“We live in a world where there are big films like Alien: Covenant that shine a light into and explain the darkness,” Revelation Perth International Film Festival Program Director Jack Sargeant told RealTime in the lead-up to the festival’s program launch last week. “I grew up with horror films where you didn’t explain the darkness. I find the cultural desire to explain everything really depressing.”

Since its inception in 1997 by founder Richard Sowada, Revelation has maintained a commitment to delineating a space for watching and discussing daring works of independent cinema in counterpoint to the mainstream cinema market. Now, with the festival approaching its 2017 instalment, 6-19 July, both the social and cinema worlds have grown ever-more conservative and difficult to comprehend.

For Sargeant, cinema offers something less than instructive and more interpretive — a place of strange images, sounds and narratives even more fantastical than the real world oddities of President Donald Trump’s tweets, alternative facts and unwinnable wars. “Explaining a truth is overrated in film,” says Sargeant. “I quite like films where nothing is explained. There’s a pleasure in not having a reading of everything.”

Richard Sowada and Jack Sargeant

This approach has produced an eclectic collection of films for the 2017 festival that are “from all kinds of worlds,” and which don’t direct the viewer on how to think. The program encircles what Sargeant calls “weird indie films,” art-house dramas, music and art documentaries, queer films, horror films and children’s films. As well as the continuation of the festival’s academic conference sidebar, there’s “an event called Revel8 that is all about Super 8 film and Super 8 filmmakers; so we have a real love of the living culture of film as a physical medium.”

“All these different kinds of cinema matter,” says Sargeant, despite the fact that most of the films aren’t securing general releases beyond the festival circuit. Notwithstanding their divergences in genre and subject matter, the films Sowada and Sargeant have programmed share the quality of both expressing and contextualising today’s strange feeling of global confusion, and of being part of the “whole world of filmmakers not getting noticed,” despite the popularity and abundance of film festivals.

Women Who Kill

The collision of the horror genre with queer themes is another often-unnoticed realm. Though a highlight of Sydney’s Mardi Gras Film Festival earlier this year, Women Who Kill (2016), will not be securing a general cinema release. Sargeant describes this brilliantly architectured genre film, by debut filmmaker and web-series comedian Ingrid Jungermann, as revelling in “lesbian camp and deadpan” humour. Jungermann’s Morgan is a true-crime podcaster whose rampant commitment-phobia leads her to believe that her new girlfriend, Simone, is not just an eccentric, fallible human but a sociopathic murderer. The film’s central conceit of fear of relationships is transformed into literal horror, the conventions of crime-mystery and slasher films deftly adopted to insert the viewer into Morgan’s paranoid inner world as it grows impossible to know if her fears are real or imagined.

Another curatorial focus is a stream of films in the quasi-documentary mode between fact and fiction. “We live in an era of fake news and virtual existence. I think these hybrid documentary/fiction films expose that,” says Sargeant.” But they also expose our desire for it. It’s that psychological thing of wanting our own confusion to be contextualised. Everything is sort of baffling and strange, and I really want to see films about bafflement. Confusion is a good thing.”

Houston We Have a Problem

The internationally co-produced docufiction, Houston We Have a Problem (Žiga Virc, 2016), runs in this vein. “It’s about the relationship between the USA and Yugoslavia in the space race in the 1960s,” says Sargeant. “It has philosopher Slavoj Žižek in it saying ‘Even if it didn’t happen, it’s true!’ It’s hilarious, with all the touchstones of hybrid documentary cinema today.”

