyne newspapers put it. For most of the film we closely follow the emotional and ethical struggles of our protagonists. Claire (Laura Linney) cannot come to terms with what her husband Stuart (Gabriel Byrne) has done. Much of this material—Claire’s secret, unwanted pregnancy; her past postnatal depression; Stuart’s midlife crisis (he dyes his greying hair, leers at young women, sympathises with some nearby blokes who call his wife “bitch”)—seems hackneyed (male sexual power and mateship versus female sensitivity). Yet, as many reviews have noted, Jindabyne skilfully avoids histrionics by sharply cauterising painful conversations at crucial points. But when the film broaches the huge and complicated matter of reconciliation, it falters, drawing a precarious bow from the collusion of the men (who lie to cover their negligence) to comment on Australia’s failure to confront and make amends for the suffering of its Indigenous people.

In Jindabyne we learn little about the murdered woman, Susan, or her family: the scenes dealing with their “sorry business” and their pain remain sketches. As the tensions build, the film seems at first to resist trite conclusions. Jude (Deborah Lee Furness) seethes with angry grief over her daughter’s death, withdrawing her love for the surviving grandchild (whose misbehaviour presumably stems from her own sorrow). Yet paradoxically, Jude is the least troubled by the fishing incident, despite (or because of) her husband’s involvement. “Move on”, she exhorts Claire; “let it heal over”, though her own brittle anger reveals she hasn’t managed this herself. This complexity is welcome, and true, for grief isn’t something we “get over.” Claire, the moral centre of this film, copes with her disquiet by frantically trying to make amends for her husband’s negligence. But the authenticity of her attempts at reparation are muddied by her own deception.

However this promise of complexity, confronting moral ambiguity and lack of closure is undermined by a hollow resolution. Once all the signposts about the conclusion begin to appear, the film loses its power. Having so far resisted neat homilies on personal conflict, the film invites the audience to contemplate the various human responses to an act that resists easy moral judgement. But this central conundrum is never fully realised, and when Claire and her friends gatecrash Susan’s memorial, all this good work goes to waste.

Psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva has contemplated the appropriate aesthetic response to events that overturn and tax our moral universe. She identifies, in some artistic responses to the Second World War and the Holocaust, “an aesthetics of awkwardness” and a “noncathartic representation” (Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia). Without comparing Aboriginal deaths and displacement with these events, it does seem that certain traumatic histories resist redemptive closure, and do not conform to Western (and Christian) notions of catharsis as resolution. Jindabyne suffers from trying to iron out all its awkwardness, from introducing a catharsis that doesn’t emerge organically from the central concerns of the film. What Jindabyne suggests in its penultimate scene—an Aboriginal funeral ritual—is that white people’s engagement with Indigenous culture might be a form of reconciliation. But let’s examine what really happens in this episode.

Undoubtedly, Aboriginal “sorry business”, like any community’s grieving, is an intensely private affair. But American Claire is undaunted, or ignorant of this. Impelled to make amends for her husband’s act, she arrives at the bushland memorial of the murdered girl and stands on its periphery. If Claire can just bear witness, it seems she might somehow right some of the wrong. The four men who went fishing have become town pariahs, accused of “white hate crimes”—graffiti that calls up a complex history of race relations barely touched on in the film. Three of these men have sudden, inexplicable changes of heart and also appear at the ceremony. (Given their previous reluctance to admit their wrongdoing we expect to be shown how they reached this decision, but we’re not.) Now all our central characters have invited themselves into what is presumably sacred space. Stuart is slapped and spat on by an insulted elder, but eventually stands by his wife and whispers, “I want you to come home Claire.” Her longing look suggests much is forgiven, but why? What has happened, apart from this Aboriginal ritual at which Claire and her friends are merely spectators? While the smoking ceremony proceeds, Jude arrives with her granddaughter. (Again we’re not shown why or how this came about.) They have their first moment of harmony, banishing their own “bad spirits”, saying, “be gone”.

