the quiet influence of accrued wisdom

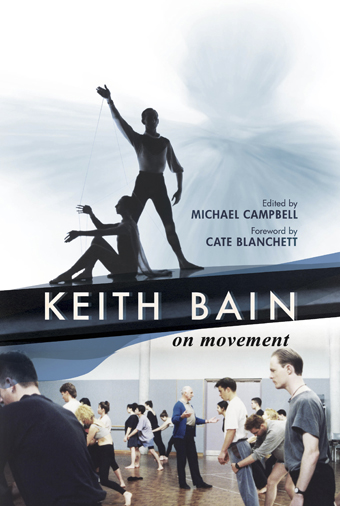

jeremy eccles: keith bain on movement, currency house

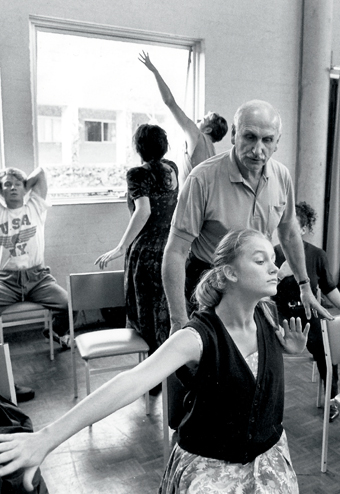

Keith Bain teaching at NIDA Open Day July 1993. Sophie Heathcote in the foreground (NIDA Archive)

$64.95 MIGHT SEEM A LOT TO PAY FOR A 320 PAGE BOOK THAT’S ABOUT TEACHING A MINOR PART OF AN ACTOR’S CRAFT—AN ILLUSION NOT HELPED BY A MUNDANE CLASS PHOTO OF KEITH BAIN DOING JUST THAT AT NIDA ON ITS FRONT COVER. BUT THAT WOULD BE TO WILDLY UNDERVALUE THIS BOOK’S CONTENT. FOR WHAT EMERGES IS THE REVELATION THAT MOVEMENT IS ABSOLUTELY CENTRAL TO THE ACTOR’S ART; AND THAT THE NOW 84 YEAR OLD KEITH BAIN WAS ABSOLUTELY CENTRAL TO THE DISCOVERY OF THIS IN AUSTRALIA.

Indeed, one might argue that our justifiable reputation for ‘physical theatre’ would never have developed if Doris Fitton had not summoned Bain to her Independent Theatre in 1959 and commanded him to begin a movement class. At that time, neither Bain nor the imperious Fitton had any idea what he was going to teach. What’s more, Melbourne’s APG claque would certainly disagree with Bain’s (and NIDA’s) centrality in all this! But Bain was there when Reg Livermore pioneered his first solo in 1961, when John Bell needed him for The Legend of King O’Malley in 1970 and when Jim Sharman tackled Jesus Christ Superstar in 1971.

The claim is further justified by the wide range of adoration offered by Bain’s former students in the book—ranging in time from Reg Livermore to Matthew Whittet, and in their influence on the national scene from directors John Bell, Jim Sharman, Rex Cramphorn, Gale Edwards, Moffatt Oxenbould and Baz Luhrmann to actors on the world stage such as Mel Gibson, Geoffrey Rush, Hugo Weaving and Cate Blanchett.

Do we believe the hyperbolic Blanchett when she declares in her introduction to the book that “His teachings are the foundation of my technique”? And “Keith Bain was and is the biggest single influence on my work as an actor”! It only adds up when her scattered quotes are brought together to include this: “He would brook no laziness, but would support your failure, because in this failure he could sense advancement round the corner; the attempt at what was currently impossible.”

The key to that achievement, of course, was that Bain was a brilliant teacher per se—and his thoughts on that subject should find a ready audience amongst teachers everywhere. Geoffrey Rush brackets him in pedagogy with Parisian clown-master Jacques Lecoq in their ability to “plant some personal awareness of what the parameters of creativity might potentially become in you.” This is despite Bain’s unvarnished description of the young Rush as “the most awkward looking, gangly, pimply student with the strangest physicality that you ever saw—and a power of concentration you wouldn’t believe.”

