When I graduated from art school, there was a lot to be part of in Sydney’s art community — a packed itinerary of new ARI shows opening on weeknights and art events on Friday and Saturday nights. Things feel radically different five years on. Gutted by funding attrition, gentrification and the hardships associated with managing Sydney’s ever-climbing living costs, the city’s art community lacks just that: structures for a community, like a hub and a reliable itinerary of events. In this picture of decimation, PACT Salon is an important addition: it promises an after-dark art party that’s more experimental, more inclusive and more grassroots than the Museum of Contemporary Art’s ARTBAR. The Big Bounce, the first night of the quarterly series in January, made good on that promise; its curator, Matt Cornell, a dancer, created a loose night of happy, shared energies — a dance class, compelling conceptual performances, cheap drinks — combining smart art-thinking with party vibes.

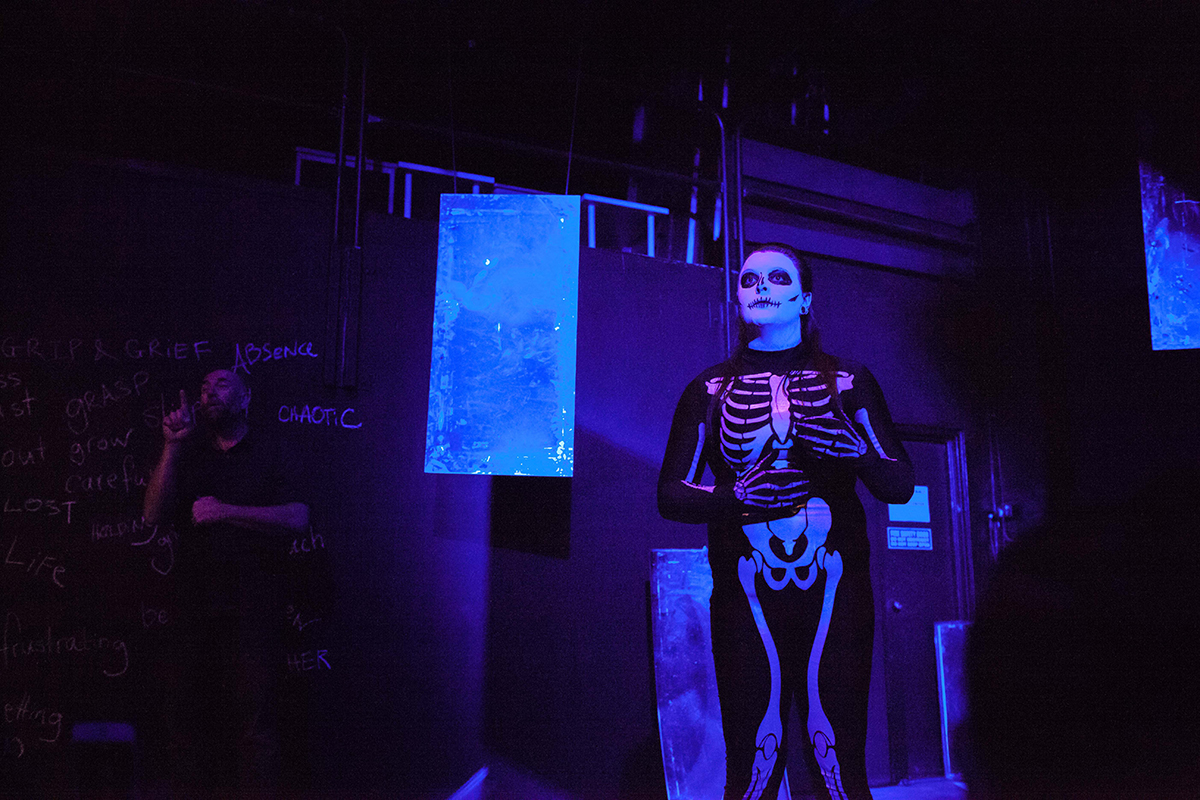

Skeletons and Self-Portraits was a more earnest affair. Though the promotional material spoke of a somewhat scattered constellation of subjects — all women artists, feminism, mental health, identity defined against others’ perceptions, a masquerade costume theme — the real, albeit undeclared, point of unity was an exploration of the identities of artists with different physical and invisible disabilities. Curated by writer, actor and motivational speaker Emily Dash, this was a night of monologues (Cheryn Frost’s Confessional), performance (Georgia Cranko’s On Grip and Grief), solo dance theatre (Kay Armstrong’s The Last Half), spoken word and pop performances (Jessica Wiel’s song “Innocence; Addicted; Feelings,” among several others by the artist) that focused on what it feels like to be a person with a disability in a careless society.

Confessional, Cheryn Frost, Skeletons & Self-Portraits, PACT, photo Tiyan Baker

Skeletons and Self-Portraits made me think of Stella Young, the deceased activist and writer, who insisted with sharp, nimble humour that her body was not disabled — that this notion was constructed by a callous, neoliberal society without the services or inclination to include all its members. In focusing on how big-picture injustice structures individual prejudice, Young opened up a cultural conversation about what a society that prioritised support needs might look like. Skeletons and Self-Portraits also made me think of a likeminded figure in the art world, the UK’s Claire Cunningham (read RealTime review), who became a dance artist after realising that the field needed new aesthetic perspectives that moved away from the able-bodied consensus: that she could take her crutches and use them to find a fresh physical vocabulary for the stage.

