To do more than talk, more than please

Malcolm Whittaker, Australian Theatre Forum 2015: Making It

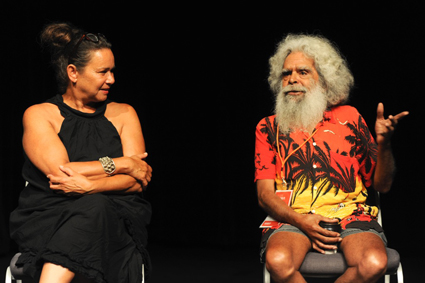

Rhoda Roberts, Jack Charles, Australian Theatre Forum 2015

photo Heidrun Löhr

Rhoda Roberts, Jack Charles, Australian Theatre Forum 2015

As part of the 2015 Sydney Festival, the biennial Australian Theatre Forum was a chance for the scattered tribes of theatre communities across the country to gather for 63 events and 140-odd speakers in and around the foyers, studios and theatres of the Seymour Centre. Curator David Williams encouraged everyone present to go on their own journey through the program on offer, even if that just meant going to the bar. The only stipulation: this gathering was not a market.

Freedom from the pressures of a marketplace allowed all manner of convivial practice-centred conversations: pragmatically bureaucratic, charmingly nostalgic, helpful and heated on matters of diversity, viability and the environment.

While perhaps lacking some of the ‘deep hanging out’ of the previous ATF in Canberra due to the draw of summertime festivities in Sydney, a provocative thread was woven about how contemporary practice lives with its history and is informed by this history into the future. What does it mean to make and present theatre today, and what will it mean tomorrow?

The forum itself took on the same form as in Canberra. Rather tenuous titles were given to an eclectic and busy mix of presentations, panels, Q&As and roundtable discussions. Rather than a single keynote speech, keynote events took place daily. This served to tell us: there is no single keynote that needs hitting for our discussions and that no one central note would suffice.

Actor, director and Artistic Director of Ilbijerri Theatre Company Rachael Maza began with the opening keynote of the forum, focusing on Australia’s Indigenous theatre history. Maza noted that politics and theatre have always been inseparable for Indigenous Australians, and from the 1960s onwards Indigenous theatre has been used as a vehicle for self-determination in action. She observed a current shift in psyche with the growing canon and programming of Indigenous works. She also remarked that we still have a way to go to overthrow the White Australia myth that power structures perpetuate. Ongoing issues remain around cultural ownership, exchange and appropriation when white Australian theatre makers engage with Indigenous theatre, stories and representation [Maza cited in particular the marginalised role of the Aboriginal characters in the Sydney Theatre Company production, The Secret River; see also RT113, Eds].

Anecdotal reflections and parables from Maza and her fellow Indigenous keynoters—singer/songwriter, author and poet Richard Frankland and actor, producer, director Rhoda Roberts—complemented the Respect Your Elders stream of the conference. This saw the likes of performance photographer Heidrun Löhr, actor Uncle Jack Charles and writer and publisher Katharine Brisbane engaged in discussions that reminded us of important facets of our theatre history, taking it beyond mythology and text-book documentation. The session on the national women’s performance writing network Playworks (1985–2006) allowed for contemporary reflection on the all too familiar issue of unequal female representation in theatre and how a previous generation worked to overcome it. We have had a recent push of female directors, but what of female writers? Elsewhere a panel on diversity debated whether a quota system would affect the integrity of theatre work and whether what is needed is a cultural shift away from perceived difficulties in attaining diversity and more towards the richness it offers.

Country Arts SA’s Steve Mayhew led a discussion on practices enabled by the growing use and interest in digital platforms and the changes these are bringing to the way we make work. It was stressed throughout that digital technologies should always be used holistically rather than simply tacked on, and should never be treated as neutral. The rationale was that technology, no longer a novelty, is central to life and consequently to contemporary practices, as tool rather than subject, enabling new ways of working and new forms of access. It is no substitute for liveness—or not yet at least. When might that be a concern? Should it be?

Living and practicing contemporaneously was approached from a different angle in a lively breakout session led by Greenie-in-Residence at Melbourne’s Arts House (see p4) Matt Wicking. The discussion focused on the growing momentum towards sustainable arts practices for the sector, pros and cons for ‘going green’ and whether didacticism works. Wicking encouraged all present to engage in personal reflection. What does it mean to be human? Are we separate from the world? What is our relationship to it?

David Williams, Frie Leysen, Australian Theatre Forum 2015

photo Heidrun Löhr

David Williams, Frie Leysen, Australian Theatre Forum 2015

For the closing keynote of the forum, Belgian festival director and curator Frie Leysen delivered an impassioned address, “Embracing the Elusive; Or, the necessity of the superfluous,” at Sydney Opera House that reflected on why we need theatre and why we should continue the struggle to embrace the elusive in a world ideologically opposed to what it represents. Leysen likened the arts to an irrational and unknown third leg that assists in supporting us. She quoted Proust on the need to see the world through the eyes of 100 different people in order to grasp it, and the idea that theatre might assist us in a continual process of unlearning and unknowing towards this. Jakarta and Melbourne based Chinese-Indonesian actor and performance-maker Rani Pramesti, a refreshing voice of an underrepresented next generation at the forum, acutely equated Leysen’s urgings to the need for decolonisation throughout theatre and all of its processes. Colonisation might be irreparable, but how we live with it is not. We might not change the world, but we can at least contribute to changing ways of thinking. The forum conversations were not about be-alls and end-alls, but about processing thought through practice, through addressing complex histories and legacies, and asking how all this might contribute to the future?

An outcome of these conversations was a Motion of No Confidence drafted by delegates over the course of the forum critical of the Liberal-National Party Australian Government’s attitude to the arts. Describing the letter as a political gesture that was symbolic at best, David Williams read it aloud with writer Vissolela Ndenzako at the close of the forum, encouraging those present to sign if they so wished (there were 52 signatories at the forum and another six subsequently). Given “the actions and ideology of the Federal government currently lead by Prime Minister Abbott,” the letter referred to “The irreparable social and cultural cost to the future of this nation [which] will be felt for generations and must be urgently resisted. “

If the protest was “symbolic at best,” the letter was properly symbolic of the forum’s conversations actually adding up to to a form of action. In the wake of wondering if talk was simply repetitive—like the scattered catch-cry that artists need to be more political—this represented a step forward from a known history into an unknown future, with a sense of hope (however symbolic). It’s what Frie Leysen urged, that we don’t simply aim to please everyone, but dare to be disturbers, and that we “valorise the risk, the adventure, the ephemeralness, the uniqueness of the experience and the temporary community that is created” through theatre.

Documentation of ATF2015 is available online including Motion of No Confidence and Frie Leysen’s Keynote address and watch Rachael Maza’s keynote.

2015 Sydney Festival, Australian Theatre Forum 2015, Making It, curator David Williams, producer Theatre Network Victoria (TNV), 21-23 Jan,

www.australiantheatreforum.com.au

RealTime issue #125 Feb-March 2015 pg. 12