November 2022

Afforded the ‘luxury’ of retirement, my response to Kaz Therese’s Sleeplessness honours this little reviewed, culturally significant performance by documenting and interpreting it in warranted detail. Should Sleeplessness enjoy subsequent seasons, be warned, I describe revelatory moments in the quest Therese undertakes. At the end you’ll find links to interviews with Therese at various career stages, reviews of their works and a fascinating report they wrote for RealTime about PS122’s archival RetroFutureSpective Festival in New York in 2011.

***********

Awake, flooded with stress hormones, sticky irreconcilables, invasive visions, churning repetition, time eternal. Sleeplessness. A nice enough word to voice — sibilant, assonantal — but hellish, a waking nightmare, a haunting. This irresolvable state of uncertain being is vividly conjured by Kaz Therese in Sleeplessness, a solo performance hovering eerily between confided personal history and phantasmagorical psycho-physical projections.

On a large bare space, save for a large screen upstage and a rack of clothes to one side, a casually attired Therese slowly sets out a neat grid of documents with deliberation, eventually gathering up the great mass and introducing us to a quest — to solve a sleep-depriving family mystery for which no end of facticity has been sufficient: the elision of a couturier Hungarian grandmother from a skeletal family narrative riddled with forgetting, denial and ambiguity. “It’s the not knowing. The not knowing.” Therese’s own sense of identity and wellbeing is consequently at stake, as well as the family’s: “I thought I could stitch the family back together through art, that this would become our living archive … but that’s not how it works.”

Instead, Therese sets out on a real-world quest, poring over photographs, travelling to Hungary, interpreting documentary evidence and exploring medical symptomology. Then, in the making and performing of Sleeplessness, Therese returns to art, weaving introspection, recollection and imaginings to do something more than simply represent the quest and its provisional resolution. We witness and become empathically complicit in Therese’s reaching back into the past, leaning into the pain, charting the shuddering evolution of an incomplete self, giving it feasible shape and filling gaps with invention — with what might have been and with which to move forward. The alternative? Remain in stasis, sleeplessness, self-annihilation even.

At the centre of the mystery is a riddle: a death certificate made out not for grandmother Lenke Palffy, Hungarian, female, but for Lenki Palffy, German and male. Therese’s mother Eva, who grew up in a Catholic orphanage in Sydney, has little to say or recall about her mother, let alone what happened to her, and cannot speak Hungarian: “the nuns must have beat it out of me.” Therese’s adolescence is turbulent. “At school I had a boyfriend but at night I had affairs with older women.” Therese “runs with the pack,” misses classes, is kicked out of home by mother Eva’s drunkard boyfriend, sent unwanted to father and stepmother on the Gold Coast and later rescued by sister Mel and taken to Melbourne. But “Mel disappears and I fall apart”; “Mel becomes a ghost.” Therese works in drug and alcohol rehabilitation. There are suicidal impulses but the need to solve the riddle drives a search for meaning, and new experiences —“high in Hungary, with new friends” who help in the research.

