With three excellent concerts — a stunning combination of electronic music and dazzling visuals, a biographical portrait of a great painter and a revival of a classic 1960s rock album — this OzAsia Festival covered the widest range of musical and artistic territory.

Regurgitator — The Velvet Underground and Nico

Renowned for reviving great hits, Regurgitator is a rock trio with two regular guests, German-Australian singer and keyboard/synth player Seja, and guzheng player Mindy Meng Wang. 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the seminal 1967 album The Velvet Underground and Nico and this extended Regurgitator line-up has performed this album many times in different contexts, for example at MOFO this year.

In the musical arrangement they have developed, drummer Peter Kostic uses a kit typical of Velvet Underground drummer Moe Tucker’s set-up, emphasising tom-toms and bass drum, frequently using mallets and making little use of cymbals. The significant change to the original arrangement is the introduction of the guzheng, which adds a sonic and cultural dimension to what by 1967 standards was already an experimental sound. The guzheng’s delightful tone lifts the music out of the New York underground and renders it more universal. Presumably the addition of the guzheng provides the Asian link that prompts the inclusion of this production in the OzAsia Festival. In her contributions to this festival, Mindy Meng Wang demonstrated great versatility, and for her work with Regurgitator she creates a unique vocabulary of sound, adding swirls and gestures to the rock arrangement, playing the equivalent of a guitar solo on one track, and contributing an ethereal headiness that gently transforms the music.

The essential strength and character of the original album lies in Lou Reed’s intense and insightful songs such as “I’m waiting for the man,” and many tracks are now considered all-time rock classics, variously musing on drug addiction, sadomasochism, sexual promiscuity and other aspects of 1960s New York life — themes still relevant today. Regurgitator give a fine performance, Seja engagingly delivers Nico’s three songs, and the final track, “European Son,” in the original version of which the musicians really let their hair down, is an invitation to Regurgitator and friends to do likewise. The audience is delighted.

