the spiritual in the popular

Eleanor Brickhill finds unexpected depths in visiting US dance company Momix

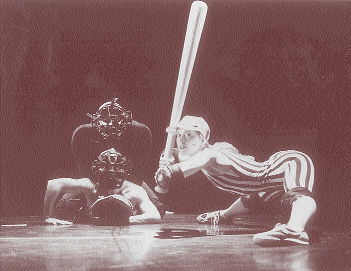

Momix, Baseball

photo Moses Pendleton

Momix, Baseball

At its best, there’s something attractive about American humour. In Baseball and Passion, two works by Moses Pendleton, performed by Momix, there are enough salient cues for events to coincide with personal biases, even if at first glance the images in the program act like warning signs. Clueless gum chewing ball players strike facile poses with bats. Perfectly linear, rigorously symmetrical groups of dancers threaten to paralyse the imagination. Nervousness overtook me until I read a quotation from Woody Allen, also included in the program, “I love baseball, you know it doesn’t have to mean anything, it’s just very beautiful to watch.” I was relieved with this more comfortably oblique perspective.

In both works there’s an unexpectedly rigorous interior texture, a tang of spirituality, a sacredness of sorts. Profuse images cluster, working to create dense, open-ended iconographic histories which speak about the dimensions of a tart spirit manifesting itself in the profane cultures of everyday human endeavour. Take an apparently sweepingly simple and familiar passion for a game of baseball, and if you care to follow this line of thinking, it turns out to be part of the same deep well from which spring other mystical and unfathomable aspects of human civilisation which follow us from the ancient into the contemporary world. In Passion, sexual fervour, death, struggle and ecstatic religious immolation are made of this same stuff.

An important feature of both works is the layering over live performance of projected slow fading images on a scrim which together capture expansive cosmological perspectives. In Baseball, we see ancient, ‘graven’ images and monuments like Stonehenge overlaying the vivid and live spirit of the pitch on stage; corpulent female Venus figures (described sometimes as homo sapiens’ first object of worship); bat and ball images, banal and serious, are conspicuously genital—a girl in a half-shell; a ball nestles egg-like in a baseball glove, simultaneously vulval and phallic. We see performers regress to a 2001 scene, exercising an atavistic pleasure in hitting soft squashy things with long hard things. We see emblematic crossed bats; Moses with his commandments, the set of rules for the game; film star images, Humphrey Bogart, Babe Ruth; American Indian warrior images; beer-can culture; the Stars and Stripes Forever; a dance within pliable and perfectly balanced double arches set to Arvo Pärt’s Stabat Mater (Stood the Mother, full of grief), and militaristic synchronised bat play. One woman’s Sufi-like spinning solo is able, with immaculate simplicity, to draw us into an understanding of that peculiar kind of devotion.

Nations develop civil religions whose liturgy and iconography are capable of sustaining a range of meanings for devotees, because the symbolism, though intensely religious, is not from any orthodox faith, but typically taps primal or ancient sources. Moses Pendleton’s Baseball shows us all the hallmarks. Civil religion in the US is grounded in the Constitution, directed at binding the individual to the state, “One nation under god”. Virtues are civil ones: physical strength, skill, team spirit. No religious spirit celebrates any God Out There, but exultant humanity right here in the world of competition, politics, finance, dirt, fame, greed, sex, beauty, pain, and skill, and the damp meditative autumnal (should that be fall) afternoons spent tossing a ball around in the wet leaves. This, an insipid but perfect closing image of Baseball, brings that spirit home, binding it to a place which is fundamentally American, even in its own self-mockery.

The immediately spiritual images of Passion take us unhesitatingly to Shiva, Indian god of the universe and lord of the dance, a huge branching tree, the teeming ardent struggle of organic life, the passionate attachment of nerve and cell, fierce, microcosmic vortex of pistil and stamen, flower and insect, vultures in a dead tree, ginseng root—a human image—folds of cerebral cortex, decomposing flesh, war, medieval images of flagellation and ecstasy, monastic penance, repetitive, extreme and peculiar. The passion of a bride, whether of Christ or man, comes to us bare breasted, swathed in tulle. There is a profound eroticism in all of this, from the images of Italian renaissance women, tiny winged cupids with dimpled legs, to the huge mechanical clock marking the passage of both cyclic and linear time.

Neither frail, brittle nor pre-pubescent, the women’s bodies have a more flagrant aesthetic independence not so familiar to Australian mainstream dance. An apparent maturity and succulence seems to walk all over quaint narrow female images we have unfortunately come to expect, and embarrassingly, to think of as erotic. These dancers show no signs of physical struggle, they make no slips, they have immense facility, they are perfectly attuned. Meanwhile, the choreographic designs are surprisingly so foursquare, repetitive, turn-taking, linear, and peculiarly literal as to make me wonder why their dimensions do not feel more circumscribed. Such are the illusions, farcical and sophisticated, which are created with meticulous precision. You need a soft focus on these images for them to do their work.

Momix (U.S.), Baseball and Passion, conceived and directed by Moses Pendleton, Sydney Dance Company, Sydney Opera House, May 2-9.

RealTime issue #13 June-July 1996 pg. 36