Drawing heavily on pop culture and science, Gabrielle Nankivell’s Split Second Heroes conceives of the visible colour spectrum as a science-fictional site of personal struggle and self-discovery. Unusually for a work of contemporary dance — even one that leans towards Pina Bausch-like dance-theatre, if without its multivalent meanings — the bodies on stage represent emotionally distinct characters.

There is Black (Nankivell), a risk-taking sort with a penchant for danger and things that go fast (racehorses, sports cars). There is White (Luke Smiles, also composer and sound designer), an astronautical engineer, locatable perhaps on the autism spectrum by way of his awkward sociality and repetitive behaviour. And there is Grey (Vincent Crowley), achromatic narrator and intermediary, who relates, in the familiar but detached manner of a TED-talk speaker, the unlikely love affair that blooms between his seemingly antithetical counterparts.

We meet Grey first, as monochromatic as Benjamin Cisterne’s set in pallid, jacketless corporate wear and sneakers. Encircled by floor lights, he strides to a sort of rostrum-cum-control panel — two vertically-stacked industrial packing crates — from where he is able to stop and start the dancers, and even, with both a prismatic cube and joystick-like device, manipulate their movements and placement in the space.

Split Second Heroes, photo Chris Herzfeld Camlight Productions

Black and White, their distance at first conveyed in highly individualised and expressive solos, gradually converge, Grey describing their depolarisation in terms both whimsical and (pseudo-)philosophical. Each milestone in the relationship — tracing a path of Black’s emotional softening and White’s flight from routine — is marked by Grey’s producing of a representative toy or Lego sculpture (or, in one case, a functional Polaroid camera).

There is a sense at first that the trio, even the ostensibly neutral Grey, are in competition (for dominance of the spectrum?), for example running laps of the space following a rocket launch-style countdown. Black’s athletic, combative choreography is a blur of martial arts-style kicks, blocks and strikes. White’s movements are jerky and robotic, defensive rather than belligerent. Gradually, though, various accommodations are reached, Grey ultimately withdrawing to a place of objectivity, Black and White becoming partners rather than rivals in the intergalactic adventure first signalled by the work’s opening countdown. “I will miss Black and White,” says Grey, as though speaking — not entirely lamentingly — for a broader loss of the old, inflexible certainties.

As in previous collaborations between Nankivell and Smiles, most notably School Dance (2012), Split Second Heroes is rich in Gen X nostalgia. Smiles’ score, making effective use of multiple stereo channels, recalls early video game music, while the pre-digital moment is also evoked by the centrality of the Polaroid camera and Grey’s props (Lego, the arcade-style joystick, even the cube with its Rubik-like colouration). It was, substantially, the 80s too that gave us the figure, captured by Smiles’ White, of the nerd as (anti-)hero.

Split Second Heroes, photo Chris Herzfeld Camlight Productions

It’s a pity then that Nankivell’s text — rather flatly delivered by Crowley — proves frustrating. Though seamed with a non-scientist’s enthusiasm for the workings of the physical world, it too often comes off as trite rather than profound (I kept thinking of what the philosopher Daniel Dennett has dubbed “deepities” — statements that, on one level, are true but trivial and, on another, sound important but are essentially meaningless).

Grey’s control panel is similarly misconceived, too small and fiddly to register fully in each moment, and strangely causally inconsistent — sometimes the pressing of a button or moving of the joystick seems to do something, for example, trigger a piece of music or choreographic shift, and sometimes there’s no obvious effect.

More successful is Will O’Mahony’s dramaturgy, which effectively centres the work’s constituent parts and provides a stronger narrative through-line than seen in much contemporary dance with its discontinuous performance ideas. Perhaps this in itself is a kind of nostalgia, a return — both pleasurable and faintly unsatisfying — to the privileging of story over idea and image.

–

Gabrielle Nankivell, Adelaide Festival Centre & inSPACE, Split Second Heroes, concept, direction, text, choreography Gabrielle Nankivell, performers Vincent Crowley, Gabrielle Nankivell, Luke Smiles, score, sound design, interactive software design Luke Smiles/motion laboratories, dramaturgy Will O’Mahony, set, lighting design Benjamin Cisterne; Space Theatre, Adelaide, 27-29 July.

