the little match girl: safety first

andrew harper

The Little Match Girl

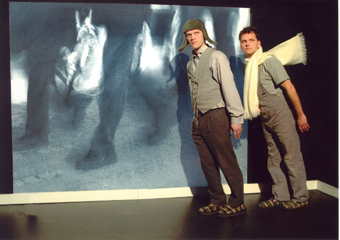

photo Jan Rüsz

The Little Match Girl

A strongly familiar story that deals with the cold and lonely death of an innocent girl might seem to be a strange choice for a piece of children’s theatre, but then again, perhaps discussing such a difficult topic is exactly what we need from theatre. It’s a brave thing to even attempt, so a great delight to experience something that must have been so difficult that achieves as much as Denmark’s Gruppe 38’s production of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl.

Children’s theatre has different concerns from its adult counterpart, and there’s a common assumption that the performance has to be responsible for the emotional wellbeing of the younger audience. Given that both story and outcome, are well known, the nature of this responsibility looms large, and the company’s reaction to this has shaped the nature of this production in quite particular ways. From beginning to end the cast are visible, and they acknowledge the audiences’ presence. The set, and general appearance of the performers has a hint of genteel poverty, which gives the whole thing a clownish, unthreatening quality. The performers use their own names, introduce themselves to the audience, have their roles explained and produce ‘scripts’, which are not scripts in the traditional sense but images. All perfectly elegant and deft deconstructive moments, and indeed there was much of this throughout the performance: a piece of paper being moved about with a long thin stick to create an illusion of wind is eventually grabbed, revealed as a long thin stick and not wind at all. It’s an illusion. It looks amazing but it’s not real. It’s just a story you’re watching: we’re reading it from scripts, using clever theatrical tricks; you can see us using them. It’s all right. It’s fine.

The set, stark and simple, utilizing projection in many ways, had one particular premise that fascinated – the performance took place within a smaller square on the stage, that was clearly defined early on as a dangerous place to be. Performers entered it at their own risk, a little nervous but with brave hearts. They would take whatever risk necessary for their story, unselfishly keeping the audience a little safer still.

It’s not always dangerous in the space however; a simple projection onto a shoulder-high silhouette of a four-storey townhouse is raised from the floor giving the performers a chance to create images of warmth and food and comfort. It’s all done with a small projector, visibly worked by the performers. It’s all an illusion; it’s not real. We are telling a story. This is how we are telling it, using these clever little things that are simple and easy to use. What’s extraordinary is how many of these things there are, and how much is evoked by their clever, economical usage.

I found this work extraordinarily satisfying. It was everything I look for in strong theatre – intelligent, even witty use of theatrical devices that do not overwhelm or cheapen the story and its attendant emotional resonances. The energy that was created, controlled and shared was very involving; I was caught up: charmed by the way the company told stories and moved by the story they told.