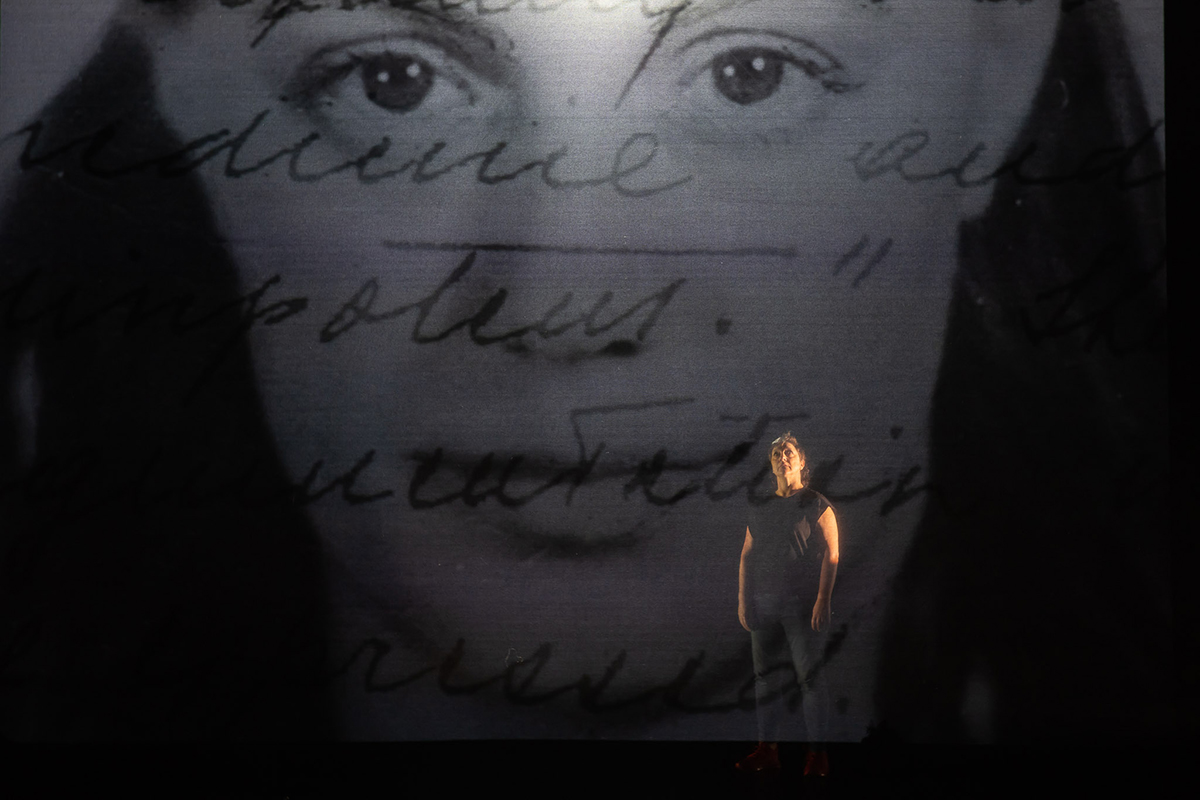

Threaded into the weave of recollection and anecdote are images writ large on the screen, including a passport photo of a woman’s face: “She was beautiful. Every time I asked my mum who she was, my mum would say ‘Oh that’s my mum.’ My mum did once say she remembers she always looked done up, immaculate. She remembers her wearing a blue polka dot dress and a short brown fur coat… And when I asked my mum, ‘Well, what was she like?’ My mum would always say, ‘Oh I don’t know love, I don’t know’ …When my mum was in that orphanage, the nuns told her that Lenke had died.”

There’s a happy family snap with Eva, Mel and the child Therese in a dress (emphatically declared a rare occurrence); a passport portrait of a young Therese; newspaper headlines about the so-called Bidwell Riot of 1981 (the housing commission youth of outer suburban Sydney denigrated by the media and the NSW government); and photographs from the trip to Hungary. There are treated images evoking a sense of attempts to match the vagaries of image with research: a stamped official document superimposed over the grandmother’s face; handwriting inscribed over Therese who elsewhere appears in various locations bleakly resonant with changing circumstances and sense of isolation. Closeups of hands, feet and limbs look for solutions, for identification.

Invention goes further in film passages featuring stylishly moody actors as mum and dad wandering between train carriages and elsewhere dancing: an idealised, reparative fantasy. Although Therese felt at the time that it didn’t work, admitting to loving a shot of the pair dancing in rain, if with a touch of bitter irony: “My mum and dad met at a dance and he danced her to poverty. How romantic.”

On film, we see Therese on a bridge in Budapest peering down into the river below, identifying for the first time physically with Lenke, where she once might have stood. Therese leans over the edge, perhaps tempted to fall, to disappear. And it seems does, only to emerge, head and shoulders above rippling, multi-coloured wavelets, as if revived, ready to quest on. A 1956 police report had recorded Lenke’s attempted suicide from Sydney’s Pyrmont Bridge. “I wondered if by becoming her in film, I might find her in real life, in my life.” The watery imagery spills immersively towards us over the shiny stage floor and the tingling zither-like buzz at the core of Anna Liebzeit’s score, framed by a visceral bass and keening strings, evokes a tense return to Hungarian origins and an abiding anxiety. (The score’s sense of unease is apparently generated by the composer’s use of “the rhythms of an insomniac’s sleep to underscore the physical act of memory”.)

