Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

With three excellent concerts — a stunning combination of electronic music and dazzling visuals, a biographical portrait of a great painter and a revival of a classic 1960s rock album — this OzAsia Festival covered the widest range of musical and artistic territory.

Regurgitator — The Velvet Underground and Nico

Renowned for reviving great hits, Regurgitator is a rock trio with two regular guests, German-Australian singer and keyboard/synth player Seja, and guzheng player Mindy Meng Wang. 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of the seminal 1967 album The Velvet Underground and Nico and this extended Regurgitator line-up has performed this album many times in different contexts, for example at MOFO this year.

In the musical arrangement they have developed, drummer Peter Kostic uses a kit typical of Velvet Underground drummer Moe Tucker’s set-up, emphasising tom-toms and bass drum, frequently using mallets and making little use of cymbals. The significant change to the original arrangement is the introduction of the guzheng, which adds a sonic and cultural dimension to what by 1967 standards was already an experimental sound. The guzheng’s delightful tone lifts the music out of the New York underground and renders it more universal. Presumably the addition of the guzheng provides the Asian link that prompts the inclusion of this production in the OzAsia Festival. In her contributions to this festival, Mindy Meng Wang demonstrated great versatility, and for her work with Regurgitator she creates a unique vocabulary of sound, adding swirls and gestures to the rock arrangement, playing the equivalent of a guitar solo on one track, and contributing an ethereal headiness that gently transforms the music.

The essential strength and character of the original album lies in Lou Reed’s intense and insightful songs such as “I’m waiting for the man,” and many tracks are now considered all-time rock classics, variously musing on drug addiction, sadomasochism, sexual promiscuity and other aspects of 1960s New York life — themes still relevant today. Regurgitator give a fine performance, Seja engagingly delivers Nico’s three songs, and the final track, “European Son,” in the original version of which the musicians really let their hair down, is an invitation to Regurgitator and friends to do likewise. The audience is delighted.

Music in Anticlockwise

Energetic Hong Kong composer, performer, instrument inventor and visual artist GayBird (Keith Leung Kei-cheuk) produced one of the most optically involving concerts I can recall, as much a visual art experience as a musical one. Working with a team of video, illustration and lighting artists, he uses lasers and a huge LED screen covering the rear of the stage to create a mesmerising cascade of fantasy-inducing visual imagery.

In the first half of the concert, GayBird performs to one side of the stage on synthesisers and voice, creating a web of rhythmic, danceable sound, the music and visuals closely synchronised, creating parallel languages. There are sound samples including one of Stephen Hawking’s computer voice declaring he was born 300 years after Galileo. The screen displays cartoons, abstract imagery and geometric forms, while red laser beams move through the air. This concert bears out GayBird’s statement that, “I don’t divide sound, music, art and technology in my creations, in fact I can’t. I am one person, all my ideas are united as one in my head.”

For the concert’s second half, Zephyr Quartet members were positioned on stage in front of the LED screen while GayBird on the auditorium floor worked at a table of synthesisers, a shallow box with springs stretched over it that he bowed or plucked, and an old manually operated siren. In contrast with the advanced technologies he used in the first half of the concert, some of the devices deployed in the second, never intended as musical instruments, reminded us that interesting sounds may be made from simple means.

GayBird said in a RealTime interview that he chose the concert’s title, Music in Anti-Clockwise, to indicate that he was starting the concert with the future of music and working backwards to early forms, here Haydn’s first string quartet. The version presented here is dramatically reworked and blended with other sounds, perhaps suggesting that our idea of the past is imaginary. The dazzling mix of sound and imagery in this magical concert continued, with added images such as ticking clocks, floating musical notation and keyboards.

GayBird’s performance was preceded by a fine set by Adelaide singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Tracy Chen. Her unobtrusive but sophisticated use of digital technologies to sample and loop her own soft voice and her instruments made for a seductively layered sound. She refers to her creations as ‘bedroom music’ — it can be made at home and has an introspective, melancholic feel, but its complexity and coherence suggest a clear musical vision, perhaps reflecting the direction of future music production. Her gentle sound proved a well-chosen curtain-raiser to Music in Anticlockwise.

Zephyr Quartet, Fairweather, photo Erik Griswold, OzAsia 2017

Fairweather

Legendary Scottish-born painter Ian Fairweather (1891-1974), who spent the latter part of his life in Australia, is revered today as one of our pioneering abstractionists. Dramatically evoking Fairweather’s life, this production combines visual art, music and spoken text, and was developed collaboratively by video artist Glen Henderson, composer Erik Griswold and writer Rodney Hall.

Hall’s narration eloquently captures the central characteristics of Fairweather’s history. The artist spent many years travelling through Asia, particularly China and Indonesia, studied drawing and Japanese language during and after his time as a prisoner in World War I and, later, Chinese visual art and language, also spending some time living in a temple. “China was the nearest place he ever came to home,” says Hall. These experiences deeply affected his thinking and his art. Hall notes that calligraphy, which is central to Fairweather’s art, is “a journey manifested by the hand alone.” In his last years, living on Queensland’s Bribie Island, Fairweather became a scholar-hermit, perhaps in the manner of Chinese antecedents. Such a life story seems surreal: “This is not a life you choose, nor did I,” he had said.

The performance of this 2013 creation is compelling, the images and music subtly underscoring Hall’s text. Griswold’s music is scored for koto, bass koto and string quartet, the opening passages have a Chinese flavour and dramatic passages relating to the war years suggest the psychological disturbance of war. Performers Satsuki Odamura and Adelaide’s much-in-demand Zephyr Quartet are outstanding. At one point, Odamura brushes the bass koto with a small eucalyptus branch, making a soft sound like wind in the island’s trees that is symbolic as much as musical, and she uses the bass koto to suggest swelling ocean waves to accompany the description of Fairweather’s raft journey across the Timor Sea. Griswold’s score for The Raft part 1 (“Epiphany”) is marked ‘hypnotic’ and the music takes us into that dreamy state.

Glen Henderson’s video sets the tone, using layers of imagery in the manner of Fairweather’s paintings. One scene shows an image of the sea through mangroves, the swirling lines of the branches resembling Fairweather’s sinuous drawing. A photographic portrait of the artist can be seen faintly hovering through the branches over the sea like a spirit and it returns regularly to haunt the story.

Following the performance, there is a Q and A session in which Art Gallery of SA curator Tracy Lock introduces the three collaborators and provides important insights into Ian Fairweather’s artwork. Evidently, one painting was found to comprise 70 layers of paint, the layering of imagery becoming a metaphor for the aggregation of life experience. Griswold says that the rhythmic flow of Fairweather’s paintings suggests the flow of music — it inspired his composition and was the genesis of the production. He describes this production as, “a poetic homage to Fairweather… We are trying to create a very immersive experience that will hopefully take you into that psychological mindscape.” Hall, Henderson and Griswold’s Fairweather succeeds wonderfully in this endeavour and is a magnificent portrayal of an artist’s life.

–

OzAsia: Music in Anticlockwise, composer, performer GayBird, Nexus Arts, 6 Oct; Fairweather, Zephyr Quartet, Satsuki Odamura, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, 23 Sept; The Velvet Underground and Nico, Regurgitator, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, 29 Sept

Top image credit: GayBird, photo Cheung Chi Wai, OzAsia 2017

OzAsia Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell’s third festival featured three superb theatrical works — W!ld Rice’s Hotel, Keiichiro Shibuya’s The End and Niwa Gekidan Penino’s The Dark Inn — making my one-week visit supremely worthwhile, with the bonus of the Australian Art Orchestra’s Meeting Points series of wonderful cross-cultural collaborations. Fellow RealTime writers Chris Reid and Ben Brooker have made clear their praise for much else in the three-week festival that opens us up to works made here and in Asia that expand our sense of what is possible artistically and what we can learn culturally.

