The struggle for cineliteracy

Jane Mills

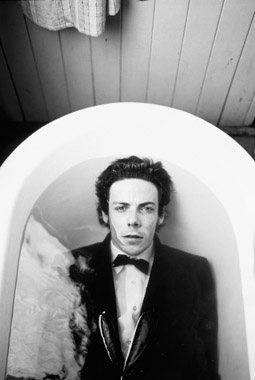

The Goddess of 1967

The annual Emirates AFI Awards play a crucial role in protecting the health of our screen culture. They give us the chance to ask what Australian cinema is and what we’d like it to be. This isn’t such a solipsistic or negative activity as it sounds.

It lets us see more clearly that Australian cinema is, as Tom O’Regan clearly demonstrates in Australian National Cinema (Routledge, 1996), “a messy affair…not only in our ways of knowing, reading, consuming and producing films and the larger film-making milieu of which they are a part, but also a messiness among the films themselves with features far apart” in terms of style, content and purpose. It’s also in constant conversation with the mainstream and other national and local cinemas. If it weren’t, our whole culture would be in trouble since our cinema plays a large part in how we imagine ourselves in relation to the rest of the world.

Our cinema shows how our filmmakers are negotiating and participating in an ever-moving dialogue; what critics, reviewers and audiences watch, write and think about is also in constant motion. What we want our cinema to be is never static: if we don’t speak out about what we want and don’t want Australian cinema to be, then the dynamic relationship between film producer and consumer becomes arid and nothing, or very little, can come to fruition.

For some years, a number of film critics have expressed concern about the way our production and critical practices have come to a halt due to a lack in awareness and understanding of screen culture. That audiences lack this is understandable: despite the valiant efforts of SBS and the AFI, the burgeoning number of film festivals, and the tiny number of brave independent cinemas and distributors, there simply isn’t the opportunity for audiences to see a wide range of movies from local and national cinemas all over the world. That filmmakers also lack much knowledge of the many different ways cinema can tell a story is reprehensible, although the responsibility may not lie entirely with them: they too have to be taught and our film schools and university film courses may not be adequate to the task.

In the late 1980s, Elizabeth Jacka wrote of “a loss of vision, a failure of nerve” in Australian cinema and regretted “that the complex set of discourses and institutions that constitute the space in which cinema exists is deeply inimical to ideas, controversy or aesthetic adventurousness” (“Australian cinema: an anachronism in the 1980s?” in S Dermody and E Jacka eds, The Imaginary Industry, Sydney, Currency Press, 1988). In the mid-90s O’Regan expressed similar concern about a cinema that has a limited range of “film-making repertoires” and much still to embrace and understand. Presciently, Adrian Martin had diagnosed the causes in the 80s:

[E]very practicing film-maker must ask…‘What is cinema for me?’ […must] be able to dream or imagine the cinema that he or she desires. I tend to believe that, for true film-makers…this imagining is not primarily expressed in terms of, ‘What do I want to say with film?’ but, rather, ‘What do I want to see and hear on film?’ That is, the ability to imagine certain configurations of image, sound, movement, form, fiction and mood matters more than convictions concerning which social issues, types of behaviour and so on should be presented on screen. Perhaps for true filmmakers the two stages happen simultaneously: for to imagine a form of cinema is naturally to project certain images and shapesof life in action.

“Nurturing the Next Wave: What is cinema?” in Scott Murray (ed) Back of Beyond: Discovering Australian Film and Television, Sydney, AFC, 1988

The analyses of last year’s AFI nominations suggested that few of our filmmakers had a strong grasp of film language. Tina Kaufman, warning of the dangers of neglecting screen culture, concluded: “If the films produced in a year are the outward manifestation of the health of the local industry, the Australian film industry is indeed ailing. (Metro, 121/122, 2000). Given this persistent critical framing of the question ‘What is Australian cinema?’ and the apparent refusal of filmmakers to ask the same question, how do this year’s movies measure up?

He Died With a Felafel in his Hand

There’s certainly been diversity. I feasted my eyes on the spectacular Moulin Rouge (Baz Luhrmann), but felt visually starved during the stage-bound Silent Partner (Alkinos Tsilimidos), which looks more like a lump of yesterday’s porridge than a movie. I was forced to play anthropologist to Australian culture, as O’Regan puts it, in films such as The Dish (Rob Sitch) and La Spagnola (Steve Jacobs) and also, more reluctantly, to nerdy, forever-adolescent, male culture in He Died with a Felafel in His Hand (Richard Lowenstein) and Mullet (David Caesar). But, if these irritated me witless, I was deeply moved watching the men in Ray Lawrence’s thoughtful Lantana learning either to grow up or that they never will. And, at the time, I didn’t even notice how the female roles were mostly reduced to mere cipher in the gripping thriller The Bank (Robert Connolly).