Top image credit: Split Second Heroes, photo Chris Herzfeld Camlight Productions

If there has ever been a necessary moment for Australians to be ‘taken out of ourselves,’ to evaluate our cultural and political place in the world as geopolitical tectonic plates shift us away from the US, it is now. Once ‘outside’ we can open up to and appreciate cultures substantially different from our own, look back at ourselves and acknowledge the art growing here that tells us how Asian-Australian our culture has become, alongside and entwined with our European and Indigenous heritages. With an intensive program, at once accessible and provocative, Adelaide’s annual OzAsia Festival continues to temporarily relocate and enduringly reshape our collective imagination with intensive and seductive programming.

When we meet in Sydney prior to the launch of the 2017 program, I ask OzAsia’s Artistic Director Joseph Mitchell about the progression of his programming over his three festivals since 2015. He tells me that after “breaking down the fourth wall” with immersive contemporary Asian works (including visual and performance art) in his first festival, in his second he focused on works that commented on their countries of origin (including the strange cultural and economic relations between America, Japan and Korea in Toshiki Okada’s wonderfully absurdist God Bless Baseball), “along with a brushstroke picture of the city/rural divide” (as in the wildly funny and socially critical Chinese production Two Dogs, an exemplar of the merging of traditional and modern popular performance).

In his third festival, Mitchell says he’s “going in deeper with a large focus on very personal and intimate stories told from Asia and with more Asian-Australian collaborations, in the arcs of dance as well as in theatre.” As our conversation continues, it becomes clear that the ‘personal’ will be framed within mythology, history and gender as will a focus on artists who are setting the agenda for furthering 21st century Asian and global culture.

Next week we’ll survey collaborative Australian and other works in the festival’s program and, shortly after, the visual arts component. This week Mitchell and I focus on the major theatre and music components.

Until the Lions, Akram Khan Company, photo Jean Louis Fernandez courtesy OzAsia 2017

Akram Khan Company, Until the Lions

At first glance, British choreographer Akram Khan’s acclaimed Until the Lions, a dance adaptation of a story from the Mahabharata, seems an unlikely ‘personal’ tale. Mitchell explains, “It is a big work, with a big set, but it’s a particularly individual story. The creators, Khan and poet Karthika Nair, have focused on a story they convey from a female perspective about a princess, Amba, who is abducted by a general, Bheeshma, and she seeks venegeance.” Nair had gathered stories about often unacknowledged female characters from the Mahabharata in her book of poems Until the Lions, which became the title of her collaboration with Khan. In an unusual twist, Amba kills herself, is reborn and changes gender to defeat Bheeshma. Nair has explained the title: it’s based on an African saying about who gets to tell the story after the hunt — usually the hunter; but the tale is not properly told until the lions speak; as it should be for the women in the male-dominated Mahabharata.

Although British reviewers have praised the work for its adroit abstraction and use of symbolism, Mitchell says, “dance theatre is such a loose term, but Until the Lions is a narrative told through dance in 55 minutes. “As with a play, “you need to watch and decode to understand.” A YouTube trailer offers glimpses of an engaging blend of the literal and its abstraction, particularly in fight scenes.

Recalling Mother

Mitchell describes Recalling Mother as conversational performance but also as another very physically expressive work. Singaporeans Claire Wong and Noorlinah Mohamed are friends who explore their relationships with their non-English speaking Cantonese and Malay mothers, taking turns to play each other’s mother in mother-daughter dialogues. Mitchell tells me that when the work was first performed almost 12 years ago, the emphasis was on comedy and the language and culture-clash tensions “between tradition and Singapore’s slightly hybridised Western identity. The humour is still there, but the artists don’t remount the play so much as recreate it now that one of the mothers has dementia and the role of carer and a sense of mortality have entered and intensified the sentiment. The show runs for 75 minutes but with a Q&A which the artists see as part of it, because they feel audience members need to debrief about their own relationships with their mothers.”

In an interview, Noorlinah Mohamed said of Recalling Mother, “It is perhaps the first and only theatrical project, that when restaged, is always revisited as a new creation. The work is a living durational performance where life and art parallel and inform each other.”