Two men, a son and his dwarf father, arrive at a remote hot springs country inn, named Avidya (ignorance), located, a narrator tell us, in Hell Valley. The pair have been invited to entertain the inn’s guests with their puppetry, but it turns out they’re not expected and that the owner is not present. An old woman is unhelpful, though father and son seem unfazed, even when they discover they’ve missed the last bus. The woman relents and offers them a room. Action to this point, and for much of The Dark Inn, moves at a leisurely, often less than everyday pace. The acting is low-key, voices quietly projected. We are compelled to look in on an unfamiliar world with few signs of the present, despite our being told it’s 2013.

The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino, OzAsia 2017

The intricately realistic timber-framed set revolves with cinematic verve from reception to bedrooms on two levels, to a changing room and then a rock-girded, steaming hot spring bath. Seen though a rear window is a persimmon tree, its leaf fall and flowering indicating the seasonal change pivotal to the play’s meanings, first unhurriedly revealed as the characters observe the social niceties; when they don’t, physical and emotional chaos ensue. While first expectations are that the father, Momofuku Kurata, and son, Ichiro, will fall prey to whatever absurdist situation they’ve found themselves in, in fact they will be catalysts for change, some of it already brewing.

The two-and-a-half hour play is not easily summarised, so I’ll follow one thread. A sense of growing unease is triggered in small increments. Kurata and Ichiro find a guest in their room, the blind Matsuo, who believes the hot spring will cure him. His earnest soul-seeking is deflated by the pair, Kurata bluntly hinting that masturbation might help and, before they are interrupted, asking if would he like to be touched. Matsuo wishes he could see the father and son; Kurata says, “I’m horrible, my son’s even more so.”

When father and son are cajoled into performing by two drunken geisha (resting at the inn in the off-season) who have entertained them with a “snappy” shamisen duet, the bright yellow puppet — a little larger than Kurata and with a big head and outsize hands — is slowly revealed. Kurata activates it, lunging about, mounting and being mounted by the creature and gasping with post-coital relief. Everyone’s shocked — the geishas, the bathroom assistant peering through the window, and Matsuo, who doesn’t like what he hears and flees the room. However, his curiosity persists; he seeks out the puppet and, horrified by what he finds, screams and curls up naked in the bathroom. But Matsuo’s already been dealt a blow by Ichiro when he tries to draw the young man into a discussion, in Buddhist terms, about escaping ignorance. Ichiro cuts him off; abstractions will not cure Matsuo. In the play’s climactic scene, Kuratu and Ichiro, about to leave the inn, invade the bathroom, where the guests are recovering from their diverse crises, with the puppet, revealing its huge penis. Matsuo vomits.

Takiko, the old woman, will call Ichiro “lightless” (effectively” ignorant”) for his treatment of the blind man, but come spring, Matsuo has left the inn on which he had become helplessly dependent. Ichiro reveals his own plight — “a life without choices,” he’s unschooled and unable to abandon his father, whom he treats with utmost deference. A rare smile passes between them as they leave the inn — perhaps a kind of ‘mission accomplished’ by two tricksters.

The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino, OzAsia 2017

Each of the inn’s residents has problems to resolve. The elder geisha plays mother to the younger but knows she must let her go, into the arms of a traditional bath attendant, a Nagashi (one of a dying breed), a giant, bumbling sexually repressed mute who has to comically fan his erection when Kurata undresses to bathe and lets down his long black locks. Takiko wanted to become a geisha in the 40s, learned the shamisen but WWII eventuated, she wasn’t pretty anyway and grew old and envious. We know least about the elegant, self-contained Kurata (Mame Yamada), but his liberating provocations are central to The Dark Inn. Ignorance of the body — a form of self-deception — and its needs are as fateful as ignorance of mind. Though not a Buddhist, writer-director Kurô Tanino said in an interview, “the characters are based on 12 Buddhist ideas, such as Avidya, ‘no light,’ which can mean no knowledge or being lost.”

The Dark Inn’s larger picture entails not only the ritual renewal of Spring — the younger geisha and the bath attendant have a baby and the other residents have returned to the world. However, there are no new guests and a new railway line threatens demolition; geishas, bath attendants and travelling puppeteers perhaps barely belong in the play’s 2013. The Dark Inn is neither defeatist nor wilfully optimistic; it is playfully pragmatic.

The production’s pacing is deeply engaging, its incremental surprises and escalating shocks bracing and rich in meaning. The performances are subtly informal and beautifully shaped across the play’s uninterrupted two-and-a-half hours. Set, lighting and sound design are superbly integrated. Director (and psychiatrist) Kurô Tanino’s cogent assemblage of the complex components of The Dark Inn yields a deeply memorable experience in which time is tellingly distended, opening up our attention and incisively putting ignorance to the test.

–

OzAsia: Niwa Gekidan Penino, The Dark Inn, writer, director Kurô Tanino, design Kurô Tanino, Michiko Inada, lighting Masayuke Abe, Kosuke Ashidano, sound design Koji Sato, Yoshihiro Nakamura, technical director Isao Hubo; Her Majesty’s Theatre, Adelaide, 3-4 Oct

Top image credit: The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino, OzAsia 2017

We return from Adelaide, bearing delights and insights granted us by the artists whose work we experienced in just one of the three weeks of OzAsia Festival. Singapore’s Hotel, reviewed this week, and Japan’s The Dark Inn, expanded and deepened our sense of time as well as sharpening our cultural awareness. Also from Japan, Keiichiro Shibuya’s opera The End for virtual pop star Miku transcended its pop sources with tragic heft. Reviews of this and The Dark Inn next week. Ben Brooker welcomes OzAsia performances by Akram Khan, Eisa Jocson and Checkpoint Theatre that spoke powerfully to the complexities of gender, and Chris Reid embraces the festival’s visual arts program. Now it’s Sydney’s turn to enjoy the growing Australian-Asian symbiosis in Performance Space’s Liveworks which features works from Japan, South Korea and the Philippines alongside Australian creations, including Justin Shoulder’s Carrion [image above]. Art that unites in a time of division! Keith & Virginia

–

Top image credit: Justin Shoulder, Carrion, 2017, photo courtesy Performance Space

At the opening of W!ld Rice Theatre’s Hotel and from time to time between episodes, performers in black fill the stage as if citizens (singing “Rule Brittania” or Singapore’s national anthem), travellers (the nation state’s influx of diaspora) or hotel staff — unpacking their livery or practising routine tasks. Two walls and assortments of furniture draw in to complete a room with two entrances. Changing rear-projected wall-paper and costuming deftly signify eras, as do documentary photographs, film footage and other images, such as for The Good Manners Campaign accompanied by the singing of “Stand up for Singapore.” It’s a space cleverly designed for a close encounter with a culture unfamiliar to most Australians, but in many ways close to home.

Hotel comprises 11 plays, each around half an hour, each with a bracing sting in the tail, all linked by being set in one hotel room à la Raffles and unfolding over the course of 100 years in one nation state, Singapore, from British colonial rule to independence from Malaysia in 1965 and on to the present, and performed in two gripping two-and-a-half hour instalments.

