Objectillogica: a modern wunderkammer, curated by Megan Schlipalius, is an exhibition based on the cabinet of curiosity fetish of the past. This exhibition is thematically anchored in Eurocentric history but looks to the more recent past of Australia’s colonisation and the curiosities of the Holmes à Court collection, presented at Vasse Felix winery, a striking piece of architecture in the rambling countryside of Margaret River. Paintings and objects are clustered across the walls, sculptures adorn the floor and several glass-fronted, custom-built cabinets house a diversity of treasures, from carved animals to woven hair and feathers and bronze sculptures.

The Wunderkammer of the 16th to the 18th centuries was a prodigious source of inspiration for the noble classes. It was a way of knowing the world, an expression of power, as though the collections of taxidermied animals, fossils, relics, shells, artworks and other artefacts could offer a portal into far flung exotic places. It was also an early expression of colonial ideology. As writer Ian McLean observed in 2010, “The taxonomies displayed in its rooms and cabinets were imagined as micro-scenes of the world. They are amongst the first fruits of a new world founded on European colonial expansion and mercantile acumen of global reach, and signal a burgeoning desire to not just re-order the cosmos but to know, own and control it.”

As such, the Wunderkammer was also an early expression of Enlightenment thinking. It projected forwards, as much as it looked back to the past through the collection of ancient objects. Today there are contradictions inherent within the idea of the Wunderkammer, for while it was once taken so seriously, as a method of categorising, understanding and containing otherness, it is presently viewed as an odd and whimsical pastime for those who had too much time on their hands. In another guise it has also infiltrated contemporary art and Wunderkammering, a term dubbed by McLean, is a curatorial and artistic strategy of mixing, matching and clashing together objects from different times. It fits well within a postmodern and post-colonial logic and over the past decade there has been something of a revival of Wunderkammer exhibitions and their critical evaluation within the Australian context, including Curious Colony: a Twenty First Century Wunderkammer at Newcastle Regional Gallery in 2010 and Wunderkammer: The strange and the curious, at UQ Art Museum in 2015.

Installation shot of Objectillogica, photo by Megan Schlipalius

Sourced entirely from the Holmes à Court private collection, Objectillogica subtly unfolds and brings together a selection of Indigenous, non-indigenous, colonial and contemporary works dating from 300BC to 2014. Despite the Wunderkammer originally being a kind of proto-museum of contemporary museums, Schlipalius told me by email that “the arrangement of works was mainly inspired by the notion of an anti-museum. This approach was initially inspired by MONA’s Theatre of the World — although at a much more modest scale! I attempted to put disparate objects next to each other while creating a visual balance throughout the cabinets.” The MONA connection is significant, as David Walsh’s institution is also founded on antagonism to the usual museological conventions of display and curation.

Likewise, Objectillogica is an anti-museum in that it eschews the traditional taxonomic systems of museums and early curiosity cabinets. This exhibition is also in tension with the minimalist hangs of many contemporary art displays, instead pushing to fill all available space and, rather than being arranged according to similitude or taxonomic rigidity, there are thematic currents running through the show that make it compelling as well as cohesive. What is taken from MONA’s Theatre of the World is the Wunderkammering approach of mixing ancient, modern and contemporary, artefact and art and, rather than drawing from all reaches of the globe, it is largely located in the Australian and primarily Western Australian contexts.

Unknown artists from the Kimberley region, Egypt and Papua New Guinea, photo by Robert Frith, Acorn Photography

The show considers a specifically Australian ‘wonder,’ where it is apparent that the collecting process, by Holmes à Court, has been driven by a keen eye for the historically significant, culturally relevant and occasionally obscure. There are exquisite works of art on display here and the obscure has been brought to the forefront in keeping with the traditional Wunderkammer, as a way to reveal and revel in the curious. At the entrance is a linocut by Rew Hanks titled The Hunter and the Collector. It features botanist Joseph Banks surrounded by a plethora of objects that relate specifically to Banks, such as Banksia flowers, May Gibbs’ wicked Banksia Men and the prickly pear weed introduced by Banks. At his feet is an image of the jar containing the head of Pemulwuy, the Indigenous warrior resistant to colonisation whose head was reportedly sent to Banks in England. This image critiques colonial attitudes and makes evident the damage wreaked on ‘new worlds.’

This is where the relevance lies in presenting a Modern Australian Wunderkammer. Like a transhistorical lesson, it offers ways to rethink events of the past and reconsider our place in the world; there is revelatory strength in mixing old and new. This makes it serious business, with biting political commentary, but there are also currents of humour running through this interpretation. There is the obligatory crocodile, in this case Francella Tungaltalum’s Yirrikapai (The Saltwater Crocodile), in a nod to museological tradition. There is a toolkit made entirely of extruded plastic by the artist Eamon O’Toole. The Wunderkammer presented here is still a way of knowing the world, of teasing out the idiosyncrasies of the local and national context with all its inherent layers of meaning and playfulness.