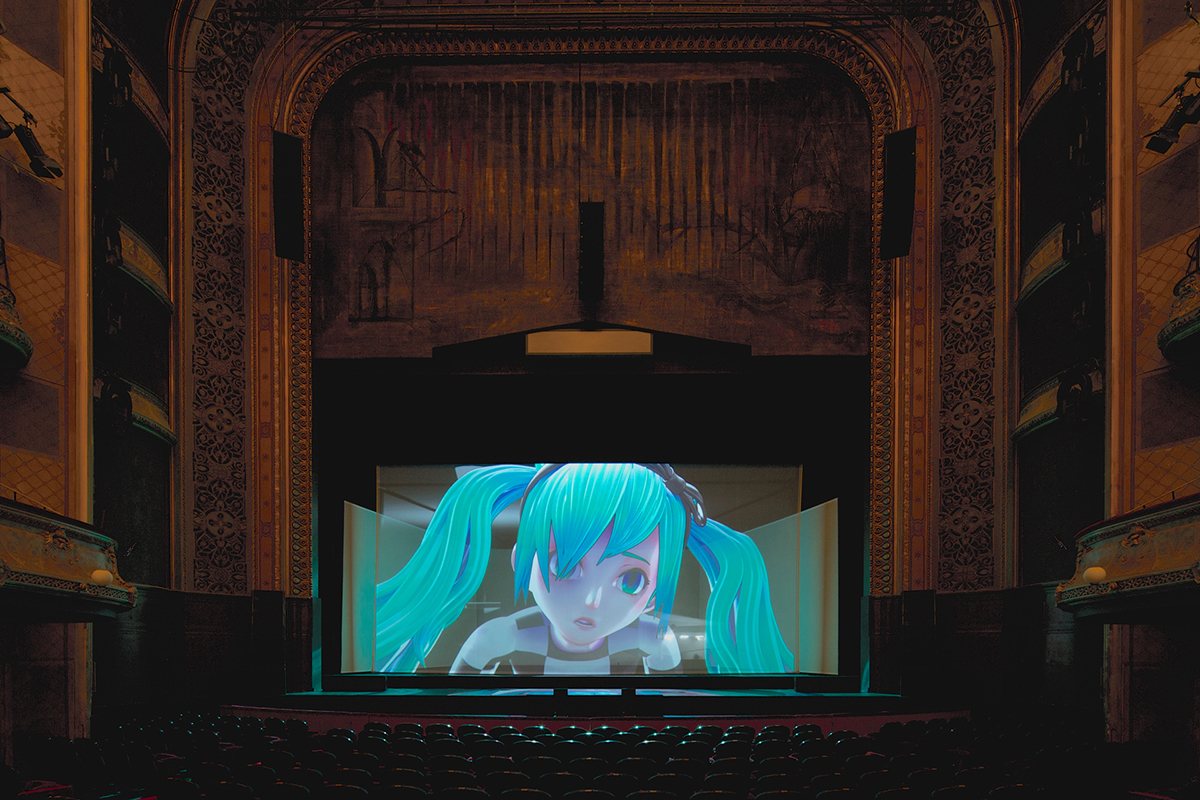

The End, Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, photo Kenshu Shintsubo courtesy OzAsia 2017

Keiichiro Shibuya + Hatsune Miku, Vocaloid Opera: The End

The sense of the personal might seem to evaporate when contemplating two works by a Japanese artist which feature non-human performers: one with a vocaloid (think singer + android) and a robot. Of Asian artists setting the agenda in performance, Mitchell sees Japan’s Keiichiro Shibuya, “with his bold sense of provocation,” as the standout exemplar. He has created The End, an opera for theatre without live singers or an orchestra for virtual pop idol Hatsune Miku. Mitchell says, “she is one of the biggest pop stars in the world. She has some 100,000 pop songs about teen love and relationship breakups, composed by professional teams but also by hardcore fans via purchased software. Shibuya had been a fan and when his wife, a leading fashion designer, died and he spiralled into depression, he latched onto thinking about the nature of death and how Miku will never die. He thought, ‘What if I go into her psyche and find out who this vocaloid is, loved by the world?’ So he asked the novelist, playwright and Artistic Director of chelfitsch, Toshiki Okada, to write the libretto and approached Louis Vuitton to design Miku’s outfits for a giant opera. It’s the most elaborate of her set-ups for an appearance and involves four screens and a mini-screen behind which Shibuya plays the music live.”

Mitchell notes that “When The End debuted Miku’s fans turned out: they were nervous, keen to support her doing opera, hoping she’d last the distance, but had faith in her and were very excited to see her dressed by Vuitton. It went to Europe last year, a bit outside her realm, but created a fusion of arts lovers and fans.” He does believe The End “has to be a dividing piece in terms of the operatic voice. However, the score and the libretto have all the hallmarks of great operatic tragedy and self-insight. At a time of the Australian Government review of opera, a decline in audience numbers and the large cost of the subsidy involved, we need to think about the artform and let it evolve; this work points a way.”

