Talking it over

A selection of responses to the 1997 Sydney Festival

Royal de Luxe Le Peplum

The focussing of the festival around Circular Quay, shows on and in the water, and the concentration of the timetable into two weeks, plus some innovative and thematic programming with an intelligent populist edge (some of it free), is Anthony Steel’s legacy to the Sydney Festival. As several writers in the press have advised, Leo Schofield would be wise to build on Steel’s successful strategies. At a stiff farewell for Steel at the Town Hall, one rude wit observed, “If they’re so bloody grateful to him, why don’t they give him an extra $2 million and invite him to stay instead of getting old ‘two lunches’ in”. The common assumption is that Leo is going to offer us a middlebrow menu, high on stodge, low on stimulating new Australian tucker. The other assumption is that he’s going to get a lot more money to do it, and otherwise presumably wouldn’t have taken the job on. But will Leo in Sydney be the same as Leo in Melbourne? Well, Bob Carr certainly wishes it (“a truly international festival”) devoutly, and tactfully said as much publicly the day before he farewelled Steel. Steel was gracious to a fault in his farewell speech and clearly had the crowd on his side.

When you stop to think, after two weeks of non-stop festival and fringe intensity, the festival was framed for the first time, as a dinkum festival should be, by what was said about it. Steel got thrown off 2GB by a righteous Mike Gibson (a real opportunity to unleash a dislike of arts ponces?) for using the word “bullshit” in response to Jim Waites’ Sydney Morning Herald review of Wole Soyinka’s The Beatification of Area Boy. Nigel Kellaway got to air his anger over the reviews of the Colin Bright-Amanda Stewart opera The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior when interviewed by Jim Schembri in The Age and composer Colin Bright got a letter in the SMH.

Nigel Jamieson’s Kelly’s Republic also unleashed the odd letter to the editor and a lot of talk amongst artists about why it didn’t work, why Jamieson hadn’t got a writer in to shape (and edit) the work, why he bothered to appropriate the bobcat ballet from Red Square, why he didn’t exploit the Opera House forecourt site instead of going for yet-another-rock-opera-scaffolding-look, why he and the festival would even bother with the Kelly story. Healthy questions, but lots liked designer Edie Kurzer’s big ‘Nolan’ Neds.

Post-show Laurie Anderson crowds burbled about whether Laurie had gone reactionary, turned hypocrite, misread the technological moment; and why she was reading aloud, talking so much and not singing their favourite toons? It was a good debate and still a very good show. Would they have tolerated last year’s unplugged reading gig? Molissa Fenley also generated a lot of heat. Despite several visits to Australia she’s never hit it off with the dance community. They turn out for the shows and leave scowling and muttering. I couldn’t catch the words.

Neil Gladwin’s Lulu for Belvoir Street generated only nostalgia for the Jim Sharman-Louis Nowra version for Lighthouse (Adelaide, 1982) which was more than half good, especially in Judy Davis’ Lulu—wisely light years away from the Louise Brooks’ interpretation. Davis’ Lulu was all the more dangerous because the men and women attracted to her failed to see the manic energy that drove her and would destroy them…and her. Gladwin’s Lulu is a pouting teenager who’s into jazz ballet (as a sex substitute?), and the lesbian scenes are as about as coy as you could get.

The Beatification of Area Boy suffered a slow opening night in a difficult theatre, consequently most of the talk was about whether or not it was a good play badly done, or a middling play quite well done. The issues were left aside. Soyinka’s account of corruption in modern Nigeria is frightening: the casual mix of superstition and economic opportunism is as scary in its own way as the everyday of fascism. Good humour and communal music don’t alleviate the fatalism that increasingly pervades the play. There’s little humanist goodwill at the end of Area Boy. Despite, or even because of, act two plot machinations, this is a vision close to despair. Lucky Perth to have Soyinka on the spot to talk to, to exchange the words about the play that weren’t spoken here (save a few in an interview on Arts Today).

