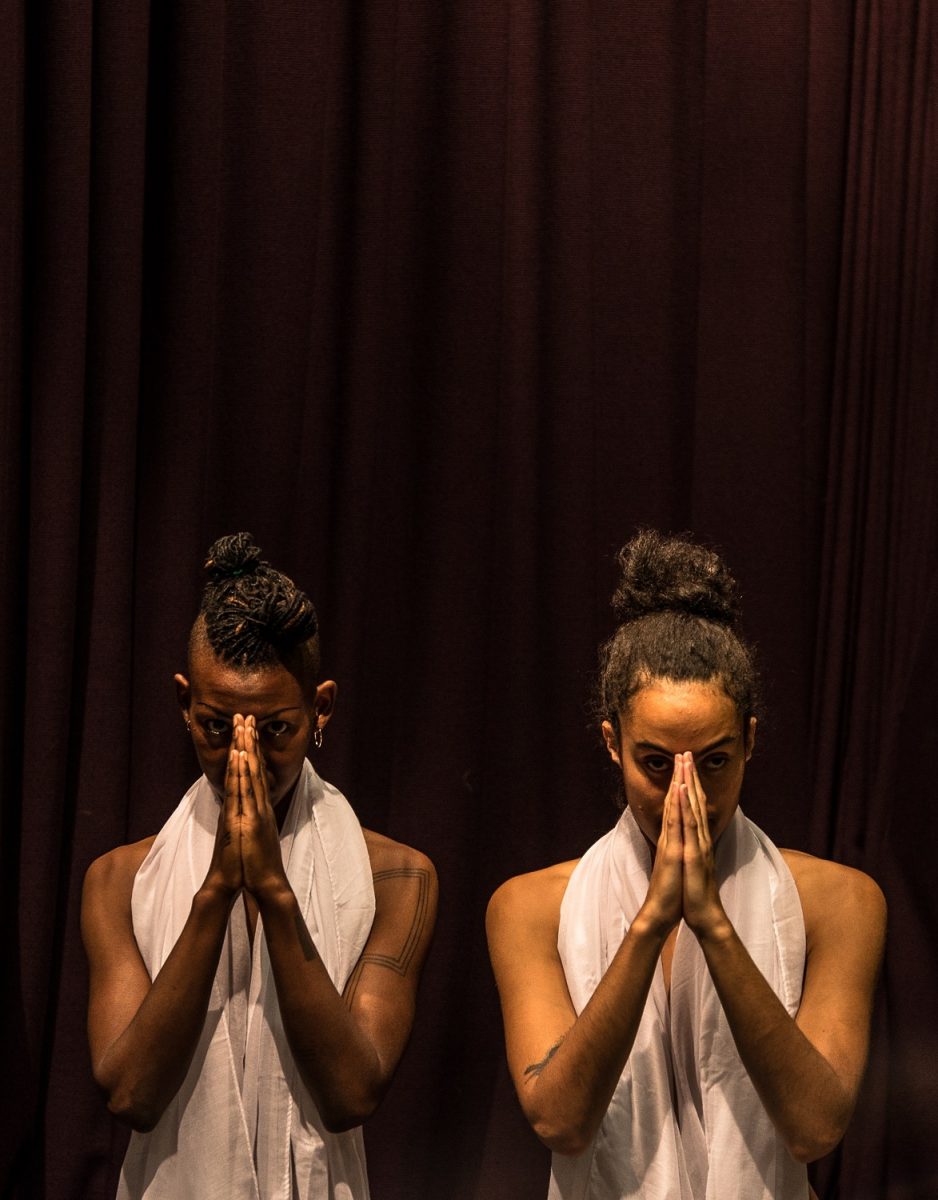

“The two dancers make their way to us in a constrained and systematic series of gestures. They wear white quilted, pleated garments and blocky black high-heeled shoes. They demonstrate a confinement, an entanglement and then a birth. Each emerges with a long steel pin in her hair. White balloons are burst and bones are flung on the floor. They play us, singing, touching, chanting at us.” Osunwunmi, Voodoo, RealTime, 1 March, 2017

In an urgent journey through the haunted territories of diaspora, Project O came to Bristol’s InBetween Time Festival with Voodoo, rigorously demanding from their audience either complicity or confrontation. London-based independent dance artists and collaborators Jamila Johnson-Small and Alexandrina Hemsley talked to me about the work and its roots in the sparkly provocations of O, their previous IBT performance.

