First, an organ, a dark sacred warbling juxtaposed with an ominously modern buzzing. In the dark, a dazzling down-light illuminates a lone knight in shining armour refracting blues, flashing silver. The world brightens to grey, the colour sucked out. Her armour removed, a young woman, Joan of Arc (Sarah Snook), sits silent, expressionless in an abstracted evocation of the ground level interior of an intimidatingly huge mediaeval castle tower, its high semi-circling wall comprising long, seemingly soft, narrow strips of grey cloth, the hard floor lightened with the sheen of polished concrete, each aspect of this place a coherent melding of architectural past and present, hauntingly illuminated from a narrow palette of muted greys, blues and greens.

Likewise, the costuming of Joan’s male interrogators, all in black, evokes chic Edwardian elegance while appearing fashionably current, including French knight Bluebeard’s stylish folds, otherwise not out of place in a Velasquez painting. Joan’s attire however is markedly modern, soft, grey and white, as if exercise-ready. She’s at first glance a 21st century woman. She is anything but.

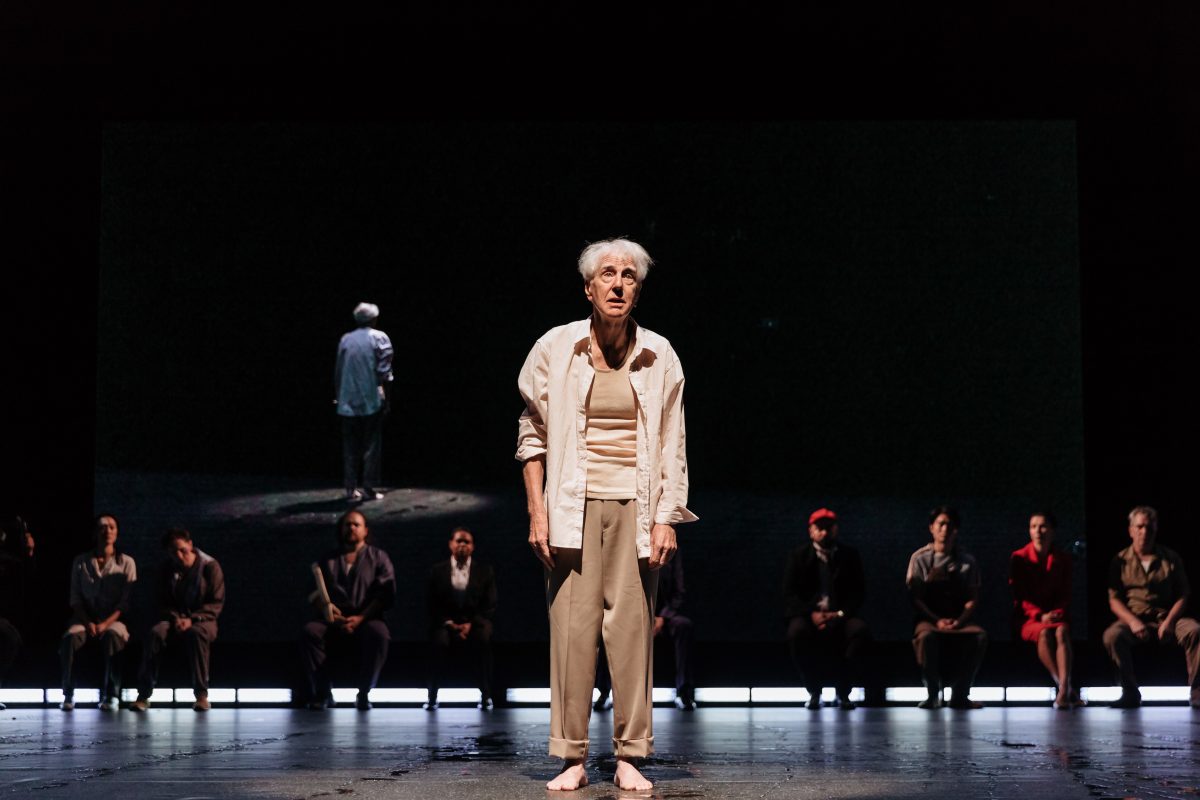

In director-writer Imara Savage’s shuffling of scenes from George Bernard Shaw’s St Joan (1923), she opens with his fourth, staged effectively as the first of a series of arraignment and trial scenes which provide the production’s core. Here Joan sits in silence while the English and French authorities engage in testy debate, with clever sparring between Bill Zappa as a sharp Jesuitical Bishop of the Holy Roman Empire and David Whitney as the blunt Earl of Warwick. The production’s other scenes are realised as interpolated flashbacks: edited key moments from Shaw and new scenes by Savage and playwright Emme Hoy in which Joan communicates with her voices — St Margaret, St Catherine and the Archangel Michael.