–

Objectillogica – a modern wunderkammer, curator Megan Schlipalius, Holmes à Court Gallery at Vasse Felix, Cowaramup, WA, 21 May-1 Oct

Top image credit: Danie Mellor, Hunter Gatherer, 2008, mixed media with shopping trolley, image courtesy the artist

“We live in a world where there are big films like Alien: Covenant that shine a light into and explain the darkness,” Revelation Perth International Film Festival Program Director Jack Sargeant told RealTime in the lead-up to the festival’s program launch last week. “I grew up with horror films where you didn’t explain the darkness. I find the cultural desire to explain everything really depressing.”

Since its inception in 1997 by founder Richard Sowada, Revelation has maintained a commitment to delineating a space for watching and discussing daring works of independent cinema in counterpoint to the mainstream cinema market. Now, with the festival approaching its 2017 instalment, 6-19 July, both the social and cinema worlds have grown ever-more conservative and difficult to comprehend.

For Sargeant, cinema offers something less than instructive and more interpretive — a place of strange images, sounds and narratives even more fantastical than the real world oddities of President Donald Trump’s tweets, alternative facts and unwinnable wars. “Explaining a truth is overrated in film,” says Sargeant. “I quite like films where nothing is explained. There’s a pleasure in not having a reading of everything.”

Richard Sowada and Jack Sargeant

This approach has produced an eclectic collection of films for the 2017 festival that are “from all kinds of worlds,” and which don’t direct the viewer on how to think. The program encircles what Sargeant calls “weird indie films,” art-house dramas, music and art documentaries, queer films, horror films and children’s films. As well as the continuation of the festival’s academic conference sidebar, there’s “an event called Revel8 that is all about Super 8 film and Super 8 filmmakers; so we have a real love of the living culture of film as a physical medium.”

“All these different kinds of cinema matter,” says Sargeant, despite the fact that most of the films aren’t securing general releases beyond the festival circuit. Notwithstanding their divergences in genre and subject matter, the films Sowada and Sargeant have programmed share the quality of both expressing and contextualising today’s strange feeling of global confusion, and of being part of the “whole world of filmmakers not getting noticed,” despite the popularity and abundance of film festivals.

Women Who Kill

The collision of the horror genre with queer themes is another often-unnoticed realm. Though a highlight of Sydney’s Mardi Gras Film Festival earlier this year, Women Who Kill (2016), will not be securing a general cinema release. Sargeant describes this brilliantly architectured genre film, by debut filmmaker and web-series comedian Ingrid Jungermann, as revelling in “lesbian camp and deadpan” humour. Jungermann’s Morgan is a true-crime podcaster whose rampant commitment-phobia leads her to believe that her new girlfriend, Simone, is not just an eccentric, fallible human but a sociopathic murderer. The film’s central conceit of fear of relationships is transformed into literal horror, the conventions of crime-mystery and slasher films deftly adopted to insert the viewer into Morgan’s paranoid inner world as it grows impossible to know if her fears are real or imagined.

Another curatorial focus is a stream of films in the quasi-documentary mode between fact and fiction. “We live in an era of fake news and virtual existence. I think these hybrid documentary/fiction films expose that,” says Sargeant.” But they also expose our desire for it. It’s that psychological thing of wanting our own confusion to be contextualised. Everything is sort of baffling and strange, and I really want to see films about bafflement. Confusion is a good thing.”

Houston We Have a Problem

The internationally co-produced docufiction, Houston We Have a Problem (Žiga Virc, 2016), runs in this vein. “It’s about the relationship between the USA and Yugoslavia in the space race in the 1960s,” says Sargeant. “It has philosopher Slavoj Žižek in it saying ‘Even if it didn’t happen, it’s true!’ It’s hilarious, with all the touchstones of hybrid documentary cinema today.”