The rest was talk about what you didn’t get to see, and why you should have made the effort: for example, how good Royal De Luxe’s open air spectacle parody of epic movies, Le Peplum, was, even though it was about nothing more than sheer production cunning and theatrical silliness—a (miniature) city crushed by the feet of a giant pedal-operated Colossus, the ritual opening of hundreds of litres of low fat milk for the obligatory naked bathing scene, a stunning naval battle, a wretched Odorama machine. See Le Peplum, Perth, and believe it.

Some of the talk was about why the best two shows in the festival, Denise Stoklos’ darkly hilarious and virtuosic Mary Stuart and Casa were, for the most part, poorly attended? Too many words? Too manic? The wrong word of mouth?

Yo, Leo, at a time of minimal arts coverage on the media, surely it’s time for the Sydney Festival to get into a bit of serious talk. Why leave it all to Writers’ Week? Other festivals field daily talks and panels, not always well done but with the potential for deepening an audience’s commitment to a festival and to caring about the issues that artists engender. Here’s some of the buzz on the 1997 Sydney Festival. Keith Gallasch

Molissa Fenley, MCA; Rishile Gumboot Dancers, Playhouse, Sydney Opera House; Chunky Move, Bonehead, Seymour Centre

Watching her performance at the MCA, I began to think about Molissa Fenley’s face. These days her body doesn’t move so frenetically as in the days of Hemispheres or the solo Rite of Spring I saw her perform in 1984 and 1990 respectively. In these three short works she is more minimal, essential, ethereal, modernist maybe. These are the words we toss around as we stand outside the MCA afterwards watching Xavier Juillot’s tiger tail sculpture dancing in air outside the Opera House. It’s not Molissa Fenley’s sculptural movement that engages me—except for those moments when she lets herself fall from grace, shifting her centre of gravity sideways or slipping at the knee. They move me forward on my chair, but it’s her face that takes me in. In Savanna, I try to concentrate on her elegant arms, adjusting my own body to yet another uncomfortable audience vantage point in this most unsatisfactory of performance venues (creaky stage, bagpipe music filtering through the windows). Molissa Fenley is a dancer much admired by composers because of the serious attention she pays to music. As she dances with Peter Garland’s piano composition, Walk in Beauty, you sense two works in dialogue. But it’s in the second piece, Trace, that I fix on her face. Here she dances first in silence and then to the human voice—on this night Anthony Steel reading appropriately fast and deadpan a vertiginous text by John Jesurun about a man who has lost his memory and finds himself caught between the warp and the weft of a woven carpet.

Why her face? Maybe I’m wary of the idea of bodies as universally legible. Two nights ago watching the Rishile Gumboot Dancers I cursed the festival for not translating in the program the songs the dancers were singing. Without words, what was I to read from these thin, muscled bodies from Soweto dancing this unlikely music in big boots? With no knowledge of the traditions of these movements I rely on the shape of the performance to connect me—the rapport between the dancers and with the audience, their casual animation and sophisticated sense of play, the way they move from everyday talk to complex musical rhythms slapped on boots and bodies; the way this becomes heightened performance and then falls so easily back into the rhythms of daily life from which it has sprung.

Faces are generally easier to read than bodies—except dancers’ faces. Eleanor Brickhill says that dancers sometimes look like they’ve been called to the door at midnight. Drawn in by Molissa Fenley’s face I watch her move through this dance. It’s as if she’s trying to say something on the tip of her toe. At one moment she looks inward, as if she is being moved by the music, or her own body, or possessed, infected by some energy. At other times she is blankfaced, unmoved, going through the motions. Then she’s alert, watching herself move. Through the subtle changes in her face I read a body in dialogue with itself and with the music or text, trying to articulate for an audience something that in the end can’t be said. In the last piece, Bardo, her tribute to Keith Haring, this feeling is most literally manifest. Here her face is serene as she enters the underworld, the place between death and reincarnation in Buddhist belief. With Somei Satoh’s enveloping Mantra she moves in swoops and glides, scuffs and reaches, nodding occasionally in the direction of Keith Haring’ s gestures in angles and turned toes. Here she moves through a place where words are dissolved, space reconfigured. Here all that remains is the will to move from left to right, over, up and through. The light fades on her mid-movement.