The English want Joan dead, the French clergy for her to repent and be saved. But they do find common ground for their prosecution — each has much to lose. Joan’s vision challenges the authority of the Holy Roman Empire with both heresy and nationalism, while for the British (nationalism they like) it eliminates the feudal aristocracy from the chain of command between God and King, on the one hand, and, on the other, Joan and the people. We sense already that Joan’s fate is sealed, with even the seeding of the final rationale for her execution — heresy. The positioning of the scene is a clever move by Savage, establishing a thematic framework and underlining Joan’s inevitable helplessness. The same group of men will appear in the end in a semi-circle around her, delivering to us as much as to Joan their pulsing litany of reckoning.

When it comes to the fraught mediaeval notion of the divine right of kings Joan is an absolutist; not for her the subtleties of power, hierarchy and religious law. These she can ignore with tunnel vision purpose that first wins the day — her successful lifting of the seige of Orléans and enabling the coronation of the Dauphin — but then loses the war with her failed siege of Paris and subsequent capture. In her unwavering support of the monarchy — absolute, masculine — Joan is no feminist (and in France a hero of the left and right), but nonetheless Shaw, an ardent feminist, and moreso Savage and Hoy see Joan’s life as the tragedy of a lone, powerful idealist destroyed by male pragmatists.

The ingredients are apt and plentiful, Shaw’s Inquisitor grumpily foreseeing the unfolding of a Greek tragedy. Joan’s rapid rise to power is countered with her equally rapid fall to defeat in war, her profound vulnerability in the face of torture and a sudden loss of faith when deserted by the voices of saints whose predictions were not realised. The latter is a wrenching, pivotal moment in Shaw’s play, as it is in this production, when Joan’s sheer aloneness (pinpointed by her accusers) and fear of pain compels her to sign a confession, only to tear it up when she is told she will be forgiven but imprisoned forever. Once more her spirit soars defiantly, but now with a rare, flowing poetry evoking all that she will lose:

“I could let the banners and the trumpets and the knights and soldiers pass me and leave me as they leave the other women, if only I could still hear the wind in the trees, the larks in the sunshine, the young lambs crying through the healthy frost, and the blessed church bells that send my angel voices floating to me on the wind. But without these things, I cannot live …”

Joan’s sudden shifts of mood and temper, from flailing depression to spirited anger, are realised by Sarah Snook with wrenching acuity and lucidity, revealing the complexities of Joan’s embrace of her fate — to die in fire, despite her voices having told her she would not, but maintaining her faith with fervour. The sense of tragedy is given even greater weight by Joan’s hubris; though ever denying vanity, she brooks no contradiction, however well-reasoned, for herself, her voices and her unwise military strategy.

Savage’s ambition is to transform Shaw’s St Joan into a full-blown tragedy in the great tradition. She senses one in Shaw, but his subject is often more argued about than seen and we sense little of Joan’s voices. Savage has felt compelled to grant herself and co-writer Emme Hoy licence to shear away great swathes of Shaw and run with the poet in Joan, drawing on a variety of historical and other sources. In these eerie moments, the dark closing in with an intense blue around an awed Joan, Max Lyandvert’s score elevates the sense of mystery, sadly beautiful with melodic harp and strings in a moment in which Joan expresses her great fear of pain, contrasting with the recurrent slow, grim bell-tolling that frames the interrogation scenes (ironically she tells her General —Brandon McClelland — that it’s in the sound of bells that she hears her voices).

Snook’s possessed Joan speaks in her own voice as both herself and her saints. With a cruel litany-like insistence, the voices demand she recall returning to her empty family home to find the footprints of enemy soldiers who might have even touched her bed. The sense of personal invasion is palpable. The enigmatic question the voices repeatedly pose, “Are you an empty house, or a burning house?” commences here and is iterated to the very end of the play. Elsewhere Joan argues anxiously with the voices, desperately doubting her capacity to lead, to fight, to succeed.

