Something more than choreography

Company in Space’s Hellen Sky at the RealTime/Performance Space

Flesh & Screen forum

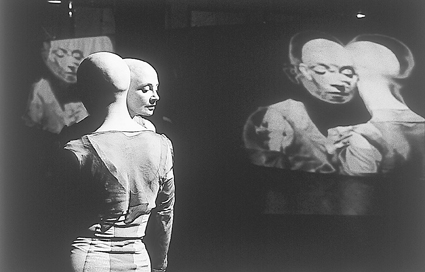

Company in Space, Escape Velocity

Across Australia, there are a significant number of artists and companies working with digital media and in multimedia, each in their own distinctive way, sometimes continuously, occasionally in one-off projects, exploring the relationship between live and pre-recorded performance, or between live and realtime mediated performance, or combinations. This list is by no means exhaustive, but it is indicative of the extent of the engagement: Arena Theatre, Trash Vaudeville, Bonemap, Back to Back Theatre, Sidetrack Performance Group, Urban Theatre Projects, Melbourne Workers Theatre, Nerve Shell, Salamanca Theatre, Dance Works, Heliograph, Doppio Parallello, Anna Sabiel and Sarah Waterson, Dina Panozzo, Marrugeku Company, Louise Taube, Snafu, skadada, Sam James, Mark Rogers, Brink Visual Theatre (Brisbane) and Cazerine Barry. The most dedicated and widely travelled (and broadcast) of groups committed to exploring performance and technology, and for the longest time, has been Company in Space.

In the first of the RealTime/Performance Space forums for artists about vision, training and practice, Company in Space co-Artistic Director Hellen Sky talked to Keith Gallasch, with questions coming from the audience when they wished. This is a small part of a much longer discussion available on the RealTime website. After a brief introduction to the work of Company in Space (John McCormick is co-Artistic Director ), Keith asked about the dancer’s “relationship with the screen in performance, your awareness of the other dancer who is in another space?”

It’s not like you’re watching the screen all the time but a part of your eye, if you need it to, is going to the screen. In telematic works when you’re dealing with different geographies, the screen is your conduit to the other dancer. No longer are you sharing a space, no longer can you hear their breath, their footfall. When working in any group choreography and looking at simultaneity of movement, your perception is already in the physical space, not just through your eyes, it’s listening, you feel the people you’re dancing with. There is this shared body thing. When you separate from that, you still have to feel that you’re sharing that space, that you can get this sense of them being there. In terms of consciousness, this is very expansive—how might you perceive yourself being in the moment of the performance? But there is this thing which is the screen. And it changes depending on the circumstances. In January I was in Hong Kong and Louise Taube was in a nightclub in Melbourne. You can’t always put the screen exactly where you want it to be in the performance space. It’s not like you can always design it to have the privilege of your point of view going straight to your partner. And you don’t want to be looking at the screen anyway. You actually want to be addressing all the other things that are going on in the space.

KG Here on video are 2 versions of Escape Velocity, one Hellen calls the “contained” performance, and then the telematic version performed in 2 locations.

This was done in 1998 in a non-conventional space. At this point, the hand and the head are orchestrating the sound. So very small movements of the body are creating the score. What you can’t see is the little laser lights on the floor, a grid that doesn’t emerge in the video. The movement is being motion-detected. The velocity of the movement is creating the score. The other sound is being mixed into the score because there’s a ledge up there and we were out of the range of the camera and couldn’t trigger the score. We’re about 6 metres up in the air by now. You can see Kelly and Luke here. They’re the ones down below who are stopping us from falling on our faces. Not only are they belaying us through all of this (controlling the raising and lowering of the performers) but they’re also filming us from underneath and our images are being fed into the computer and an effect added and it’s going across a whole cyclorama of screens at the back. This is their camera point of view happening in real time as they’re belaying us and leaning backwards on the floor. The whole thing was about gravity and loss of gravity. Where is the body really when we have the possibility to exist in this virtual space where there’s no gravity? What is meaning there? What is memory there?

Audience All the movement is set?

It’s set in that if we want it to go slow we can. In that section where we’re pushing it, we still have the privilege of being with each other and hearing each other. The movement is trying very much to be in unison. If we were to hang back we would do so together and know that we’d brought the score to silence. So from night to night, there’s some flexibility to deal with—’Hey, I really like it here. It’s good to have it quiet for a bit.’ It’s quite flexible.

Audience The audience is not necessarily aware what is happening technically?

In a way I don’t care if the audience knows it or not but it changes my relationship to it and, therefore, it changes my presence and the evolution of the piece.