Molissa Fenley only did two shows for the festival and a talk with video about her early collaboration with Keith Haring. This was her first ever performance in Sydney but clearly not meant as a major event. She received a somewhat ho-hum response and copped one of the most vitriolic reviews I’ve read, from former ballerina and foot-in-the-door TV journalist Sonia Humphrey in The Australian, who found the dancer disappointing in every way. “She doesn’t do floorwork…nor does she jump… she doesn’t spin either. Most disturbingly, she does not emote.”

While the dance community might have been just as ambivalent about Chunky Move’s Bonehead, they were quiet about it. This one was a hit with audiences and it certainly scooped the critical accolades. “A bold achievement. …Disturbing undercurrents beg more thoughtful examination” (Jill Sykes SMH). Makes you think—though nobody seemed keen to elaborate on what it makes you think. All it made me think was about all the other moralistic dance narratives I’ve seen about big bad cities full of alienated humanity. It seems Gideon Orbazanek said something off the top of his head like, “David Lynch goes to the ballet” and Bonehead was suddenly attributed with surreal vision. Weak jokes passed for “savage satire”. A flip reference to David Cronenberg’s Crash in the work suddenly claimed for it equal intelligence—“something of Cronenberg’s dark grotesquerie although fortunately with infinitely more intriguing results”, said Deborah Jones in The Australian.

Gideon Obarzanek’s comic strip choreography in Fast Idol at The Performance Space two years ago was inventive and hinted at something more substantial to come. Since then he’s created part two in Lurch (performed by Nederlands Dans Theatre in September) and part 3 in Bonehead, and according to the press is turning out “one gobsmacking dance work after another” (Sun Herald). What was missing from Bonehead was any sign of thoughtful examination. Maybe in the end there’s not much more you can do with that Wham! Bham! Kerplunk! stuff. I found it empty headed. For all its jumping, spinning, emoting stabs at meaningfulness, it had nothing to say about sexuality or violence or, importantly, dancing. Dead-eyed dancers paraded costumes, mouthed banalities and moved from headlock to simulated sex, musical collage nodding in agreement. Makes you think. Virginia Baxter

Virtual Lagoon, Michel Redolfi

photo Christoph Gerigk

Virtual Lagoon, Michel Redolfi

Virtual Lagoon, North Sydney Olympic Swimming Pool

Virtual Lagoon, the underwater sound installation courtesy of French composer Michel Redolfi and team, was a great idea for a nation that has great sporting and athletic activities written in its stars. The decision to put a symphony under water, or more to the point, on the bottom of the local Olympic swimming pool, was a stroke of genius.

Virtual Lagoon was not billed as an art event as such by Michel Redolfi in his introductory remarks but as an experience to be had, that needed no understanding, decoding or analysis. All you had to know was that the underwater harmonic environment was created by the interaction of moving bodies with submerged optical sensors; that we the participants were the orchestrators of the event, and so get to it! One hundred people charged for the pool, brimming with excitement and near hysteria, to dive, swim, float and snorkel their way up, down and under the water, to hear and feel ‘real coral life’ courtesy of our very own Barrier Reef. The score consisted of the ‘noise’ of mammal fish and mollusc marine life with a bass track overlaid with a glorious soprano interspersed with text (most notably some expletives in a male voice that punctuated the otherwise ambient soundscape).

It was claimed that one could create a relationship with the gigantic pebble sculptures by Lyonel Kouro that inhabited the bottom of the pool, offering, said the program, “a vast Zen Garden to explore”. Well try as I might, the Zen pebble remained true to its name and spoke not to me at all.

