“If you have the ability to create the visual language in which you’re speaking from the ground up, who can say no to that?” asks Denah Johnston, curator of Always Something There to Remind Me, a selection of 16mm experimental shorts from Canyon Cinema that recently screened at ACMI in Melbourne and Revelation Film Festival in Perth. Made by women in the US between 1958 and 2015, the technically, stylistically and thematically diverse films point to the breadth of that period’s avant-garde cinema. Out of this diversity arises Johnston’s interest in the nexus between women and representation, and together the films explore agency, social expectations and the gendered gaze.

Canyon Cinema is a collectively-run distribution company that archives independent films. It started in 1961 with informal screenings projected on a sheet hung in the backyard of the archive’s founder, filmmaker Bruce Baillie, in Canyon, California. Jack Sargeant, Program Director of Revelation, feels the new program of Canyon Cinema shorts “show the importance of the archive and of the curatorial voice, but more than this, they reveal the importance of individual filmmakers who pursue their own visions.”

Kristy Matheson, Senior Film Programmer at ACMI, echoes this motivation to bring rarely seen material to Australian screens. “In terms of a local context, I think it’s essential for female storytellers to be able to access a diverse array of works and this program did just that,” she says. “The range of storytelling devices and techniques shows a great range of work that I would hope inspires female storytellers but most importantly opens up the scope for all viewers to the ambitious and free-ranging scope of female voices.”

New cinematic languages

Johnston explains that she curated this program to highlight how women filmmakers have played with the accepted storytelling language of cinema. “There is such a vast freedom in the form. Obviously they’re not all traditional narratives with three-act structures, and I think that taking a film out of those constraints really works well for a lot of the filmmakers. To make experimental work in the first place you’re already making a conscious and aesthetic decision to step out of the narrative.”

The earliest film is Sara Kathryn Arledge’s What is a Man? (1958), started in 1951 but only completed after her release from psychiatric treatment. It’s a collection of bizarre scenes exploring gender roles, starting with Adam and Eve and moving through to modern mannequins. These are humorous, but also affective, with an emphasis on word play, like the nonsense uttered in the “psy-cry-atrist’s” office.

Sharon Couzin’s Roseblood (1974) illustrates cine-dance, centring on the performance of Carolyn Chave Kaplan. Kaplan’s hypnotic movements are interspersed with a surreal, fragmented series of symbols — flower, knife, eyes, hands. Repetition makes these everyday objects strange, and the kaleidoscopic images, dizzying pace and jarring music produce a mysterious and tense film. This is the most lyrical of the shorts, visually enthralling but also decisively and frustratingly abstruse.

Dorothy Wiley’s Miss Jesus Fries on Grill (1973) invokes a different kind of hypnotic meditation, starting with a newspaper detailing the violent death of Miss Jesus, who was thrown onto a grill when a car ploughed into a restaurant. The narrator muses over this horrifying accident as she tends to her baby, bathing, feeding and watching it fall asleep. Her actions are intimate and also palpably everyday, so different from the very unusual and public accident, and the film is immensely disquieting.

Take Off

Women, through women’s gazes

Three of the films interrogate the idea of women as objects, subverting the scopophilic gaze, a psychoanalytic theory popularised by feminist filmmaker and academic Laura Mulvey in 1976. In a defiantly radical political framework, JoAnn Elam’s Lie Back and Enjoy It (1982) aggressively questions the ways women are represented on screen by men, via a dialogue between a female and a male filmmaker. The dialectic takes priority over image here, which is mostly a flickering close-up of a woman’s face from a black and white pornographic film, distorted through looping, reversing, speed and exposure. In Removed (1999), Naomi Uman also edits a porn film, using nail polish and bleach to erase the female body. The fantasy becomes uncomfortably empty and decisively unerotic. Uman’s film comments on female performativity, in porn and in society, reflecting how identity is manufactured through societal conventions. This is echoed in Gunvor Nelson’s Take Off (1972), which also subverts the male gaze and conventional representations of women. She documents Ellion Ness, a famous burlesque performer, as she stages a striptease, which is conventional until she finishes undressing. When the act should be over, she continues the process in what becomes a surreal disassembling of her body. Ness reduces herself to her parts, as revealed to her expectant audience, but is gleefully in control as she discards the layers.