Skeleton, Ishiguro Lab, Osaka University, photo Justine Emard, courtesy OsAsia 2017

Australian Art Orchestra: Keiichiro Shibuya, Scary Beauty

Shibuya makes another appearance in OzAsia 2017 with Scary Beauty, again with a non-human performer — Skeleton, a singing robot with its own neural network — and, again, imagined as a large-scale work. But, says Mitchell, that would have taken years to develop, so the artist was commissioned to present a version of the work with the incisively adventurous Australian Art Orchestra, led by Peter Knight, as part of an afternoon of three discrete concerts featuring Shibuya, guzheng player Mindy Weng Wang and, in Seoul Meets Arnhem Land, Ecstatic Beauty, the pairing of Korean ‘street opera’ singer Bae Il Dong and Daniel Wilfred from the Wagilak clan in the Northern Territory.

Joseph Mitchell sees a widespread preoccupation with robots as workers and service providers as ignoring the rise of AI, which demands of us a better sense of what it is to be human; that, he thinks, can come through art and the challenges offered by works like Skeleton. This cluster of concerts should be a festival highlight, invoking living heritage and evoking possible futures.

Hotel, W!ld Rice, photo courtesy OzAsia 2017

W!LD RICE, Hotel

The personal is given an epic dimension in W!LD RICE’s Hotel, 100 years of Singapore’s history performed over five hours. Mitchell describes himself as a slow decision-maker, but within minutes of seeing Hotel he knew he had to program it: “We have to do this, no matter what. It’s one of the best theatre works I’ve seen in the last few years and has never had a bad review. You can see it all at once or in parts and is a bit like watching a Netflix series — there are 11 stories of some 20 minutes each, with characters and incidents overlapping, characters ageing across 40 to 50 years and told through the lives of ordinary people — from British colonialism to the Japanese occupation, independence and the explosion of today’s queer culture.” The hotel is unnamed, but it’s easy to guess it’s Raffles and all that it has symbolised. Mitchell feels that, like Australia’s widely played Secret River, Hotel is a story that needs to be told. Read more about Hotel, Mitchell’s first large scale work for OzAsia, here.

Niwa Gekidan Penino, The Dark Inn

Although enamoured of earlier works by Kuro Tanino and determined to program him in OzAsia, the auteur’s most recent work, The Dark Inn, proved to be Mitchell’s ideal choice. “The early work was really ‘out there.’ Kuro’s a trained psychiatrist who has worked with a lot of people who don’t see the world the way we do, so he created theatre from their viewpoint. The sets were crazy, with strange dimensions: there were penises across the stage. I saw The Dark Inn in Kyoto last year and agree with people who think this is Kuro’s masterpiece. It won the Kishida Prize for Drama.

“A dwarf father and his tall son are travelling puppeteers booked to play in a country bathhouse but arrive to find a disparate bunch of characters who are not expecting them. In the kind of revolving, multi-level set Kuro’s famous for, with a Japanese bath, steam, inquisitive characters and odd conversations, the play is more about inner states of mind than a straight narrative.” Mitchell adds, “After appearing in major US and European festivals, this is Kuro’s first visit to Australia and is a great opportunity for audiences and those attending the Australian Theatre Forum during OzAsia to see new directions offered by this kind of work.”

Darlane Litaay, Tian Rotteveel, Specific Places Need Specific Dances, photo courtesy Indonesian Dance Festival & OzAsia 2017

Specific Places Need Specific Dances

The collaborative dance work Specific Places Need Specific Dances foregrounds personal desire. Darlane Litaay from Papua New Guinea and Tian Rotteveel from Germany, investigate “waiting in different places, sharing culture and exchanging daily habits” (program). Each visits the other’s home country out of curiosity, says Mitchell, “Darlane to experience Berlin’s underground club and dance scene, Tian to see traditional male garb and in particular the penis horn. To Western eyes, these can appear sexual and as empowering the male figure. There are readings you can take from this work about exchange, sexuality, queer culture and male identity. For me, this is a work which sits at the cutting edge of contemporary dance.” Two more artists, in their Adelaide premieres, confirm Mitchell’s commitment to dance that draws on tradition and local cultures while venturing in new directions.

Aakash Odedra Company, Rising

Aakash Odedra will perform a self-choreographed contemporary Kathak piece and works made for him by Akram Khan, Russell Maliphant and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Maggi Philips wrote of the performance at the 2015 Perth Festival, “Odedra’s presence and collaboration with an impressive list of contemporary choreographers delivered a sense of celebration awakened in a performance which gathered strength from tradition and experimentation alike, yet was humble and projected humankind as simply strange and remarkable in a world of mystery, beauty and pain.”

