The art of theatrical exhumation

Jonathan Marshall

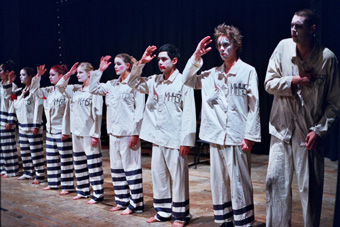

The Art ’n Death Trilogy

The Art ’n Death Trilogy consists of 3 plays from writer Adam Cass and director Bob Pavlich, each exploring the work and demise of a theatre artist: early Russian avant garde director Vsevolod Emilievich Meyerhold, fictional Australian bush poet Bill Johnson and British shock Absurdist playwrigth Sarah Kane. The staging of this ambitious project is excellent, with Pavlich’s mostly ‘Australian burlesque’ direction, John Ford’s almost neo-Constructivist lighting of strong red blocks and footlights played against a demystifying use of simple white light, and masterful scoring drawing particularly on film music. There is also an impressive, mostly young cast. Art ’n Death is a bold, superbly realised project exhibiting great sophistication in its performative dramaturgy. It is enjoyable, funny and gripping. However, it’s a flawed masterpiece, its manifold pleasures paradoxically masking the problems of the writing and manipulation of concepts.

Have Dreamed of a Time, featuring Bill Johnson, and The Anniversary of the Death of Sarah Kane are stylistically closest, sharing a rough and ready episodic, comedic structure which, especially in Have Dreamed, seems straight out of the larrikin avant gardism pioneered by John Romeril and others at the Pram Factory in the 1970s. This works well for Bill Johnson, who is an amalgam of cliches about Australian writing from Ray Lawler to Robert Johnson, early David Williamson, and Les Murray-style blokey populism. The character’s anxious turning-over of Australian national identity is particularly of this era, but there is little which signposts, let alone addresses, the dated nature of this material.

This otherwise extremely skilful exhumation and caricaturing of national writing is interwoven with a drama about the character’s inability to deal with the ridiculous deaths of his family: his baby brother backed over by the parental automobile and his young daughter loudly protesting the stupidity of her situation as she is eaten by the neighbours’ lizards. The rollicking insanity of these scenarios, including a farcical representation of the afterlife presided over by a boozy, has-been vaudevillian hostess, gives Have Dreamed a wonderful sense of corrosively acidic fun. The final revelation that Bill has retreated into imagining the scenes which the audience sees on stage so as to escape reality seems, however, to replicate the very culture of anti-intellectualism which 1970s Australian art attacked.

Kane moves only slightly forward historically, to the increasingly politicised styles of queer cabaret which married drag with performance art from the 1960s (Valerie Solanas, Divine, Andy Warhol’s Factory scene and later Britain’s Neil Jordan). The addition of a wonderfully sexy, philosophic and camp Mae West (who composed scurrilous gay and transvestite burlesques) pulls us further into the past. Former enfant terrible of British theatre, playwright Edward Bond, also appears, as a coolly charismatic analyst of social violence. This deliberately ahistorical melange recalls Jordan’s work, as well as less cohesive combinations such as Velvet Goldmine (director John Cameron Mitchell, 2001) and Hedwig and the Angry Inch (Todd Haynes, 1998).

Bond is an eminently suitable comparison for Kane, Britain’s only recently deceased angry young woman playwright, being both a theatrical avant gardist and a social realist. The addition of Mae West, though fun, is less well handled. Kane includes a fantastic scene where Bond cautions the baby Kane about social evil, before removing her from her pram and stoning it, recreating the scene from his scandalous Saved (1965). West, however, is never situated with respect to Kane, and both her inclusion, as well as the choice of Kane material featured here, emphasises her banal attempts at sexually, physically and verbally shocking theatre and dirty realism. The less derivative, neo-Beckettian language of Kane’s best piece, Crave (1998), is largely absent here, causing Kane to appear merely as the theatrical equivalent of the bad boys and grrls of contemporary British visual arts featured in the Sensations exhibition—a Tracey Emin of the stage. If this is all Kane was, then such a play about her is hardly justified.

The difficulty with the Meyerhold piece, Fainting 33 Times, goes to the heart of the trilogy’s intent. As a Communist and sometime Constructivist artist devoted to a new radical aesthetic whose very form was to dramatise the essence of the human biological machine, its social status, and the culturally-imposed impediments on the maximisation of its bio-rhythmical structures, Meyerhold makes a perverse subject for a play about the “psychological world” of the individual artist. After an initial, superb section which lovingly recreates the incomparable idiomatic physical music and intonations of Meyerhold’s theories about performance, Fainting degenerates into a Fellini-esque personal drama in which the staging’s grotesque carnivalism represents the character’s sense of guilt over failing to oppose Stalin (unfairly, given Meyerhold famously and fatally did so in a 1939 speech) and for breaking under torture. As with Having Dreamed, this replicates the venerable anti-intellectual cliche that such scenography can only represent a disordered or deluded mind. Meyerhold himself would denounce The Art ’n Death Trilogy as reactionary bourgeois art for focusing on the individual psyche. Nevertheless, in sketching the personae of 3 very different artists through a montage-like performance, Art ’n Death creates a compelling sequence of theatrical events and scenarios.

The Art ’n Death Trilogy, writer Adam Cass, director Bob Pavlich, various performers, designer Paula Lewis, lighting John Ford, sound RL Beard; Trades’ Hall, Carlton South, Melbourne, May 8-23

RealTime issue #61 June-July 2004 pg. 8