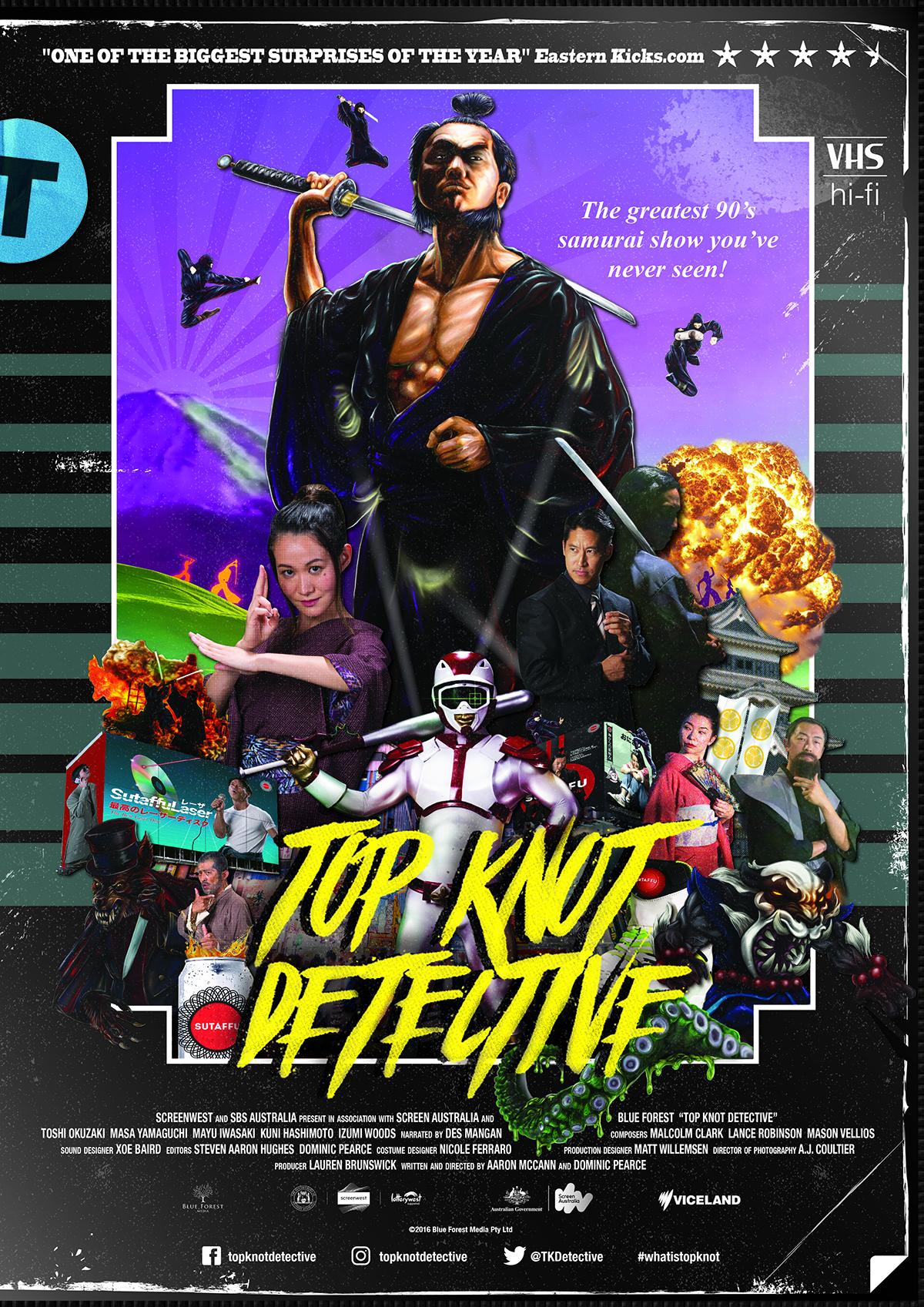

Top Knot Detective

Top Knot Detective

The Western Australian film Top Knot Detective (Aaron McCann and Dominic Pearce, 2016) deploys the mockumentary format to present an homage to “an imaginary cult TV show, and they interview everyone involved in it. You would not know that the TV show is not a thing. It really plays on the audience’s collective experiences and shared cultural memories about half-remembered late night TV. It’s very funny.”

“There is a real sense that both narrative fiction and documentary film aren’t quite enough anymore…[hybrid documentaries] are about how we create, construct, view and examine myth and history. They are just one of the edges of the program, but there are lots of edges.”

A home for the slow-burn film

In its 20th year, Revelation functions at an ironic edge of the film industry, too. The increasingly franchise-soaked film market has led to a growing conservatism and monopolisation of both mainstream and arthouse cinema programming, which has partly led to the space for film festivals to grow and nurture small films squeezed out of general release in cinemas. As such, Sargeant sees Revelation as a unique space in Perth for slow-burn films at the edge of film culture to get a big-screen life.

Cinema: the group experience

Despite the attractions of video-on-demand and home entertainment, “people want to watch films on the big screen,” says Sargeant. “Contrary to popular belief, they don’t just want to watch them on TV. The big screen spectacle is what cinema is all about, the communal experience. My go-to is always Rocky Horror Picture Show. You can’t dance to that by yourself at home. In the cinema it makes sense. When you watch a horror film, you need to be around 200 people. When you’re watching a romance, you want to be crying with everyone. Cinema’s a group experience, and that’s key to our pleasure of cinema.

“There’s a film festival every day of the week. But they all have their own energy and their own identity. Revelation has its own energy. We’re all film nerds, we’re all fans. We have academics and non-academics who are experts in their area. We’re not snobby. I’m not really interested in good film taste. I’m interested in all the different types of culture — music, art — and that feeds into the programming.”