Watching Serenades (Mojgan Khadem) and Yolngu Boy (Stephen Johnson) I sadly agreed with Adrian Martin’s 1988 dictum: that a cinema of good intentions, which prides itself on its progressivist record, is essentially a conservative cinema. But an antidote to androcentricity and the mainstream, at least, was to be found in the otherwise disappointing The Monkey’s Mask (Samantha Lang) and in Clara Law’s wild and unwieldy The Goddess of 1967.

While critical of many of these films, I also enjoyed several and—as I increasingly demand of a movie—I got to see and/or hear something entirely new or to detect a cineliteracy behind the filmmakers’ repertoire of screen language. This year, 4 films filled this need—that’s a lot in one year. First-time director Connolly (The Bank) drew upon an extensive knowledge and a keenly intelligent understanding of film language and history that makes me impatient for his next film. The more experienced Lawrence clearly has a similar relationship to film culture and he uses it to pleasurably unsettling effect in Lantana.

Law’s The Goddess of 1967 delivered a more dilute pleasure. There have been few Australian arthouse features in recent years—I can’t think of one since Tracey Moffat’s beDevil (1993)—so it was especially important that this film was funded and distributed. At times, just when the plot or dialogue made it irredeemably banal, Law and her cinematographer, Dion Beebe, gave me a visually exciting and a startlingly different cinematic experience that engulfed me in wonder.

Finally, Moulin Rouge. I may not be ready to give a considered criticism of this film, as my love for it is still pretty much unconditional. Like the cancan dance itself, it flirted and seduced by frustrating my desire for a full look at what I know to be there, but which can’t be revealed if I am to be kept wanting more. I saw this film in Dubbo in rural New South Wales at a late night screening. Whatever the cultural differences in the audience, well after midnight we all gave the film a standing ovation. Now that was something entirely new.

In order to draw upon the full palettte of options that a knowledge of screen language offers, a filmmaker needs to be aware of the cinephiliac and how to deliver it. Too often, Australian filmmakers appear to be unaware of this.

Acutely aware of the need for screen culture if Australian cinema is to flourish, the AFI discovered a way of delivering it. This explains why, last June, I found myself bathed in sweat in the large, galvanised iron barn-cum-studio of Broome’s Indigenous radio and television station under a 20 foot papier maché rainbow serpent, giving a critical analysis of the title sequence of Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969).

Exploring the meaning of the intensely cinephiliac moment when Captain America, aka Wyatt, aka Peter Bogdanovich, takes off his wrist watch, kisses it goodbye, and chucks it into the dust where it lies like the tin star in High Noon, a symbol of law and order that no longer works, is tough when you’re crying out for a long, cold drink and a swim, and Western Australia in 2001 seems a long way from late 60s Californian hippiedom.

But there was no stopping the group of cinephiles and would-be filmmakers attending my seminar; they were unfazed by the temperature in the high 30s, the almost deafening sound of the enormous 8 foot fan as, like a projector, it went wyrrrrum, wyrrrrum (or was it dziga, dziga?), and the impossibly fuzzy picture on a sand-blown monitor.

Moving on from Hopper’s dope-filled frames and a range of other classic road movies, from Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night to Ridley Scott’s Thelma & Louise, I analysed Australian cinema’s love of the genre, including The Back of Beyond (John Heyer), The FJ Holden (Michael Thornhill), Wrong Side of the Road (Ned Lander), Backroads, (Phil Noyce), Mad Max (George Miller), Priscilla Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliott), Bill Bennett’s Spider and Rose and Kiss or Kill and, finally, The Goddess of 1967. What did rural Australians make of this intensely intellectual, multicultural, postmodern road movie?

That they saw it at all was thanks to the AFI’s Burning Rubber initiative, which took a handful of Australian road movies—followed up by my 2-hour seminars—on the road to rural towns all round Australia to launch a road movie video-making competition. In Leongatha, Townsville, Bundaberg, Dubbo, Tamworth, Broome, Bunbury, Darwin, Port Lincoln and Launceston, while some said they were baffled by Clara Law’s film—they’d never seen anything like it—many told how deeply impressed they were, precisely because they had been unaware of cinema’s ability to speak in so many different tongues.

I’ve yet to see whether their own short road movies reflect an increased awareness of film history and culture. But I’m optimistic that they’ll prove a more thoughtful audience for Australian movies. In the long term, this might mean that there will be greater competition for an AFI award from filmmakers who ask the question ‘What is cinema to me?’ Those who do are more likely to make uninhibited films, displaying a greater range of “film-making repertoires” and more “ideas, controversy or aesthetic adventurousness” than many do currently.

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 15