Eisa Jocson, Macho Dancer

Eisa Jocson, who has appeared in Performance Space’s Liveworks in Sydney and Melbourne’s Asia TOPA, performs her eerie, gender-bending solo work Macho Dancer, drawn from her personal observations of Filipino club dancers. She said in an interview in RealTime, “Macho dancing is performed by young men for both male and female clients. It is an economically motivated language of seduction that employs notions of masculinity as body capital. The language is a display of the glorified and objectified male body as well as a performance of vulnerability and sensitivity.”

I wrote of this striking performance in 2015, “Jocson becomes a young, gum-chewing male dancer passing though a series of telling phases in which he is variously proud, defiant, calculatingly erotic and sulky; at one point he stops dancing and withdraws into upstage shadow — a tease or a moment of existential doubt?”

We’ll tell you more about Joseph Mitchell’s third OzAsia Festival in coming weeks, but already I feel a sense of eager anticipation building around the prospect of entering the idiosyncratic worlds of Akram Khan, Keiichiro Shibuya, Kuro Tonini, W!LD RICE and Darlane Litaay and Tian Rotteveel, with their offers of opportunities to redefine art and self.

–

OzAsia Festival, 2017, Adelaide, 21 Sept-8 Oct

Top image credit: The Dark Inn, Niwa Gekidan Penino, photo Shinsuke Sugino courtesy OzAsia 2017

Too often we take for granted the waterways that flow through our cities and towns. Artist Laura Wills’ public art project Creek Lore actively addresses this neglect by engaging participants in a guided walk along a short stretch of First Creek in Adelaide’s leafy eastern suburbs to explore its health, history and usage. First Creek is one of five creeks fed by Adelaide Hills rainwater. With around 25 other people, on a sunny Saturday afternoon, I participate in one of the hour-long walks.

Beginning at Marryatville High School through whose grounds First Creek runs, we stumble along the dry, rocky creek bed, duck under bridges, peer into the backyards of adjacent properties and hear several speakers discuss the creek’s environment, ownership and historical significance. There’s been little rain in May and the creek has not flowed for weeks, but last September, following a huge storm on top of a wet winter, creeks and rivers across the Adelaide plain flooded and First Creek was not spared the deluge.

The first speaker, environmental lawyer Dr Peter Burdon, outlines the Indigenous law that governed the use of the creek prior to colonisation and the British-style law that has governed it since. The creek is no longer owned as a single entity and managed as a resource, as it was by the Kaurna people of the Adelaide plain, but is now controlled by various local government bodies and private owners of the land through which it runs. Fragmented ownership and control limits effective management and allows degradation of the ecosystem. Burdon notes that there are moves to recognise the legal rights of waterways to allow them to regenerate, citing New Zealand’s Whanganui River and India’s Ganges River which have been granted legal personhood. The question is how effective legal recognition of Australian waterways might be in improving waterway management and in recognising the traditional owners of the land, and how such recognition might work in practice.

Audience, Creek Lore, photo Janine Peacock

The second speaker, Marryatville High art teacher Maeve O’Hara, tells of students’ engagement with the creek, the local environment and the heritage-listed trees in the area. There is a communal bark-collecting project, and students make artworks on the theme of the creek and its environment. Sensitising students to ecological awareness will hopefully produce a generation better inclined to environmental management than mine has been. The Creek Lore guides encourage us to collect rubbish as we walk, and despite a similar walk and associated rubbish collection having taken place a week earlier, there is still more to be retrieved.

Forager Kel Amity discusses local flora and displays a selection of edible and medicinal plants which can be found around the creek, including wild lettuce and rocket, nasturtium flowers and Moreton Bay figs. Further along the creek, Choral Grief, a community choir, give a performance, and we find ourselves in the backyard of Paula and Richard (surnames not provided), who describe changes to the creek over the 20 years they have lived there. They consider that the 2016 floods could have been mitigated by more frequent clearing of rubbish traps by local government and support the view that creek management should be reconsidered.

Further along, Laura Wills speaks of her childhood near the creek and its history and describes 19th century records of Kaurna camps along its banks. Wills has installed several evocative artworks along the creek bank, including Water, a digitised composite photo of the flooded creek printed on a large rectangle of cloth and suspended between two trees; baby birds assembled from cloth, knitted wool and gumnuts to draw attention to the loss of bird life; pieces of fabric embedded in the bank suggesting clothes and linen; and paintings on rocks lining the bank, depicting trees in the flooding rain and recalling Indigenous rock art. Participating artist William Cheeseman’s fish trap, a woven basket set into a rock barrier that funnels fish into it, shows how the original inhabitants sourced food.