Music in Anticlockwise

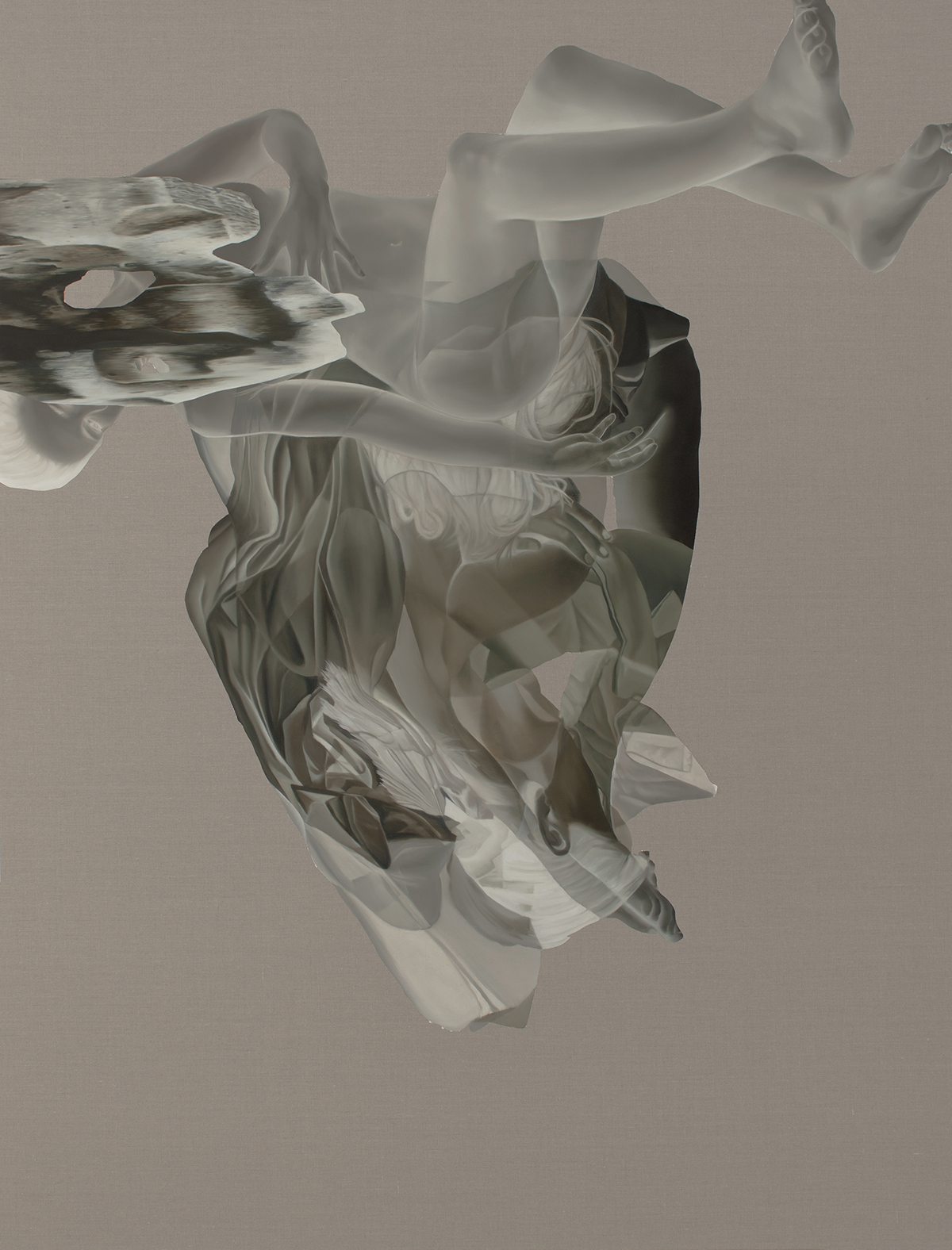

Energetic Hong Kong composer, performer, instrument inventor and visual artist GayBird (Keith Leung Kei-cheuk) produced one of the most optically involving concerts I can recall, as much a visual art experience as a musical one. Working with a team of video, illustration and lighting artists, he uses lasers and a huge LED screen covering the rear of the stage to create a mesmerising cascade of fantasy-inducing visual imagery.

In the first half of the concert, GayBird performs to one side of the stage on synthesisers and voice, creating a web of rhythmic, danceable sound, the music and visuals closely synchronised, creating parallel languages. There are sound samples including one of Stephen Hawking’s computer voice declaring he was born 300 years after Galileo. The screen displays cartoons, abstract imagery and geometric forms, while red laser beams move through the air. This concert bears out GayBird’s statement that, “I don’t divide sound, music, art and technology in my creations, in fact I can’t. I am one person, all my ideas are united as one in my head.”

For the concert’s second half, Zephyr Quartet members were positioned on stage in front of the LED screen while GayBird on the auditorium floor worked at a table of synthesisers, a shallow box with springs stretched over it that he bowed or plucked, and an old manually operated siren. In contrast with the advanced technologies he used in the first half of the concert, some of the devices deployed in the second, never intended as musical instruments, reminded us that interesting sounds may be made from simple means.

GayBird said in a RealTime interview that he chose the concert’s title, Music in Anti-Clockwise, to indicate that he was starting the concert with the future of music and working backwards to early forms, here Haydn’s first string quartet. The version presented here is dramatically reworked and blended with other sounds, perhaps suggesting that our idea of the past is imaginary. The dazzling mix of sound and imagery in this magical concert continued, with added images such as ticking clocks, floating musical notation and keyboards.

GayBird’s performance was preceded by a fine set by Adelaide singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Tracy Chen. Her unobtrusive but sophisticated use of digital technologies to sample and loop her own soft voice and her instruments made for a seductively layered sound. She refers to her creations as ‘bedroom music’ — it can be made at home and has an introspective, melancholic feel, but its complexity and coherence suggest a clear musical vision, perhaps reflecting the direction of future music production. Her gentle sound proved a well-chosen curtain-raiser to Music in Anticlockwise.