Audience I can see that not knowing that the dance and the sound are connected wouldn’t matter but the sound seems like a sea of sound. How does the technology handle specific or subtle movements affecting the sound?

When we were experimenting with it, I could go like that with my little finger and Garth Paine could make it a huge or a little sound or it could happen 4 minutes later. That’s its potential. That’s a nice thing to play with. I could put the camera on my face and just do a whole thing with my tongue. It’s something more than choreography responding to music. It’s an expansive experience. And, if we had the privilege of being able to educate ourselves with this stuff, it’d be an expansive experience for the body to learn.

Audience Those little movements, do they happen live or did they have to be pre-programmed?

Absolutely in real time. I could ask him to delay the data and it would be different. The collaboration then is what becomes of data. I have to know the possibilities. Those are the things that take time to negotiate. For Garth to be able to set up the parameters and the data it takes time but it’s quite interesting. These animations and graphics are pre-constructed with a brief. Some of them I made and some of them I’ve worked with an animation artist. I don’t work with 3D graphics. You can’t do everything. That’s great. Why would you want to? Other people do one thing really well. You don’t have to multi-skill. When you’re beginning maybe you want to just so you know. I worked with an electronics engineer and each of the laser lights had stepper motors on them so that when you broke the laser beam the light would shift. My idea was to have a 3- dimensional light space which enclosed the body but which kept shifting around it. Sometimes these things fail too. The stepper motors didn’t always work but there’s a sense that I’m changing the light around the body.

Now you can see the 2 dancers juxtaposed against this but then the camera choreography comes in and we’re working with a duplication of ourselves in the video frame. Now Louise is in red and has an overhead camera with virtual objects in it. Her virtual body is breaking these objects, creating noises, constructing her score. You can see the little icons there on the field. So we have an overhead camera point of view which is giving her virtual body the option of being able to break a virtual video object which can change the background but also orchestrate the sound in real time.

Audience What’s a virtual video object?

It’s a video icon which you can call a button. That’s one layer. The mixing in of the camera point of view is another layer. Then the animations under that are another layer. When this object perceives the breaking of the object from the virtual camera body, it triggers the sound. That’s the system that John invented.

KG That’s the video of the “contained” version. Here’s the telematic duet.

This was between Arizona and Melbourne. And just to think about how you might set something like this up is a whole dialogue in itself. It’s about pragmatic things, about finding overseas partners who understand what you’re trying to do…and installing the link. Just getting the link right! That’s me in Arizona chatting to the audience. It was a thing called International Dance and Technology that they held at Arizona State University (see RealTime 31, page 35). The other place is the Rusden Campus of Deakin University.

Audience How is it connected?

Through an ISDN. A single line. 264k ISDN so it’s 128k point to point ISDN. ISDN is what they use for tele-conferencing in the corporate sector or in the medical and educational sectors more and more, when you have 2 or 3 talking heads.

Audience It’s like 6 telephone lines.

And ideally you want to have 3 of them. But each time you do it between here and America it’s like a $450 per half hour phone bill. So, the thing about budgets is interesting once you start working on it. So for me to do this work was to reduce it from about 45 minutes into a 20 minute performance where the 2 camera operators and 2 dancers are in separate locations. The negotiation of framing is very intuitive. They’re having to watch the screen output and know that they’re putting us in the right relationship. Also, the intelligent hub with all the computers and the camera network is based in Melbourne and it’s a camera feed that’s going through to Melbourne. On the way it’s going through a whole lot of processes and it’s being sent back and there’s a 3 second delay. So there’s this whole thing about time. Some people might see it as a problem. I think it’s quite interesting that time is altered because you’re trying to pipe all this visual and audio information through what can be a 2 way exchange. You can see here that the image is slightly degraded, my image moreso than Louise’s. I like that. Something’s happening in the conduit. I think that’s interesting.

Audience I’m curious at what point, if ever, do considerations of more traditional screen arts and their processes and methods come into play?

A lot actually and maybe in our next work it’s more obvious. Often when you’re having to control the cross-fades between 4 or 5 cameras it’s much more cinematic and cinematic in real time. Things like the duration of a cross-over, when you want that to happen. It’s very much a part of the direction of the whole work. As a choreographer I always used to work with film. I’ve been a photographer and a lot of my work would have Super8 or slides or something to do with light. I guess when we first started to work with these computers, there was a way of actually having all these different things speak to each other through a hub which meant there was a duplicity of possible juxtapositions of meaning, and that keeps happening now but through more complex interfaces.

