The Choreographic: concept or con?

Keith Gallasch: 20th Biennale of Sydney, Choreography & the Gallery

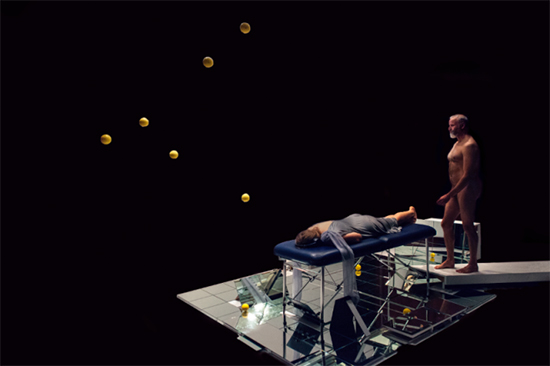

Lizzie Thomson, TACET: Rhythmic Composition (after Roy De Maistre’s Rhythmic Composition in Yellow Green Minor, 1919)

photo Document Photography

Lizzie Thomson, TACET: Rhythmic Composition (after Roy De Maistre’s Rhythmic Composition in Yellow Green Minor, 1919)

Since the 1990s conceptual choreography (and its antecedents since the 1960s) has expanded and mutated dance. At their humblest, choreographers now declare themselves directors of idea-driven works in which there will be varying degrees of dance among other things; at their most elevated, choreographers label themselves artists who make objects (dance, dance-related) for art museums. The latter works sometimes enter permanent collections and when re-exhibited display traces of the originals but will become, in turn, newly ephemeral—but objects nonetheless.

The notion of dance as object (let alone dancers as objects) can be unsettling, as has been the move away from ‘steps’ in conceptual choreography and associated Non-dance. There are fears that dance will lose its primal distinctiveness, that it is being rendered invisible—indistinguishable from the current mergings of contemporary performance, performance art and live art.

There’s been some mocking of audiences who love dance for its ‘steps,’ its anti-gravitational magic, fluidity, radical angularity and non-verbal expressiveness, for its felt pleasure and tensions. While we watch in stillness, our neural system vibrates in synch with dancers’ bodies—with any bodies, as it has from our earliest years and, indeed, in utero. For many, this is what compels us to dance and to watch dance. Other observers feel that it’s not just dance that’s disappearing in conceptual choreography, but the body.

Feelings run high over the challenge of conceptual choreography to dance. At the end of his impassioned essay “America without tears” in the current Dancehouse Diary, American cultural critic Andy Horowitz writes, “that strand of conceptualism in contemporary choreography that seeks to remove the body from the consideration of dance, when favoured by elite American arts programmers, curators and institutions, has real consequences. ‘Disembodiment is a kind of terrorism,’ and when the labouring body is erased by (white, male, of European origin) philosophical constructs, we are complicit in devaluing human lives even as we are destroying the democratic American body.”

But instead of being co-opted by galleries for “experience economy” ends, is dance simply seeking new niches in the arts ecosystem, making itself more visible and regenerating? The emergence of the term “the choreographic,” however, has further complicated a sense of dance’s place and its viability.

The Choreographic

The adjective “choreographic” has lately been definitely articled and noun-ed. Choreography, as in the making of dance, has been appropriated, metaphorised and newly theorised in order to liberate art museums and biennales from a sense of stasis, to provide expanded sensory and cerebral engagement for gallery-goers in the era of “the experience economy.” Of course there is a long 20th century history of the ‘authentic’ body from time to time intruding ‘disruptively’ into the gallery and reinvigorating our sense of art. The choreographic is the latest of these moments, enveloping and activating the bodies of those who were once viewers and, ideally, bringing into greater play a fluid relationship between artist, curator, gallery space and audience,

“The choreographic” covers dance performed in galleries (or, in biennales, on the streets and elsewhere), dance and other performances that engage with artworks, and the physical movement of gallery-goers—whether of their own volition or shaped by curators (the compelling placement of images) or by artists (choreographers or not) who create ‘walks’ or ‘journeys’ or even encourage all too willing gallery-goers to dance en masse, as was the case with Biennale of Sydney keynote speaker and conceptual choreographer Boris Charmatz’ Musée de la danse at Tate Modern and other galleries and in squares and parks.