An ensemble of 14 role-changing, sometimes gender-swapping performers virtuosically engage in situation comedy, wild farce, high drama and song and dance. What unites all of these apparently disparate components is an unremitting focus on Singaporean culture in terms of race, class, religion and gender, evoking at once rich diversity and unresolved tensions. What makes Hotel deeply fascinating is its dramatically rich account of the escalating complexity of Singapore’s racial and cultural diversity, unforgettably felt not least in the production’s last scene. But I’ll begin at the very beginning of Hotel and then jump to the end.

Hotel, W!LD RICE, photo courtesy the artists and OzAsia 2017

From first to last: the drama of diversity

In the first scene, in 1915, the Eurasian and devoutly Christian wife of a racist, sexist and bullying English planter is shocked when he delightedly insists they attend the public execution of some 50 Sepoys: Muslim Indian soldiers in the British army who had violently mutinied in protest at being sent to fight against Muslim Turkey. She defiantly refuses to attend, her husband departs, she communicates sympathetically in Malay with a Muslim bellboy who admits a desire to “kill every white face,” gives him a valuable necklace (a gift from her husband a short while before) and, deciding to leave her husband, exits for the Sepoy lines. Her act won’t upset the status quo but it indicates the depth of the tensions that will drive Hotel. Shots are heard, the cast sing “Land of hope and glory” at the end of a scene that commenced with “Rule Britannia.”

The scene plays out tensely, the wife reserved, consistently insulted for being a woman and of mixed race and then nervously frantic under pressure. But in her husband’s absence, a sense of resolve firms. It’s a surprisingly rapid but convincing release, in a scene already focused on power, class, gender and the ‘otherness’ of being Eurasian and, under British rule, Malay. That ‘otherness’ will play out across the hours in many permutations as will the role of language in throwing up barriers or allowing alternative expression.

While this might seem like a thematically complex beginning, compared with what’s to come it’s relatively simple if true to the way most scenes play out: a social binary will be met with a third element, either from within the pair, or from without, in a recurring dialectical dynamic.

In Hotel’s final scene, set in the present — if with an air of prophesy — an elderly man (Ivan Heng, one of Hotel’s two directors) and his wife have installed themselves in the hotel room, with a nurse, as long-term residents. Because he’s ill, management are not keen on having the hotel treated like a hospital. The scene is built around the seemingly well-to-do Singaporean Chinese couple’s resistance to being moved out. As pressure builds, what commenced as comedy — including the wife’s blunt sexual comments and her husband’s curmudgeonly casual racism towards his daughter’s Mauritian husband (who fights back) — turns ever so gradually dark. Under pressure from management, he reveals he’s dying of prostate cancer and asks to see the hotel staff whom he thanks and quizzes about their origins, revealing diversity beyond the anticipated Chinese, Malay and Indian mix and including two mainland Chinese workers who, to his surprise, speak no English. “What’s the need?”, is the response, an indication that Singapore is changing beyond the comprehension of a member of a cultural group that comprises 76% of the state’s population and whose first language is English.

Even the man’s economic standing has been undermined: he reveals that his and his wife’s properties have been sold out from under them by developers, that the couple have tried unsuccessfully to live with their adult children in Australia and returned home to enable him to die in peace and comfort in a hotel room. This revelation tempers our dislike for the man and we’re amused by his allowing the staff to take selfies with him and shake his hand, but it’s his words to them about “home” that cut deep and shift the play’s mood into sadness. Asked why he decided to spend his last days in a hotel room, he says, underlining the many different periods and states of being in Hotel, that the room is “a temporary space” and that “home” is “all an illusion.” He feels, in effect, that his kind are on their way, sooner or later, to becoming the ‘others’ he has mocked. This final scene — typically compact, linguistically sharp and deft at briskly changing the emotional temperature — tautly draws together the thematic threads of Hotel’s rich weave. It acknowledges a persistent preoccupation, as one character in this scene puts it: “We don’t even know what to do with diversity,” while revealing an already arriving future of even greater diversity, something in an era of globalisation we can all recognise, but more overtly experienced in a small nation state. The one connection to the past is a benign Indian woman who has worked at the hotel for 30 years and assures management that, yes, other people have died in the hotel over the decades.

Issues and eras

The nine scenes between the first and the last accommodate a vast range of characters, historical events and issues. In a comic scene set in the 20s, a housemaid, caught out in a hotel guest’s dress, is confronted by a nun and two policemen, little knowing that she’s adopted the role of a woman who has beaten her fellow maid and that the nun, in response to new legislation forbidding the abuse of maids, is following up on a reported crime. In 1935, a scene is built around a spiritualist who anticipates a coming war in the face of British indifference; in 1955, a famous filmmaker, P Ramlee, battles to make a socially conscious film without singing and dancing and focused on Malay culture.

In 1975, in an hilarious drug-fuelled farce (the wallpaper warps) a Eurasian transgender person, Brigid, is confronted with the Virgin Mary, giant walking penises and angels arguing for commitment to one gender or another. It’s revealed that the first sex reassignment operation in Singapore took place in 1971 and that by 1973 identity cards reflected the transition. But Brigid declares love for both her/his breasts and cock and is determined to be a different kind of ‘other.’ This passion is juxtaposed with the sudden appearance from a wardrobe — at the mention of God — of the nation’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, railing against men with long hair spoiling foreign investment in Singapore and opposing ambiguity in general. Brigid and the US Viet Vet who provided the drugs have sex, she mounts him, and in a segue we see them celebrating marriage.

Hotel, W!LD RICE, photo courtesy the artists and OzAsia 2017

Across generations: continuity & disruption

Occasionally, characters in one scene reappear in a later one. The perky aspiring film starlet of 1955 reappears, now devoutly Muslim, in 2005, travelling with her businessman son from Malaya, but Singapore is not what it used to be. Worse, post 9/11, her angry son is an easy target for over-zealous security forces and is arrested. Her grandson comments that although his father has no bomb, “the bomb is in the minds” of the Singaporeans. This was the one scene, that although painfully tense, lacked the telling extra dimension common to the others.

In 1945, a Japanese captain, Matsuda, is told by his senior officer that the army is leaving Singapore and that he can bring his son with him, but not his non-Japanese wife Sharifah. The separation is brutally painful, especially when we learn that Matsuda, in act of unexpected kindness, had rescued her from working in a “comfort station,” where women were forced into sexually serving Japanese soldiers. Her anger is unforgiving. In 1985, in Hotel’s most moving and emotionally complex scene, the son, Natsuo, nervous to the point of vomiting and struggling to practice his limited English, has returned to Singapore to meet his unsuspecting mother, now considerably aged and confined to a wheelchair and assisted by her English-speaking grand-daughter who translates for her into Malay. The barriers to communication are many, until Sharifah in anger, leaps up from her wheelchair and yells “Inu!” (dog) at Natsuo, and then a string of other words in Japanese that she explains, “feel like blood in my mouth.” He’s profoundly shocked, falling back as if hit, but persists, offering a recording of his father, who “wanted to come back,” singing for her. In a wrenching exchange Sharifah declares this will be their only meeting and, as he bows low before her, acknowledges him as her son, though she cannot forgive her husband. The full weight of the impacts of war and racism are conveyed in nuanced performances of awkwardness, stuttering hesitancy, misunderstanding, unleashed pain and provisional conciliation.

Another scene, set in 1995, plays out as a classic wedding farce awash with complications around Chinese and Indian intermarriage which, if difficult enough in themselves, are exacerbated by the Chinese bride’s decision to wear a sari for the second stage of the ceremony, to the unyielding resistance of her mother who walks out on the event, just when you expect accommodation. It’s a chilling end to an otherwise riot of contrasting characters — an overly accommodating Indian aunt, a stereotypical gay makeup artist, a sniping Chinese sister of the bride, the wearied father of the bride, an indifferent groom and his understanding mother who comments wryly to her Chinese counterpart, “Yes, the sari is a little too Indian.”