From inside this spacious underworld, looking up through the watery ceiling, the image of the outside world looked soft and unreal. On this particular evening it was chilly and whilst the light rain contributed to the experience, we really needed oxygen tanks because the best place to be was under so that this symphony could be appreciated in full. Fighting for breath from under or floating on the surface with snorkels was ultimately frustrating. Having to constantly navigate kicking feet, flailing arms and potential head-on collisions, in the end the event became a pool party, and whilst the technology was obviously sophisticated, the event was simplicity itself. Victoria Spence

Sonic Waters, Neilsen Park

This was a free Sydney Festival event and as such had drawn a blend of suntan-clad inner city sophisticates, North Shore matriarchs and their attendant broods, a few arts junkies like myself and working class families from the West. Some, armed with masks, snorkels, goggles were obviously here for the submarine sound experience. Others just out for a Saturday picnic and swim were wondering what the hell that thing was floating out near the shark net. The program said it was meant to be a giant inflatable jellyfish inspired by Matisse’s “Le Bêtes de la Mer”, but it looked like a huge buoyant Chupachup wrapper. The nine wooden poles that held up the netting were decorated with blue and white ripple strips meant to invoke another Matisse painting, “La Vague”, and to appear like vertical waves or ripples emerging from the real surf. Algae-patterned weather vanes sat atop each pole, spinning and buzzing in the breeze. Apparently, the only way to hear the music was to immerse oneself, so I stripped down to my gaudy Speedos, donned goggles, waded through the mild shore break and made the transition to underwater space/time.

Sound coming from everywhere and nowhere. I’d been told sound in water travels four times faster than in air and only ten per cent of it is picked up by the eardrum. Ninety percent is heard by bone conduction, mainly through skull, jaw and neck but with very limited dynamic range as only certain frequencies register. New agey keyboard music washes over, under, around and through me, but this is deeply layered and thoughtfully constructed. Mutator software (developed by computer artist William Latham and mathematician Stephen Todd) “grows” music organically in controlled fractal expansion through genetic algorithms that progress in cycles of birth, growth and decay. Chaos theory techno-aesthetically tamed. Waves of pre-recorded, pre-equalized natural marine sounds, whale and dolphin songs, tinkly synthesiser motifs, cascades of ethereal flutes and woodwinds are introduced into the stew by the composer, Michel Redolfi, doing a live mix from the balcony of a hut adjoining the beach, assisted by his two sound designers Luc Martinez, also from Nice in France, and Daniel Harris from New York, both composers themselves.

I’m getting drunk on sound in these heady sonic waters. You can actually feel the music vibrating through your body. I need some air. I float on my back, hanging off the jellyfish, my head and ears still below the water, still absorbing the sound field, looking up into blue sky heaven, although the coldish salt water and rolling surf intermittently break my reverie. This could be bigger than float tanks and much more interactive and user-friendly. With a mild shock the hushed and accented tones of the composer’s voice break in, informing us the concert, which has now been going for seven hours, is drawing to an end. He lets us down gently by slowly fading the music and letting the natural submarine sound environment of far away jetcats, ferries and breaking surf, re-establish itself and us in real time.

Drying myself off on the beach I wondered how I was going to effectively convey the gist of this transforming experience to someone who wasn’t there. In the end it was best summed up by the sight and sound of a young girl running from the water, long hair flying, throwing herself down beside her mother who was absorbing radiated waves of a more visible kind and blurting out, “Mummy! Mummy! The water’s full of music!”. George Papanicolaou

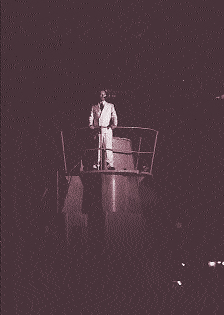

Clive Burch as the Narrator in The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior

photo Karen Somma

Clive Burch as the Narrator in The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior

The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior,

The Song Company, austraLYSIS

The Eighth Wonder and The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll are entirely predictable recent operas, their dramatic shapes inherited from the 19th century, their music closer to the musical than to the significant operas of the 20th century. The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior, on the other hand, constantly and engagingly surprises. Although musically it inclines to an accessible modernism—save where it trips into rap and rock or achieves a sustained open-ended lyricism—this opera is theatrically (in the interplay of composition and libretto) a potent contemporary work. Some of its power was unleashed in its premiere production on and in the water, a barge, a yacht and HMAS Vampire on Darling Harbour. Its Australian antecedents and companions are the music theatre works documented in John Jenkins and Rainer Linz’s timely Arias (Red House Editions, Footscray 1997). Many of the most interesting of the cited works parallel contemporary performance in their play with meaning, states of being, narrative and site. You cannot bring 19th century expectations to these works. Those who have seen Einstein on the Beach—or, more pertinently, Robert Ashley’s Improvement (Don Leaves Linda)—will know the pleasure born of patience when confronted with new opera. Even so, any opera, even the most conventional, renders words and narrative unintelligible from time to time as music drowns words, as the demands of the notes distort words into sound, or, as is most often the case, it is sung in another language.