Jenn Joy’s The Choreographic (2014) is publicised as “mov[ing] between the corporeal and cerebral to tell the stories of encounters as dance trespasses into the discourse and disciplines of visual art and philosophy through a series of stutters, steps, trembles, and spasms.” For Joy, choreography—conceptual and postmodern—becomes a role model and an infiltrating agent (it “trespasses”) for expanding notions of movement within and across disciplines and genres and is exemplified in contemporary works which in their ineffability elude categorisation.

Meryl Tankard performs Nina Beier’s The Complete Works

photo Ben Symons

Meryl Tankard performs Nina Beier’s The Complete Works

Jess Wilcox in The Brookyln Rail writes, “Joy relates this thinking to the choreographic nature of the artistic endeavor as it highlights the unfixed relationship among the maker, the image and the viewer…In this, movement, language, writing, composition and articulation emerge as tangled manifold concerns.” She adds,”…the tension of the age-old binary of mind/body dualism lies below the surface. Embodied thought seems to be what Joy is seeking.” And choreography, actual and metaphorical, offers, it seems, a way into this embodiment.

However, adds Wilcox, “Joy’s silence on performance and dance in the museum is curious considering the topic’s currency and how she emphasises visual arts in the first chapter. No doubt a great deal of recent museum performance treads the line of spectacle and is not worth spilled ink. Yet, her astute understanding of the triangular relationship between artist, performer, and audience is valuable as the prevalence of performance in the museum increases. As more museums embrace the experience economy model, they claim an authenticity for visitors.”

Choreography & the Biennale

Artistic Director Stephanie Rosenthal has placed choreography of many kinds, actual and theoretical, front and centre in her Biennale of Sydney program, yielding much discussion. In a number of forums she’s declared that she’s not attempting to institutionalise dance in galleries and is wary, for example, of the notion that dance can interpret visual artworks (“an old-fashioned art-plus-performance idea”), although performances by Chrysa Parkinson (whom I didn’t see, but who impressed watchers) and Lizzie Thomson engaged intriguingly with paintings at AGNSW. Rosenthal described bringing performance into the gallery as “interesting but painful” and “very different in theory from reality.” But she is clearly fascinated, intellectually and experientially, by possibilities for the ephemeral arts in otherwise materially oriented galleries. Her doubts aside, Rosenthal’s program and previous work represent the encroachment of “the choreographic” into the gallery if, it would seem, experimentally and with the freedom, as she mentioned, that a biennale budget and resources allow.

Where does “the choreographic” sit in the world of dance? In the form of conceptual choreography it accommodates and rationalises the radical expansion and transformation of the dance palette across recent decades—not only with dance’s increasing diversity of forms but also in its hybridising mergers with performance art, contemporary performance, live art, digital media and, emphatically, in its romance with the academy, sharing, alongside visual art, some of the most esoteric of writing and theorising. The latter was in full sway in the Biennale’s six-hour Choreography in the Gallery Salon, a mix of talk and performance at AGNSW facilitated by UNSW’s Erin Brannigan. The language of academics and curators who spoke was highly coded, sometimes obscuring insights and conjectures, while dancers spoke lyrically but also quite abstractly. Other speakers addressed the issues with a blunt pragmatism.

Xavier Le Roy, Temporary Title Open Rehearsals. Commissioned by Kaldor Public Art Projects and Carriageworks

photo Zan Wimberley

Xavier Le Roy, Temporary Title Open Rehearsals. Commissioned by Kaldor Public Art Projects and Carriageworks

Time, the gallery & the object

AGNSW curator Anneke Jaspers’ focus on time detailed museums’ “multiple templates”—their set hours, calendars, seasons, cycles, loops—and how artists working in performance are adapting to and exploiting these “temporalities.” A year at the Stedelijk: Tino Sehgal (2015), for example, comprised a 12-month cycle drawn from Sehgal’s opus with 12 live works of varying scale programmed to respond to seasonal change and varied gallery spaces. For audiences, said Jaspers, there was “no possibility of a total reading” across the year; a situation akin to showing of multiple long films and videos in exhibitions. Nonetheless, the work’s unfolding attracted a strong audience according to its curator and has been acquired for the museum’s collection, a move, says Jaspers, that is still rare. French conceptual choreographer Xavier Le Roy has also, she said, created a program of works 1994-2010 in which “a retrospective becomes a mode of production” for creating new work from old.