Zephyr Quartet, Fairweather, photo Erik Griswold, OzAsia 2017

Fairweather

Legendary Scottish-born painter Ian Fairweather (1891-1974), who spent the latter part of his life in Australia, is revered today as one of our pioneering abstractionists. Dramatically evoking Fairweather’s life, this production combines visual art, music and spoken text, and was developed collaboratively by video artist Glen Henderson, composer Erik Griswold and writer Rodney Hall.

Hall’s narration eloquently captures the central characteristics of Fairweather’s history. The artist spent many years travelling through Asia, particularly China and Indonesia, studied drawing and Japanese language during and after his time as a prisoner in World War I and, later, Chinese visual art and language, also spending some time living in a temple. “China was the nearest place he ever came to home,” says Hall. These experiences deeply affected his thinking and his art. Hall notes that calligraphy, which is central to Fairweather’s art, is “a journey manifested by the hand alone.” In his last years, living on Queensland’s Bribie Island, Fairweather became a scholar-hermit, perhaps in the manner of Chinese antecedents. Such a life story seems surreal: “This is not a life you choose, nor did I,” he had said.

The performance of this 2013 creation is compelling, the images and music subtly underscoring Hall’s text. Griswold’s music is scored for koto, bass koto and string quartet, the opening passages have a Chinese flavour and dramatic passages relating to the war years suggest the psychological disturbance of war. Performers Satsuki Odamura and Adelaide’s much-in-demand Zephyr Quartet are outstanding. At one point, Odamura brushes the bass koto with a small eucalyptus branch, making a soft sound like wind in the island’s trees that is symbolic as much as musical, and she uses the bass koto to suggest swelling ocean waves to accompany the description of Fairweather’s raft journey across the Timor Sea. Griswold’s score for The Raft part 1 (“Epiphany”) is marked ‘hypnotic’ and the music takes us into that dreamy state.

Glen Henderson’s video sets the tone, using layers of imagery in the manner of Fairweather’s paintings. One scene shows an image of the sea through mangroves, the swirling lines of the branches resembling Fairweather’s sinuous drawing. A photographic portrait of the artist can be seen faintly hovering through the branches over the sea like a spirit and it returns regularly to haunt the story.

Following the performance, there is a Q and A session in which Art Gallery of SA curator Tracy Lock introduces the three collaborators and provides important insights into Ian Fairweather’s artwork. Evidently, one painting was found to comprise 70 layers of paint, the layering of imagery becoming a metaphor for the aggregation of life experience. Griswold says that the rhythmic flow of Fairweather’s paintings suggests the flow of music — it inspired his composition and was the genesis of the production. He describes this production as, “a poetic homage to Fairweather… We are trying to create a very immersive experience that will hopefully take you into that psychological mindscape.” Hall, Henderson and Griswold’s Fairweather succeeds wonderfully in this endeavour and is a magnificent portrayal of an artist’s life.

–

OzAsia: Music in Anticlockwise, composer, performer GayBird, Nexus Arts, 6 Oct; Fairweather, Zephyr Quartet, Satsuki Odamura, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, 23 Sept; The Velvet Underground and Nico, Regurgitator, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, 29 Sept

Top image credit: GayBird, photo Cheung Chi Wai, OzAsia 2017

OzAsia Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell’s third festival featured three superb theatrical works — W!ld Rice’s Hotel, Keiichiro Shibuya’s The End and Niwa Gekidan Penino’s The Dark Inn — making my one-week visit supremely worthwhile, with the bonus of the Australian Art Orchestra’s Meeting Points series of wonderful cross-cultural collaborations. Fellow RealTime writers Chris Reid and Ben Brooker have made clear their praise for much else in the three-week festival that opens us up to works made here and in Asia that expand our sense of what is possible artistically and what we can learn culturally.

Two men, a son and his dwarf father, arrive at a remote hot springs country inn, named Avidya (ignorance), located, a narrator tell us, in Hell Valley. The pair have been invited to entertain the inn’s guests with their puppetry, but it turns out they’re not expected and that the owner is not present. An old woman is unhelpful, though father and son seem unfazed, even when they discover they’ve missed the last bus. The woman relents and offers them a room. Action to this point, and for much of The Dark Inn, moves at a leisurely, often less than everyday pace. The acting is low-key, voices quietly projected. We are compelled to look in on an unfamiliar world with few signs of the present, despite our being told it’s 2013.

