The key to Ambulante is found in its title—it’s a festival that travels, showing films in multiple locations within Mexico City and currently, the states of Oaxaca, Chihuahua, Baja California and Jalisco. Between March 23 and April 6, committed patrons trekked across the megatropolis of Mexico City—Distrito Federal, or DF, for those in the know—to watch documentary films in multiplex cinemas, public parks and plazas, arts centres, university campuses, the historic Cineteca Nacional, museums, a metro station and even the national Senate building.

Founded by Hollywood’s Mexican darlings Gael García Bernal and Diego Luna, 2017’s Ambulante featured a program of hundreds of films from around the world, with a particular focus on content from Latin America. In announcing the dates in October last year, Bernal promised that the program would be organised around social justice themes, to raise awareness and inspire solutions to the struggle against corruption and impunity in his native land. Five months and one Trump win later, at the opening of the festival under the stars at the city’s hallowed Monument to the Revolution, Luna said, “2017 looks to be a difficult year not only for Mexico, but for the whole world and we here have to rethink many things and the documentary can help us do that.

“While we have to rethink our relationship with the United States, it also reminds us that today more than ever we have to see the South. We all have to establish bridges and reconnect with Latin America, because it seems that we forgot that we belong to something bigger.”

The festival programming is extensive, with films grouped under the headings of general programming; Por la justicia, Documentales Mexicanos, Ambulante más allá (documentaries by young directors), Sonidero (music documentaries) and the Ambulantito children’s program.

The cycle Ambulante por la justicia spanned screenings, fora, talks and debates and explored questions of authoritarianism and inequality, ranging across Eastern Europe (The Moscow Trials, Milo Rau, 2013), South Africa (The Gugulethu 7, Lindy Wilson, 2000) and the United States (the classic The Thin Blue Line, Errol Morris, 1998) to shed some light on Mexico’s extensive problems. The program included the highly acclaimed and domestically very popular Presunto Culpable (Presumed Guilty; Roberto Hernández and Geoffrey Smith, 2008), which follows the process of exoneration of a man imprisoned for a crime he didn’t commit. It was produced by his lawyers, Layda Negrete and Roberto Hernández.

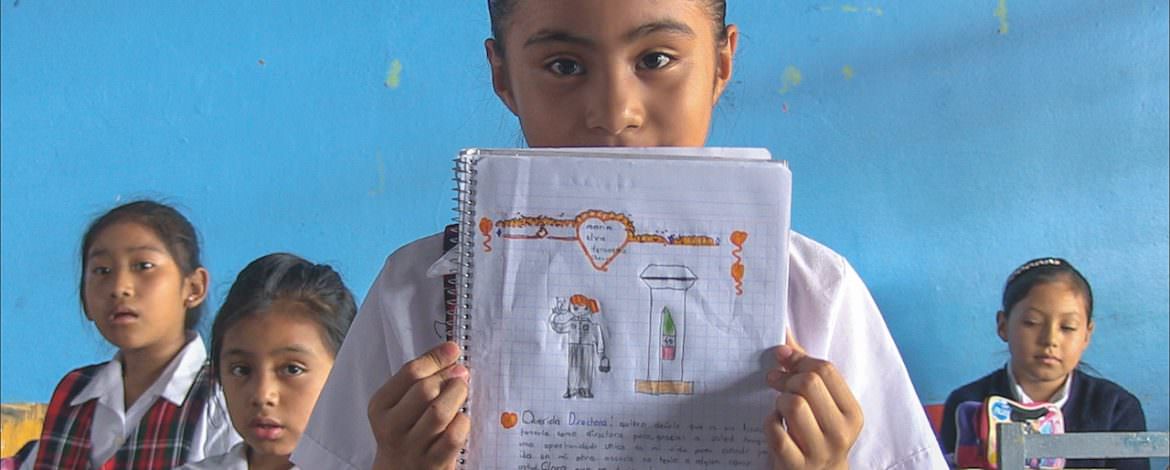

In the Ambulante más allá series, new directors who may lack the tools and opportunities for filmmaking are provided with training and funding by the festival. Portate Bien (Behave Well, Omar Zamudio) tells the story of primary school teacher María Elva Hernández, who after a 37-year career, is forced to leave her profession in the district of Chilpancingo, Guerrero, due to her participation in protests which have raged in rural locations across the country for the past two years against education reform proposed by President Enrique Peña Nieto.

Portate Bien is one of several films in the program set in the state of Guerrero, and there are certainly many stories to tell from this place right now. Guerrero is home to the Ayotzinapa rural teachers’ college from which 43 students went missing on September 26, 2014. Remains of two of the students have since been found and identified and drug cartel, police and government complicity in the kidnapping of the 43 is certain.

The Ayotzinapa case framed the content for the documentary Guerrero, made by French director Ludovic Bonleux and premiering at Ambulante. Through the eyes of three local activists, Bonleux shows the daily struggle against forgetting and complicity for so many in Guerrero where the drug war and state impunity have all but shut down the possibility of systemic justice for those who have lost family members to kidnappings and extrajudicial killings. Communities in the state capital of Chilpancingo have formed their own community policing units as well as expeditions to exhume and identify the human remains that riddle the mountainsides, casualties of the so-called “narcogobierno” which translates roughly as “drug dealer state,” referring to the entwinement of political corruption and drug cartels in the governance of the territory.

Mario, one of Bonleux’s activists, is heard saying to a young boy joining the expedition that he is an “exhumador del futuro,” a future exhumer of bodies. It’s a pedestrian moment, shocking in its ordinariness—as though this is the work of generations, and digging up the bones of murdered countrymen is the brightest honour a young boy can expect.

I went to see Guerrero at a multiplex cinema in the financial heart of the city, where Bonleux held a question-and-answer session after the film had screened. I was attending with a Guerrerense photojournalist, Jorge Dan López.

It felt surreal, as it often does when reminded of Mexico’s endemic violence and impunity, to be watching this story from inside the bubble of the DF, widely considered to be a zone of relative tranquility and prosperity in contrast to the crime and poverty and violence so prevalent in the rest of the country. Jorge felt this more bluntly than I did, saying as we snuck out halfway through the Q&A, “Well, that was just for the Roma-Condesa-Polanco set [in the city’s hip, rich neighbourhoods] to feel edgy and continue to do nothing.”

A mobile film festival may not be able to bridge audience divides like that but, in bringing the most worrying of Mexico’s ills to the heart of the city in the safest possible fashion, it might begin a conversation. In this and many other ways, Ambulante 2017 continues to fulfil its founders’ dreams of awareness-raising and solution-building—the highest callings of documentary film.

–

Ambulante 2017, Mexico

Top image credit: Ambulante Film Festival, 2017