Audience Does it influence considerations of structure in the whole work?

It does. Is the image just happening on the screen? Is it happening in the space? How long will the image be suspended? I don’t know if we’re consciously thinking about filmic structures in terms of say scripting but we’ve discovered that we score things in quite a complex way. When you’re thinking about which camera, what frame, what effect, what cross-over, I suppose we are. But I hadn’t deliberately thought about working in the sense of say, story-boarding or something like that.

KG Trial by Video is interesting in terms of site. It was done at the Economiser Building and in the Old Magistrates Court in Melbourne where Ned Kelly was tried. It’s been done in an old building in Glasgow recently. What’s the importance of site in the work you perform?

I think they empower a work. I suppose that’s my visual arts perspective—how you install a work, what you actually get from the physical space, how that can amplify the content, how can you construct things so that they’re satisfying for people just to walk in as an installation before they become enlivened through the performance. There’s lots of histories and textures, possibilities within the physical space we’ve worked in.

For Trial by Video we set up installations at PICA in Perth and at Performance Space and another space in Brisbane. Simultaneously, we were performing in an underground railway station in Melbourne. We had 2 cameras set up in the installation spaces with 2 cameras and an ISDN connection so that the viewers at this end could do certain actions and have an influence on the performance as it happened in Melbourne. They also became part of the visual environment of the performance work.

The tunnel was blocked at both ends so people were contained within the 2 screens at either end of the tunnel. In each of the spaces in PICA and Performance Space and here we had the screen, the cameras, a tray of sand (audiences could move the sand to trigger sound) and a giant book with black and white pages. We did it in 1997 when Pauline Hanson was so, um, “outspoken”. It’s a very political work deliberately looking at the technology and the power of the media to be able to manipulate the masses and what the potential offloading of that is on an individual.

KG A lot of it is about the language of political gesture.

All of the movement was done from John’s research into gestures. Basically a person doesn’t just have identity through language and appearance but the way they talk with their hands is a development of who they are. He gave us scores of gestures to use. I was the voice of dissent. He was a politician. It’s a very strong work and even though it was done in 1998, no matter what context we do it in again, (we did it in Glasgow in March this year) the work becomes more sophisticated because we know more about the technology and possibilities. We change it according to the political environment. If you’re actually looking at media power and politics, it’s not ever gonna get out of history. You’ll remember there was a strong anti-Asian immigration debate going on too. John’s half-Chinese and he learned the gestures from A-Z of all of these different words and performed it like a language test. It was as if he was being tested in Chinese and English. There was also a little bit of text from a Pauline Hanson speech—another flavour to the oral content.

KG What have you seen of motion capture technology?

Merce Cunningham has done some great things with motion capture. I saw it at SIGGRAPH in 1998 in Florida. He has 3 screens and he’s working with coming in and out of the frame. And it’s Merce’s choreography. You just know it’s Merce’s choreography but it’s not a body. It’s just this whisp of a line but it has weight because it’s come from a body with weight. And it’s beautiful, it’s just beautiful. And I’m thinking I’m getting old too and perhaps I can keep going on too. That’s a big thing about age and Australia. A lot of us want to keep on moving and there’s not a lot of acceptance for older movers in this culture.

Audience I think technology has the potential to change what we experience as a real event. That’s really going to change a lot in the next 20 years if they do away with the screen and write on the retina. So your experience will be like a waking dream. There’s still touch and smell locking you back down to earth but…

At SIGGRAPH there was a wonderful woman called Gretchen from Paris. She’s an installation artist working with ‘a trip around the world.’ It was much more lateral than that but the way you experienced it was on a little footpad that had pebbles. Depending on how you shifted your weight, you went on a journey. The materials were all very tactile but it was like this very haptic relationship to the technology that just grounded the body in this other experience. It was so beautiful. That’s installation work but the thing of touch and so on are important to work about the interfaces—not just the eye and the body and the screen.

KG That’s something that Mari Velonaki’s doing in her work.

Mari Velonaki Yes, I’m trying to link the spectator with a projected digital person through objects, through smell, touch, breath…

In installation it’s very much more a one-to-one relationship. Even though you might be in a room with lots of people and there might be devices that are making that more complex, the notion of engaging in the experience in an installation is still very much yourself with it. When it can be as haptic as possible that’s when it’s most satisfying.

Mari Velonaki When you can forget about the interface and just go through it.

Company in Space’s new work Architecture of Biography (see Working the Screen 99, page 16) will premiere in association with Melbourne International Festival 2001.

RealTime issue #38 Aug-Sept 2000 pg. 16-