the art of going global

sophie travers on the rising tide of australian arts touring

Moira Finucane, Burlesque Macabre, The Queen of Hearts,

photo Heidrun Löhr

Moira Finucane, Burlesque Macabre, The Queen of Hearts,

2007 DRAWS TO A CLOSE ON AN EXTRAORDINARILY BUSY YEAR OF INTERNATIONAL TOURING FOR AUSTRALIAN CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE. ASIDE FROM THE MAJOR COMPANIES RESOURCED TO TRAVEL (BANGARRA DANCE THEATRE, SYDNEY DANCE COMPANY ETC) SMALLER ORGANISATIONS AND INDIVIDUALS HAVE BEEN FINDING SUCCESS OVERSEAS. BACK TO BACK THEATRE, BRANCH NEBULA, ADT, URBAN THEATRE PROJECTS, DANCE NORTH, CHUNKY MOVE, LUCY GUERIN INC, CIRCA, ACROBAT, ROSIE DENNIS, CLARE DYSON, MOIRA FINUCANE, MEOW MEOW, MEN OF STEEL, TOM TOM CLUB…THE LIST GOES ON. WHAT IS BEHIND THIS UPSWING IN ACTIVITY? IS IT FASHION, CHANCE OR THE RESULT OF A SLOW ACCUMULATION OF SHEER HARD WORK? WHAT ARE THE MOTIVATIONS AND MACHINATIONS OF AUSTRALIAN ARTISTS ON THE INTERNATIONAL SCENE AND THOSE WHO SUPPORT THEM?

I talked to the few producers promoting Australian performing artists internationally and, as you’ll read in the next edition of RealTime, to the companies themselves. Wendy Blacklock at Performing Lines has been in the business for over 25 years, first taking an Australian Indigenous theatre company overseas in 1982. Marguerite Pepper has a similar history and both refer to Justin McDonnell, now in the US, as another pioneer of their generation. Certain funders have been around long enough to follow the work of these producers and their artists, including Amanda Browne, who has over a decade of experience as manager of the International program of Arts Victoria.

motivation

All these individuals agree on why artists choose to tour. There is the fundamental drive to keep working, to fill the calendar and preserve livelihoods. There is the sense of relevance and connection to a world of diverse cultural contexts. There is the chance to meet other artists and absorb new ideas. There is, sometimes, a financial benefit to be gained. With luck, new presenters with touring connections see your work. Occasionally there are even commissions and collaborations. Always there is the increased cachet and resultant opportunities at home that follow success overseas.

Nobody can be sure whether the increase in touring of 2007 is an all-time high. There is no consolidated data, yet producers and funding bodies confirm that activity has been building over the last decade and looks set to continue. All recognise that success breeds success. A large part of international touring is confidence. Any sense of disenfranchisement, because of Australia’s great distance from other markets, is quickly dispelled by a sell-out season at a major arts festival. The producers elaborated how much of their role is about coaching and encouraging artists, as much as it is about tour booking and negotiations.

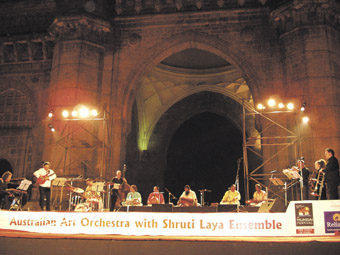

Australian Art Orchestra Sruthi Laya Ensemble, Into the Fire, Gateway of India Mumbai

global engagement, global issues

All agreed that Australian contemporary performance is currently expressing an unprecedented self-confidence, particularly in Indigenous and cross-cultural idioms. Mature performers such as didjeridu player Mark Atkins are leading new generations of artists into rich cultural dialogue. Amongst cross-cultural productions touring in 2007, Marrugeku’s Burning Daylight featured in Zurich’s Theaterspektakel festival and Urban Theatre Project’s Back Home travelled to Toronto’s Harbourfront Centre. And the rest of the world is particularly interested in this distinctive Australian discourse. Marguerite Pepper noted that the Pacific Rim focus of the 2007 Australian International Music Market in Brisbane was extraordinarly well received, by Europeans in particular. She cites the young Brisbane-based didjeridu player, Tjupurru, as a runaway success. Pepper talks of a coming of age of the sector but also of a more enlightened support structure which allows for risks to be taken with less proven artists or projects of scale, unconventional settings and more complex contexts.