Bain had become a school teacher in emulation of the glamour he associated with the pre-WWII arrival of such authority figures in a remote town like Wauchope—where am-drams (amateur dramatics) and ballroom dancing were the major forms of relief from simply surviving the Depression. Fortunately, he was lead astray from this noble career when, at 27, he decided to become a dancer—not just one sort, but a polymath developing his improvisatory skills under the tutelage of expatriate ‘modern’ dance sage Gertrude Bodenweiser while earning money on TV variety shows or down at the Trocadero Ballroom (revived this year by the Sydney Festival) where his craving for freedom of expression in the samba, paso doble and cha-cha lead to his becoming The Man who was Strictly Ballroom. For the dancer and teacher was also a dab hand at engaging his students at NIDA—including the young Baz Luhrmann—with a bit of old-fashioned, country yarn-spinning.

Keith Bain, On Movement

Indeed, the now white-haired Luhrmann declared at the book’s launch that Bain had taught him that learning was a life-long affair. Which makes it all the odder in the book that NIDA’s former bosses John Clark and Elizabeth Butcher fail to take the opportunity offered to explain why they backed both Movement and Bain by taking him on (part-time) in 1965. At least Katharine Brisbane—doyenne of Aussie theatre critics from 1967 until the 80s—used her current hat as publisher of the book to issue a mea culpa at its launch for never once crediting Keith’s contribution to the productions she was reviewing on stage. “We in the stalls knew nothing of his work.”

Bain himself is aware of this gap, using the book as an opportunity to remind directors that, as another former student, Miranda Otto, puts it so succinctly, “Movement goes on all the time”—not just when the text calls for a dance or a fight. Every entrance and exit has to look spontaneous, vital emotions have to find physical expression, and Movement can uncover deeper degrees of truth, subtlety and spectacle. Perhaps the most readable of the teaching chapters is that on Space—a philosophical disquisition as much as a textbook case. As NIDA staff member Kevin Jackson comments, “[Bain] introduced us to the notion of being a god, being truly alive in the magic space on-stage.”

As to Bain’s own skills at on-stage transformation, I can’t do better than quote actress Jeanette Cronin: “Those noble shoulders would collapse under the weight of indignity, that majestic chest would contract into a cave of sorrow, the proud neck could no longer support that once bright visage, the dancing eyes now drooped like raindrops. That wicked mouth lost its wit. He showed us a little finger could be sad; a mouth can contain the fury of a thousand frustrations.”

But then Keith Bain had experienced the “miracle of transformation” very early. It came “when I watched someone as grounded and normal as my barber father offer his hand to my mother and lead her on to the dance floor. Somehow, as if on a breath, their two bodies connected into one new unity as they moved into the figures of the dance.”

Amazingly, Bain also had time off-stage to be, in his own words, “a bloody busybody,” forming and chairing many of the major national and international dance bodies that now exist. But the book covers too little of the process whereby Keith brought together the warring tribes of dance through the simple expedient of a Dancers’ Picnic, quietly organised under the aegis of UNESCO’s International Dance Day. It has more noisily (but more narrowly) lead on to today’s National Dance Awards.

In the last issue of RealTime, Amanda Card reviewed Alan Brissenden and Keith Glennon’s Australia Dances (RT100), a book that had its genesis in the 1950s. Movement is obviously a stop/start matter. Bain began his book in 1993 when he received a Keating Fellowship for that purpose. The writing since has been by him while shaping of the book belatedly fell to the Keith Bain Book Team, notably his successors at NIDA, Julia Cotton and Anca Frankenhaeuser, under editor Michael Campbell. The beauty of this is that Keith Bain can use the word ‘luck’ a lot, while the beneficiaries of his belief in drawing “the best version of themselves” from so many students and casts can fall in behind Hugo Weaving and offer up their versions of Weaving’s, “He is a sort of guru to generations of us.”

Keith Bain on Movement, edited by Michael Campbell, Currency House, Sydney, 2010, hard cover, $64.95

RealTime issue #101 Feb-March 2011 pg. 40