There is something badly wrong with this scene: both as a resolution to Jindabyne’s many strands of considerable conflict and, as several reviewers see it, as a metaphor for reconciliation. As the white onlookers observe the ceremony, we sense their longing for a meaningful communal ritual of their own. Unable to gain solace from their previous attempts (a barbecue that descends into a fight, an Irish Catholic rite), these suffering characters hijack the Aboriginal ritual, which conveniently functions as the required ‘profound’ event to propel their catharses. At no point are we invited to understand the particular significance and meaning of this ritual for its black participants because we’re given little insight into the texture of their lives, or the particularity of their suffering. A syrupy English song, sung by the murdered girl’s relative is intentionally moving, but seems included for a (white) audience to better interpret the emotion of this scene. As viewers we are always positioned with the film’s central characters—as outsiders looking at a generalised scene of Aboriginality.

Because she was Aboriginal, Susan’s death has far greater symbolic meaning than the unknown victim does in Carver’s story. Her memorial offers us no genuine insight into how the film’s central characters have mysteriously resolved their considerable conflict. Consequently it seems a superficial display of Indigenous mysticism for the purpose of driving a formulaic white catharsis. If reconciliation is about adopting “colourful”, “mystical” or “deep” Aboriginal practices to provide meaning, profundity and healing for a spiritually bankrupt white culture then we have a long way to go. Unlike Carver’s narrator, who imagines herself in the murdered woman’s place, dead in the water, the characters in Jindabyne remain tourists on the edge of Aboriginal culture, too focused on their own concerns to get “right in it. Eyes open”, to wade in deep. In the most telling two lines, the film sums up its lost opportunities. Claire offers the grieving family money for the funeral, assuring them, “It’s not charity.” And they respond, “You buying something then?”

Jindabyne, director Ray Lawrence, screenplay Beatrix Christian, April Films; DVD launch date to be annnounced

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 16

© Mireille Juchau; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dayne Christian as Warren, Call Me Mum

Margot Nash’s new feature film, Call Me Mum, premiered at the 2006 Sydney Film Festival. Nash is one of the filmmakers who appears in Tina Kaufman’s contribution to our feature in this edition on the artist as educator (p17). She lectures in screenwriting at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS).

Nash started out as an actor in theatre and television, moved into photography and then cinematography and editing in the independent film sector. She’s made short films and documentaries and in 1994 she wrote and directed the feature film Vacant Possession. With Pamela Rabe in the lead role, this intense film about race and dispossession premiered at the 1995 Sydney Film Festival and was nominated for Best Directing and Best Original Screenplay in the AFI awards that year. From 1996 to 2001 Nash ran documentary workshops in the Pacific for Island women.

Engagingly intimate, Call Me Mum requires its audience to listen as attentively as it looks as a string of interlocking monologues addressed to camera unfold, alternating between locations: an aeroplane cabin, a hospital ward and a suburban home. The audience becomes confidante for the protagonists, but in discretely different ways for each of them.

Nash sticks adroitly to her formula—the protagonists never come face to face. We glean meaning from their recollections and expectations, overlapping narratives and symbolic parallels, for example around the word ‘mum.’ Even on the plane mother and stepson sit separately, occasionally glancing in each other’s direction, refusing to answer yelled slights.

Kate (Catherine McClements), white and formerly a nurse, and foster son, 18-year old Warren (Dayne Christian), are on a plane to Brisbane. He’s determined to be returned to his Torres Strait Island mother, Flo (Vicki Saylor), but risks being seized by the state and institutionalised. Kate rescued him from one such place when he was a child and condemned as irredeemably brain-damaged. She gives him a life for which, with his tunnel vision, wicked wit and abrasive sociability, he is never grateful, announcing to a TV news show that Kate stole him.

Kate addresses us frankly and assertively; she has nothing to hide, neither her love for Warren nor her anger at his betrayal. She is determined to keep him free. However, she is caught between Warren’s fantasy of reuniting with his real mother and her struggle with her own parents, Dellmay (Lynette Curran) and Keith (Ross Thompson), who live in a fantasy world of conservative righteousness (which has no place for familial loyalties).