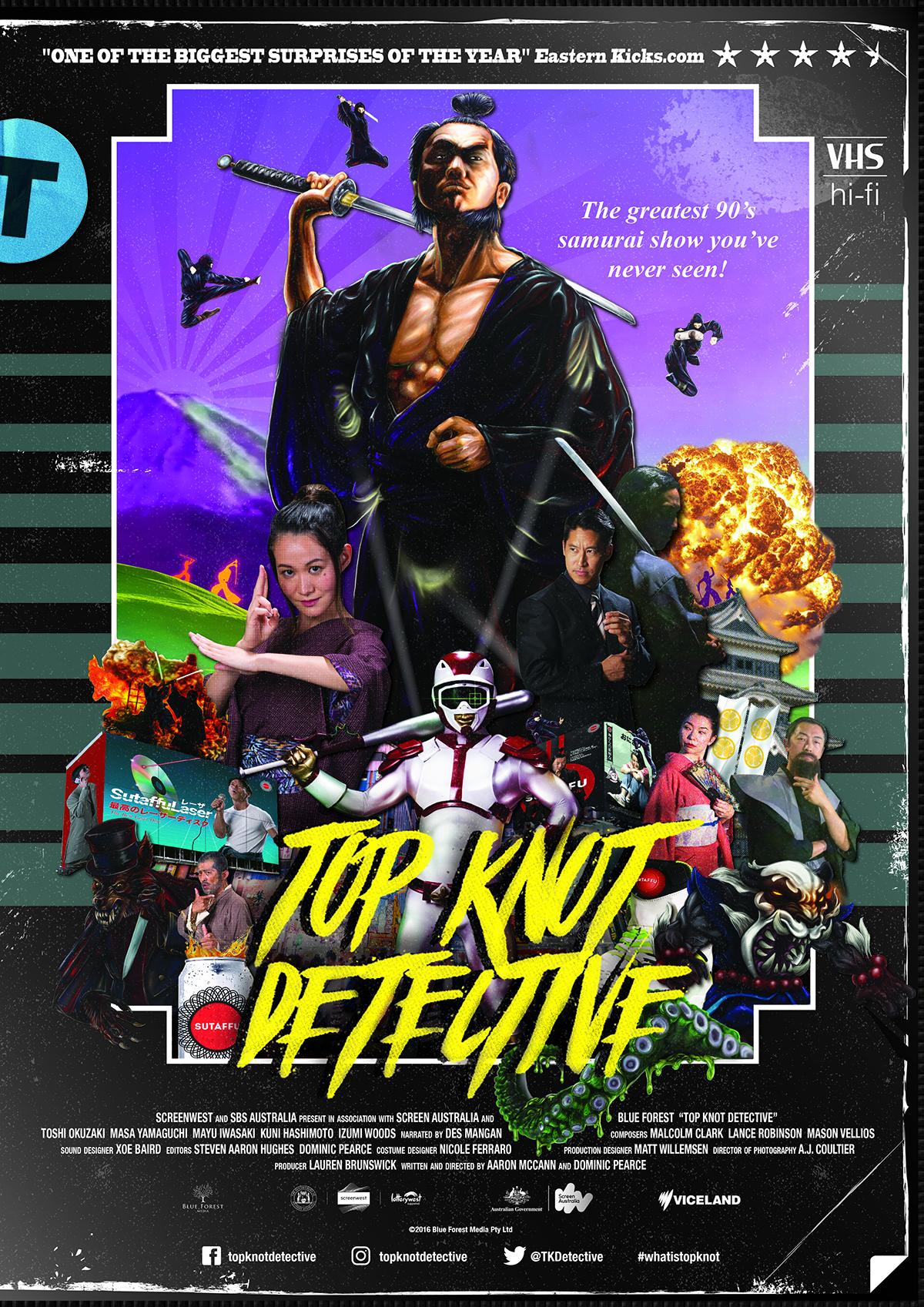

Top Knot Detective

Top Knot Detective

The Western Australian film Top Knot Detective (Aaron McCann and Dominic Pearce, 2016) deploys the mockumentary format to present an homage to “an imaginary cult TV show, and they interview everyone involved in it. You would not know that the TV show is not a thing. It really plays on the audience’s collective experiences and shared cultural memories about half-remembered late night TV. It’s very funny.”

“There is a real sense that both narrative fiction and documentary film aren’t quite enough anymore…[hybrid documentaries] are about how we create, construct, view and examine myth and history. They are just one of the edges of the program, but there are lots of edges.”

