When I'm calling you

Mireille Juchau

Merilyn Fairskye, Connected

You know when you’re approaching Pine Gap, the American defence facility 30 kilometres south of Alice Springs, says a friend from the Northern Territory. Before you catch sight of the huge silver radomes at one of the world’s largest satellite stations, you notice their effect—suddenly you have impressively crisp mobile phone reception.

Despite facilitating communication, Pine Gap has a more ominous place in the public imagination because of its role in intelligence gathering. To John Pilger, Pine Gap is an American spy base, a “‘giant vacuum cleaner’ which can pick up communications from almost anywhere”, and a nuclear target (A Secret Country, Jonathan Cape, London, 1989). The official line? It’s a joint Australian-American operation supplying the West with information about missile developments in what George Bush hokily terms “rogue states.” What no-one refutes is Pine Gap’s ability to intercept a host of signals from ships and submarines to private telephone conversations.

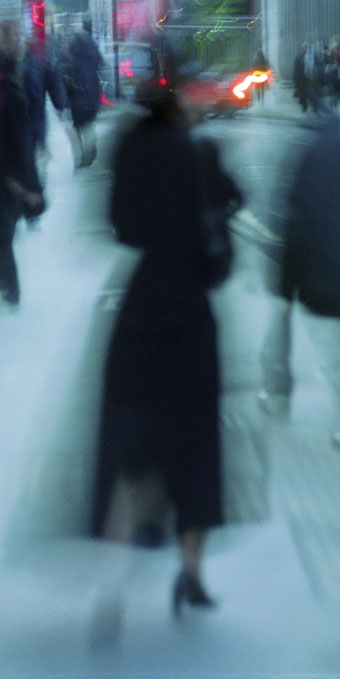

Merilyn Fairskye illustrates the eerier aspects of this global interception in her recent exhibition, Connected, at Stills Gallery in Sydney. Fairskye’s 11 photographs on rectangular, translucent surfaces, suspended at a short distance from the wall, depict life-sized figures hurrying from view. In this very contemporary version of street photography, Fairskye’s subjects rush toward their futures; they’re faceless, yet each has a distinctive ‘character’ in their gait, clothing and shape. Shot from behind, each person appears to be talking on a mobile phone, and though connected, they appear oddly disengaged from the busy urban environments in which they’re pictured. Connected suggests the paradoxical isolation that occurs despite telecommunication. The photographs, with their sharply defined or shadowy forms, avoid didacticism, but Fairskye prompts us to consider the unintended ramifications of our contemporary state of hyper-connectivity with her accompanying film on Pine Gap. Because you can hear the DVD’s surround sound while looking at the photos, the images accumulate more sinister dimensions. This sense of ‘overhearing’ something occurring in another room is a neatly reflexive (though perhaps unintended) design feature that comments on the exhibition’s themes of secrecy, gossip and intrigue.

Fairskye’s 25-minute film deftly illustrates Pine Gap’s place in the public imagination and in the local cultural and social life of the Territory. Snippets of rumour, electric currents of intrigue, inventions, myths, anecdotes and speculations about the mystery and possible functions of the facility are voiced in this work. The flows and circuits of local, everyday intelligence gathering are beautifully contrasted with the arguably ‘factual’ and ‘official’ information snared and processed at Pine Gap. From the soundtrack, between the hiss and crackle of line static, I caught grabs of chat about September 11; an Aboriginal man saying “this is my land”; someone commenting “it was clear he had no idea what his father does”; talk of a “Pine Gap Husband” and rumours of radiotechnicians diagnosed with cancer. The soundtrack is juxtaposed with abstracted footage, shot using a “Pine Gap modus operandi.” Fairskye films “from the air and from the ground—Anzac hill; the airport; the Pine Gap exit; Ormiston Gorge; Hermannsburg Mission; Kata Tjuta—to create a sense of a town and a landscape inhabited by shadows, mirages and secrets” say the room notes. Shadows move across the parched earth of the Aranda people, above stretch dramatic cloud-streaked skies, figures walk backward through a street and aerial shots render the landscape painterly. All reinforce the sense of a place in which connections and information have become disembodied; a space where, says a voice in the film, “actions and stories and events disappear into the landscape…like dust.”

These competing discourses on communications prompt questions that the photographs alone might not: do the advances in technology that ‘enhance’ communication give us greater freedom, or does the flipside of this—spying and phone tapping for example—actually erode our liberty? Do modern technologies increase our connectedness or supersede and therefore diminish our ability to interpret the intangible codes and signs of actual human contact? With the spectre of Pine Gap looming over the exhibition, Fairskye suggests the tenuous divide between the private and the public, and hints at potentially apocalyptic scenarios that might result from listening-in.

Despite their contemporary, cool feeling, the smudgy, primary colours of city signs, neon lights, and the energetic, harried feeling in the stills, each figure has a poignant solitude. Moody and translucent, the first 2 subjects are dark shapes in which you can see your own reflection. Another shot is blurred to the point of abstraction, more painterly than photographic. In appearing both rushed and stalled, these exposures are more like fast grabs from a moving image than artfully contrived portraits. And though the settings are recognisably urban, there is little to tell us exactly where these telecommuners are located, which is, cleverly, the point. Telstra spends a fortune pushing the fantasy that once we’re connected, geographic and physical boundaries dissolve, the world opens up; that we can be in more than one place at one time. But this requires a necessary disconnection from our immediate surroundings.

Fairskye’s photographs eloquently chart this dislocation: her prints seem detached, they hover on the walls; the figures are accompanied only by their shadows, dark pools on the polished concrete gallery floor.

Connected, Merilyn Fairskye, Stills Gallery, Sydney May 28-June 28

RealTime issue #56 Aug-Sept 2003 pg. 41