I invoke ‘intelligibility’ because it was the issue with which the production of The Sinking… and the librettist in particular were punished in reviews—despite aspects of the work being praised. And while I would be party to some of the criticism (there were many distances involved which made the audience work too hard, lose their attention, stare into the dark for action that was elsewhere or underlit) I had no more or less a struggle with the work than I’ve had with many an opera or music theatre work. Unlike plays and musicals, operas do not often make for a complete experience the first time around. The movement from impressions to understanding is gradual. There was however, much in The Sinking… that was lucid, much of the libretto that was amplified, even made quite literal at times, by designer Pierre Thibaudeau and director Nigel Kellaway’s exploitation of the site, use of projections, of spy thriller imagery, and of sound—exquisitely designed by Kevin Davidson. The clarity of the scoring and fine ensemble playing of Bright’s music by austraLYSIS, conducted by Roland Peelman, invariably created space for the singers’ voices. The physical and theatrical confidence of the Song Company was amazing given that acting is not their business—aided by Kellaway’s understanding of the non-psychological portraits in Stewart’s libretto. Even so, the desire as an audience member to understand was strong, even when absorbed by the production’s dramatic images and sounds. Those of us who purchased a program—synopses should have been distributed free—and got time to read it in the fading light were no doubt advantaged.

The particular challenge of Amanda Stewart’s libretto is that it operates both from narrative episodes (not always causally linked) and, especially, from a rich variety of voices (created, documentary, fluid, fragmented), and while individual moments and shapes are easy to grasp—a love duet, an interrogation, a monologue of loss—assembling the whole is more a reflective than a logical act. Even so, the overall progression of the work is chronological, once initiated by the ghost of Fernando Pereria (the photographer killed in the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior) emerging vocally from an eerie rumbling bass underworld. (There are too many like pleasures in the work to mention here.)

I hope that The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior gets a second production, so often the vital opportunity for any opera’s future. While its creators are enamoured of the work as site-specific, a theatre (or other interior space) version with the same creative team could give the libretto its real chance, and a clearer indication how expertly Bright has responded to Stewart’s idiosyncratic use of language and made it his own. This first production warrants praise in every department. It was true to the ambitions of the work in scale and detail as it ranged across a battleship, through water and light, in the sustained and chilling wind of an atomic blast, and the greater betrayals and acts of complicity that constellated around the sinking of a protest vessel. Along with Denise Stoklos’ Mary Stuart and, on the Fringe, The Geography of Haunted Places, this was one of the most significant events of the 1997 Sydney Festival, whatever its shortcomings at this stage of its development. Its meanings, its engagement with the politics of the Pacific of which we are a part, and the language in which we are thus embroiled, give it relevance and urgency. Keith Gallasch

The Gypsies, Gregorian Chant Choir, Narasirato Are’Are Pan Pipers

Up to a year ago I imagined that gypsy music was the kind of thing I used to hear in Balkan restaurants in Hindley Street, Adelaide. I’ve never been that keen on virtuosic violin playing. But the film Latcho Drom changed all that, portraying a culture starting out in Rajasthan and spreading west to Spain and the UK. The live concert was analogous to the film in its presentation of the range of gypsy music and culture. A guy on a microphone gave you the story, rather like “gypsies for the masses” or “ethnic night at the opera house”. The tone was patronising and the narration unnecessary.

But the musicians created a sense of cohesion, despite cultural differences, bound by soulfulness, passion, grief, pain dealt with through music. As you move west in the film, more grief is felt in the music especially songs about Auschwitz.