A home for the slow-burn film

In its 20th year, Revelation functions at an ironic edge of the film industry, too. The increasingly franchise-soaked film market has led to a growing conservatism and monopolisation of both mainstream and arthouse cinema programming, which has partly led to the space for film festivals to grow and nurture small films squeezed out of general release in cinemas. As such, Sargeant sees Revelation as a unique space in Perth for slow-burn films at the edge of film culture to get a big-screen life.

Cinema: the group experience

Despite the attractions of video-on-demand and home entertainment, “people want to watch films on the big screen,” says Sargeant. “Contrary to popular belief, they don’t just want to watch them on TV. The big screen spectacle is what cinema is all about, the communal experience. My go-to is always Rocky Horror Picture Show. You can’t dance to that by yourself at home. In the cinema it makes sense. When you watch a horror film, you need to be around 200 people. When you’re watching a romance, you want to be crying with everyone. Cinema’s a group experience, and that’s key to our pleasure of cinema.

“There’s a film festival every day of the week. But they all have their own energy and their own identity. Revelation has its own energy. We’re all film nerds, we’re all fans. We have academics and non-academics who are experts in their area. We’re not snobby. I’m not really interested in good film taste. I’m interested in all the different types of culture — music, art — and that feeds into the programming.”

–

Revelation Perth International Film Festival 2017, festival director Richard Sowada, program director Jack Sargeant, Luna Palace, Leederville, Perth, 6-19 July

Top image credit: Women Who Kill

Now in its second year and launching in Sydney this week, the American Essentials film festival brings together an eclectic program of new features, documentaries and classic retrospectives. From Oscar winner Mike Mills’ 1970s-set family drama 20th Century Women, new South Korean-born auteur Kogonada’s intimate romance Columbus and the 1977 Jed Johnson New York comedy Andy Warhol’s Bad, to a new documentary on the visual art of David Lynch, the program traces a rich tradition of restless independent filmmaking. I caught up with American Essentials Artistic Director Richard Sowada to discuss the shifting landscape of festivals and independent cinema, and what the Australian film industry can take away from the work showcased in the program.

LG Like last year’s program, it seems we’re seeing smaller films here that tend to fall through theatrical and festival cracks.

RS They’re becoming rarer to see on any kind of release, these films, because the industry is perhaps losing a bit of trust in the audience, and wanting to take fewer and fewer chances.

LG Is it more economically viable for distributors to bundle these films into a festival, because individually they won’t make money? Is that the mandate?

RS Well, it’s not the mandate but it’s certainly the situation. The mandate behind festivals like this is to bring to light films that would not ordinarily be screened. Often what happens is that film festivals will find themselves going to the traditional marketplaces—Berlin, Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Rotterdam—and then everything else falls in behind that. So the gene pool of films internationally, at film festivals, is largely from the same source.

LG Do you think these types of festivals are making up for a lack of local arthouse and repertory cinema, especially in Sydney?

RS Yes, the film festivals are filling that gap in screens around the country. There’s a film in American Essentials called Columbus, which is great; but because of its more niche nature [“an architectural appreciation symposium grafted onto the skeleton of a fairly typical Sundance drama,” Jordan Hoffman, Vanity Fair, EDs] I guess business backs away and it’s left for the festivals to screen. But what do you call ‘niche’? Is it the kind of person that you think will see the film, or is it the number of people who will come and see it? My general feeling, as a curator observing the industry, is that people in the industry—whether they’re producers, funding agencies, exhibitors, distributors or even punters—will call something niche if they don’t understand it. In my opinion, the more tailor-made you make the suit, the better it looks, and the more people look at it and go, “Oh wow, that looks cool.”

LG Shouldn’t distributors be creating that need for audiences to see the good films?

RS Yeah. It’s kind of a Catch-22 in many ways, in that these films aren’t being selected for commercial release because films like them have been selected before and failed. The next hit is based on the last success—not the current good idea. It’s a constantly backward-looking industry, and I think that the film sector is suffering from that to a degree, and has been for a little while—with the added pressure now of the Netflixes and the Amazons. The industry is going to have to retrain itself to change its perspective.

