Time and the theatre fix

Keith Gallasch

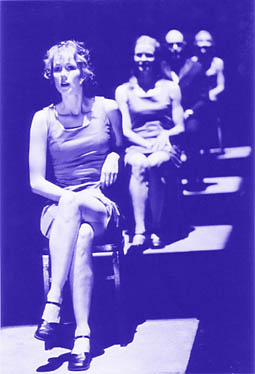

Lucy Taylor, Margaret Mills, Mark Minchinton,

Natasha Herbert, Still Angela

photo Jeff Busby

Lucy Taylor, Margaret Mills, Mark Minchinton,

Natasha Herbert, Still Angela

A loose cluster of plays constellate, unikely companions, strange planets, sharing the unreliable gravity of Time in fantasias of recollection and projection. It’s a sometimes unnerving journey from theatre to theatre. It’s a long moment, lasting weeks, when synchronicity rules, déjà vu spooks and what makes immediate sense is later often inexplicable. Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen and William Shakespeare’s Macbeth at Sydney Theatre Company, Sam Sejavka’s In Angel Gear at The New Theatre, Alma de Groen’s Wicked Sisters for the Griffin Theatre Company and Jenny Kemp’s Still Angela for Playbox flicker and flare.

Frayn’s Copenhagen is performed on a planet. It’s Earth as an abstracted floor map pierced by a long wedge, on which physicists Bohr and the Nazi Heisenberg (and Bohr’s wife as accuser and commentator) create versions of their 1941 meeting and its abrupt ending, some predictable, one at least horrific. In this moral kaleidoscope, coherent purpose (why was Heisenberg there, to see a friend, to spy, to steal a secret that could make Germany a nuclear bomb, to compromise the Jewish Bohr?) evaporates into indeterminacy. Frayn boldly makes Heisenberg the self-interrogator, the primary constructor of the narrative, an act the playwright’s detractors have deplored (one going so far as to compare him with David Irving), but which makes this little journey into the heart, or rather the consciousness, of darkness, almost the nightmare it yearns to be. Copenhagen unsettles but finally fails me with is its inexorable neatness, from its pedestrian opening on through its ordered reconstructions and potted explanations of theories and the analogizing of these (like Heisenberg’s indeterminacy) with human psychology. The rationalist framework keeps us cosy, thoughtful, judges and jurors in a high-modernist in-the-round courtroom of Michael Blakemore’s direction and Peter J Davison’s design. There are moments when the temporal gears shift (however doggedly signalled by text and blocking) and the brain speeds up, attentive, accommodating another account that is like the one before, but then nothing like it. But Copenhagen stays strictly in the sphere of assaying moral relativism before driving its message home with a piece of perfectly executed stage spectacle. I left the theatre longing for the delirium of Polish cyberneticist and sci-fi writer Stanislav Lem’s chilling transformations of theories into projected realities in the novel Solaris and some hilarious short fictions where people bump into themselves with nasty consequences. Frayn’s Heisenberg never meets himself. I’d have to wait for Jenny Kemp’s Still Angela before I’d experience time and character illuminatingly out of joint. Nonetheless it was good to take the trip to Copenhagen, a serious talking head play which has generated debate and spinoffs that constellate around the play as it’s performed across the world, including Frayn’s elaborate updates in the printed program, The New York Review of Books (March 28) and a small companion volume, where he matches up his projections with the facts about an event almost lost to history as they begrudgingly emerge.

Macbeth is a butchering torturer, already a thug before the witches channel their prophecies of kingship through whoever happens to be available. Lady Macbeth is a trashy version of Anita Ekberg in La Dolce Vita, all brazen carnality but already quaking at her ambition for her husband. Duncan is a dwarf with a dancing lilt, sparkling like a faery king, too beautiful for murder. But the tale must be told, and it is with relentless determination, staccato delivery and rich and often bizarre imagery, some of it insightful, some of it silly (like the large, black, hairy muppet that rises from between the possessed Lady Macbeth’s thighs, bares its fangs and waves its long tongue at us). Instead of waiting for time to take its course and the witches’ prophecies to come true, Macbeth and wife take time into their own hands and push it fatefully along. Benjamin Winspear’s production works on and off, but it does remind us that Macbeth is no great intellect, that his wavering and his wrestling with superstition make him a creature of the moment, essentially blind to the future, and almost incapable of reflection. Russell Kiefel’s account of “Tomorrow, tomorrow and tomorrow…” therefore is bitter, impatient, not tragic. This is a man whose cure for his ailing wife is a lobotomy he performs himself. Macbeth is a killer from beginning to end; the verities of psychological development and character-as-time (one of Shakespeare’s inventions perhaps) are put to the test. Easy to dismiss, because it’s not the Macbeth we think we know, but the production conjures a frightening, claustrophobic timelessness that tyranny loves and that stays in the psyche for weeks to come.

It’s a short step from Macbeth to the subjects of Sam Sejavka’s In Angel Gear, junkies locked in the monstrous loop of addiction, in which time is either momentarily and ecstatically overcome or suffered as purgatory until the next hit. There’s little sense of the past and fantasies about the future remain just that. The play shows its age with creaky voice-overs that illustrate something of each of the characters in turn and there’s some awkward plotting, but the everydayness of the addict’s life with its narrow yearnings, squalor, glimpses of escape, criminal desperation, betrayal and easy violence are portrayed in both writing and production with an unequalled frankness for the stage and with the necessary sense of duration. The horror of time passing possesses these wracked bodies and restless psyches (fine, exacting performances from Winston Cooper, Jaro Murany and Victoria Thaine) as Sejavka and director Alice Livingstone allow the lived moment to unfold until you think you feel it in your own body.

