The uncanny in the gallery

Keith Gallasch, Mari Velonaki, Simon Ingram, Petra Gemeinboeck & Rob Saunders, Artspace

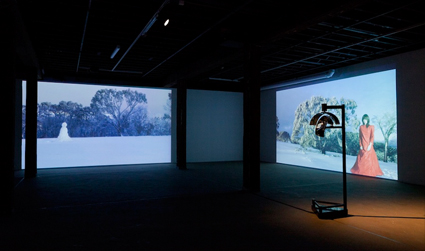

The Woman and the Snowman, 2013, installation view, Artspace Sydney

photo Silversalt Photography

The Woman and the Snowman, 2013, installation view, Artspace Sydney

“The uncanny valley is a hypothesis in the field of human aesthetics which holds that when human features look and move almost, but not perfectly, like natural human beings, it causes a response of revulsion among human observers. Examples can be found in the fields of robotics and computer animation. The ‘valley’ refers to the dip in a graph of the comfort level of humans as subjects move towards a healthy, natural human likeness described in a function.” Wikipedia

At Artspace three works engage with robotics in very different, bemusing and emotionally confusing ways. The ‘uncanny valley’ effect is most obviously suggested by and felt in Mari Velonaki’s The Woman and The Snowman. Petra Gemeinboeck and Rob Saunders Accomplice is even stranger—its robots, hammering at walls, with no suggestion of human appearance but a nonetheless palpable presence. Simon Ingram’s Smoking Bolts, its robots creating three large abstract paintings, is less spooky but mysterious in terms of agency: who and where is the artist?

Mari Velonaki, The Woman and The Snowman

In Mari Velonaki’s The Woman and The Snowman the resemblance between an onscreen robot and a female human is vaguely disturbing, but moreso when I learn that it is the creation of the advanced humanoid robotic research of Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro in Osaka and not the result of movie-making animatronics. The robot’s slight tilt forward and slow hand movements suggest mannequin-ish awkwardness but we know there’s more to ‘her’ than that.

On a large screen The Woman stands on a snowy landscape; on another, in the distance, is The Snowman, a conventional head and body minus limbs. The trees behind suggest Australian mountain country. Forward of the angled screens is an enigmatic device of human height and comprising two gleaming, rotating chrome shells arcing around a small video monitor moving on its own trajectory. Alpine countryside, a large house and pine forests appear on the screen, reflecting the artist’s Swiss origins. Amid these images another appears in which a party of well-dressed people (styling suggests mid-20th century) have raised their glasses in celebration of, perhaps, the skiing season. The still image has been carefully [re-]constructed with a 3D depth of field and a tracking shot that make its subjects seem faintly robotic—a sensation sometimes felt when looking at old carefully composed photographs. The looping dance of the kinetic machine and its self-contained imagery evokes a sense of both the intimacy and artificiality of capturing personal memories, especially when juxtaposed with The Woman who in an imminent future might enjoy some skiing and build a snowman.

The combination of Australian and European landscapes, of Swiss human and Japanese humanoid forms is underlined by the pleasant entwining of Western and Japanese musical forms for strings, compensating somewhat for the snowy coldness of the large screen images and The Woman’s inertia, as does the kinetic machine which looks like it might have come from a luxury furnishing store.

Petra Gemeinboeck and Rob Saunders, Accomplice

Accomplice, 2013, detail, Petra Gemeinboeck & Rob Saunders, Artspace Sydney

photo Silversalt Photography

Accomplice, 2013, detail, Petra Gemeinboeck & Rob Saunders, Artspace Sydney

The score for The Woman and The Snowman is punctuated by the occasional sound of Ingram’s robots dipping their brushes into paint trays and buzzing to the canvas, but more so by the pounding heard from Petra Gemeinboeck and Rob Saunders’ Accomplice. At least two things make this a profoundly disturbing if witty work. The first is the evocation of images reminiscent of, among others, paranoid schizophrenia symptoms portrayed in Daniel Paul Schreiber’s autobiographical Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1903) and Roman Polanksi’s film Repulsion (1965) in which imagined forces break through walls. At work behind installed walls in the gallery, the robots in Accomplice hammer away at varying durations and with apparently different intensities—doubtless amplified by how far they have worked their way into the wall and also where they are pounding. This sonic detail yields a sense of insistence and multiplicity. Suddenly only one robot is to be heard; then, three at once, each with their own percussive identity. The sense of impending, slow invasion is palpable, especially when a small rectangle of the wall falls onto the rubble-strewn floor.