Contributing to a global discourse is a sign of Australia’s cultural maturity. Benefiting from a cyclical change of taste and fashion is a less predictable but equally energetic connection. Australian dance, physical theatre and circus is the choice of European presenters jaded by their own artists’ current predilection for conceptual anti-theatre. Just as Meryl Tankard’s ADT, Legs on the Wall, Stalker and Circus Oz were feted in the early 90s, Splinter Group, Circa and Garry Stewart’s ADT now break into markets where virtuosity is thin on the ground. The hybridity of Australian work and its ease in cutting across forms, media and ethnicity has been praised by presenters such as Maria Magdalena Schwaegermann who favoured Australian work in her Theaterspektakel festivals in Zurich.

support mechanisms

While fashions have always come and gone, the difference now is that Australian artists are resourced to take advantage of them and are aware of and involved in the international arts market in ways impossible to imagine a mere decade ago. Web-based communication is making promotion easier as are cheaper travel costs. Blacklock spoke vividly about her trials raising a seemingly impossibly $100K to tour to Expo86 in Vancouver. In those days there were no specific programs to which companies could apply for travel support and this alone created an enormous hurdle. Now, as all agree, the range of sources of support encourages companies to invest in international presentation as a viable aspect of their business.

Producers and funders alike found it difficult to say if funding programs drive activity or vice versa. There was unanimity that Australian artists are professionalising apace and that many have formed coherent strategies for international activities. While some have done this in response to specific new funds designated for business development, such as Victoria’s SCOOP program, or the Australia Council Theatre Board’s International Market Development Strategy for Theatre for Young People, others have siphoned core funding into international activity as the most sustainable aspect of their business. Circa and Strut & Fret Production House (both companies are Brisbane-based) are examples of this entrepreneurial approach. Acrobat, who invested heavily in their career ever since their early borrowed bus and starvation tours, did it the hard way but are finally making a reasonable living not least in the UK and Europe where they are enormously popular.

the big picture

Sandra Bender, the new Director of Market Development at The Australia Council, is a Canadian who comes to the current situation with a perceptive take upon the successes and limitations of previous programs designed to promote Australian contemporary culture internationally. She recognises the intention of programs such as Undergrowth in the UK and the multi-year investment in Berlin as serious attempts by the Council to engage in reciprocity and exchange. She also realises however that such high profile, focused activity can be supplemented by subtler, smaller projects with longer lifespans. The Australia Council’s investment in arts markets is likely to diminish, and whilst the producers cited APAM, CINARS and APAP as the source of many of their most productive international relationships, they all agreed that nothing much materialised from the conversations engaged in there for years, and sometimes not at all. Bender plans to resource companies to tailor-make their international networking and relationships more strategic, aiming for future collaborations, co-productions and commissions. This approach has borne fruit for Arts Victoria, which has offered specific programs for international activity since 1995. Encouraging Victorian companies to make their own explorations, while still taking advantage of national initiatives such as The Barbican’s Ozmosis project or the Pittsburg Cultural Trust’s Australia Festival in 2007 makes the best of both worlds.

As the sources of support for touring proliferate the volume of activity naturally increases. The federal government’s recent announcement of the Australia on the World Stage program, to be implemented by AICC (the Australia International Cultural Council, a consultative group chaired by the Minister for Foreign Affairs and composed of leaders from government, the arts and business) is a promising new source of support, the details of which are not yet available. While this program will continue the focus upon key markets shared by the Department of Foreign Affiars and Trade (DFAT) and the Australia Council, the producers all noted that new markets are opening up to Australian artists. As the populations of Asian countries such as South Korea and China become more prosperous and more attuned to their role as global citizens, the doors to their cultural institutions are opening. Through proximity, something of a track record (at least compared with European artists) and the out-and-out encouragement by funders, Australian artists are making headway in Japan, Korea, Singapore and China. Artists in Western Australia recognise that performances in Asia are often less expensive to organise than a national tour.

pleasures & pitfalls

While there is a unanimous and hearty engagement with international touring among artists, producers and funders, it’s clear that there is an equal distribution of pleasures and pitfalls along the path to international success. Tales of lost freight, visa shenanigans, critics without context and language issues are balanced with accounts of budgets surpassed, standing ovations, return invitations and five star reviews. Most companies and artists report a fine balance between the cost and gain of their international activity and iterate the comments of funders and producers, confirming a lively interest and investment in this area and optimistic, if cautious views of the international future for Australian contemporary performing arts. In RealTime 83 I’ll report on how individual artists and companies view the value of their international touring.

RealTime issue #82 Dec-Jan 2007 pg. 32