Hotel, W!LD RICE, photo courtesy the artists and OzAsia 2017

Close to home

In many respects, Hotel offers a conventional theatre experience, but provides evidence aplenty that with ambition and vision there is still life in an often tired model. With its two writers, two directors and 11 substantial episodes it’s akin to contemporary television series with their heightened creative teamwork and their appeal to sustained audience engagement. The OzAsia Festival audience met Hotel and its talented cast with unbridled enthusiasm, including the local Singaporean diaspora, some of whom were heard singing along with the national anthem and others, too long away from home, rumoured to have been surprised that the production could get away with the God/Lee Kuan Yew moment.

Although Hotel might not have addressed continuing constraints on democracy, including on the arts (read an interview with leading theatremaker and Director of the Singapore Festival 2014-17 Ong Keng Sen), it was nonetheless disarmingly frank on key matters and admirably culturally self-critical. As our own country increasingly inclines to authoritarianism and struggles to deal with expanded multiculturalism, Hotel’s Singapore feels close to home. OzAsia Festival Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell’s decision to program was bold, apt and timely.

–

OzAsia Festival: W!ld Rice Theatre, Hotel, writers Alfian Sa’at, Marcia Vanderstraaten, directors Ivan Heng, Glen Goei, set designer Wong Chee Wai, lighting designer Lim Woan Wen, multimedia designer Brian Gothong Tan, composer, sound designer Paul Searles, The Gunnery, costume designer Theresa Chan; Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide, 28-30 Sept

Top image credit: Hotel, W!LD RICE, photo courtesy the artists and OzAsia 2017

In our concern with the negative effects of colonialism, we often overlook the enrichment that cross-cultural intercourse can bring. Macau Days offers a glimpse of that enrichment by illuminating the history and mythology of Macau, a 500-year-old European outpost and the first European settlement in Asia. A collaborative work by visual artist John Young, author Brian Castro and composer Luke Harrald, Macau Days includes a book of the same title by Castro (himself of Portuguese, Chinese and English parentage) and Young (Chinese and French-Dutch). All are Australian residents, and both Castro and Young were born in Hong Kong which neighbours Macau. The exhibition demonstrates the human need for travel and migration in personal and spiritual growth.

The beautifully produced and illustrated trilingual book is itself an art object, comprising poems by Castro and Paul Carter inspired by Macau’s colonial history, an introductory essay by Art + Australia editor Ted Colless, and images of Young’s artwork. Castro’s delightful and darkly humorous poems, collectively entitled Macau Days: or Six Poems in Search of a Dish, bring to life six characters he has discovered who exemplify Macau’s history — the Chinese sea goddess Mazu (originating c 960, and whose name may have been the source of the name “Macau”), the Portuguese poet Luis Vaz de Camões (born c 1524), Chinese poet and painter Wu Li (born 1632, an early convert to Christianity following the arrival of the Jesuits), court artist and Jesuit Giuseppe de Castiglione (born 1688), Portuguese writer and Japanophile Wenceslau de Moraes (born 1854) and Portuguese poet Camillo Pessanha (born 1867).

Castro includes recipes that reflect Macau’s multicultural nature and invites readers to prepare their own dishes to recreate the character of Macau on the premise that food is emblematic of culture and identity. He researched his subjects closely and these recipes were evidently the favourites of the six characters — it’s as if we could enter their hearts and minds or become Macanese by eating these tantalising concoctions.

Mazu, Goddess of the Sea, John Young, Macau Days, image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

The visual component of the exhibition, John Young’s outstanding Macau Days series (2012), comprises several paintings in which images resembling photographic negatives or digital prints of old photos are overlaid with coloured abstract imagery. The figure of a woman in these paintings evocatively represents the goddess Mazu. A series of digitally reproduced historical photographs evoke the history of Macau with, for example, images of significant buildings such as Jesuit churches and a photo of Wenceslau de Moraes in Japanese garb with a small child. And there are texts chalked on paper painted with blackboard paint, as if lessons were being learnt (perhaps in a Jesuit school). These texts are personal musings, for example “to the ends of the world to find my anima,” “our souls meet here” and “absolutely foreign — see how I became.” Some of these chalk-on-paper works bear erasures and re-inscriptions, as if thoughts have been corrected. Young’s layering, corrections and juxtapositions symbolise the layering and juxtaposition of cultures found not only in Macau but throughout the world.

Luke Harrald’s meditative sound installation is a 21-minute tape loop of voices reading Castro’s poems in Mandarin, Portuguese and English. Depending on where you stand in the gallery, you hear each reader separately and quite distinctly. In the background are field recordings of splashing water, bells, street noises, voices and horses’ hooves evoking old Macau’s aural character. The whole exhibition is an immersive and enchanting experience, part history and part magic realism, and it could only be improved by adding servings from Castro’s menu.

The crucial point of the exhibition is that our subjectivity determines our response to colonisation, migration and cultural hybridisation. Of Young’s artworks, Castro writes: “Having studied Ludwig Wittgenstein/ you know that culture determines/ the way we see; that a person’s name/ is, has to be, the picture of a situation./ Doubled and tripled we crossed borders/ easily; but now the paranoia of ignorance/ has folded up your tapestry/ and it’s a DNA test for ancestry/ which supposedly clarifies how/ humanity runs in generations/ alongside insanity/ depending on the periodic flood/ that brings on the clash of blood.”

The colourful history of Macau shows how travel and migration are long-standing human traditions, precipitating enrichment and development. As Ted Colless puts it in his introductory essay: “In this spectral and sensual liquidity of Macau — a version of the city not so much groundless but ungrounded: a city (as one tourist brochure puts it) with no flora and fauna to speak of — borders become porous or ebb and flow, and the earnest chauvinism of identity politics can be supplanted by mashups and medleys.”

–

OzAsia Festival: Macau Days, artists John Young, Brian Castro, Luke Harrald; Migration Museum, Adelaide, 23 Sept– 8 Oct

Top image credit: Marienbad, John Young, Macau Days, image courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery, Hong Kong

In the 2017 OzAsia Festival two acclaimed theatre productions from Singapore — W!LD RICE’s Hotel and Checkpoint Theatre’s Recalling Mother — probe Singaporean history, identity and family interaction in vastly contrasting ways, one epic, the other intimate. Previously a British colony and then briefly part of the Federation of Malaysia, Singapore became a sovereign nation on 9 August 1965. Chris Reid spoke to members of both ensembles on 10 August, the day after huge National Day of Singapore celebrations.

Hotel, Wild Rice, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

W!LD RICE, Hotel

First staged in 2015, Hotel presents Singapore’s history from 1915 to 2015 through the interaction of a succession of groups of people in a room in a hotel not unlike the famous Raffles. Shown in two five-hour parts over successive nights, the play reveals Singapore’s turbulent history, rapid social and political evolution and diverse culture through the eyes of the play’s characters. I chatted with co-director Glen Goei and co-playwright Alfian Sa’at about the development of Hotel and its politically and socially charged themes.

Glen Goei tells me about the scale of the work: “It has a cast of 14 actors who play over 100 roles in nine languages including Japanese, Cantonese and Malay. There are two writers and two directors. Although an unusually long play, each scene is on average 20 minutes, very bite-size, very palatable, very accessible, like binge-watching… If you commit to the two parts, you will be rewarded because some characters re-emerge, older but wiser.” Set at 10-year intervals, the successive scenes reveal Singapore’s development in the context of world history in a text that is predominantly in English and a production strongly imbued with Western theatrical traditions.