The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino, OzAsia 2017

The intricately realistic timber-framed set revolves with cinematic verve from reception to bedrooms on two levels, to a changing room and then a rock-girded, steaming hot spring bath. Seen though a rear window is a persimmon tree, its leaf fall and flowering indicating the seasonal change pivotal to the play’s meanings, first unhurriedly revealed as the characters observe the social niceties; when they don’t, physical and emotional chaos ensue. While first expectations are that the father, Momofuku Kurata, and son, Ichiro, will fall prey to whatever absurdist situation they’ve found themselves in, in fact they will be catalysts for change, some of it already brewing.

The two-and-a-half hour play is not easily summarised, so I’ll follow one thread. A sense of growing unease is triggered in small increments. Kurata and Ichiro find a guest in their room, the blind Matsuo, who believes the hot spring will cure him. His earnest soul-seeking is deflated by the pair, Kurata bluntly hinting that masturbation might help and, before they are interrupted, asking if would he like to be touched. Matsuo wishes he could see the father and son; Kurata says, “I’m horrible, my son’s even more so.”

When father and son are cajoled into performing by two drunken geisha (resting at the inn in the off-season) who have entertained them with a “snappy” shamisen duet, the bright yellow puppet — a little larger than Kurata and with a big head and outsize hands — is slowly revealed. Kurata activates it, lunging about, mounting and being mounted by the creature and gasping with post-coital relief. Everyone’s shocked — the geishas, the bathroom assistant peering through the window, and Matsuo, who doesn’t like what he hears and flees the room. However, his curiosity persists; he seeks out the puppet and, horrified by what he finds, screams and curls up naked in the bathroom. But Matsuo’s already been dealt a blow by Ichiro when he tries to draw the young man into a discussion, in Buddhist terms, about escaping ignorance. Ichiro cuts him off; abstractions will not cure Matsuo. In the play’s climactic scene, Kuratu and Ichiro, about to leave the inn, invade the bathroom, where the guests are recovering from their diverse crises, with the puppet, revealing its huge penis. Matsuo vomits.

Takiko, the old woman, will call Ichiro “lightless” (effectively” ignorant”) for his treatment of the blind man, but come spring, Matsuo has left the inn on which he had become helplessly dependent. Ichiro reveals his own plight — “a life without choices,” he’s unschooled and unable to abandon his father, whom he treats with utmost deference. A rare smile passes between them as they leave the inn — perhaps a kind of ‘mission accomplished’ by two tricksters.

The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino, OzAsia 2017

Each of the inn’s residents has problems to resolve. The elder geisha plays mother to the younger but knows she must let her go, into the arms of a traditional bath attendant, a Nagashi (one of a dying breed), a giant, bumbling sexually repressed mute who has to comically fan his erection when Kurata undresses to bathe and lets down his long black locks. Takiko wanted to become a geisha in the 40s, learned the shamisen but WWII eventuated, she wasn’t pretty anyway and grew old and envious. We know least about the elegant, self-contained Kurata (Mame Yamada), but his liberating provocations are central to The Dark Inn. Ignorance of the body — a form of self-deception — and its needs are as fateful as ignorance of mind. Though not a Buddhist, writer-director Kurô Tanino said in an interview, “the characters are based on 12 Buddhist ideas, such as Avidya, ‘no light,’ which can mean no knowledge or being lost.”

The Dark Inn’s larger picture entails not only the ritual renewal of Spring — the younger geisha and the bath attendant have a baby and the other residents have returned to the world. However, there are no new guests and a new railway line threatens demolition; geishas, bath attendants and travelling puppeteers perhaps barely belong in the play’s 2013. The Dark Inn is neither defeatist nor wilfully optimistic; it is playfully pragmatic.

The production’s pacing is deeply engaging, its incremental surprises and escalating shocks bracing and rich in meaning. The performances are subtly informal and beautifully shaped across the play’s uninterrupted two-and-a-half hours. Set, lighting and sound design are superbly integrated. Director (and psychiatrist) Kurô Tanino’s cogent assemblage of the complex components of The Dark Inn yields a deeply memorable experience in which time is tellingly distended, opening up our attention and incisively putting ignorance to the test.