If Shaw deftly created a Joan who seems to be part divine fool — a logic-bending scourge of political and religious convention — and part plain-speaking, enthusiastic youngster, Savage and Hoy allow Snook to bracingly embody her possession, cross-legged, rocking, eyes closed, hands clapped to ears, or engaging wide-eyed with her saints, her voice lyrically transcendent. She is more complex, more believable if stranger than Shaw’s Joan and undeniably tragic.

Snook and fellow performers comprise a taut ensemble, the characters’ antagonisms contained for the most part by a quasi-formal courtliness in diction and movement. Any exception stands out — Joan in every respect, Gareth Davies’ pragmatic Dauphin with his run-on whingeing and slumped posture, and the English Priest’s (Sean O’Shea) rabid testing of decorum in debate and effective prosecution with his 56 ridiculous claims against Joan, reduced by John Gaden’s coolly practical Inquisitor to 12. There are frequent pointedly humorous moments like the Priest’s claim, “No Englishman is ever fairly beaten” and his irritation that Joan’s voices don’t speak in English.

Gareth Davies, Sean O’Shea, David Whitney, Brandon McClelland and Sarah Snook in Sydney Theatre Company’s Saint Joan, photo © Brett Boardman

As often with adaptations, the cut and pasting of original and additional material can at times lose a production its sense of cohesion. Those unfamiliar with Shaw’s play with its epic expositions and relatively straightforward narrative might be hard-pressed to clearly grasp Joan’s story in this version. Among other things, her defeat at Paris is glossed over and the merging of the General Dunois and Joan’s soldier ally (Jack in Shaw’s play) into one character results in his inexplicably abrupt turning against her. And I didn’t know what to make of Snook’s Joan seated clutching her side in the last trial scene, as if perhaps wounded. If performed in full, Shaw’s play can run to three hours; this version comes in at 110 minutes and could benefit from a little more detail from the original including what precisely enthralled her followers. At moments the production has a rather peremptory feel, for example when Joan shortens her hair, and even in the staging of the production’s final image, which — going into metaphorical overdrive — abruptly if strikingly declares that Joan’s fate is solely in her own hands. Despite these hesitations, overall the rhythm of the production’s alternation of three timelines — arraignment and trial; earlier events; Joan’s encounters with her voices — is deeply engaging and rich with further potential.

This Saint Joan is not Shaw’s, although advertised as such. It’s an insightful adaptation, a powerful convincing standalone work finely directed, written and designed and blessed with Sarah Snook’s account of a Joan who is by turns heroic, proud and truthful, doubting, confused and agonisingly distraught, and finally, defiantly tragic. Imara Savage writes in her program note, “We want to show a young woman who is flawed but filled with conviction to the very end, someone who insists on living on her own terms, no matter the cost.”

In the abstract this is fine, but as Savage asks earlier, “How is Joan a hero if we take both her religious fundamentalism and her nationalism seriously?” Which we have to. The advantage of the Savage-Hoy-Snook Joan is that she embodies more otherness than Shaw’s and is not simply reducible to 21st century individualism or idealised feminism. She is stranger than that, and better for it.

–

Sydney Theatre Company, Saint Joan, writers George Bernard Shaw, Imara Savage, Emme Hoy, director Imara Savage, performers Gareth Davies, John Gaden, Brandon McClelland, Sean O’Shea, Socratis Otto, Sarah Snook, Anthony Taufa, David Whitney, William Zappa, set designer David Fleischer, costume designer Renée Mulder, lighting designer Nick Schlieper, composer, sound designer Max Lyandvert; Roslyn Packer Theatre, Sydney, 9-30 June

Top image credit: Sarah Snook, Sydney Theatre Company’s Saint Joan, photo © Brett Boardman

An ironically irresistible Hugo Weaving stars in Kip Williams’ thrillingly propulsive, politically gripping production for the STC of Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, an unnervingly funny, relentlessly incisive parable of a thug-cum-demagogue rising to absolute power. He achieves it with the complicity of a corrupt politician in an all too familiar “infrastructure government” in league with a green grocery cartel. They quickly lose control of their gangster agent of change (whose initial goal is control of the vegetable market), then the courts, the press and ultimately the democracy they have hitherto expertly manipulated.