A fear of death is manifest in a filmed pack of wolves recurring across Sleeplessness. Therese’s stepfather allowed the six-year-old to watch a werewolf movie on television, The Beast Must Die (1974). The consequent fear of throat-tearing wolves isn’t explicitly synced with Therese’s quest, but it underlines a sense of extreme vulnerability in the absence of a cogent sense of identity. The adolescent Therese loves American Werewolf (1981), presumably because of its evocation of outsider otherness. However, “I thought being gay was going to protect me from violent relationships but … during those relationships I became a part of the undead. I walked the earth in limbo.”

When words prove inadequate, Therese’s body opens to expressing the imagined physical abuse of the institutionalised Lenke in a painfully raw cycle of running, falling, wracked as if assaulted, and crawling. Gagging and gasping, Therese limps to the clothes rack and, in a breathtaking coup de théâtre, transforms into the grandmother in blue polka-dot dress and short fur jacket, low-heeled shoes, lipstick, a thin whispy beard, head held high, speaking Hungarian, aristocratically declaring her surname, Palffy.

Gaps in Lenke’s life are filled in: her incarceration in the Mental Home for Women — she sought treatment and was declared insane; final years in a nursing home; and the bewildering medical reason for the grandmother’s apparent masculinity, Cushing’s Syndrome, a disease of the pituitary gland leading to baldness, facial hair growth, redistribution of body fat and the clitoris growing penile — unassessed and untreated at the time (although the condition was labelled in 1932).

Therese can now declare that at 49 years-of-age, “I am here,” while “still feeling the pain” and acknowledging “the many beautiful women who have been destroyed … But I’m not one of them and that’s my choice.” Compelled by an incomplete sense of identity rather than surrendering to, Therese took on a task, to ground a ghost-like self.

Choice, however, did not come easily given the impediments of multi-generational trauma: Lenke’s disappearance and the harsh treatment and ongoing trauma wrought on Forgotten Australians — child migrants like Eva, later known as Care Leavers — banished to orphanages and children’s homes. Across three generations, Therese and sister Mel had in effect become Forgotten Australians like their mother. Apology came in 2009 from then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on behalf of the Australian Government. There’s implied reconciliation between Therese and Eva, who is a CLAN (Care Leavers Australia Network) social welfare activist. And Eva and Mel researched Lenke’s fate in the late 1990s.

Therese’s quest is seemingly complete, in the detective work and more importantly in an act of embodied imagining, re-confirmed in Sleeplessness’s final image: Therese onstage in a hospital gown walking away from us into a projected image of Therese in a hospital gown entering a long asylum-like gothic hall, at one with Lenke. For all the work’s sense of completion, however, the image is hauntingly ambiguous, of a task never fully resolvable. Sleeplessness’s projections (Margie Medlin, Zanny Begg, Tania Lambert) provide a kind of illumination, a “radiance that falls on the past” (Iris Murdoch quoting Jean-Paul Sartre; Sartre, 1953) such that, perhaps, Therese “can recall it without disgust” and “live forwards.”

In 2003 Sleeplessness was one of the most memorable productions I’d seen that year, a sparer, less complex but grippingly raw creation that has haunted me long since. Performed in the upstairs front room of the original Performance Space on Cleveland Street, Surry Hills it had an enveloping intimacy, thanks to the sheer proximity of performer to audience and projections close to human scale, blurring the actual and the real and rendering the images deeply dream-like. I wrote, “This is a space that Therese inhabits, frantically scrawling the accumulating data of the investigation across walls pinned with letters and documents and certificates, old clothes, dress patterns and strange fragments of latex, like the skin of stretch marks and ageing and torture. This is set design as installation: the curious audience inhabits it at the end of the show.” In 2022, the performer has to meet the challenges of inhabiting a much bigger stage space and performing to very large, potent projections that while hauntingly effective somewhat limit the interplay between actual body and onscreen imagery.