–

Revelation Perth International Film Festival 2017, festival director Richard Sowada, program director Jack Sargeant, Luna Palace, Leederville, Perth, 6-19 July

Top image credit: Women Who Kill

The influence and the legacy of Roger Smalley (1943-2015) are somewhat legendary in Western Australian new music circles. Having emigrated from his European home to Perth in the early 1970s, Smalley spent over 30 years teaching composition at UWA before retiring in 2007; consequently many of his former students now hold senior positions in Western Australian universities and ensembles. As a young composer myself I feel his influence in many ways, despite having never actually met him, since nearly all of my teachers received his tutelage in some form. A notable ex-student is Cat Hope, Artistic Director of Decibel New Music Ensemble, a superstar of Australian new music and curator of Intermodulations, a recent concert in Smalley’s memory featured in TURA’s Scale Variable series.

In pre-show interviews and at the concert, Hope made a point of explaining how Smalley felt his early music inappropriate for Australian audiences, whose distance from the European scene and general inexperience with new music had cultivated a fear of the unknown and relative distaste for electronic music. This concert was, by and large, dedicated to those early European works, which Hope is adamant today’s Perth audience will enjoy—largely due to Smalley’s lasting legacy. She’s not wrong.

Decibel’s concert comprised four smaller chamber works in the first half featuring members of the ensemble in various iterations, and one large-scale work for ensemble and electronics in the second, for which the full ensemble assembled.

First up was Didjeridu (1974), an electroacoustic work for four-channel tape of samples of Australian Indigenous music from the Mornington Peninsula. The characteristic sound of the didjeridu is at first distinct, but gradually distorted beyond recognition, an unconscious—or was it conscious?—comment on the atrocious treatment by whites of Indigenous culture. Appropriating Aboriginal music for a European electro-acoustic work is at best kitsch and at worst racially insensitive. Today composers understand this (mostly) but in previous decades it was hugely popular, an exciting way to combine different musical styles. Doubtless Decibel leader Cat Hope isn’t blind to this, the work functioning more as a window into the past of Australian composition than as contemporary social comment.

Decibel Ensemble, Scale — Variable, Tura New Music, photo Bohdan Warchomij

Two works for piano and electronics follow: Transformation (1968, revised 1971) and Monody (1971-2). Both use the same electronic technique (ring modulation) to extend the colour palette of the piano and, although composed around the same time, they really sound nothing alike. Transformation is virtuosic and grand, featuring drawn-out sweeps and glissandi and fierce bass notes drawing as much colour as possible from the full range of the piano. It’s almost exhausting to watch guest artist Adam Pinto perform with such depth, from the most intense hammering sounds to suddenly subdued, glassy chords. If this piece is excessive, the second is refined, featuring a sole one-note melody throughout. It’s still extremely technically demanding on the performer but in a different way, as they must play piano with the right hand and control the sine wave frequency with the left, occasionally also moving to triangles and congas. The use of ring modulation in this piece is more melodic and seems to play a more active structural role than in the first. The tonal palette of the composition is unique, almost quirky, as many of the combined frequencies of piano and sine wave don’t conform to equal temperament.

We also hear Impulses (1986), an acoustic work for chamber sextet. This is a rhythmically driven conglomeration of sounds in which percussionist Louise Devenish and cellist Tristen Parr shine as the most assertive performers.

Decibel saves the best for last, assembling onstage to perform the 45-minute-long Zeitebenen. This unique and charismatic work, premiered in Germany in 1973 by Smalley’s new music ensemble Intermodulation, has never been performed in Australia until now, the score spending the past 40 years collecting dust somewhere in the University of New South Wales. It’s immediately obvious that this work draws on influences from each of the four smaller pieces performed earlier, sharing melody with Monody and recalling the electronic soundscape of Didjeridu. Here Smalley’s ideas are given the space they need to be completely aired. The work is politically charged, featuring sounds of warfare alongside those of children, storms, car horns, seagulls and whistles and, at one point, alluding to Tibetan throat singing and featuring colourful conversations between viola, clarinet, vibraphone and piano. This strikingly imaginative piece ends with a definitive thud from Devenish’s bass drum.

Intermodulations was extremely well-received by Perth’s new music audience. The resounding takeaway message was this: let’s not allow Roger Smalley’s music to be forgotten, as has happened to the compositions of so many Australian composers of his generation.

–

Tura New Music, Scale Variable: Intermodulations, Decibel New Music Ensemble; State Theatre, Centre Studio Underground, Perth, 7 June

Perth-based composer Alex Turley’s City of Ghosts was performed by the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in the 2016 Metropolis New Music Festival. He was a RealTime-mentored music reviewer at Perth’s 2015 Totally Huge New Music Festival.