Three sisters gather and reflect on the dead husband of one of them and on each of their thwarted lives. Secrets are revealed, darker and darker. Here was a man who screwed everyone sexually and emotionally, and a fourth woman professionally by stealing her research. He created a computer program, based on her ideas, that generates evolving ‘life’ forms. His womb envy lives on and he still dominates the lives of these women. The computer sits in a perspex swathed column in the wife’s home, university-controlled, humming, squealing if touched. In the Dead Husband genre (that includes Hannie Rayson’s Life After George and Tobsha Learner’s The Glass Mermaid) the challenge is partly to make the man intelligible, to understand how he could have had the impact he did, why this wholesale female surrender. Otherwise he remains a phallic archetype from a crude kind of feminism. Seeing the outcomes of his impact is to have only half the picture and that’s all we get in Wicked Sisters, a kind of verbal farce that edges towards Ab Fab but with heavy-handed playing, tiresome quipping and loaded plotting. Neither director (Kate Gaul, far better on more idiosyncratic projects) nor writer (Alma de Groen) are at their best and time stands still for all the wrong reasons as the characters rummage through each others’ lives. Only Judi Farr as the husband-murderer is allowed any gravitas, conveying a sense of weary, wounded interiority and a life where time is suspended, finished despite the revelations and the blackmailing that batter her.

In dark stillness, tall columns of moon-ish light slowly illuminate 3 seated Angelas (Lucy Taylor late 20s, Natasha Herbert early 30s, Margaret Mills 40 years old) in Jenny Kemp’s Still Angela. There are no explanations, these women and, soon the child Angela, simply co-exist in a shifting space of recollection and reverie across time. We enter of web of associations and resonances built out of things, animals, insects—lino, chess, horses, a spider, a bat—that like the women overlap and interweave. We hear the sound of a horse, a horse is spoken of, Angela calls the chess knight a horse. Lino, the backyard path, the chess board merge (“The truth of the matter is that there are always two landscapes, Viriginia. One always on top of the other.”) Angela 1’s scenes with husband Jack, little, spare naturalistic moments of out of sync emotion and sexuality, recur with Angela 2, same but different, quietly desperate—Angela: “You’re unconscious.” Jack: “We’re all unconscious.” There are 2 train trips to central Australia (narrow, several metre tall projections of the landscape rolling magically by), opening up not the landscape but the interior Angela—backyard and desert merge in the father’s making of a path like a chess board, the child is there, and her dead mother.

This simultaneity of actions and chronologies seems anchored in Angela 3, as if hers is the central consciousness, hers the challenge, speaking of herselves in first and third person: “There was something to discover about time, it was as if the sandwich, the bushes, the trees, the earth, were all getting on with something and she just wasn’t quite getting it. Something important was eluding her.” Perhaps it’s about being 40, feeling unconnected, living with the discontinuous narrative of past selves. As Angela 2 muses: “Am I six forever? Six in my thirty-third year?…27 years on a garden path?” The child Angela (dancer Ros Warby appearing tiny, marvellously angular, wrought, dropping…) evokes the mystery of a past almost too long ago to be understood except as play, watching and visceral anxiety. Perhaps it’s about a dead/lost husband. We don’t see Angela 3 with Jack (“I can’t hear you Jack you don’t have any sound, any presence, as if you were creeping along the pavement with bare feet, trying to trick me”). When asked “What’s wrong” at the play’s end, Angela 3 replies, “Probably grief.” But that’s all, because anything more literal would belie the larger forces at work in Angela’s psyche.

The return journey on the train from the desert unites the 3 Angelas in hilarious chat interspersed with glimpses of new strength. Angela 1: “Inside my clothes I’m an animal. Head neck sinews, lungs breathing, heart pumping. No one knows that between me and my dress, is a cosmic leap. A leap of faith into oblivion.” Angela 2: “His body hung in space like sexual atmosphere, you couldn’t help ingest him and even if his mind was elsewhere, he knew he was disappearing down your gullet and up your cunt!” Man: “And who was he?” Angela 1: “He was the Animus!” Still Angela is a liberating experience that realizes in performance the strange intersecting relativities of time, space and personality, theatre as dream. Jacqueline Everitt’s design, with its eerily inverted bushscape and startling depth of field, David Murray’s play with darkness and starry desert nights, Ben Speth’s film, and Elizabeth Drake’s nuanced score (horse, trains, distant songs, sometimes as if half heard, fragments from a dream) all merge with Kemp’s marvellous writing and the company’s deft delivery and fine movement (Helen Herbertson) yield an intensively subjective experience. A true play with time.

Time stands still. The recent death of Ruth Cracknell has deprived us of a great Australian actor. I treasure above all the memory of her rivetting performance in Beckett’s Happy Days. It’s as if I saw it only yesterday.

Michael Frayn Copenhagen, Wharf 1, Sydney Theatre Company, opened May 8; William Shakespeare Macbeth, Wharf 2, Sydney Theatre Company, opened May 11; Sam Sejavka, In Angel Gear, The New Theatre, Sydney May 3-June 1; Alma de Groen, Wicked Sisters, Griffin Theatre Company, The Stables, Sydney, April 11-May 4; Jenny Kemp, Still Angela, Playbox, Malthouse, Melbourne, opened April 10.

RealTime issue #49 June-July 2002 pg. 28