LG You’ve talked in the past about the nature of these American independent films, and how they’re not defined necessarily by the size of the budget but by their spirit and ideas. There’s a through-line in American independent cinema that we see in the work here, from the micro- to mid-budget to everything in-between. What can Australian filmmakers take away from this? Why aren’t they making work in this tradition, irrespective of the smaller size of the country?

RS That’s a good question. One [lesson] is you’ve just got to take a risk. Don’t compromise on the idea thinking, ‘Oh, if I go too hard here people won’t get it,’ or ‘No one will buy it.’ People like to be looked in the eye and spoken to directly.

LG Do you think funding bodies affect that grasping for broad audience reach? Is that an outmoded thing? How does it change?

RS Yes, yes. It does come from the funding agents, but it’s not just their fault. It comes from the lack of motivation [from filmmakers], to a degree, or a lack of trust in themselves. And the way that it always changes, every single time—I’m saying with a very broad brushstroke—is by doing it, the breakthrough. As soon as there’s something that busts through with its chest out and its legs kicking, people look at it and go, ‘Oh fuck.’ And that becomes the new norm. And you can throw in so many American examples of that, be they Kevin Smith (Clerks) or Tarantino or Kelly Reichardt.

LG Reichardt’s a great example, because her films, especially the earlier ones, are very low budget—but the ideas are there and the filmmaking’s there. You can’t blame a lack of money or infrastructure or whatever; there’s something else going on.

RS No, you can’t. And when you look at them—we screened Reichardt’s first film, River of Grass [1994], last year—they’re fucking incredible. But that is part of a tradition that includes Dennis Wilson’s Two-Lane Blacktop [1971]. It’s a continuum that can be charted through the individuals and through their ideas.

LG Do Australian filmmakers lack that continuum to draw upon and be a part of?

RS Well, yes and no. There is a big gap, no question, in Australian cinema in the 50s and early 60s. But that’s its own wellspring as well; you don’t necessarily need the traditions of cinema; you need to be in tune with what is around you, in your environment, including cinema. But I think that in Australia—very broadly—there is a lack of understanding of the traditions of international cinema. You know: here are the masterworks—let’s look at the Capras, the Maysles and the Pennebakers, and let’s look at the Bergmans and the Wellses.

LG You do sense this a bit with Australian filmmakers. And again, it’s not their fault necessarily, it’s this culture that doesn’t encourage seeking things out. Although America has the benefit of having very rich cultural channels through which to investigate cinema history, I don’t know if that’s the result of training or schooling in cinema.

RS It’s a lot of everything. But ultimately it’s up to the individual. You can talk about the funding agencies and the educational institutions, but it’s up to the individual. If you are into it, then you are into it, and there’s no stopping access, and there’s no stopping reading about the history, and there’s no stopping experiencing or imitating it. All you need is the motivation to dig into the roots. Musicians do it all the time.

LG And we’re in a moment where you have access to more media than ever before.

RS True. I don’t know what it is; it’s kind of like second-guessing the audience, thinking, ‘How can we sell this film,’ rather than ‘What is this film about?’ Again, I think that filmmakers suffer from the same kind of things that distributors may—and I’m not saying that all do—in that the next film is about the next success, not the current good idea. So that’s one of the takeaways. And it’s easy for me to say, but I wasn’t given my life in the arts. I had to really live it. Don’t be afraid. And look at the traditions.

A leading film curator and screen culture advocate, Richard Sowada is the founder and director of the Revelation Perth International Film Festival (1997-present) and was Head of Film Programs at ACMI (2006-15).

Palace Cinemas, American Essentials Film Festival 2017, Artistic Director Richard Sowada, launching Sydney 9 May, Melbourne 11 May, Canberra 16 May, Brisbane 17 May, Adelaide 18 May

Top image credit: Columbus