JJ I think that O came from quite a fighty place of, like, “Grrrr, we’re here!” And we needed to say these things that weren’t being said. [After] we both went to dance school, I had the idea that I might work for a choreographer. It was horrible, all kinds of fucked up. So for me that was like “Rmph!”

And then people responded [to our work] in lots of ways, but also wanted it. They invited us to spaces, to speak; it seemed like the work was valid to them. And once that happens the fight is different. Now we’re inside, what are we going to say from here?

AH With O, it felt like display. Because, “We’re gonna show you! Because you’re looking at us in the wrong way! We’re going to transform how you look.” Whereas in Voodoo it feels less about showing and more about being or about letting things come: there’s a lot more open improvisation in its current form. Anyway, the work is still in development. It feels like we’ve expanded what we have control over, not just the body but maybe the site that our presence is orientating around. So the world of it feels more considered. It’s quite dystopian: [our] interest in darkening something, darkening the edge of something.

We wanted to hold the same questions that brought us together as a collaboration, about how to live, how to create in this world where various structures almost choreograph you out of them. White supremacist patriarchy is a tough space to exist in, for anybody, but particularly for women and people of colour. So we were holding those questions but wanted to answer them in quite a different way than led our first show.

JJ The thing is the trap of racism and racist structures that I live in and that I just thought were natural. Then you’re like, wait a minute, this doesn’t feel quite right cos I thought this, and then people are treating me like this! And then they’re treating me like that! Then it becomes confusing and you can start to feel you’re going crazy. And you can only know you’re not crazy when someone says, “You’re not crazy” or “I feel that too.” And that’s really important, I think solidarity and other people and discussing things is really important in unpacking this systematic racism. I don’t think you can do that alone.

I’m very concerned with assimilation and ways in which I have internalised assimilationist ideals, intellectually but also physically as I move. And the patterns that my body have gone through in conventional dance training. I’m trying to unpattern and let my body have access to all: trying to let my body be unruly and see what that does. But to try and do that, like how can you let go of everything and still be standing?

Not only the discipline, but to be free of everything. Like, free of the idea that a woman should sit small on a train. Like, I don’t sit small on a train. I sit like this. Now I think more about these things, I wondered when I started sitting like this and why. How that affects how I hold my upper body and what signals I’m trying to send by doing it. And how can I take space in other ways beyond: “I’m just going to take space and I feel really fine like this even though I’m a woman?” How do I just let myself be weird and [find] what makes me feel well? Or what is necessary in this moment and how can I let my body do that? But also still push—not symbolise. This is what I mean: not represent my position but be my position.

I’m interested in the question of how you can stretch anything, how you can expand anything. What else is there in that space beyond what I initially thought. I’m not interested in the conventional aesthetics of virtuosity—but I am interested in it as a concept of expansion or of pushing to the edges of things. And sometimes something falls into something else. Like doing Voodoo as an eight-hour show. I wonder what it would be to encounter that and whether it will be an eight-hour dance show or something else.

AH I think the thing about the traditional aesthetics of virtuosity is that they just exclude so much and so many. Also I feel like any sort of virtuosity is an impossible ideal and I don’t know if I want to spend my life trying to reach impossibility that way. I think the good thing about something being impossible is that it’s endless, it never ends; so if I’m improvising and I’m imagining, then I can just go on and on and on into impossible places.

Watch a video interview with brief performance excerpts here.

Visit Project O’s website.

Top image credit: Project O, O, InBetween Time, 2015, photo Paul Blakemore