A variety of families and groups occupy the hotel room, revealing Singapore’s ethnic and cultural diversity, highlighting the multiple traditions that constitute modern Singapore, rather than glossing over them. Alfian says, “We should not let any one identity try to dominate our understanding of the country and we should have a dialogue about our differences.” Glen adds, “Imagining we are one cohesive whole is unrealistic.” Noting that Singapore existed long before Sir Stamford Raffles established the British colony in 1819, he says, “Let’s celebrate differences. Singapore is a true melting pot… The Indigenous people who were here 500 years ago were the Malays, they were 100% but now form only 15% of the population.”

As in Australia, immigration numbers and the presence of foreign workers are issues in Singapore. Glen notes, “We are allowing 100,000 people in every year… The population is 5.6 million of which really only about three million are native Singaporeans — as in being born here — and that population isn’t growing.” Ethnic diversity and continuous immigration and emigration means that Singapore’s sense of tradition is in flux. Alfian thinks that “we are living in an eternal present and in a society that is quite amnesiac in a way.”

The Adelaide production will be Hotel’s international premiere, providing its makers with its first feedback from a non-Singaporean audience. Glen comments, “I think that Adelaide audiences will be pleasantly surprised at how their experiences will resonate with ours because of similar colonial histories and, right now, problems of immigration and race. I’m hoping Adelaide audiences will go away from Wild Rice feeling something profound. At the end of the day, the themes are universal.”

Alfian frames the key questions that Hotel asks: “What sort of society do we want to be: an open society or a closed one? How do we deal with difference within and outside of our borders? What are our responsibilities as global citizens? Are we aware of some of the privileges that we have? To borrow a line from revolutionary philosopher Frantz Fanon, what do we owe to support the wretched of the earth?”

Claire Wong, Noorlinah Mohamed, Recalling Mother, Checkpoint Theatre, photo Joel Lim courtesy OzAsia 2017

Recalling Mother

Recalling Mother is a highly unusual work for two actors who play themselves and their mothers from a script that, since the 2006 premiere, has been rewritten for each production in 2009, 2015 and 2016. The dialogues between mother and daughter reveal generational differences and the most recent iterations of the play reveal how the daughters have had to take increasing responsibility for their mothers as they reach old age, become dependent and when minds can fade. The play shows how Singaporean social and familial norms have evolved during the nation’s recent history, for example Noorlinah Mohamed’s mother never went to school while Noorlinah herself has completed her PhD.

I spoke to performer-writers Claire Wong and Noorlinah Mohamed about the play’s focus. Noorlinah says that, “Recalling Mother is not just stories of daughters and mothers; it’s also about our mothers, and we are discovering new things about them as they grow older. Recalling Mother is a durational performance of life [in which] I ask, how do I make meaning of this journey for myself.”

The play is intended in part to encourage inter-generational communication often made difficult by Singapore’s linguistic diversity. This is the case, says Claire, for themselves — her mother speaks Cantonese and Noorlinah’s Malay — and especially affects the relationship between people in their 20s and their grandparents. “Grandparents might speak Cantonese, but the young ones have been schooled in Mandarin because of government policies to standardise the Chinese language.” The Government’s Bilingual Policy encourages proficiency in English and an ethnic mother tongue, such as Mandarin, Malay or Tamil. Noorlinah adds, “people in their 70s and 80s communicate little with their grandchildren. Their worldview is very different because they think in the way they speak their language.” Both actors work with young people who, says Claire, “tell me that there is a great reluctance for their grandparents to talk about different parts of their lives, for example they lived through World War II and the Japanese occupation but will just not talk about it.”

Addressing the recurrent rewriting of their script, Claire explains, “we decided not to keep to the original because we were interested in connecting with the ‘now’ each time we performed it. It’s a living text: we write a new script each time, it’s like a journal. The performances are like pauses in our lives.” She adds, “we considered the question of whether we wanted to incorporate excerpts of the 2009 version which had been videoed, but eventually we used audio bits from earlier performances. There is a consciousness of a sense of documentation, which is verbatim, and of non-performance: we are recalling our mothers.”

The question and answer session at the end of each performance provides an opportunity for audience members to share their own experiences of family life. Claire says she and Noorlinah see “Recalling Mother as a continuous conversation. It was conceived as a conversation and it continues to be even after the formal conversation that we have presented in the theatre space is finished. We didn’t originally foresee the question and answer session as part of the play, but we realised from early incarnations how it opened up space for people to voice what they have inside.” Noorlinah adds, “people in Singapore don’t normally open up, but we have been surprised at how much they have. That has been very humbling for us.”

Recalling Mother has played in New York and Brisbane, and though it is about a culture very different from a Western one, Claire feels that, “the more specific [to the culture] the play is, the more real and authentic it is for the audience. There is a universality to it.”

–

Chris Reid spoke to Glen Goei, Alfian Sa’at, Noorlinah Mohamed and Claire Wong in Singapore courtesy of Culturelink and the Adelaide Festival Centre.

OzAsia Festival, W!LD RICE, Hotel, Dunstan Playhouse, 28-30 Sept; Checkpoint Theatre, Recalling Mother, Space Theatre, Adelaide, 22-23 Sept

Top image credit: Hotel, Wild Rice, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

If there has ever been a necessary moment for Australians to be ‘taken out of ourselves,’ to evaluate our cultural and political place in the world as geopolitical tectonic plates shift us away from the US, it is now. Once ‘outside’ we can open up to and appreciate cultures substantially different from our own, look back at ourselves and acknowledge the art growing here that tells us how Asian-Australian our culture has become, alongside and entwined with our European and Indigenous heritages. With an intensive program, at once accessible and provocative, Adelaide’s annual OzAsia Festival continues to temporarily relocate and enduringly reshape our collective imagination with intensive and seductive programming.

When we meet in Sydney prior to the launch of the 2017 program, I ask OzAsia’s Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell about the progression of his programming over his three festivals since 2015. He tells me that after “breaking down the fourth wall” with immersive contemporary Asian works (including visual and performance art) in his first festival, in his second he focused on works that commented on their countries of origin (including the strange cultural and economic relations between America, Japan and Korea in Toshiki Okada’s wonderfully absurdist God Bless Baseball), “along with a brushstroke picture of the city/rural divide” (as in the wildly funny and socially critical Chinese production Two Dogs, an exemplar of the merging of traditional and modern popular performance).

In his third festival, Mitchell says he’s “going in deeper with a large focus on very personal and intimate stories told from Asia and with more Asian-Australian collaborations, in the arcs of dance as well as in theatre.” As our conversation continues, it becomes clear that the ‘personal’ will be framed within mythology, history and gender as will a focus on artists who are setting the agenda for furthering 21st century Asian and global culture.

Next week we’ll survey collaborative Australian and other works in the festival’s program and, shortly after, the visual arts component. This week Mitchell and I focus on the major theatre and music components.