Purple Spotted Gudgeon 2017, Collaborative work with Marryatville High School year 8 students

site-specific ephemeral work Creek Lore, photo Chris Reid

Our walk ends at the delightful Tusmore Park, with its barbecues, chlorinated wading pool and lush lawns amid ancient red gums. An old stone footbridge crosses the creek. There’s no trace of the 2016 flooding that inundated the park and filled the pool with mud. We’re directed to artist James Tylor’s simple installation — a metal plate fastened to a large rock in the creek bed stating, “do you know what happened here? you are standing on Kaurna country” — an unobtrusive but articulate reclamation of the site and its history. Tylor tells participants of Kaurna welcoming traditions and the process by which traditional culture and inhabitants were eradicated by colonists in the 19th century. Twenty-five years ago, I used to take my kids to this park but knew little of its history. At the walk’s conclusion, tea and cakes are served and artists, speakers, volunteer helpers and participants mingle.

Laura Wills’ account of her relationship to the creek is a very personal one, as are those of James Tylor, who is of Kaurna as well as Maori and European descent, and Paula and Richard. There is a Creek Lore blog to which people have contributed. These personal accounts prompt us to think of our own connections to place, and this seems the real point of the relational Creek Lore project — to encourage us to reconnect to place and to neighbours. Wills worked with Open Space Community Arts (OSCA) to develop Creek Lore, which is subtitled a “project of the everyday,” one of a series of OSCA projects intended to encourage community engagement.

First Creek is no longer an essential food and water source but a storm-water drain that sometimes clogs up. Community engagement has the potential to recognise the creek as an ecosystem and acknowledge traditional and current proprietors and users. Now that I’m more aware of the history of the area, I feel a greater sense of connection and responsibility. Practical steps beyond this project are unclear, but community engagement and activism at the local level can establish an important foundation in addressing broader social and environmental issues.

–

Laura Wills and OSCA, Creek Lore, Marryatville, Adelaide, 13 & 20 May 2017

Top image credit: Embed, 2017, site-specific ephemeral work, Laura Wills, Creek Lore, photo Juha Vanhakartano – Valo Productions

Half an hour’s drive northwest of Adelaide’s CBD, flanked by the Birkenhead Bridge on one side and the recently refurbished Hart’s Mill precinct on the other, is the heritage-listed Waterside Workers Hall in Port Adelaide. Since 1984 the Hall has been home to the contemporary arts organisation Vitalstatistix and its expansive, markedly queer and feminist programs of interdisciplinary performances and developments. It’s often joked, sadly not without foundation, that Port Adelaide is too far for metropolitan-minded Adelaideans to travel. It’s also true that the weather can be bitter as the area’s many alleyways channel the icy Port River winds, especially during the middle months of the year.

And yet Vitals, as it’s usually referred to by locals, is a unique place, neither regional nor exactly urban, a site both for intensely private experimentation and the generous laying bare of artistic process. All the while it feels socially embedded, part of the fabric of the community, in a way that few arts organisations do. When I think of the company I picture happily shivering through the three public days of its annual national hothouse Adhocracy, traditionally held over the June long weekend but lately shifted to early September. In a way, the image seems resonant in its stoicism; Vitals was defunded in the 2014–15 Federal Budgets, determinedly reshaping its 2017 program around an interim, one-year funding agreement struck with the State Government. Perhaps, too, there is something fitting in Adhocracy’s move to the first weekend of Spring, traditionally a time of rebirth and renewal.

In what are lean times for independent artists, Vitalstatistix continues to heavily invest in individual practice — not a funding priority in the 2014–15 Federal Budgets — on both project- and career-focused bases. Its program this year is a rich one: an expanded residency series, six new commissions through the Climate Century project and, in addition to Adhocracy, now in its eighth year, a multiplicity of exhibitions and work-in-progress showings through partnerships with around half a dozen organisations including the Tarnanthi Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art, which will co-present Brad Harkin’s exhibition of visual art and sound work, LOSS. GAIN. REVERB. DELAY. at Waterside in October and November.