For me the concert opened up the terrain of gypsy culture and music as opposed to the loose label of ‘world music’. It was interesting in terms of influences. I could hear in the Rumanians (trumpet, clarinet, alto sax, piano accordion and double bass) an influence on Michael Nyman, who uses the same instrumentation and has the same drive. A friend said it sounded like Charlie Parker had influenced the Rumanians! But it was more likely a historical connection with the gypsy music of the Nile (three oboe-like instruments with double reeds not unlike the Indian shehnai). Being a percussionist, I was inspired by the Rhajastanis beautiful, melody-driven drumming. (Ravi Shankar has drawn on this tradition and has performed a work with their dancer.) You can hear the folk origins of Indian music.

It was a night of connections, of musical anthropology. The attempt to do one piece together at the end wasn’t so successful, some participating more than others. But it did give time for the Egyptians to set up in the foyer where they sold instruments, CDs and tapes much to the astonishment of the Opera House staff.

Out in the open, I really enjoyed the free Quayworks performances by the 12 Narasirato Are’Are Pan Pipers from the Solomon Islands who played to big crowds. What was striking was the percussive drive and power of the music with the bamboo poles on the ground creating a bass line. Although they’re pipes, they reminded me rhythmically and tonally of my own boobams (octaban drums). Robert Lloyd

Concert of Glass, Government House, from della Laguna, presented by Contemporary Music Events

The Concert of Glass, held at Government House on January 17 as part of the della Laguna series, was a mixed success. A solo work for guitar, Gabriele Manca’s In flagranti, expertly played by Geoffrey Morris, was both the most glass-like and most interesting piece of the night. Brittle, complex and delicate, it had all the absorbing qualities of fine glass. Morris later combined with Carolyn Connors, playing glasses filled to varying levels, to perform bittersuss by Gerhard Stabler. This demanding work, built on silences and low dynamic range, should have been scheduled earlier in the concert, rather than at the end. Other works on the night were either too slight or too unformed to contribute much to the theme. The venue, however, was a plus, providing a sense of Sydney’s colonial history—although sightlines at the back were virtually non-existent. John Potts

Composing Venice, Government House

There are moments when you know there is an audience for contemporary music in Sydney, and this was one of them (the other was 10 new music works at Toast II Gallery, November 1996). Overall, della Laguna (“of the lagoon”) drew sizeable audiences with its program of rarely heard works ranging from Byzantine times to recent Venetian and Australian works. A curated program (Jennifer Phipps, Ross Hazeldine) as the musical centre of a festival makes a lot of sense, especially when it’s tied into the wider water imagery of the Sydney Festival and the use of intimate venues, Farm Cove and Goat Island (and a web-site with views of Sydney and Venice). Composing Venice was an ambitious concert. Save the brief opener by Claudio Ambrosini (Laura Chislett Jones on flute), the other three works were substantial. Gerard Brophy’s SENSO…dopo skin d’amourdo was given a warm, sensual, almost lush reading by the Seymour Group. Raffaele Marcellino’s Fish Tale was dark and witty by turns, even the sung bouillabaise recipe resisted cuteness, and the fourth movement, “Death”, was theatrically potent, the singers’ mouths locked open before lurching into a song of caught breaths and “unvoiced utterances with a single verse from one of the pentitenial psalms”. The Song Company, conducted by Roland Peelman, acquitted the whole work, “an allegory based on the narrative of Schubert’s The Trout” with conviction and verve. Let’s hope they keep it in their repertoire, it’s much more than a crowd pleaser. The second half of the concert was devoted to Luigi Nono’s Das atmende Klarsein in which the Song Company, on stage and miked, delivered long, gently shifting chordal shapes, alternating with Laura Chislett Jones playing bass flute with a shakuhachi breathiness from the balcony above. The third component was sound designer Kevin Davidson shifting Jone’s flute sound round the audience. Despite the dynamism of the flute writing and the displacement of the sound, the overall effect of the work was sublimely meditative. Keith Gallasch