A much praised artistic director, producer, director and very occasional performer, Kaz Therese takes on the considerable challenge here of “just being” on stage (no easy task), engaging in dramatic movement and, for a brief critical moment, triumphantly realising grandmother Lenke. And this is 20 years on from the clearly unfinished business of the 2003 version of Sleeplessness.

With calm, measured delivery Therese sustains a sense of intimacy and quiet suspense, piecing together recollection and research and, perhaps less comfortably and more actorly, occasionally unleashing some of the underlying anger and hurt that has fuelled the quest, or awkwardly avoiding it by deploying voiceover. The relationship between projections and performer and the tonal consistency of the performance might be re-considered should Sleeplessness be mounted again, and it should be.

While the intergenerational trauma suffered by Australian First Nations peoples is relatively well documented and palpably felt in their visual art and performance, if still not understood by most fellow Australians (bring on Truth Telling), Sleeplessness gives rare voice and body to the trauma wrought on Forgotten Australians and their children. Its restless night-time oscillations between rational probing and image-driven delirium invaluably foreground a tormented, questing state of being which gradually solves a seemingly inexplicable riddle: who was Lenke and in turn who is Kaz Therese?

Tautly structured by writer-performer Therese and writer-director Anthea Williams, the intensively collaborative Sleeplessness is a courageous and emotionally exacting work, a dialectical interplay between the personal and the political imbued with a pervasive sense of tragedy: “Like Lenke, I have had my many moments on the edge of the bridge, as have my mother and sister.” From 2003 to 2022 and on, Sleeplessness continues to haunt me.

……

Kaz Therese is a writer, director, interdisciplinary artist and cultural leader. They were the Artistic Director of PYT (Powerhouse Youth Theatre) Fairfield from 2013 to 2020, creating numerous productions and events with collaborating artists and organisations. Therese has postgraduate degrees from the VCA and University of Wollongong. In 2021-22, they undertook a Creative Research residency at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), Sydney. Therese directed action film star Maria Tran in Action Star for the recent 2022 OzAsia Festival in Adelaide.

From the RealTime Archive

Virginia Baxter, Karen Therese profile, RealTime 57, Oct-Nov 2003

Keith Gallasch, “Across great divides, Carnivale: Sleeplessness,” RealTime 58, Dec-Jan 2003

Keith Gallasch, “The Evolving Performer, Karen Therese,” RealTime 62, Aug-Sept 2004

Keith Gallasch, “Condition red, Karen Therese, The Riot Act,” RealTime 92, Aug-Sept 2009

Caroline Wake, “Live work, women’s work,” RealTime 101, Feb-March 2011

Karen Therese, “Back to the past, into the future: PS122’s the retrofuturespective festival, New York,” RealTime 106, Dec-Jan 2011

Virginia Baxter, “A community fights back, FUNPARK,” RealTime 119, Feb-March 2014

Keith Gallasch, “An inclusive vision of Australian women,” interview Karen Therese, RealTime 134, Aug- Sept 2016

Keith Gallasch, “A just hearing in the court of theatre, Tribunal,” RealTime 134, Aug-Sept 2016

Caroline Wake, “Women, art & the challenges of empowerment,” RealTime 135, Oct-Nov 2016

Keith Gallasch, Karen Therese, Tribunal preview, RealTime 137, Feb-March 2017

Kaz Therese & Carriageworks, Sleeplessness, writer, performer Kaz Therese, co-writer, director Anthea Williams, Gadigal/Bidjigal Cultural Leadership Aunty Rhonda Dixon Grovenor, composer Anna Liebzeit, video artist Zanny Begg, lighting designer Karen Norris, movement choreography Martin del Amo, video consultant Samuel James, Budapest cinematography Margie Medlin, Sydney cinematography Tania Lambert, commissioner Carriageworks; Carriageworks, Sydney 4-13 August

Top image credit: Kaz Therese, Sleeplessness, photo Anna Kucera