Waterside Workers Federation Hall, home of Vitalstatistix

In the aftermath

I began by asking Webb how the loss of operational Australia Council funding — also the fate of four other South Australian arts organisations, Brink, Slingsby, the Contemporary Arts Centre of South Australia (CACSA) and the Australian Experimental Arts Foundation (AEAF), totalling $1.8 million in cuts — affected this year’s program. “The impact of the cut was twofold,” Webb says. “Obviously it had an immediate financial impact but it also has a long-term effect — just as impactful in some ways — around stability and planning and not knowing what resources are ahead. The interim funding agreement enabled us to have a full program this year and we had to think about how best to use those extra resources. And so the combination of that opportunity and the funding cuts, and that question of being able to plan forward, led us to decide that the best use of our resources in all of that context was to seed a whole lot of new projects and development. By the time we select the Adhocracy projects” — this year there will be between seven and nine, plus the residency project Second Hand Emotions — “and finalise the Climate Century program we’re looking at close to 30 projects under development, many of which we hope to present in our programs in future years.”

The art itself

She continues: “Our work has always been artist-focused but this year particularly so while still having substantial public engagement through all the different showings and labs and public talks. When you’re not spending your money on box office risk or all of the marketing you need to do when you’re presenting ticketed shows, you’re able to really just focus on the art itself. We’ve been saying it’s kind of like Adhocracy but expanded throughout the year, and we feel like that’s a unique offer that we’ve been making artists and audiences for some time — to come into the process of experimentation and see how art is made while at the same time artists are receiving feedback from peers as well as the general public.

“This year’s program feels a little bit ‘Festival of Ideas’ as well, because all of these projects we’re commissioning and presenting as works in progress are engaging with a whole lot of important themes and ideas and conversations. So we’re thinking about it as a public dialogue.” One vivid illustration of this is Climate Century, a five-year project begun in 2014 that invites artists to respond to the question of how we, and future generations, will come to understand the climate change tipping points we are currently living through. In development this year, in 2018 the project will culminate in the presentation of six commissioned works, including one regional work produced in partnership with Country Arts SA.

In the Incubator

This year, Vitals’ long-running program of two-week residencies, called Incubator, has been expanded from two projects to three, while a second stream has been added that will see two groups of artists in residence throughout the year. In May there were work-in-progress showings of regional SA theatre-maker and writer Rebecca Meston’s Drive, an intriguing choreographic response (with Adelaide choreographer Larissa McGowan) to a 2007 true crime case in which a female NASA astronaut attacked her partner’s younger lover. In residency this month are Melbourne performance makers Nicola Gunn and Tamara Saulwick who are developing Super Imposition, a fusion of performance, music composition, and video art that is also being supported by Melbourne’s Chamber Made Opera. Finally, in July, musician and composer Cat Hope (ex-Perth and now Melbourne-based) will present showings of an experimental opera, Speechless, produced by Perth’s Tura New Music and inspired by Gillian Triggs’ 2014 Human Rights Commission report on children in immigration detention.

Two additional year-long residencies present a different model of development, one that is not simply about making work. One will see “conversationalist” Emma Beech (SA) installed in the Shopfront Studio at the Waterside Hall where, as well as rethinking her own practice as a theatre-maker, she will act as a sort of ambassador for Vitalstatistix by engaging directly with the Port Adelaide community. The other, called Points in the Plane, will provide three emerging local multidisciplinary artists, Josie Ware, Ashton Malcolm and Meg Wilson, with a mentorship facilitated by Webb that will explore the nature of their collaboration, which began at Adhocracy in 2014.

Emma Webb, Climate Century 2015, photo Tony Kearney

A choice selection

And what criteria, I ask Webb, are employed by Vitals to select the artists the company chooses to work with? “One of the things that we try to do,” Webb explains, “is to work with both emerging and mid-career or established artists. We certainly work more with artists who are well into their career — I don’t feel we’re an emerging artist organisation per se — however, a good example is Adhocracy, where we always try to make sure we select projects by emerging as well as established artists because we find that combination is great for the dynamic kinds of conversations and processes that happen there. I would also say we are certainly interested in projects that have an engagement with the world and with I guess what you could say are progressive ideas. We’ve been doing a lot of work recently around climate change, and historically there’s a feminist and queer eye across a lot of how we think about the organisation and its programming. In the last little while we’ve also supported a lot of work that is to do with economics: the economics of art-making, ideas of resilience, the economic crisis, and so on.”

“We’ve also in recent years,” Webb tells me, “had quite a lot of engagement with dance, which is interesting because we’re not a dance organisation but have just found those kind of expanded dance practices to be really interesting at the moment. I love dance so I think that’s something that’s been noticeable about our program in the last couple of years. The other thing we look for is what the collaborative process within a group is like, who’s proposing to work with who, and why. Take, for instance, Nicola Gunn and Tamara Saulwick’s Incubator residency. We’ve worked with Nicola a lot and I’m a big fan of both those women’s work and this is their first collaborative project, which is exciting for us apart from anything else. So we definitely look for artists who are proposing something new.”