These attitudes were not evident in Skeletons and Self-Portraits; perhaps its aim was more about merely giving curatorial control to those who are often invisible in the art world. I was a little perplexed by the fact that the most ‘contemporary art’ aspect of the program, zin’s interactive Glitterbox (a huge glowing cube in which audiences choose their favourite song to dance to in a storm of glitter), was malfunctioning after adaptations were made following its first outing at Sydney Festival, and seemed thematically distant from the night’s other works. And I was ethically troubled by a work by Louise Kate Anderson. Billed as an installation to confront mental health stigma with audience members able to ask the artist anything about herself, it detoured from personally-framed conversations toward something of a DIY therapy event in which declarations about deeply complex issues were made and diagnoses offered with seeming authority and without professional expertise. It worried me that giving over a part of the event without clear curatorial guidelines resulted in misinformed (though well-intentioned) discussions that provided mental health advice from the artist and audience members without considering the experiences and safety of those present.

Glitterbox, zin, Skeletons & Self-Portraits, PACT, photo Tiyan Baker

As a community art event premised on self-expression and self-representation, Skeletons and Self-Portraits worked best as a platform for those who still often don’t have one. The night’s most interesting flashes of insight, though incidental, spoke to the possibilities of an art world that foregrounds access and inclusivity. First, the event’s Auslan translator, Sean Sweeney, struck me as the strongest performer: he was focused, present, connected, emphatic when called for and subtle at other moments. And second, Emily Dash’s videos of her own spoken word poems, I Am Not a Work of Art and The Cards I’m Dealt, featured closed-captions with functional descriptions like “music continues.” This made me wonder about the prospect of video artworks that leave behind sound altogether and describe fictitious audio elements, for viewers of all abilities — and on a level playing field — to imagine themselves. In these two moments, Skeletons and Self-Portraits inadvertently opened up two unexplored rivers of communication and thinking for disability arts in Australia. The usual audience of artists and followers seemed largely absent, suggesting that the artistic conversation didn’t reach as widely and effectively as it might have, but despite the program’s shortcomings PACT managed to open up its doors to a clearly underserved sector of the art-going community.

–

PACT Salon #2, Skeletons and Self-Portraits, curator Emily Dash, PACT, Sydney, 29 July

Top image credit: Georgia Cranko, On Grip & Grief, Skeletons & Self-Portraits, PACT, photo Tiyan Baker