If the aeroplane cabin looks real enough, Dellmay and Keith’s home is all floral prints and pastel lighting, cozy and self-contained, though there are moments of pained reflection and bickering over social class and bog Irish origins as well as dismay at their “mad” daughter’s adoption of Warren.

Meanwhile, Flo, propped up in a hospital bed gradually and quietly reveals to us the appalling story behind Warren’s condition, growing more honest as she goes, admitting guilt over years of alcoholism and sexual betrayal. There are moments of respite as she sings songs from her island home. She hopes to bond with Kate, to offer her a sea shell symbol of sisterhood, though she fears she will be once again be seen as ‘that rubbish.’ Finally, the hospital room around her turns lushly tropical as she yearns for her birthplace. But does the son she’s not seen since he was a baby have any place in this fantasy? Even if he does, we have just witnessed the conclusion to his journey, a nightmarish vision out of David Lynch, a cinematic jolt that removes us momentarily and shockingly from our intimate attentiveness and the pleasant cutaways to tropical island waters.

The writer of Call Me Mum is Kathleen Mary Fallon. An adventurous practitioner in experimental fiction and writing for performance, Fallon wrote the bracing, feminist novel Working Hot which won the Victorian Premier’s Prize for New Writing in 1989. Her opera, Matricide—the Musical, with composer Elena Kats Chernin, was produced by Chamber Made Opera in 1998 and in the same year a concert work for which she wrote the text, Laquiem—Tales from the Mourning of the Lac Women, was produced, composed and directed by Andrée Greenwell and performed at The Studio, Sydney Opera House. Fallon teaches writing in the Department of English at the University of Melbourne.

Fallon originally wrote Call Me Mum as a stage play, the much workshopped but unproduced Buy-back: Three Boongs in the Kitchen based on Fallon’s 30-year experience as the foster mother of a disabled Torres Strait Islander boy. The tough content and Fallon’s penchant for the surreal and the overtly political seemed to have scared off directors and producers. What was next intended as a set of 4 discrete monologues based on the same material for SBSi thankfully became a feature film in which Fallon’s vision has been subtly shaped by Nash’s own, closing in on the characters and defining their realities through Andrew de Groot’s camera and Patrick Reardon’s production design and their carefully scaled gradation of these worlds from the real to the almost illusory. This nuancing is inherent in the writing, in Kate and Warren’s stubborn directness, Flo’s lyrical, confessional musing and the bitterly and wickedly funny dueting of Dellmay and Keith.

The performers handle the language more than ably with Christian and Saylor excelling and Curran and Thompson capturing the curious poetry of righteousness with admirable restraint (Thompson’s “not sorry” tirade is both in writing and performance unnervingly beyond satire). McClements has the hardest job, the plainest and most expository text and, in delivery, sometimes borders on the theatrical. But eventually she draws us in, especially in the rare moments when her love is glimpsed and we learn how fighting for her foster son has made her “the monster Warren says I am today.”

Margot Nash is to be applauded for taking on Kathleen Mary Fallon’s unique story and giving it a very special life. The apparent simplicity of the multiple monologue structure belies many subtleties and transformations, most markedly in Flo’s growing revelations and DellMay and Keith’s developing motivation for their betrayal, while Kate and Warren appear the sorry if sometimes obtuse victims of others’ fantasies and failures. These complexities can be read in many ways. In a narrow, naturalistic feature film culture it’s critical that other voices be heard, other visions seen. Call Me Mum is a finely crafted and disturbing venture into the politics of race and the possibilties of filmmaking.

–

Call Me Mum, director Margot Nash, writer Kathleen Mary Fallon, producer Michael McMahon, director of photography Andrew de Groot, editor Denise Haratzis, production designer Patrick Reardon, composer David Bridie, Big and Little Films, 76 minutes.