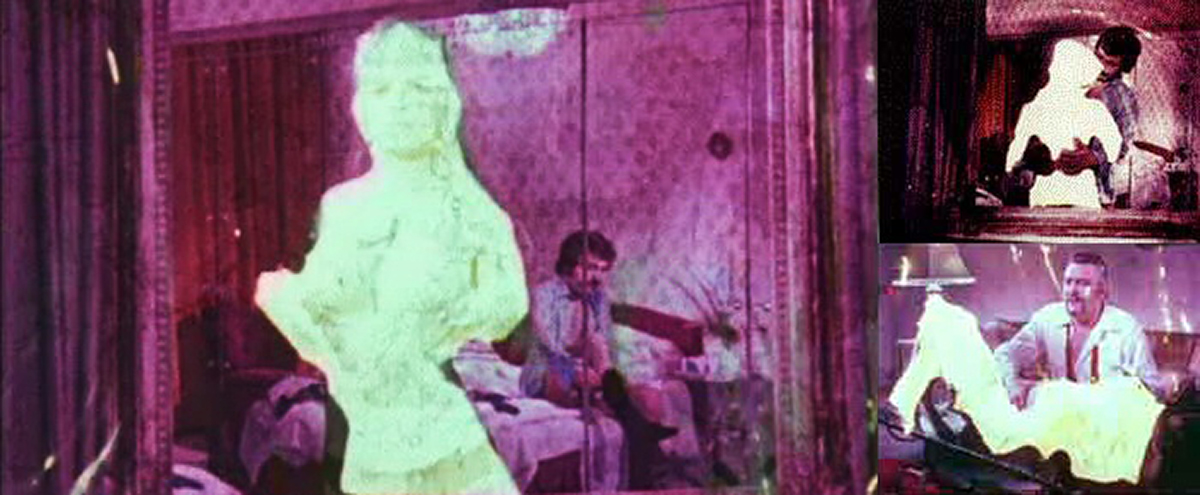

Chronicles of a Lying Spirit (by Kelly Gabron) (1992), directed by Cauleen Smith, also explores the fabrication of identity, specifically through the lens of her experience as a black woman. An example of Afrofuturism, the film layers time, space and history in following the imagined life of Smith’s alter-ego Kelly Gabron. There is a dual-narration from Gabron and a male voice discussing her in the third person, and the entire story is repeated, prompting a consideration of the instability and unreliability of history.

Removed

Collaborative context

Many of the works were collaboratively made and led to further collective activities. Kate McCabe founded the art collective Kidnap Yourself in the town of Joshua Tree, where she discovered inspiration and a creative community. The apocalyptically themed You and I Remain (2015), by McCabe and the collective, is part of the ACMI program. The filmmaker has remarked elsewhere that “you will find more females here behind the camera directing than in the commercial film world and that’s one of the many reasons that field [of experimental film] is vibrant and lush with ideas. The filmmakers I love from the 60s and 70s were breaking new ground.”

JoAnn Elam was also a founding member of Filmgroup (now Chicago Filmmakers) in 1973, which still holds weekly screenings of experimental work. Also in Chicago, Couzin cofounded the Experimental Film Coalition, of which she was president from 1983 to 1988. Some artists collaborated with friends, notably Nelson and Wiley, who made their award-winning first film Schmeerguntz together in 1965, with Nelson revealing that “Dorothy and I needed each other to dare to do it!”

The works are all shaped by socio-cultural discourse and social and professional opportunities offered by second wave feminism, and Johnston draws a comparison between the political consciousness of women filmmakers in the 1970s and today, saying, “right now, I feel like it’s on.”

You and I Remain

Local parallels

Tracing these films, there emerge parallels in Australian cinema history, where there was a surge of women filmmakers in the 1970s. Significantly, there was structural support for this, including the Women’s Film Fund (1975-1990), the Experimental Film Fund (1970-1978) and the Sydney Filmmakers Cooperative (1970-1986). There were also collectives like the Sydney Women’s Film Group (1971) and the splinter group Feminist Film Workers (1978) and events like the International Women’s Film Festival (1975).

If much of this government funding has ceased, or at least changed significantly, there continues to be critical — and importantly, public — interest in women filmmakers, with film festivals now providing the backbone of structural support. There are dedicated festivals like For Film’s Sake and Stranger With My Face Festival, which provides mentorship for women developing genre features, while OtherFilm has held several exhibitions and festivals of avant-garde work in Brisbane and at Gertrude Contemporary in Melbourne. Jack Sargeant notes, “this isn’t to say that there shouldn’t be more spaces, more funding or whatever, but there are people making and exhibiting works, so, while the situation could always be improved, I don’t see it as entirely bleak either.”

–

Always Something There to Remind Me, Canyon Cinema retrospective, curator, Denah Johnston, presented by ACMI and Revelation Film Festival, ACMI, Melbourne, 5 July; Perth, 9-18 July

Kate Robertson is a cultural critic with a PhD in Art History & Film Studies, and has written about arts and culture for The Atlantic, Vice, Marie Claire, i-D, Junkee, Overland, 4:3 and Senses of Cinema.

Top image credit: Chronicles of a Lying Spirit