Until the Lions, Akram Khan Company, photo Jean Louis Fernandez courtesy OzAsia 2017

Akram Khan Company, Until the Lions

At first glance, British choreographer Akram Khan’s acclaimed Until the Lions, a dance adaptation of a story from the Mahabharata, seems an unlikely ‘personal’ tale. Mitchell explains, “It is a big work, with a big set, but it’s a particularly individual story. The creators, Khan and poet Karthika Nair, have focused on a story they convey from a female perspective about a princess, Amba, who is abducted by a general, Bheeshma, and she seeks venegeance.” Nair had gathered stories about often unacknowledged female characters from the Mahabharata in her book of poems Until the Lions, which became the title of her collaboration with Khan. In an unusual twist, Amba kills herself, is reborn and changes gender to defeat Bheeshma. Nair has explained the title: it’s based on an African saying about who gets to tell the story after the hunt — usually the hunter; but the tale is not properly told until the lions speak; as it should be for the women in the male-dominated Mahabharata.

Although British reviewers have praised the work for its adroit abstraction and use of symbolism, Mitchell says, “dance theatre is such a loose term, but Until the Lions is a narrative told through dance in 55 minutes. “As with a play, “you need to watch and decode to understand.” A YouTube trailer offers glimpses of an engaging blend of the literal and its abstraction, particularly in fight scenes.

Recalling Mother

Mitchell describes Recalling Mother as conversational performance but also as another very physically expressive work. Singaporeans Claire Wong and Noorlinah Mohamed are friends who explore their relationships with their non-English speaking Cantonese and Malay mothers, taking turns to play each other’s mother in mother-daughter dialogues. Mitchell tells me that when the work was first performed almost 12 years ago, the emphasis was on comedy and the language and culture-clash tensions “between tradition and Singapore’s slightly hybridised Western identity. The humour is still there, but the artists don’t remount the play so much as recreate it now that one of the mothers has dementia and the role of carer and a sense of mortality have entered and intensified the sentiment. The show runs for 75 minutes but with a Q&A which the artists see as part of it, because they feel audience members need to debrief about their own relationships with their mothers.”

In an interview, Noorlinah Mohamed said of Recalling Mother, “It is perhaps the first and only theatrical project, that when restaged, is always revisited as a new creation. The work is a living durational performance where life and art parallel and inform each other.”

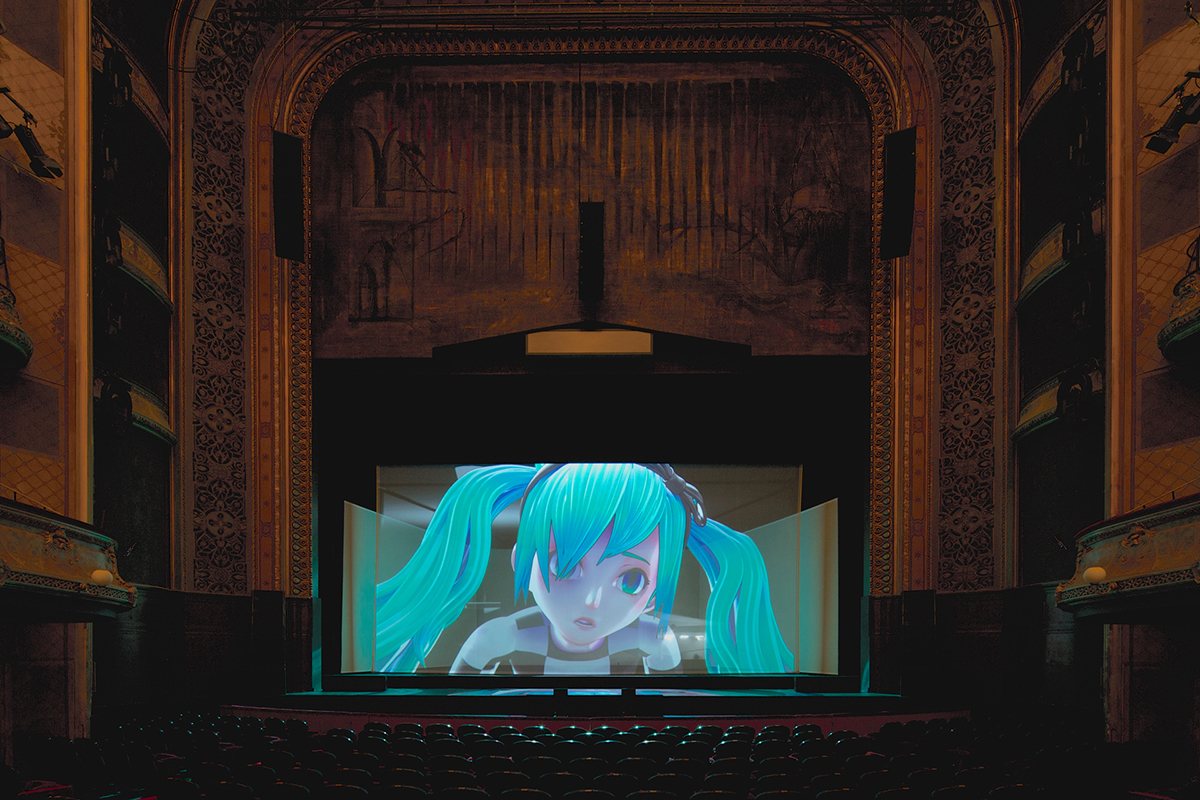

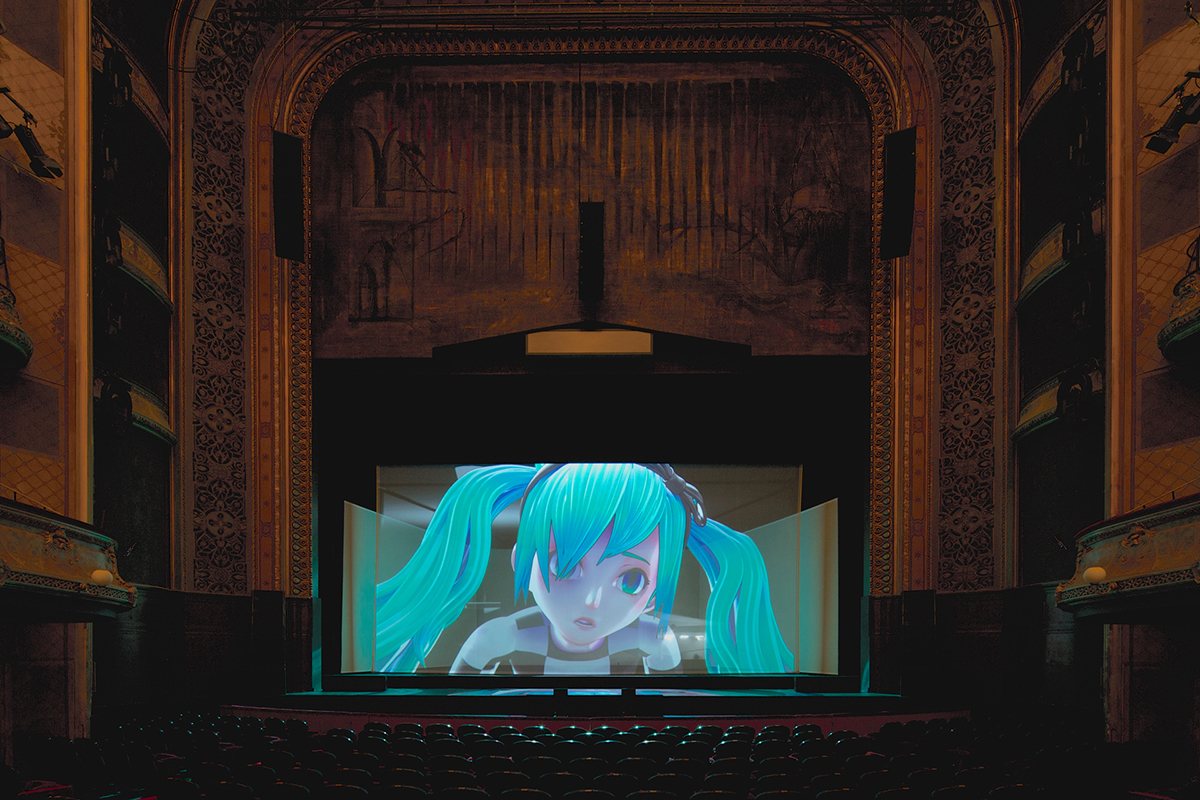

The End, Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, photo Kenshu Shintsubo courtesy OzAsia 2017

Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, Vocaloid Opera: The End

The sense of the personal might seem to evaporate when contemplating two works by a Japanese artist which feature non-human performers: one with a vocaloid (think singer + android) and a robot. Of Asian artists setting the agenda in performance, Mitchell sees Japan’s Keiichiro Shibuya, “with his bold sense of provocation,” as the standout exemplar. He has created The End, an opera for theatre without live singers or an orchestra for virtual pop idol Hatsune Miku. Mitchell says, “she is one of the biggest pop stars in the world. She has some 100,000 pop songs about teen love and relationship breakups, composed by professional teams but also by hardcore fans via purchased software. Shibuya had been a fan and when his wife, a leading fashion designer, died and he spiralled into depression, he latched onto thinking about the nature of death and how Miku will never die. He thought, ‘What if I go into her psyche and find out who this vocaloid is, loved by the world?’ So he asked the novelist, playwright and Artistic Director of chelfitsch, Toshiki Okada, to write the libretto and approached Louis Vuitton to design Miku’s outfits for a giant opera. It’s the most elaborate of her set-ups for an appearance and involves four screens and a mini-screen behind which Shibuya plays the music live.”

Mitchell notes that “When The End debuted Miku’s fans turned out: they were nervous, keen to support her doing opera, hoping she’d last the distance, but had faith in her and were very excited to see her dressed by Vuitton. It went to Europe last year, a bit outside her realm, but created a fusion of arts lovers and fans.” He does believe The End “has to be a dividing piece in terms of the operatic voice. However, the score and the libretto have all the hallmarks of great operatic tragedy and self-insight. At a time of the Australian Government review of opera, a decline in audience numbers and the large cost of the subsidy involved, we need to think about the artform and let it evolve; this work points a way.”

Skeleton, Ishiguro Lab, Osaka University, photo Justine Emard, courtesy OsAsia 2017

Australian Art Orchestra: Keiichiro Shibuya, Scary Beauty

Shibuya makes another appearance in OzAsia 2017 with Scary Beauty, again with a non-human performer — Skeleton, a singing robot with its own neural network — and, again, imagined as a large-scale work. But, says Mitchell, that would have taken years to develop, so the artist was commissioned to present a version of the work with the incisively adventurous Australian Art Orchestra, led by Peter Knight, as part of an afternoon of three discrete concerts featuring Shibuya, guzheng player Mindy Weng Wang and, in Seoul Meets Arnhem Land, Ecstatic Beauty, the pairing of Korean ‘street opera’ singer Bae Il Dong and Daniel Wilfred from the Wagilak clan in the Northern Territory.

Joseph Mitchell sees a widespread preoccupation with robots as workers and service providers as ignoring the rise of AI, which demands of us a better sense of what it is to be human; that, he thinks, can come through art and the challenges offered by works like Skeleton. This cluster of concerts should be a festival highlight, invoking living heritage and evoking possible futures.

Hotel, W!ld Rice, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

W!LD RICE, Hotel

The personal is given an epic dimension in W!LD RICE’s Hotel, 100 years of Singapore’s history performed over five hours. Mitchell describes himself as a slow decision-maker, but within minutes of seeing Hotel he knew he had to program it: “We have to do this, no matter what. It’s one of the best theatre works I’ve seen in the last few years and has never had a bad review. You can see it all at once or in parts and is a bit like watching a Netflix series — there are 11 stories of some 20 minutes each, with characters and incidents overlapping, characters ageing across 40 to 50 years and told through the lives of ordinary people — from British colonialism to the Japanese occupation, independence and the explosion of today’s queer culture.” The hotel is unnamed, but it’s easy to guess it’s Raffles and all that it has symbolised. Mitchell feels that, like Australia’s widely played Secret River, Hotel is a story that needs to be told. Read more about Hotel, Mitchell’s first large scale work for OzAsia, here.

Niwa Gekidan Penino, The Dark Inn

Although enamoured of earlier works by Kuro Tanino and determined to program him in OzAsia, the auteur’s most recent work, The Dark Inn, proved to be Mitchell’s ideal choice. “The early work was really ‘out there.’ Kuro’s a trained psychiatrist who has worked with a lot of people who don’t see the world the way we do, so he created theatre from their viewpoint. The sets were crazy, with strange dimensions: there were penises across the stage. I saw The Dark Inn in Kyoto last year and agree with people who think this is Kuro’s masterpiece. It won the Kishida Prize for Drama.

“A dwarf father and his tall son are travelling puppeteers booked to play in a country bathhouse but arrive to find a disparate bunch of characters who are not expecting them. In the kind of revolving, multi-level set Kuro’s famous for, with a Japanese bath, steam, inquisitive characters and odd conversations, the play is more about inner states of mind than a straight narrative.” Mitchell adds, “After appearing in major US and European festivals, this is Kuro’s first visit to Australia and is a great opportunity for audiences and those attending the Australian Theatre Forum during OzAsia to see new directions offered by this kind of work.”

Darlane Litaay, Tian Rotteveel, Specific Places Need Specific Dances, photo courtesy Indonesian Dance Festival & OzAsia 2017

Specific Places Need Specific Dances

The collaborative dance work Specific Places Need Specific Dances foregrounds personal desire. Darlane Litaay from Papua New Guinea and Tian Rotteveel from Germany, investigate “waiting in different places, sharing culture and exchanging daily habits” (program). Each visits the other’s home country out of curiosity, says Mitchell, “Darlane to experience Berlin’s underground club and dance scene, Tian to see traditional male garb and in particular the penis horn. To Western eyes, these can appear sexual and as empowering the male figure. There are readings you can take from this work about exchange, sexuality, queer culture and male identity. For me, this is a work which sits at the cutting edge of contemporary dance.” Two more artists, in their Adelaide premieres, confirm Mitchell’s commitment to dance that draws on tradition and local cultures while venturing in new directions.

Aakash Odedra Company, Rising

Aakash Odedra will perform a self-choreographed contemporary Kathak piece and works made for him by Akram Khan, Russell Maliphant and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Maggi Philips wrote of the performance at the 2015 Perth Festival, “Odedra’s presence and collaboration with an impressive list of contemporary choreographers delivered a sense of celebration awakened in a performance which gathered strength from tradition and experimentation alike, yet was humble and projected humankind as simply strange and remarkable in a world of mystery, beauty and pain.”

Eisa Jocson, Macho Dancer

Eisa Jocson, who has appeared in Performance Space’s Liveworks in Sydney and Melbourne’s Asia TOPA, performs her eerie, gender-bending solo work Macho Dancer, drawn from her personal observations of Filipino club dancers. She said in an interview in RealTime, “Macho dancing is performed by young men for both male and female clients. It is an economically motivated language of seduction that employs notions of masculinity as body capital. The language is a display of the glorified and objectified male body as well as a performance of vulnerability and sensitivity.”

I wrote of this striking performance in 2015, “Jocson becomes a young, gum-chewing male dancer passing though a series of telling phases in which he is variously proud, defiant, calculatingly erotic and sulky; at one point he stops dancing and withdraws into upstage shadow — a tease or a moment of existential doubt?”