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 23

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Ten Canoes

In an interview with RealTime during the principal photography of his Indigenous language cautionary fable, Ten Canoes, writer, director and producer Rolf de Heer revealed, “Ultimately, I wrote a script that conformed to the parameters that were set for me” (RT68, p22). The finished film is proof that de Heer is adroit at turning constraints to advantage in a fine tragicomedy not only of considerable historical significance, but also containing its own distinctive narrative and production elements. There is little doubt that Ten Canoes will be fittingly recognised in Australia and internationally. It has already won the Special Jury Prize at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival in the Un Certain Regard section.

The intrinsic rules placed on de Heer included the desire of his collaborators, the Yolngu people of Ramingining (local elder Peter Djigirr is co-director), to include certain ethnographic details so the film could also serve as an object of historical posterity for the community. To this end, one layer of the narrative centres on canoe building and goose egg gathering, significant rites and activities that the Yolngu wished to record as a capsule of traditional activities. De Heer uses this action as the platform for the main narrative; set centuries ago against the backdrop of these daily hunter-gatherer tasks, a Yolngu elder, Minygululu, imparts an instructional tale to his younger sibling Dayindi who lusts after the elder man’s wife. The mythic tale told by Minygululu is expressed in a sequence of flashbacks and forms the chief action of the film, and is brimming with dramatic tension including instances of mistaken identity, forbidden love and violence.

In entwining these 2 narrative strands, the film cleverly echoes the episodic and elliptical storytelling patterns of some Australian Indigenous cultures. There are discursive diversions, explorations of alternate versions of the events, and the plot’s pacing is punctuated by ruminative breaks: several times Minygululu’s story halts for a moment and the perspective returns to the goose egg gatherers. As they set camp or cook some food, Minygululu chides his brother for his impatience to hear the end of the story. A further story strand is layered in by way of a friendly omniscient narration, spoken in English with the distinctive voice of David Gulpilil giving the on screen action an easy accessibility.

From the very first diegetic exchange in the film, a variation on the ‘silent but deadly’ fart gag, it is plain that de Heer is reaching for universal resonance through breadth of humour. On the whole he is successful: it is very enjoyable to see the group of canoe-builders verbally needling young Dayindi because of his crush, and scenes involving the corpulent elder Birrinbirrin build an easy bridge between Arnhem Land of a thousand years ago and contemporary mores. Counterbalancing the moments of near slapstick is a more lugubrious tone provided by occasional reminders of the cheapness of life. Perhaps most representative of this mix is the film’s denouement which manages to match the amusing aphorism “be careful what you wish for,” with sorrowful circumstances.

Ten Canoes was partly inspired by the research and photography of anthropologist Donald Thomson, and the visual style of the film certainly is informed by his 1930s work. The goose egg scenes are shot in pristine black and white, often with a locked-off camera and are highly reminiscent of classical landscape portraiture, even the figures move minimally and slowly. Great assistance is provided by the hauntingly photogenic Arafura swamp. Contrastingly, Minygululu’s story is shot in colour with more dynamic movement within the frame, often encircling smooth steadicam shots. It is rare to see such an articulated stylistic division within an Australian film, and director of photography Ian Jones and his department are to be commended for its precise execution.

To return to de Heer’s production parameters, it was the exclusive and necessary use of non-actors that posed the biggest risk of diminishing the impact of the film, and the term non-actors here means a cast with only the most rudimentary conceptual handle on fictionalised performance. However, the cast is almost uniformly outstanding. Of particular excellence is Crusoe Kurrdal, who plays the central warrior in Minygululu’s tale with a sense of powerful fatalism, Jamie Dayindi Gulpilil Dalaithngu in a dual role as confused apprentices, and Richard Birrinbirrin in a natural comic turn as a greedy honeyeater. These performances are also attributable to de Heer’s directorial skill and his rich association with the Ramingining community.

Much will be made—as it should be—of the status of Ten Canoes as an Indigenous language film, and as an historical marker with an Indigenous perspective. But this is far more than a curiosity piece—it is a well-nuanced and strikingly designed film deserving of wide attention.

–

Ten Canoes, director Rolf de Heer, co-director: Peter Djigirr, producers Rolf de Heer, Julie Ryan. National release June 29.