In these ways choreography grants itself a greater degree of materiality for dance as object with which to justify its place in the gallery—with the gallery’s archival criteria—while at the same time creating new ephemera. But it does mean that if dance steps outside of theatre time into gallery time and space, it possibly becomes something else, certainly from an audience perspective where privileged scheduling, viewing and optimal attentiveness are not guaranteed. If they are, then the evils of ‘spectacle’ are severely invoked.

Curator as dramaturg

Hannah Mathews, senior curator at Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), introduced another perspective on the choreographic in which she attempted to find equivalence for herself not between choreographer and curator but rather curator and dramaturg—a “co-imaginer” working with artists. It’s a good match and a telling one although the analogy is not a simple one: the hierarchy in performance is still largely headed by a choreographer or a director over and above a dramaturg. In a fascinating aside Mathews suggested that text (written, spoken, performed to, danced about) was more central to Biennale performance than choreography—an indicator of even higher conceptualisation or more diversification and cross-over?

Avoiding & Invading the gallery

Phillip Adams, choreographer and artistic director of the Melbourne-based BalletLab dance company described his strategies for inserting works into galleries without losing integrity and audience attentiveness and Tang Fu Kuen, a Bangkok-based, Singaporean curator and producer, sounded alarms about live performance’s potential loss of authenticity when presented in galleries.

Tang spoke of “the performance turn” in which “exhausted” museums and galleries aim “to produce subjectivity, so that individual (gallery-goers) feel spoken to.” He sees the phenomenon as a part of a Neo-liberalised culture which reduces art to well-being and lifestyle. He wonders precisely what these strategies say about art to audiences. Tang expressed concern about performance in galleries without committed audience attentiveness and in a context of competing visual artworks already rich in associations. He also highlighted a lack of care for artists performing without the usual professional safety nets and requisite budgets. Care was an issue that the Biennale curators spoke to in this forum. I witnessed the admirable Meryl Tankard performance for Nina Beier’s The Complete Works at the MCA where there was no strategy in evidence for dealing with an at times far too crowded gallery space in which staff vigorously protected the installed and hung artworks but not the dancer.

Phillip Adams, After, Proximity Festival 2015

photo Matt Sav

Phillip Adams, After, Proximity Festival 2015

Phillip Adams drolly explained how he “graduated to the gallery,” having long been averse to dancers suddenly appearing like aliens in gallery spaces in their T-shirts and whites only to be avoided by audiences. He opined that “dance in the gallery has not evolved much since the 1960s” and entails “a truckload of problems.” Adams described After (Proximity, AGWA; Sarah Scout Presents, 2015), a work he created for exhibition in which a sole visitor enters a structure and stretches out for a 15-minute encounter with Adams’ “naked mature body” (too much art has been about youth and beauty, he declared). So that the work maintains its integrity, timing is fixed and manageable, there’s a $20 ticket price, a guide and a white walkway to the installation’s black curtain. It’s better, says Adams, than offering the gallery-goer “the freedom to watch three minutes of a 30-minute video work.”

Ephemeral objects

In the first of three works presented in the AGNSW Central Court, “spatial practice” specialist Helen Grogan quietly created OBSTRUCTION DRIFT, a “performative and sculptural situation” in which gallery staff delivered stacks of chrome angle barriers used to demark function spaces. Grogan and an assistant arranged them about the court and left. Save for those in the know, viewers perhaps suspected that the activity was preparation for a work that never happened. The artist’s claim to test, in galleries, “the potentiality for obstructions, parameters and demarcations—both spatial and conceptual—to destabilise, shift, drift” was barely felt.

