The colour of opera

Jonathan Marshall: Teorema, Chamber Made

Chamber Made Opera Company, Teorema

photo Ponch Hawkes

Chamber Made Opera Company, Teorema

Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1968 film of his own revolutionary, epic poem Teorema threatened to cast a deadening shadow across composer Giorgio Battistelli’s recent wordless opera. Rather than reinterpreting Pasolini or Battistelli, Chamber Made director Douglas Horton’s staging critiques them both. If Pasolini’s cinematic mise en scene is fractured, Horton’s is dispersive and mutually antagonistic.

There are parallels between the energies of the score, Pasolini’s critique of capitalist, bourgeois domesticity, the mute, hysterical witness of the Italian characters, and the return of primal practices and emotions. But Horton’s overall tendency is not so much to knit these themes together as to leave them free to act against each other; to juxtapose design elements (light, staging) with the dancing body (Michelle Heaven as the daughter), the acting body (Ian Scott as the father) and other intermediate techniques (dance-maker Shelley Lasica as the mother, theatre-maker Tom Wright as the son). If opera is the term for a work lacking singing, mime, or even formal dance, then this is anti-Wagnerian opera. It is not so much total theatre in the sense of a gigantic, musical-theatrical deus ex machina, as totally dysfunctional theatre.

This quality builds throughout the production, making the second half more sensational and melodramatic than the first. We move from a series of unnecessarily telegraphic, discrete seduction scenes, to a series of chaotic, overlapping aesthetic vignettes owing more to the infamous exhibition of British postmodernist installation and ‘shock-art’ Sensations, than theatre per se.

Behind opaque plastic curtains lives a well-to-do, classically European family (in whiteface even). The Stranger enters—black, male and muscled, an embodiment of exoticism within their home—and the curtains disappear. This is the first major slippage between Horton and Pasolini. Horton’s casting of Afro-American Australian Juan Jackson dramatises the racial themes that Euro-American aesthetics plays out. The Stranger of the film was white, but race changes everything—especially where sexuality and a ‘return to the primal’ are concerned. Pasolini tended to locate the revitalising salvation of the bourgeoisie in the dark, mixed blood of the Mediterranean peasantry—but it is only a short voyage from Italy to Africa.

Peter Corrigan’s elegant use of bent wicker at the rear of the stage comes therefore to recall tepees or postmodernist ‘tribal art’. The form of the production thus echoes the content. Both show how Westerners are endlessly seduced by images they project onto Africa and the Orient. Jackson’s own musical signature is the Persian drum, reminding us that Western discourse tends to blur cultural distinctions (though a few responses suggested that this was actually reinforced for some). Jackson’s performance superbly accommodates these readings without being confined by them. The Stranger is content to offer whatever his hosts desire, to have sex with each in turn. We never know however what he himself wants, or is. He preserves his mystery because he refuses to be what the others see him as. He simply leaves.

The hysterical collapse of character, psychology and the very structure of the production that this encounter with ‘the Other’ engenders is the strongest aspect of Teorema—not least in terms of the music. The first half feels hurried, full of the angular clashes, short sections, ascensions and false-starts often described as ‘brutal’ or ‘primitive’ when musical Modernity arose. The second act however has more room to breath and pause. The inevitability and relentlessness of the first half is replaced by a more open sense of musical time in which anything could happen, as the characters tunnel in upon their own psycho-aesthetic obsessions.

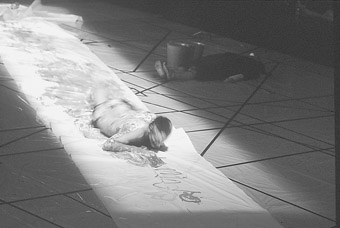

The son’s highly physical, performative drawing-style leads him to smear himself with paint and rub himself along the floor, echoing Yves Klein or Pollock. This offers no release however. The mother unrolls the Stranger’s mat, complete with his underwear. Her tormented encounters with these fetishes offer an abject “consummation”, but hardly one “devoutly to be wished.” The daughter is rendered as a pained, human camera obscura, mapping out lines between photographic subjects, including herself. Ian Scott however all but steals the show through his concentrated minimalism, replete with nameless emotion, slowly stripping as he throws off his possessions, dignity and identity, before collapsing.

Only the maid’s journey lacks this sense of self-immolation. In the film she selflessly returns to the peasantry to perform miracles. Horton’s disruption of Pasolini’s ethnological ideas however closes off this site of potential redemption. Horton’s staging does not resolve this issue, but in shattering the production’s own theatrical unity, he creates ample room for such contradictions to coexist within this richly complicated work.

Teorema, by Giorgio Battistelli, ChamberMade Opera Co., director Douglas Horton, conductor Ronald Peelman, performers Shelley Lasica, Ian Scott, Michele Heaven, Tom Wright, Barbara Sambell, Juan Jackson, CUB Malthouse, Melbourne, August 9-12

RealTime issue #45 Oct-Nov 2001 pg. 34