RealTime issue #73 June-July 2006 pg. 18

© Sandy Cameron; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Myrtle (Louise Taylor, standing) chooses a mother for her baby, RAN

So often in film and and on television, colonial and post-colonial empathy for Indigenous cultures has been framed in terms of the experience of a white outsider whose subjectivity inevitably tyrannises ours, leaving the majority white audience wondering what those others, Indigenous people, are really like. In Australia, SBS TV has allowed glimpses, although with less and less frequency, of lives in other cultures. ABC TV has restricted us to mostly British fare and less and less of what comprises the Australian present and past. Much of the world speaks English, not just the British, so where are their films and television series? Where is Canada on our screens, New Zealand (beyond a peek), the other USA (bizarrely the ABC has now taken on The West Wing), Ireland or beyond? We occasionally experience on cable another English speaking culture. The Comedy Channel, for instance, started out with some unique and very dark Canadian comedy (featuring faces from the Atom Egoyan ensemble). The Newsroom can still be seen; a more sardonic, less ‘funny’ precursor to Australia’s own Frontline. But the pickings are thin.

In a breakthrough series, RAN (Remote Area Nurse), producer Jan Chapman and SBS have walked the sometimes barbed line between white and Indigenous subjectivities, dextrously deploying collaborators on both sides and in between, and creating a rich 6-part series which I devoured in 2 sittings. RAN is spoken in Australian English and Torres Strait Islander Creole, the subtitles unobtrusively amplifying what we can already half understand. For the engaged viewer, RAN is a cross-cultural adventure, but one which clearly expresses the limits of the journey.

The old dilemma appears to persist. The narrative is framed by Helen (Susie Porter), a white, mainland regional area nurse. It’s her voice-over (if rarely used) and it’s largely her experience of the people and events that we witness, sharing her outsider’s view. However, the condition of being the outsider is driven home with force: as much as Helen would like to be part of the community she has to acknowledge that she is not only just another nurse, but that the locals will eventually take over the services she has managed. She is not indispensable.

Helen Tremain (Susie Porter) with Russ Gaibui (Charles Passi), RAN

What RAN manages to convey through its large cast is a sense of the complexities of community life on a small Torres Strait island, one in which there is joy and celebration, beauty and serenity (each episode has its quota of lingering views, calms between emotional storms) but also the pain wrought by supersitition, alcoholism, domestic violence (inflicted by both husbands and wives), male loss of traditional status and, at the centre of the series, the limits of the local medical centre. While Helen is central to the narrative, she shares the screen with mostly Indigenous performers whose characters’ lives are carefully delineated. Some are well-known professionals (Margaret Harvey, Luke Carroll), many are first-time actors from the region including Charles Passi as Russ Gaibui, the pragmatic, charismatic chairman of the island community and father of a troubled and contested dynasty. The almost romantic encounter between Helen and Russ provides an overarching if distanced framework for the series’ narrative but is quite secondary to the counterpointing of the nurse’s view of things with the focus in each episode on Russ, his wife and 4 adult children whose dramas unfold and overlap in turn. There are many scenes which Helen does not witness, or only fleetingly and does not understand. Her white friend, and later lover, Robert (a kind of RAN Diver Dan, played by Billy Mitchell), suggests, with his cruel mix of insight and cynicism, that all Helen knows of the community is what she glimpses through windows on her evening walks.

If you only read a precis of the series, you’d suspect RAN was inclined to soap opera as the gossip, misunderstandings, superstition, jealousies and outbreaks of violence, dengue fever and struggles for power rapidly accumulate. But moment by moment, RAN is often reflective, its rhythms carefully paced so that we never forget that we’re in a small community on a remote island. Each episode offers aerial shots of the island, a coral cay, wide shots of the palm-lined streets, views through windows, and closeups in the congested interior of the medical centre. The attractiveness of beach walks and swimming find their opposites in a ‘walk against diabetes’ or the drowning of the policeman’s son as he smuggles alcohol onto the island, or the poaching of local lobster by white fishermen.