Though casually evoking 1930s Chicago and the gangster movies that inspired Brecht, director Kip Williams and translator Tom Wright infuse the production with a sense of our own troubled times via an artfully choreographed interplay of stage performance and live video feed with drolly deft deployment of the clichéd and distorting language of Australian and international politics and economics. The effect is to render contiguous the 30s rise of fascism and the current illiberal push to the right in modern democracies. Past and present become chillingly inseparable.

This world (designer Robert Cousins) is realised within a capacious studio with open dressing and green room spaces to either side and a huge upstage screen fed by a busy camera team working initially in movie-making mode and subsequently, as politics turns overtly criminal, delivering with television news urgency, intrusive vérité shooting and propagandistic pomposity. It’s not a simple trajectory: in a funeral scene late in the work there’s a highly effective return to an intimate cinematic vision, at once compelling but perhaps also mockingly arthouse.

Dressed and masked in black, the camera crew moves about unobtrusively, the numerous set-ups with actors seamlessly realised and the tracking trajectories marvellously patterned so that Kip Williams’ direction and Justine Kerrigan’s cinematography is realised as a swirling dance of cameras and actors. The director’s well-known choreographic-cum-cinematic facility is frequently evident, for example when Ui threatens the politician Dogsborough (Peter Carroll). The latter is seated downstage, back to us, facing Ui who delivers his intimidating spiel moving on and about an axis between his victim and the screen on which we see Dogsborough writ large in anxious profile. It’s a perfect fusion of stage and screen, heightened by Weaving’s cajoling ‘dance,’ exploiting oscillation between safe distance and threatening proximity. As ever, the actor moves with great verve, from an initial pugnacious, prowling swagger to the elegant, confident stride of the demagogue. When one of his gang earlier dares to suggest how he might present himself, Ui retorts, “What the hell is ‘natural’?” Unfortunately for his victims, Ui is, in another sense, a natural, and a quick learner.

True to Brecht’s wishes, the makers admirably avoid the literalising of Ui, whether as Hitler or any other demagogue, such as Donald Trump. There is however an hilarious lesson in Hitler-ish posturing — desultorily taught by a campy failed actor (Mitchell Butel) — and a brilliant one-off sight gag involving Ui toying with but dismissing the fascist leader’s moustache and hair style. Weaving’s Ui is utterly his own man, one with limited intelligence but blessed with tunnel vision and escalating narcissistic self-belief, incanting a narrative of heroic emergence melded with paranoia. This is realised brilliantly in Brecht’s echoing of Shakespeare’s Richard III in a confrontation between Ui and Betty Dullfeet (Anita Hegh), the combative wife of the newspaper publisher Ui has had murdered.

As rain falls steadily on the funeral gathering, Ui delivers a seemingly sincere self-account, impassioned and highly convincing, replete with cosmic metaphors, bewildering an angry but vulnerable woman suddenly confronted with the unexpected. As the staging reveals the scope of the gloomy, black umbrella-ed funeral, the screen close-ups of Ui and Dullfeet provide a cinematic intensity, yielding one of the few moments of heightened realism in the production if shot with a wry arthouse verve. Weaving invests all his considerable craft in the scene, the closest we get to empathising with Ui, momentarily understanding the depth of his self-belief, however fantastical, and in himself as a performer. When we next see Ui, he is a fully realised, coolly intimidating demagogue, terrorising a vast (cinematically multiplied) public into voting for him.

Colin Moody, Hugo Weaving (background), Hugo Weaving, Ursula Yovich and Brent Hill (foreground), The Resistable Rise of Arturo Ui, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Daniel Boud

With Brecht’s hyperbolic text and a production excelling at the playwright’s notion of distanciation, the funeral scene is a thrilling disruption, as are the scenes in which Peter Carroll’s Dogsborough is granted a palpably intimate presence. In part driven to corruption by the need to support a son with a disability and by Ui’s thinly veiled threats directed at the child, the politician becomes increasingly guilt-ridden, creating a moral counterpoint to Ui’s career, strongly felt in a scene in which Dogsborough quietly ponders his crime and Ui’s rise while face to face with himself in a dressing room mirror, one of a number of mirror images in the production that query the nature of performance of the self.