–

OzAsia: Niwa Gekidan Penino, The Dark Inn, writer, director Kurô Tanino, design Kurô Tanino, Michiko Inada, lighting Masayuke Abe, Kosuke Ashidano, sound design Koji Sato, Yoshihiro Nakamura, technical director Isao Hubo; Her Majesty’s Theatre, Adelaide, 3-4 Oct

Top image credit: The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino, OzAsia 2017

In our concern with the negative effects of colonialism, we often overlook the enrichment that cross-cultural intercourse can bring. Macau Days offers a glimpse of that enrichment by illuminating the history and mythology of Macau, a 500-year-old European outpost and the first European settlement in Asia. A collaborative work by visual artist John Young, author Brian Castro and composer Luke Harrald, Macau Days includes a book of the same title by Castro (himself of Portuguese, Chinese and English parentage) and Young (Chinese and French-Dutch). All are Australian residents, and both Castro and Young were born in Hong Kong which neighbours Macau. The exhibition demonstrates the human need for travel and migration in personal and spiritual growth.

The beautifully produced and illustrated trilingual book is itself an art object, comprising poems by Castro and Paul Carter inspired by Macau’s colonial history, an introductory essay by Art + Australia editor Ted Colless, and images of Young’s artwork. Castro’s delightful and darkly humorous poems, collectively entitled Macau Days: or Six Poems in Search of a Dish, bring to life six characters he has discovered who exemplify Macau’s history — the Chinese sea goddess Mazu (originating c 960, and whose name may have been the source of the name “Macau”), the Portuguese poet Luis Vaz de Camões (born c 1524), Chinese poet and painter Wu Li (born 1632, an early convert to Christianity following the arrival of the Jesuits), court artist and Jesuit Giuseppe de Castiglione (born 1688), Portuguese writer and Japanophile Wenceslau de Moraes (born 1854) and Portuguese poet Camillo Pessanha (born 1867).

Castro includes recipes that reflect Macau’s multicultural nature and invites readers to prepare their own dishes to recreate the character of Macau on the premise that food is emblematic of culture and identity. He researched his subjects closely and these recipes were evidently the favourites of the six characters — it’s as if we could enter their hearts and minds or become Macanese by eating these tantalising concoctions.

Mazu, Goddess of the Sea, John Young, Macau Days, image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

The visual component of the exhibition, John Young’s outstanding Macau Days series (2012), comprises several paintings in which images resembling photographic negatives or digital prints of old photos are overlaid with coloured abstract imagery. The figure of a woman in these paintings evocatively represents the goddess Mazu. A series of digitally reproduced historical photographs evoke the history of Macau with, for example, images of significant buildings such as Jesuit churches and a photo of Wenceslau de Moraes in Japanese garb with a small child. And there are texts chalked on paper painted with blackboard paint, as if lessons were being learnt (perhaps in a Jesuit school). These texts are personal musings, for example “to the ends of the world to find my anima,” “our souls meet here” and “absolutely foreign — see how I became.” Some of these chalk-on-paper works bear erasures and re-inscriptions, as if thoughts have been corrected. Young’s layering, corrections and juxtapositions symbolise the layering and juxtaposition of cultures found not only in Macau but throughout the world.

Luke Harrald’s meditative sound installation is a 21-minute tape loop of voices reading Castro’s poems in Mandarin, Portuguese and English. Depending on where you stand in the gallery, you hear each reader separately and quite distinctly. In the background are field recordings of splashing water, bells, street noises, voices and horses’ hooves evoking old Macau’s aural character. The whole exhibition is an immersive and enchanting experience, part history and part magic realism, and it could only be improved by adding servings from Castro’s menu.

The crucial point of the exhibition is that our subjectivity determines our response to colonisation, migration and cultural hybridisation. Of Young’s artworks, Castro writes: “Having studied Ludwig Wittgenstein/ you know that culture determines/ the way we see; that a person’s name/ is, has to be, the picture of a situation./ Doubled and tripled we crossed borders/ easily; but now the paranoia of ignorance/ has folded up your tapestry/ and it’s a DNA test for ancestry/ which supposedly clarifies how/ humanity runs in generations/ alongside insanity/ depending on the periodic flood/ that brings on the clash of blood.”