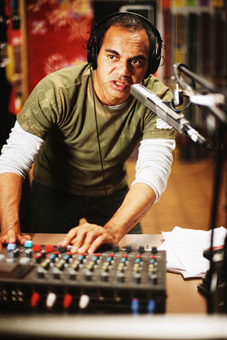

The pleasures of the island have their limits, and so do the characters in RAN and those limitations are central to its thematic thrust. Chairman Russ Guibai is a clan leader, but living in a democracy he is subject to an election, and his pragmatism will lose his office to his sons. Solomon (JIm Gela), one of those sons, is a ranger who, although married to a white woman, is otherwise intolerant of whites and limits his wife’s sense of herself. He viciously spears a pirate fisherman. Paul (Luke Carroll), the youngest brother, has been the acting head of the medical centre until Helen’s return. He has barely coped with the job but is ambitious to take it over. Paul is inadequate to the demands of his partner, Bernadette (Merwez Whaleboat) who finds the island culture stifling, the living conditions appalling and has just overcome a bout of alcoholism. The tension between the 2 results in terrible domestic violence. Later, counselled and married, Paul looks set to take over the medical centre, but RAN leaves that tale unfinished. The eldest son, Eddie (Aaron Fa’aoso), gone from the island for a decade, returns to win power through faith (he offers a kind of fundamentalist alternative to the local church run by the policeman) and the vote, appealing to a sense of self-sufficiency and idealism, taking Solomon with him as electoral partner. Unlike Solomon and Paul, Eddie is not inclined to violence. He is a dancer and an eloquent speaker and, unlike his brothers, no longer in awe of his father, no longer destructively bitter, but simply determined to supplant him. Their sister Nancy (Margaret Harvey) has reached her own limits, dropping out of medical training because of the stress, but she has an eye on the outside world and the capacity to confront her father and to challenge Helen. Nonetheless, the father’s quiet strength and his grip on power in the family and the community seems to have yielded a grim heritage compounded by the complexities of postcolonialism. The passing of his power and the departure of the nurse could signal new challenges to the limitations inherited from a colonial and Indigenous past.

RAN is in part based on the experiences of Jan Chapman’s sister as a regional nurse working on Masig (Yorke Island) where the series was filmed. The white writers, John Alsop and Sue Smith, visited Masig and Iama islands to research the series, drawing on local lives. Alice Addison joined the writing team. Torres Strait elder statesman George Mye was cultural consultant, nurse Robyn White consulted on remote area health management, actor Charles Passi gave additional advice on culture and language, and casting director Greg Apps spent 3 months in Queensland and the Torres Strait auditioning by videotaping conversations rather than by screen testing. The series was shot over 4 months on high definition tape and in terms required by the community, including no alcohol. The episode directors were David Caesar and Catriona Mackenzie (a young Indigenous filmmaker with impressive short film credits) who, with the help of a fine script, have secured excellent, intimate performances (with harrowing, explosive moments) from a uniformly strong cast. Ian Jones’ cinematography is immersive and David Bridie’s bringing together of music from the Melanesian region frames the action without resorting to melodramatic underscoring. RAN is a wonderfully sustained series that sets a new benchmark for cross-cultural collaboration and for Australian television series.

–

RAN (Remote Area Nurse), directors David Caesar, Catriona Mackenzie, producer Jan Chapman, co-producer Helen Panckhurst, writers John Alsop, Sue Smith, Alison Addison; A Chapman Pictures Production. Shown on SBS TV, Jan-Feb

RealTime issue #71 Feb-March 2006 pg. 19

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Rolf de Heer

photo Jackson

Rolf de Heer

To sustain an art cinema career in an Australian context demands an ingenious balancing act. It is necessary to judiciously work to a low budget, create innovative content and style that will attract the international marketplace, and maintain a sensibility that appeals to an Australian audience who display, at best, a distinct indifference to their local industry. It takes a consummate risk-taker, problem-solver and troubleshooter to fulfill this formula.