We’ll tell you more about Joseph Mitchell’s third OzAsia Festival in coming weeks, but already I feel a sense of eager anticipation building around the prospect of entering the idiosyncratic worlds of Akram Khan, Keiichiro Shibuya, Kuro Tonini, W!LD RICE and Darlane Litaay and Tian Rotteveel, with their offers of opportunities to redefine art and self.

–

OzAsia Festival, 2017, Adelaide, 21 Sept-8 Oct

Top image credit: The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino courtesy OzAsia 2017

Two dance theatre works at this year’s OzAsia Festival attested to the form’s remarkable elasticity and varied, if not always lucid, methods of making meaning from the everyday.

The Record

Properly speaking, the first, 600 Highwaymen’s The Record, ought not to have been in the festival at all. Its creator-directors are Americans Abigail Browde and Michael Silverstone, and the work doesn’t otherwise explicitly engage with Asian culture or themes.

I was, nevertheless, grateful that OzAsia Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell’s enthusiasm for The Record overrode any parochialism that might otherwise have kept it out. It’s a deeply humane and affecting work, one that subtly bonds its non-professional performers and audience as it seeks to codify the complex rituals of human interactions between strangers by means of a stripped back, gestural aesthetic. In the process, our position as viewers is inverted as the performers—dressed much as we are in ordinary chinos, shirts, trainers and the like—stare expressionlessly out at us.

In The Empty Space, Peter Brook famously noted that all that is needed for an act of theatre to take place is for someone to walk across an empty space while being watched by another. So begins The Record. A single performer—in this case, a schoolgirl in uniform—walks to the centre of Chris Morris and Eric Southern’s austere set: a rectangular strip of unvarnished wood overhung with a long, white piece of cloth behind which a soft light rises and falls in intensity throughout the work’s 60 minutes. After what seems an interminable stretch of stillness and quiet, the girl strikes a series of classical poses—for example, back leg dipped, front leg powerfully jutting, one fist raised in the air—of a kind that will be repeated and extended by the rest of the performers.

The poses have the effect of heroicising the everyday, just as the work more broadly foregrounds the ordinary, throwing its performative aspects into sharp relief. As the poses are struck before dissolving into tableaux, cellist Emil Abramyan, placed to one side of the wingless stage, picks out pizzicato chords, later performing elements of Italian composer Carlo Alfredo Piatti’s Caprice No 2, his bow playing introducing a warming melodiousness. Brandon Wolcott’s electronic score, played live via a laptop and combining drones, crackles and machine- and speech-like disturbances, provides additional layers of ambient sound.

The performers who join the schoolgirl—gradually at first, singly and in pairs, then in long, dizzying files towards the finale—comprise a stunningly diverse group (perhaps this alone is justification enough for The Record’s inclusion in a cross-cultural arts festival) made up of 45 people selected from the community. Together, they form a sort of living document of the vastly differing ages, nationalities and body types represented here, at this time. There’s an Adelaide Airport worker in hi-vis shirt and dark pants; a young, heavily pierced woman in pale makeup and gothic dress; a slim Chinese-Australian in her 20s; and children of both sexes in casualwear or long, animal-patterned pyjamas. We often hear, and it’s true, that our stages fail to reflect the ethnic and cultural diversity with which our city streets teem; The Record spectacularly corrects this imbalance, and in a way that feels quietly revelatory.

The performers, each of whom rehearsed individually and had not met each other prior to the first performance (the one I attended), frequently watch us in a gently probing exchange that calls attention to our own heterogeneity and status as strangers to one another who are, nevertheless, intimately linked by time and place. Those close-quarters, sometimes long-held gazes, as well as the moments of physical connection between the performers—pugilistic fists compassionately drawn back, hands and falling bodies briefly held, as in a trust exercise—accrue a tremendous emotional force, especially as they counterpoint the increasing mass of bodies and activity on stage. (At various points, multiple performers jog around the perimeter of the space, a reminder perhaps of the frenetic pace of life outside the theatre.)

Eventually, most of the performers disperse, leaving a small group upstage that includes, at the last, the two musicians, a low wash of sound playing out as Wolcott leaves his computer. Finally, just one woman remains. She moves downstage in her plain clothes as far as the seating bank will allow, looking, somehow, less lonely than the schoolgirl had, at peace with herself and the world. I want to hug her, or for her to reach out and touch me. Only this final, longed-for gesture is withheld in a work that is exceptionally and movingly generous.

As If To Nothing

Not to be confused with Craig Armstrong’s 2002 ambient electronic album with the same title, City Contemporary Dance Company’s As If To Nothing proved an altogether more mixed experience. Founded in 1979 by longtime Artistic Director Willy Tsao, the company has toured extensively internationally, its more than 200 productions to date reflecting trends in Chinese contemporary dance as well as, latterly, the vibrancy of post-Handover Hong Kong, where the company is based. As If To Nothing has been around since 2009, and it’s tempting to suggest the production’s age accounts, at least in part, for its slight tiredness (Brook again: “about five years is the most a particular staging can live”).

Sang Jijia’s set is a vertiginous white box. Its floor is faux-marble, polished and smooth. Within it resides both a smaller, narrower box on wheels, like a caravan or food vending truck but reminiscent of a scaled-down modern apartment in its sharp, white minimalism, and a section of wall into which, at one end, a full-size table on casters has been embedded. Cut into the box and wall segment are doorways and glassless windows through which the 14 performers—both male and female, each physically powerful and drably attired in loose, grey slacks, dresses and t-shirts—variously protrude faces and limbs.

The choreography, again by Jijia, lightly reflects the influence of mentor William Forsythe (Jijia spent four years with Forsythe’s Dresden-based company, returning to China in 2006) in its—not always cohesive¬—melding of the abstract and representational and its incorporation of technology and the spoken word. As If To Nothing’s structure further recalls Forsythe’s work in that it’s broken into eight segments—delineated, sometimes untidily, by blackouts—which both repeat and subtly evolve the obsessively enacted, tic-like gestures of each previous vignette.

The constantly shifting set and relentless kineticism of the dancers, all framed by the projection onto the walls and box of Adrian Yeung’s live video capture—sometimes delayed to disorientating effect, often freakishly distorted or punctured by gaps—is intended to invoke the slippery unreliability of memory. But it was, for me, the work itself that remained fundamentally muddled. Without subtitles, little sense can be made of the dancers’ exhortations, and I was left puzzled by the frequent manipulation of a small section of the box, repeatedly slid out and back like a desk drawer.

For all its technological saturation, too, some of the vignettes, such as a duet between a male and female dancer, feel oddly conventional, even trite. The video projections, though competently handled by Yeung, are unimpressive in themselves and further suffer from the work’s dysfunctional logic, which reduces them to empty spectacle. Only Dickson Dee’s insistently percussive live score, featuring industrial noise, arpeggiated piano and nightmarishly altered everyday sounds like clock ticks and alarms, was able to sustain my curiosity.

–

2016 OzAsia Festival: 600 Highwaymen, The Record, creators, directors Abigail Browde, Michael Silverstone, music Emil Abramyan, Brandon Wolcott; Space Theatre, 21-24 Sept; City Contemporary Dance Company, As If To Nothing, set design, choreography Sang Jijia, video design Adrian Yeung, music Dickson Dee; Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre, 22-24 Sept

Top image credit: The Record: Adelaide, 600 Highwaymen, OzAsia 2016, photo Claudio Raschella