The colourful history of Macau shows how travel and migration are long-standing human traditions, precipitating enrichment and development. As Ted Colless puts it in his introductory essay: “In this spectral and sensual liquidity of Macau — a version of the city not so much groundless but ungrounded: a city (as one tourist brochure puts it) with no flora and fauna to speak of — borders become porous or ebb and flow, and the earnest chauvinism of identity politics can be supplanted by mashups and medleys.”

–

OzAsia Festival: Macau Days, artists John Young, Brian Castro, Luke Harrald; Migration Museum, Adelaide, 23 Sept– 8 Oct

Top image credit: Marienbad, John Young, Macau Days, image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

Singapore has just celebrated the 52nd year of its independence as a nation, it’s a multicultural society of immigrants and their descendants and its music draws on many traditions, particularly Chinese. The three members of SA the Collective grew up experiencing a mélange of musical traditions, not only from within Singapore but across the globe. They especially look to their Chinese ancestry in developing their music, which embraces experimental as well as classical Chinese styles.

Formed in 2011, SA the Collective comprises Andy Chia on dizi (Chinese flute), dijeridu, vocals and electronics, Natalie Alexandra on guzheng (Chinese zither) and electronics and Cheryl Ong on drums, percussion and electronics. All were trained from an early age on their Chinese instruments. The band’s name includes SA, which in Chinese means three, is from a northern dialect and was chosen to evoke the artists’ origins.

The ensemble travels widely, performing in locations as diverse as Museum Siam in Bangkok and the International Society for Music Education’s 32nd World Conference (Glasgow, 2016). They blend dijeridu and overtone singing with modified versions of traditional Chinese and other instruments, all of which they mediate electronically to create a unique and compelling sonic tapestry. A blend of genres, their music hints at rock, jazz and ambient drone, and can involve multiple rhythms and a blend of chromatic and pentatonic scales, often in long, swirling improvisations. Their use of looping to add layers of sound and extended instrumental techniques, such as bowing or tapping the guzheng instead of plucking, and channelling it through effects pedals, broadens and enriches their sonic palette. Their music can be quietly meditative, hauntingly beautiful, joyously danceable or overwhelmingly powerful and complex.

SA (仨 ) photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

The instrumentation is significant for the trio, not just for its sonic potential but for the mixing of musical traditions. Andy Chia said that while they are aware of the cultural significance of particular instruments and musical forms, “For us [in Singapore] everything is borrowed, the language we speak is borrowed… Our ancestry might be from China but we are not really connected with and are constantly borrowing from it.”

Cultural identity seems a perennial issue in Singapore. Cheryl Ong feels that Singaporeans are more Southeast Asian: “although we are by race Chinese, because our ancestry came from China, we don’t really carry that baggage of tradition anymore.” Their intention, as outlined on their Soundcloud page is “to create Musical Art that represents their modern identity as Chinese from a diaspora.” Their latest release, titled Flow, demonstrates how the trio weaves new music out of traditional forms and aesthetics, reinventing traditional Chinese music and bringing it into a high-tech, globalised world.

In planning their program for OzAsia in Adelaide, Cheryl says the trio will play some of their current repertoire and perform some improvisations. Andy suggests, “a lot of it has to do with the people that are there, the environment and of course ourselves, and in that sense these three elements will mix to create the sonic experience you will hear.” Their forthcoming OzAsia perfomances will be their only Australian appearances.

See SA the Collective performing and explaining how they play.

–

OzAsia Festival: SA the Collective, Moon Lantern Festival, Elder Park, 1 Oct, 5pm; Lucky Dumpling Market, Convention Centre Lawn, Adelaide, 2 Oct, 7pm

Chris Reid spoke to SA the Collective in Singapore courtesy of Culturelink and the Adelaide Festival Centre.

Top image credit: SA (仨 ) photo courtesy OzAsia 2017