Water Stories, Canberra Youth Theatre and the Song Ngoc Vietnamese Water Puppetry Troupe

Here was a mixed bag and in the oddest of environs, the IMAX cinema looming over us promising the “World’s biggest Movie Screen”, a tatty fun fair behind us beefing out offers of stomach churning pleasures, and several peak hour freeways growling across Darling Harbour. And what were we watching and just managing to hear? Subtle, sophisticated and witty Vietnamese water puppetry and broad Australian theatrical humour from rough young performers in a wobbly exchange of cultural icons—pagodas and opera houses, water buffaloes and sharks, rice paddies and beaches, work and leisure. Rural Vietnam and urban Australia? Well, despite a questionable mix of forms and images, there were sufficient links (water for fun, danger, food, passage), and the show engaged its audience, if in fits and starts—what were all those people doing tableauxing in those masks (some of them commedia) at a barbecue? It was at its best when the theatricality of the two idioms intersected: a beautiful golden kangaroo tourist snapping Vietnamese delta life; live performers in the water with the puppets; the Australians manipulating their own puppets. Not all of these were done with precision or resolved choreography, but they suggested the possibility of a richer collaboration at another time. Keith Gallasch

Laurie Anderson, The Speed of Darkness

For many, this was a sublime event, an intimate evening with a chatty Laurie Anderson. I was one of the pleasured. Almost. The sound was excellent, Anderson was relaxed, reading her text from her music stand, playing keyboards, adjusting the volume and a bit of the mix on the sound desk to her left, occasionally fetching her violin (big, loud, dark, Eastern European chords) and lit for listening (too dark for many to see the face they wanted to connect with). ‘Chatty’ is not quite right, ‘discursive’ yes. For one whose songs have an appeal born of brevity and an enigmatic turn of phrase, this was a discursive, often literal-minded Laurie Anderson. Mind you, some stories and observations could end unsignalled and you’d find yourself in the next one. Even so, discursive. And there’s something that happens when the masters of brevity elaborate, the hitherto buried moralist is suddenly and surprisingly at your ear. Her anxiety pieces about the new media came out a little too pat, a little to under-considered and were greeted here and there complacently. However, there were enough moments when a dialectical twist would be applied and you’d think, yes, this is the Laurie we know, she’s just turned us on our heads; or a passing reference to, say, her father’s death would hint at something almost too intimate behind this mask of a singing voice. Keith Gallasch

Denise Stoklos in Mary Stuart

Denise Stoklos, Mary Stuart and Casa

In a Festival where Laurie Anderson playfully recanted and Molissa Fenley reverted meditatively to modernism, Denise Stoklos was right at home with her “essential” theatre—tights, bare stage, single wooden chair, bits of Marcel Marceau mime business—leaving us scratching for words to describe what it was she was doing up there and why we liked it so much. Denise Stoklos provided one of the festival hits though by no means an easy night at the theatre. This was performance in which the physical and vocal worked sometimes exhaustingly in tandem. She is a virtuosic performer and writer. Her body and voice are so finely tuned that you have the impression of a woman passionately articulating every part of herself. In Mary Stuart she plays Mary Queen of Scots as well as her tormenter Elizabeth I using a dexterous physical shorthand and a detailed vocal text. Elizabeth is conveyed in a set of haughty poses and curt phrases while Mary rambles feverishly in her confinement, desperately composing letters to her unforgiving cousin. At the same time Stoklos runs a commentary on her own performance, repeating phrases and physical refrains, constantly elaborating the story for herself and the audience. If this commentary seems sometimes a bit obviously meta-theatricky, it’s at its most effective in moments where the performer appears to be struggling with the physical act of speech. Suddenly she is struck by a word, repeating it, rolling it round in her mouth, exaggerating it until it takes over her body, winding up in her highly articulate toes. Even her hair is passionate! At one point she appears to vomit her resonant voice up from her belly into her mouth. Then, after all that, in one quiet, parting reference to the struggles for power in her home country of Brazil, she changes the audience’s point of reference, turns us on our heads and leaves the stage.

RealTime issue #17 Feb-March 1997 pg. 6-8