Teaching new media: aiming at a moving target

Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski

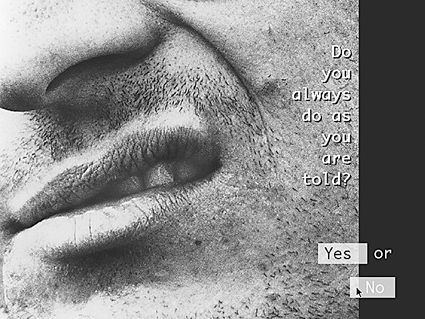

Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski, User Unfriendly Interface

Tertiary institutions everywhere are setting up new media departments, their computer labs bulging with students eager to skill up for the 21st century in which it seems everyone wants to be a web designer.

Courtney Love, recently writing about music pirating, posted to a list serv:

I have a 14-year-old niece. She used to want to be a rock star. Before that she wanted to be an actress. As of 6 months ago, what do you think she wants to be when she grows up? What’s the glamorous, emancipating career of choice? Of course, she wants to be a web designer. It’s such a glamorous business!

Glamorous? Well certainly ubiquitous, the landscape is littered with URLs. Bus and taxi backs point to insurance websites, graffiti points to net.art sites, Telstra has back buttons on their billboards, the accepted interface norm dumbs down another notch. The web is the area where students know they can get work right now, in spite of some employers’ proud boasts of huge burn-out rates; if you look remotely like a plug’n’play pixel monkey, you’re in (for the moment anyway). We wonder about a time when every business has a website, there’s a glut of people out there with web skills who can’t get work and nobody knows how to bang a nail into a piece of wood, or use a welder.

According to Kathy Cleland, new media curator and lecturer:

There is a huge student demand for courses at tertiary institutions which have anything to do with multimedia and this is increasing exponentially. An introductory multimedia course I taught at the beginning of 1999 had 30 students; the same course this year had 95 students. There is also a tendency in full fee paying institutions to over-enrol students to maximise profits which leads to very large tutorial sizes and consequently to staff burnout with huge marking loads. I have been teaching at an institution (half university owned and half corporate) that has 4 semesters per year so there is also very little time for research and skills upgrading.

The difficulties in teaching digital media arise from the breadth and scope of the area. Due to its hybrid nature and links with cultural studies, communication theory, visual design, visual arts, computer science, film studies etc, new media projects typically require a vast skillset and cover a range of considerations which are not necessarily able to be delivered within the one faculty (as lines are currently drawn) or indeed by the one student. This is why it is particularly exciting for us that the School of Design, University of Western Sydney, Nepean is potentially merging with the Communications and Media School. Students currently can choose to undertake subjects across school lines, but it is difficult to “synthesise” school approaches. As new media becomes less new and more consolidated in its own right, we will see some of the moving targets come into focus enough to better track them.

The pedagogical dilemma is the fact that the ‘mission statement’ doesn’t yet exist. There is no agreed canon. It’s too early to be able to draw on a history of interactive media, as we have for film and TV. But then again, that’s often the attraction. It’s new and uncharted, with a plethora of opportunities for innovation.

There is a strong trend towards online education, which makes life easier, or at least more efficient for both students and teachers. List servs can be an extremely useful teaching apparatus, enabling the whole group to communicate their ideas to each other, and also for lecturers to give feedback easily. Online education is going to be a huge growth area and will ultimately challenge the traditional university structure. The fees charged for these courses are much lower than current student fees and you can do a course with the university of your choice anywhere in the world. There are also a lot of corporations looking at education as a vast, extremely lucrative untapped market—so education is not going to remain the exclusive property of universities for much longer. A friend who recently moved to Canada to take up a university teaching position wrote describing a rather dystopian vision of future online education:

Moving to Canada was a mistake because the university I came to is trying really hard to be like a corporate online course farm…I have to be managed and work in a cubicle.

Here it is often visual artists who are teaching digital media in design schools. Practitioners have a wide practical skillset acquired through an exploratory approach to self learning as well as from working in different roles on varied projects, and are experienced in collaborative working models. In our own practice, the aim is to teach people to integrate their creativity more deeply into the computer environment as well as to teach within a cultural context. We encourage practical teamwork as well as learning the toolset, which is an easier task in design than fine art. The fine art world, for all its postmodern rhetoric, is generally trapped in the modernist paradigm of artist as lone lone hero. Consider the promotion of young British artists (or YBAs as they are known) by the advertising firm/art collectors/government consultants, Saatchi and Saatchi, in London. These artists are like popstars, the more famous and controversial the more likely they are to sell their work. And now there are billboards at Heathrow airport of Tracey Emin selling Bombay Sapphire Gin. First artists become products to be promoted and, when famous enough, they can be used to sell other products.

New media artists tend to be critical of the current fine art institutions. We like to employ a hacker mentality in our approach not only to technology but systems in general, whether they be social systems or ‘the media’ themselves. Our interest in the area of new technologies is fuelled by a mixture of scepticism (who is excluded from technotopia and why would anyone want to live there anyway?) as well as enthusiasm for the playful possibilities of digital media. Our own work which includes the User Unfriendly Interface, Paranoid Interface and the Bio-Tek Kitchen game patch deconstructs current interface and game paradigms, subverting them to reveal that our experiences are being increasingly mediated by new technologies and that there are dangers hardwired into this trend.

At UWS we introduce students to different online and gaming cultures, cyberfeminism, hacktivism, and ‘Tactical Media’, which is the rather slippery term used to describe the practices of a loose alliance of international media theorists, artists, designers and activists. We also expose people to the enormous amount of interesting and playful work which is being made around the globe. Often what excites the students excites us and, as play and pleasure have always been an integral part of our work, we encourage people to do the same and sometimes get great results—work which can inspire and entertain us all.

Josephine Starrs and Leon Cmielewski are artists and lecturers in new media at the School of Design, University of Western Sydney, Nepean. Their latest work Dream Kitchen is an interactive stop motion animation CD-ROM. See Working the Screen

Thanks to Robyn Stacey and Sarah Waterson (School of Design, UWS Nepean) and Brad Miller (College of Fine Arts, UNSW), for their valuable input into this article.

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 8