Melbourne choreographer-dancers Shelly Lasica, Jo Lloyd and Deanne Butterworth danced through the Wednesday night gallery crowd in their How Choreography Works, an iteration and extension of “the discussion” that comprised the 2015 original which “included original and archival performance.” With Lasica as a kind of grande dame and Lloyd and Butterworth as sometimes aberrant acolytes (displaying some exhilaratingly precise twinning of movement), the trio carved up the space and generated diverse patterns of cause-and-effect with energy, subtlety and wit, un-fazed by the casual movement of the audience. At close quarters and great distances—as Lasica opened out the length of the space—we witnessed not a totality, but fragments as we moved to gain sight or shift perspective or surrendered to the dancers’ disappearance into the crowd. Making aesthetic sense of How Choreography Works as it shape-shifted over a long duration, let alone understanding it as some kind of archive (unless perhaps we’d been committed Melbourne dance followers), proved challenging, recalling comments in the forum about the pitfalls of uncontextualised dancing in galleries.

Roy De Maistre, Rhythmic composition in yellow green minor (1919)

Sydney dancer Lizzie Thomson similarly created a space in which she danced amid the audience, engagingly, fluidly and passionately as ever. It looked like another dance in a gallery. However it was the coda to TACET that made sense of the performance for those who had not read the program notes. Catching her breath, Thomson read aloud a letter addressed to Virginia Woolf about her encounter with both the novelist’s The Waves (she’d learnt part of it to recite to single visitors to Biennale artist Mette Edvardsen’s Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine, presented at Newtown Library) and artist Roy De Maistre’s Rhythmic Composition in Yellow Green Minor, 1919, located in an adjoining gallery room.

In her letter to Woolf, Thomson recalled standing in front of the painting and finding herself “thinking about the rhythmic composition of The Waves, and how the intensity produced by reading it over and over again out loud would sometimes make me feel seasick. I had to train myself to read it without rocking backwards and forwards in time with your words. For a few years now I have been working intermittently with a score of rocking, a kind of rocking between the past and present, shifting my attention between working with embodied memories and also generating new, or renewed, movement material.” [The complete letter will be published as part of the Time has fallen asleep… project.] Thomson’s performance moved beyond apparently abstract dance into the conceptual when spoken, revealing the artist’s musing over dance, words, darkness and silence.

As Andrew Fuhrmann wrote, contestably, in RealTime about the prevalence of conceptual choreography in the Keir Choreographic Award works, “we risk falling into repetitive and needlessly divisive debates about whether this is really dance or not. Simply put: there is conceptual choreography that works, and there is conceptual choreography that doesn’t. And this is what we should be talking about.” There are many exciting, conceptually driven works, including those that with devices—and without dancers—mobilise the bodies of the public, like William Forsythe’s Nowhere and Everywhere at the Same Time, no 2, 2013, in which the audience move amid swinging pendula. It’s exhibited on Cockatoo Island as part of the Biennale of Sydney until 5 June.

Likewise, “the choreographic” might inspire a greater awareness of the creative fluidity of artist-artwork-audience relationships across and between all forms. Or it might amplify the challenges highly theorised art dance has set itself in a gallery economy hungry for commodifying audience experience, possibly at the expense of the dancing body in—as one dance loving observer put it to me—“a visual arts takeover.” At the same time, beyond the conceptual choreography prominent in the Keir Choreographic Award performance and this year’s Next Wave Festival there is a plenitude of exactingly choreographed works being created and performed across Australia without surrendering dance, let alone the body, some of it enriched by conceptualism and the far-reaching concept of “the choreographic.”

My thanks to Lizzie Thomson for permission to produce an excerpt from the text accompanying TACET: Rhythmic Composition (After Roy De Maistre’s Rhythmic Composition in Yellow Green Minor, 1919).

–

20th Sydney Biennale, Choreography and the Gallery, a one-day salon, facilitator Erin Brannigan; Centenary Auditorium and Central Court, Art Gallery of NSW, Sydney, 27 April

RealTime issue #133 June-July 2016