It’s intriguing that robots don’t work at one spot until finishing their task. They stop, glide away and commence work on a new spot or one already commenced. We glimpse them through the holes they’ve created, gliding up or down or horizontally, illuminating their way with ringed ‘eyes’ of intense blue light, swivelling as if inspecting their work…or us. The effect is as comical as it is anxiety-inducing, the latter state increasing when we learn that “[e]ach robot is equipped with a motorised punch, a camera, and a microphone to assist in the complete transformation of the surrounding environment. Collectively, these robots explore, learn, play and conspire by knocking against the wall, producing holes and patterns that mark the evolution of their social development” (room note).

Just how autonomous this robot clan is, in terms of artificial intelligence and agency, is an issue underlined by the work’s title: Accomplice. Who is the accomplice? The robot clan, empowered intellectually and mechanically to destroy a room for an artist to make a point about the power of robotics? Or the artist, who having created the clan loses all but the fundamental agency to ensure destruction, which the robots execute on their own terms? Clearly, autonomy of the human variety is a long way off for these machines, but if they are in fact learning and planning then the future inches nearer. We grow more and more excited at our capacity to create intelligences other than our own (if for the moment modelled on ours) and just as apprehensive about things that hammer inexorably through the walls of our wellbeing.

Simon Ingram, Smoking Bolts

Smoking Bolts, Simon Ingram, installation view week 3, Artspace Sydney

photo Silversalt Photography

Smoking Bolts, Simon Ingram, installation view week 3, Artspace Sydney

Placed flush to each of three large canvases are pairs of vertical bars. On each pair sits a small robot with a paint tray and a shaving-brush-like brush. The robots move up and down and the bars horizontally. A third design factor, room for the robot to angle itself across the bars, allows it to paint more than vertical and horizontal lines. A blue painting, almost totally filled in with a huge blue, densely painted circle, still reveals bare spaces in which earlier rectangles and diagonals are evident.

Agency in Smoking Bolts we are told is human: “These painting robots are operated remotely by the artist in New Zealand and by Artspace staff to enact a trans-Tasman painting collaboration that reframes painting’s traditional mode of production” (room note). Just how that agency is shared is not evident. A laptop computer sitting by one of the paintings-in-progress reveals a diagram of a large circle and triangle, evident too on the canvas, and suggesting pre-planning. But much else has happened—a swathe of lines straight up and across—with the robot still working doggedly on a red vertical to the one side as we watch. So, while it’s clear, one way or another, that humans are at work here, there is a sense of absence, of the artist working surreptitiously, which the room note curiously aligns with stealing: “the title of the exhibition is derived from the culture of the heist, or break-in, where something valuable is snatched leaving nothing behind but the smoking bolts.” Just what has been snatched—an audience’s desire to identify with an artist and not a machine?

Enculturing robots

In live art and new game theatre theatre (see RT115) there is an increasing trend towards artists making works for their audiences to perform. An audience is inducted—learns the rules—but also brings issues and narratives to a game. It is programmed but will take the game wherever it goes. The game persists, but outcomes will never be the same. Simon Ingram hands over hands-on creation to robots who wield brushes in his stead; and he shares agency over these machines with others—the Artspace staff. Petra Gemeinboeck and Rob Saunders nurture the intelligence of their robots, allowing them to learn and collaborate within the artists’ framework, and again with uncertain outcomes as to precisely how these machines will destroy the walls.

Robotic agency does not appear to be an issue in Mari Velonaki’s The Woman and The Snowman—a work about how we see both ourselves and ‘them.’ She illustrates the complexities of the meanings and associations that constellate around robotics in terms of memory, prediction and anthropomorphism. From snowmen to robots, humans like to make things in their own form, as many believe the gods first made us. We have long imbued inert things with imagined life and fantasised living machines. Now that they are showing signs of life, this intriguing and thoughtful Artspace exhibition proposes and enacts the enculturation of and collaboration with robots. Uncanny.