Another scene tellingly focused on the face has Ui’s gang members spread about the stage bitterly challenging each other while a camera operator peers up between the boss’s knees. Weaving is slouched in a lounge chair, Ui’s usually hyper-animated features shut down, his heavy brow creased with introspection as he nibbles from a packet of Nobby’s Nuts. The close-up stillness exudes danger as much as comedy, indicative of a new stage in Ui’s rise, a contemplative prelude to murderously taking firm control of his own immediate realm.

Williams’ production busily fills the stage with evolving political ferment, first evident in a Senate-type enquiry scene (with Anita Hegh doing a Michaelia Cash microphone grab) overseen by Arturo Ui (think President Donald Trump’s destructive appointment of Scott Pruitt as Environmental Protection Agency Administrator). Later, a courtroom trial turns to farce as Ui’s thugs take control. Staged as a series of brief scenes punctuated with a repeated dance of pulsing spotlights as the performers reconfigure, it’s rich in comic detail, including Peter Carroll as an enthusiastic female courtroom stenographer rendered deliriously helpless as characters and cameras swirl about her.

Peter Carroll and cast of The Resistable Rise of Arturo Ui, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Daniel Boud

Throughout, Brecht’s rich language is inflected with familiar contemporary utterances: “with respect, you’re not listening,” Joe Hockey’s “leaners, not lifters,” Ui’s plagiarising of the lyrics of John Farnham’s “You’re the Voice,” and much more — “slush funds,” “positive mindsets,” and a green grocery variation on John Howard’s “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances under which they come.” And then there’s the fun of invention: “Even the gravy train finds itself stopping at honest stations.” The apparent silliness in the recurrence of the names of vegetables — cabbage, cauliflower, kohlrabi — in a political scenario gets continued laughs but also underlines the banality of corruption and an everyday route to power, and profit — think Coles and Woolworths’ relentless manipulation of what they pay dairy, fruit and vegetable producers.

Williams’ performers, often in multiple roles, create strongly etched characters including Ui’s gang members: Roma (Colin Moody), Giri (Ivan Donato) and Givola (Ursula Yovich). Stefan Gregory’s bracing compositions, with recurrent driving drumming and a film-noirish gravitas sound gives over to Wagner at a critical moment and a melancholy wordless chorale at another. An affecting harp piece underlines the apparent idyll of Givola’s florist shop in which Betty Dullfleet’s husband’s throat is cut by the owner. This setting is one of the few instances in the production where spectacle, multiple long strands of flowers luxuriously filling the stage, supersedes distanciation, if meeting the challenge of Brecht’s construction of the scene with two pairs of characters, oblivious to each other, wandering the shop. Another superfluity is the use of projected animated drawings — a row of poplars, a burning market building, a woman in a street. Elsewhere the production, including its deft use of intertitles, is tightly conceived and executed.

Ui’s chilling speech to the masses at the play’s end recalls Donald Trump’s dark account of the state of America in his inauguration speech. Ui spells out a vision of human savagery against which he will defend the people (dissidents are meanwhile casually shot) while offering them freedom of choice. Ui’s cool, formulaic manner recalls Betty Dullflet’s earlier defiant charge that Ui is “a meat machine trying to believe it has a self.” Now she stands beside him, defeated. The chaotic dance that prefigured Ui’s ascension is over, resolved into fascist order, overseen by a man who had declared to Betty, “I am a fanatic – I have faith.”

Our own liberal democracy is under less corrosive threat than that depicted in Brecht’s parable, and is therefore easy to underestimate or ignore, while in Turkey and the newer democracies of Eastern Europe human rights are rapidly eroding. It’s surprising and fascinating that an emerging wing of the American Democrats is the defiantly titled Democratic Socialists of America. In Australia’s parliament, we have proliferating right wing party representatives, a conservative often reactionary Coalition government and a Labor Party largely driven by its right wing. How long will it be before a defiant assertion of democratic socialism emerges in Australia to defend and build on public utilities and rights? Better that than a slow dance to death. But it is resistible.

