the rise of the superdoc

george gittoes tells all to catherine gough-brady

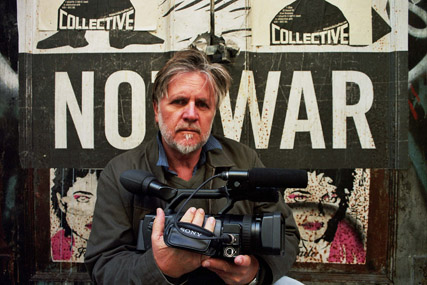

George Gittoes

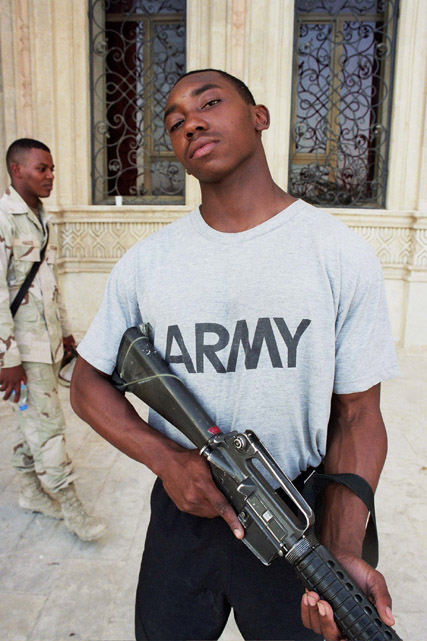

AFTER A 20 YEAR BREAK FROM DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKING, THE VISUAL ARTIST GEORGE GITTOES RETURNED TO THE FORM IN 2004 WHEN HE RELEASED THE SELF-FUNDED SOUNDTRACK TO WAR—A FILM IN WHICH WE ALL LEARNT THAT TANKS AREN’T JUST KILLING MACHINES, THEY’RE DEADLY STEREO SYSTEMS. NOW, IN RAMPAGE, HE’S VENTURED INTO A TOUGH MIAMI ‘HOOD IN A HIP HOP DOCUMENTARY WITH APPEARANCES BY SWIZZ BEATZ, FAT JOE AND DJ KALEB.

Gittoes returned to documentary because of the digital camera. The price of shooting dropped dramatically and the amount of equipment to be carried diminished. Gittoes says, “Now I can shoot a film and it can be in a cinema, but it is not unlike doing a painting or a drawing. I can do it pretty well by myself.” Gittoes is a real life example of the technological revolution many anticipated in the mid 90s. He’s also a fervent promoter of the notion of the ‘superdoc’—“a doc that has pushed up the values so it can work for people going out to the cinema—like a feature film does.” Gittoes described the job of a superdoc director as the same as the job of a feature film director: “you have to get the best performances out of people. You haven’t got actors so you’ve got to create situations where people transcend and actually lose their inhibitedness and they’re caught up in a moment. They are absolutely real, they’re not doing some pre-thought out speech.”

Gittoes gave an example of this from Rampage: “I went and interviewed Joe Byrne in his office. Most documentary filmmakers would be happy with that because he is an expert in terrorism as well as having been a cop in Brown Sub [a Miama ghetto, home of the film’s main subjects, Elliot and Marcus.] As someone making a superdoc I knew that that was boring. Basically you can’t be boring.

“So, Byrne had not been back to Brown Sub for years. I was aware that he wouldn’t know how dangerous it was. So I organised for him to meet me there, he had an inkling of it because he brought his gun. And Elliot didn’t want to go back there because his brother had been killed there. The gang was threatening to kill Elliot and me and all of us. So we get this very very tense dramatic scene where the people who killed Marcus are actually circling us. And in the back of my mind the clock’s ticking and I’m thinking how many more minutes have I got to shoot before we get shot. That is superdoc making.

Rampage

“Because of that tension, Elliot doesn’t talk to the camera as a talking head, he is angry with me and he talks right through the camera. He virtually abuses me, he says, ‘How would you feel coming back to the place where your brother was killed? What if someone close to you was killed?’ Joe Byrne, the tough old cop who has seen a lot of homicides, says, ‘Yeah we’d better get out of here.’

“That’s the difference between your ABC commissioning editor-type documentary, where the talking head expert does their boring thing across a desk, and a film that’s actually got the values of drama.”

Gittoes thinks that television commissioning has a detrimental effect on the art of documentary filmmaking: “I’m a ‘fine artist.’ Soundtrack to War [2004] is being shown in the Museum of Modern Art, in ACMI here in Melbourne as art. It is art. Documentary up until the superdoc was applied art and it will always remain applied art if insecure documentary makers have to go and get presales and work through the guardians of the gate, the, what’s his name, Stuart Menzies and Dasha Rosses and Jennifer Crones—these people who play Medici with public money, who want to take control. Documentary film is a collaborative thing but ultimately it has to be a single vision, like a work of art—like a Kubrick or Scorsese film. And yet it is being turned into an applied art.”

Gittoes had investment from the FFC for post production on Rampage and spoke about the effect that this had on him and the film: “One of the suggestions of the FFC was that we cut out South Beach, and lose the Australian section of the film. And I disagreed with that and I had sleepless nights over what they were going to do to me. Without [Australia’s] South Beach I don’t think that there is any comparison [with the poverty of Brown Sub]. Ultimately it’s all on the director and the buck stops with the director even though these bureaucrats want to control documentaries. They can just refuse to give us money next time if the film bombs at the box office.”

When Gittoes talked about other films he considered to be superdocs he mentioned Bowling for Columbine: “One of the big elements was the fact that Michael Moore acts as a bridge between being the viewer and the subject of the film. Now with Rampage, frankly, there might be politically correct people who would say that if it was a pure documentary that I should not be in it. I don’t know where they get that from. They’d be happy for Attenborough to be walking around with the elephants. Those people would probably find that there are dozens of rap films that they’d never watch, which I have watched, which are inaccessible because they don’t have a character like me. There’s a tremendous precedent for Rampage which is Nick Broomfield’s film Biggie and Tupac, where Nick’s getting around with his little bum bag and his microphone and he’s from another culture, like I am. Of all the films I’ve seen on Tupac, that’s the one that works the best.”

In the end though, Gittoes says, “Really, the only rule with a superdoc is that it has to work. And you only know if it works if some cinema chain is prepared to put it on against dramas. Rampage is getting more exposure in more cinemas than any drama recently made in Australia. It’s getting more cinemas than a film like Candy which has got all the big actors and producers.”

Rampage, director-producer George Gittoes; playing in Australian and London cinemas and in festivals in Copenhagen, Stockholm and New York. www.rampagethemovie.com. Distribution: Madman, www.madman.com.au

RealTime issue #76 Dec-Jan 2006 pg. 18