The cash

Webb elaborates: “All of our opportunities come with a cash contribution and artist fees attached as well as quite significant in-kind support, whether it’s through the physical residency at Vitals or working with our staff. I try to spend lots of time with the artists. Also small organisations like Vitals can offer a different kind of place to make work that puts you in a unique context and environment and politic. We feel like artists really appreciate the time and space they get in Port Adelaide and at Waterside. I think also one of the things we’re adept at is finding partnerships — I think pretty much anything we’re doing at the moment is in partnership with other organisations. It’s a really great way to maximise resources and give artists the biggest kinds of opportunities and platforms possible.”

Jo Lloyd, Speech Pattern, co-creator and photo Davis Rosetzky

At work with PADA

One key partnership is with PADA (Performance & Art Development Agency), founded by Webb and Steve Mayhew in 2015 as, in Webb’s words, “a small, city-based, project-based, curatorial project.” It grew out of discussions between the two around curatorial diversity in South Australia, and whether the time was right for a new contemporary arts organisation. They decided it was, and then everything changed — Brandis, the 2015 budget, and all the rest. In 2015 PADA presented its first public project, the exhibition Near and Far [read the RealTime review], at the Queen’s Theatre in Adelaide. “In 2014,” Webb explains, “there was nationally much more a feeling of confidence in the sense that there was going to be an opening up of opportunities, potentially through the Australia Council, but obviously all of that changed. We decided that for this year we would umbrella the projects we had commissioned during the cuts under our respective organisations, Vitals and, in Steve’s case, Country Arts SA. It seemed the smartest way to deal with resources and time if we were going to make sure those artists were able to be supported and carry their works through to the next stage of development.”

Work-in-progress showings of two of these works — Larissa McGowan’s Cher and Melbourne media artist David Rosetzky and choreographer Jo Lloyd’s Speech Pattern — were featured last month in Physical Forces, a program of dance works presented by PADA, Vitals and ACE Open, the new contemporary arts organisation merged from the remains of CACSA and the AEAF. Also under co-development with Vitals and PADA are Rebecca Conroy’s Iron Lady (NSW) and two works by artists with extensive experience in Europe, Daniel Jenatsch’s Enheduanna and Adelaide-born Chris Scherer’s Duncan. The latter was presented as part of the Art Gallery of South Australia’s Versus Rodin exhibition in April. Reflecting on the collaboration, Webb says, “Curator of Contemporary Art Leigh Robb was incredibly generous with Chris, and it’s started conversations between us around what performance art in a gallery looks like.”

Solidarity

Thinking about these kinds of work and Port Adelaide, with its post-industrial, gentrifying but for the moment still ragged air, does suddenly seem distant, half a world away from the Art Gallery’s crisp white walls. And yet it strikes me too that one of the few good things to have come out of the funding crisis has been a refreshed sense of industry solidarity, of people and organisations reaching out across artistic divides — perhaps not as wide as we had first thought — in ways that have not, or only fitfully, happened before. Just before I sat down with Webb I noted that a work developed at Adhocracy in 2015, Applespiel’s Jarrod Duffy is Not Dead (NSW), had gone on to a full presentation [read the RealTime review] at Brisbane’s Metro Arts in April. It must be pleasing, I suggest to Webb, when such projects bear fruit. “It’s incredibly satisfying,” she says, “to see these seeds blowing into all kinds of places.”

–

Vitalstatistix: Incubator residency work-in-progress showings, Nicola Gunn and Tamara Saulwick, Super Imposition, Waterside, Port Adelaide, 30 June-1 July; Cat Hope, Speechless, Waterside, Port Adelaide, 28-29 July; Adhocracy, Waterside, Port Adelaide, 1-3 Sept; Vitalstatistix and PADA, Daniel Jenatsch, Enheduanna, Nexus Arts, Adelaide, 27-28 Oct; Rebecca Conroy, Iron Lady, venue TBC, 13-26 Nov; Vitalstatistix and Tarnanthi, Brad Harkin, LOSS. GAIN. REVERB. DELAY., Waterside, Port Adelaide, 18 Oct-5 Nov

Top image credit: Josephine Were, Meg Wilson, Ashton Malcolm, Points in the Plane, photo courtesy the artists and Vitalstatistix