–

Sydney Theatre Company, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, writer Bertolt Brecht, translator Tom Wright, director Kip Williams, performers Mitchell Butel, Peter Carroll, Tony Cogin, Ivan Donato, Anita Hegh, Brent Hill, Colin Moody, Monica Sayers, Hugo Weaving, Charles Wu, Ursula Yovich, set designer Robert Cousins, costume designer Marg Horwell, lighting designer Nick Schlieper, composer, sound designer Stefan Gregory, cinematographer Justine Kerrigan; Roslyn Packer Theatre, Sydney, 21 March-28 April

Top image credit: Anita Hegh, Hugo Weaving, The Resistable Rise of Arturo Ui, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Daniel Boud

Thai-Australian playwright Disapol Savetsila’s Australian Graffiti has its moments: flashes of crisp, acerbic dialogue, grim physical comedy, occasional deft character delineation, vivid arguments and some emotionally sensitive exchanges. It’s otherwise underdone — character development is limited, critical motivation unexamined and the tonal shifts in language and mood between the scenes with and without a ghost character are minimal in the play’s easy-going naturalism, despite a press release claim for its “magical realism.” For real magic you need to turn to Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, winner of the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, in which ghosts can slip in and out of the world with unnerving effect.

Faults aside, Australian Graffiti warrants attention since Savetsila is another in a number of new culturally diverse voices coming to Australian stages and performance spaces and needs to be heard, not least for the essentially dark vision entailed in his story of Thai-Australian business failure compounded by Australian racism and traditional Thai attitudes to filial duty. For all of its leavening comic moments, the play offers at its end only a sliver of hope for cross-cultural conciliation.

Mason Phoumirath, Airlie Dodds, Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

Amiable chef Loong (Srisacd Sacdpraseuth) has died — his body heartlessly lugged about by the play’s other characters in bouts of black comedy — but visits as a ghost, encouraging those who listen that there is life beyond a failing Thai restaurant in a regional Australian town. The elegantly dictatorial Baa (Gabrielle Chan) continues to run the business with a ruthless work ethic, regardless of the absence of customers. Illegal immigrants — boisterous, despairing Boi (Kenneth Moraleda) and the more hopeful but ill Nam (Monica Sayers) — have become Loong’s replacements, but are not good cooks (they desperately experiment with Vegemite dumplings). Moving the business from town to town has forced home education and separation from his peers on Baa’s lonely, intelligent adolescent son and waiter Ben (Mason Phoumirath). However, a chance meeting by a creek introduces Ben to Gabby (Airlie Dodds), a caustic, tough-minded white Australian of his own age who introduces him to yabbying. This is where the play opens with youthful banter and marked sexual attraction, although Gabby drolly mocks the idea of a relationship tainted “with the stigma of sweatshop labour.”

There’s a bitter edge to joking in Australian Graffiti. Gabby’s father (Peter Kowitz), a nasty character of the bullying Australian “can’t you take a joke” variety grows angry when humour is directed at him: “You speak good English,” he says to Ben, who retorts, “So do you.”

Ben and Gabby’s meeting at the play’s end will be a test whether or not Ben can continue the relationship with the only friend he has ever made (if barely so) and if Gabby can separate herself from the racism of her policeman father and the townspeople. After their first meeting, she’s been resolutely hostile, feeling — because of Thai graffiti appearing on a church altar wall — that Ben and family have turned her private paradise into a hell. It’s not much of a town, but it’s hers, she declares with passionate conviction in one of the play’s stronger moments. But there’s little to indicate in the course of the play that she’s capable of the insights that come at its end. Ben, more convincingly, is determined to develop the friendship and break free from the restaurant and his mother’s insistence on gratitude for her sacrifices (“I’m building an empire for you!”). A girl and a ghost draw him out of a smothering cocoon which he knows has never been ‘home,’ although the options for him to remain in the town seem profoundly limited as his mother moves on.

Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

The executor of the graffiti is finally revealed and the symbols translated, but the meaning is enigmatic and the motivation behind it left infuriatingly unexplained — an opportunity lost to deepen both a character and the possibility for shared understanding between cultures in conflict. Why might someone be driven to commit such an act? It also prompts the question, why Australian Grafitti? Is it ironic? The graffiti in the play is Thai, it spoils and desecrates, but the disproportionate response (Ben accused, the violence, banishment in effect) and unleashed racism could be seen as graffiti writ large on the immigrant body.

One of the strongest images in the play is of a small girl who is sighted recurrently peering into the restaurant until, with her black eyes, she becomes a frightening apparition for the nervy Boi, racism incarnate. A crowd forms, rocks are hurled, windows broken and we learn later Gabby was one of the perpetrators. Other moments linger: Loong’s enticing Ben to relish the freedom inherent in eating fresh mango and his wise discourse on entrapment with the metaphor of dogs happily fattened up to be eaten: “suicide by food,” he quips. His admission, “All I have is hindsight,” is one the play’s best from Srisacd Sacdpraseuth’s engagingly realised ghost character, who grumpily complains to Nam that when he was dying, her over-vigorous CPR broke a rib. His funeral, after days of lying about and ritually held in the restaurant building for fear of alerting authorities to the presence of illegal immigrants, becomes an aptly incendiary affair for a sower of doubt.

Monica Sayers, Srisacd Sacdpraseuth, Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

Australian Graffiti’s limitations were underlined by a large, high-walled greyish, fluoro-lit set (representing a room adjoining the unseen restaurant) that, although amplifying Ben’s sense of homelessness, reduced the sense of intimacy and entrapment felt in the writing and produced, at times, over-projection from some of the performers (a late reference to the room as a former ballet studio didn’t compensate).

Despite its occasional strengths and strong performances, Australian Graffiti’s appearance on an STC stage was clearly premature. It’s not without promise, but Disapol Savetsila deserves dramaturgy that will address the gaps in the work and opportunities to follow through on the complexities he conjures.

–

Sydney Theatre Company, Australian Graffiti, writer Disapol Savetsila, director Paige Rattray, performers Gabrielle Chan, Airlie Dodds, Peter Kowitz, Kenneth Moraleda, Mason Phoumirath, Srisacd Sacdpraseuth, Monica Sayers, designer David Fleischer, lighting designer Sian James-Holland, composer Max Lyandvert, sound designer Michael Toisuta; Wharf 2, Sydney, 7 July-12 Aug

Top image credit: Australian Graffiti, Sydney Theatre Company, photo Lisa Tomasetti

Nakkiah Lui has appropriated — or been appropriated by — the bourgeois comedy of manners. Tellingly, she doesn’t satirise the form, though now and then tips it into riotous farce, but uniquely centres Black is the New White on a well-to-do Aboriginal middle class family who come to acknowledge that, like their white peers, they can be oppressors of fellow Indigenous Australians and, when it comes to arguing over the black/white divide, they are sometimes their own and each other’s worst enemies. On the surface, Black is the New White is wickedly funny, infused with Aboriginal humour — blunt, droll, barbed — and, for a middle class family, not at all genteel. Its subjects are anxieties about self, love, community, gender and politics, joked about but indicative of a deeper unifying concern about race. That’s not surprising, even for a family like this at a remove from the grimmer aspects of Aboriginal life in Australia. Their insistent joking is more than communal fun; it’s a political weapon and a collective defence mechanism.

For a white Australian audience, Black is the New White offers potential insights into a class of people rarely portrayed on stage or screen, though increasingly in evidence in the professional characters in Redfern Now (2012-13) and scattered roles in a number of Aboriginal plays and television productions. Ray (Tony Briggs), the father in this family and a community leader, fancies himself as an Aboriginal Martin Luther King, wastes time debating the qualities of lettuce types on Twitter, plays golf, objects to his daughter’s relationship with an unemployed white experimental cellist and, when frustrated, hides in a virtual reality helmet (not turned on). And he’s doggedly racist. It’s beyond him to shake the hand of or offer a drink to the inadvertently naked, feckless Francis (James Bell), the boyfriend of his daughter Charlotte (Shari Sebbens). Ray growls, “How dare you be nude and white in my house.”

Cast of Black is the New White, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Prudence Upton

The restless gravitational centre of Black is the New White is Charlotte’s challenge to her father: that he acknowledge his isolation from his community, that his wealth is disproportionate and that he let through a clause in a Land Rights case that severely disadvantaged his people. This manifests as a furious outburst in the second act but we witness its gradual escalation in the first. Though successful in cases against mining companies in court, Charlotte nonetheless feels out of her depth and is determined to do an advanced degree in New York, to learn how to change the law, not merely exercise it. Ray thinks that Charlotte should take up his activist legacy, doggedly insisting that she not go to New York, but instead accept a TV offer and become “a black female Waleed Aly.”

In Shari Sebbens’ finely nuanced performance we watch the affectionate Charlotte grow increasingly frustrated, attempting to maintain a smile and lay claim to love, honesty and her own place in the world as her father and sister Rose bluntly lay out their opposition to her relationship with Francis. A successful LA-based designer, Rose (Kylie Bracknell [Kaarljilba Kaardn]) is hostile to the diluting of black blood with white — it’s genocide, she claims, citing a 74% Indigenous marriage rate with whites.

Tony Briggs, Melodie Reynolds-Diarra, Black is the New White, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Prudence Upton

Eruptions of confrontation aside, Lui wraps her play like a Christmas present with perpetual joking, amusing political jibes, Francis’ gaffes, communal hilarity (including song and dance), the playful sexuality of the black couples, and the presence of a “Spirit of Christmas” narrator (Luke Carroll) who, novelist-like, fills in back stories while remaining unseen by his subjects. (It’s a limited, thinly integrated role, though played with verve it aptly compounds a sense of the play as fable.)

Black is the New White could conceivably have been built entirely around a black family and a lone white guest, but Lui ramps up the tension and the fun with the eventual arrival of Francis’ parents. Dennison Smith (Geoff Morrell) is a former 1990s right wing conservative parliamentarian and Ray’s political enemy. Lui briskly reveals a man who cannot express love for the son he is determined to push into work by cutting off his allowance, or for his seemingly dotty wife, Marie (Vanessa Downing), whose loneliness and sexual starvation have propelled her into erotic discovery. The revelation is sadly funny in Marie’s telling and Morrell conveys its impact with palpable anguish and physical collapse.

Lui’s sense of humour and the performers’ engagement with it never obscure depth of feeling, although at the end of the play the sheer scale of change, resolution and conciliation, as so often in classic comedy, can only be sketched. Thwarted lovers Charlotte and Francis are reunited by their now bonded fathers (“Yes, a treaty!”). There is forgiveness, faults are admitted, humility attained and, above all, as Joan (whose considerable role in his successful career is admitted by Ray) argues, the preoccupation with difference between black and white must not be obsessed over. (That theme hits home most palpably with regard to the identity of Rose’s husband, Sonny [Anthony Taufa], ex-champion Aboriginal footballer, role model and banker, when he has a DNA test for an appearance on Celebrity Who Do You Think You Are?)

Cast of Black is the New White, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Prudence Upton

Nakkiah Lui’s considerable achievement is to have created a propulsive comedy rich in jokes, pointed ironies and serious commentary that simultaneously spring from the lives of the play’s characters, each of whom is deftly portrayed in word and performance, their souls bared and pain felt. Director Paige Rattray and an admirable cast do great justice to Lui’s play.

The production’s brisk pace allows a stream of politically incorrect utterances (from both sides of the fence) and painfully incisive remarks to fly by, many likely forgotten if cumulatively conjuring a nervy cultural and political context. Perhaps the sheer number of themes lightens the play’s focus, leaving behind a warm ‘she’ll be right’ aura, the kind of coziness often associated with bourgeois comedy. But as Lui has expressly stated, she didn’t want this to be another play about death and depredation, and her play introduces a new world to its white audiences and doubtless Aboriginal ones too. Will Lui, an experimenter to date, be “appropriated” by the comedy of manners after her play’s great success and write more in the same vein, or is she honing her craft and enlarging its range and potential?

It’ll be fascinating to learn what Aboriginal audiences make of Black is the New White if the play gains a wider reach, let alone the likes of Andrew Bolt and the much put-upon David Leyonhjelm — would it be a simple-minded, “Black racism; I told you so”? A favourite line in the play asserts that blacks are not passive-aggressive, it’s a white thing; that got a confirming laugh.

–

Sydney Theatre Company: Black is the New White, writer Nakkiah Lui, director Paige Rattray, performers James Bell, Kylie Bracknell [Kaarljilba Kaardn], Tony Briggs, Luke Carroll, Vanessa Downing, Geoff Morrell, Melodie Reynolds-Diarra, Shari Sebbens, Anthony Taufa, designer Renée Mulder, lighting designer Ben Hughes, composer, sound designer Steve Toulmin; Wharf 1, Sydney, 5 May-17 June

Top image credit: James Bell, Shari Sebbens, Black is the New White, Sydney Theatre Company, photo © Prudence Upton