Singing the sound of the world

Keith Gallasch: interview, Bill Burns, Junction Arts Festival

Bill Burns

photo Krys Verrall

Bill Burns

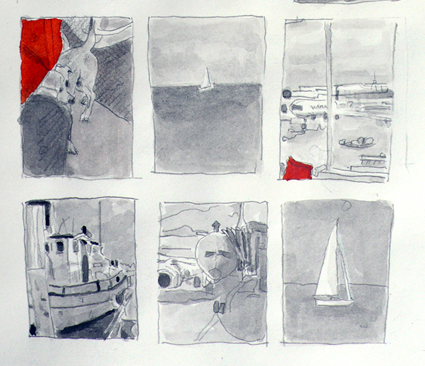

Seriously idiosyncratic Canadian artist Bill Burns is a featured guest of Launceston’s 2013 Junction Festival. His art has humour, bite and an intriguing diversity of means that focus on our relationships with nature, politics and the art market. His work has been shown at London’s ICA and New York’s MoMA and his nine books include Dogs and Boats and Airplanes told in the form of Ivan the Terrible (a photo-montage version of Eisenstein’s film featuring only dogs, boats and aeroplanes).

Although famed for being, as one writer put it, “a fabricator of small worlds that contain big ideas,” like his Safety Gear for Small Animals (1993-…) which comprises small hard hats, safety vests and respirators for all manner of beasts, Burns is creating a very large, live work for Junction.

Dogs and Boats and Airplanes Children’s Choir is a collaborative artwork performed by a 100-strong children’s choir sourced from four Launceston schools. The children, aged 8-12 years, will chorally mimic the sound of dogs, boats and aeroplanes in a libretto of their own making. Fifty other children will create the set, props and lighting for the live theatre performance which includes the making of pageant floats. I spoke with Bill Burns by phone not long after he’d visited his first school in Launceston.

You’ve produced this work before but the scale of it this time looks amazing. You’ll be marshalling many forces—a corralling of cats.

That’s true. In a lot of ways it’s a premiere because I’ve never done a live version. We’ve done some recorded versions with children in a studio but never with 100 children and never live.

Are you working on your own or do you have a team?

There’s quite a big team. First of all, it wouldn’t be possible without the support and expertise of the Junction Festival team. Then there’s a choral director, Amanda Hodder, from Tasmania—quite a well-known musician and choral director in this area. The artist Krys Verrall is travelling with me to work on the pageantry for the project, which takes place in between the choral movements. All of it is a very collaborative process with the children basically writing the libretto and developing the pageant.

I was working yesterday for the first time at one of the schools and it was pretty exciting. The kids are pretty pumped-up about it. The only thing to do now is to wrangle them into shape.

Dogs and Boats and Airplanes, Bill Burns

You’ve done works with children talking about birds and using mechanical bird sound devices (Bird Songs for Toronto, 2008), but why children making non-verbal simulations of the world around them?

I think that all of us can be artists, so I wanted to find a way that kids could be artists without having to go through all the hoops of acquiring certain kinds of technical expertise. And my work has a lot to do with expanding who can be creative in society. So for instance, I think all of us can be artists and that’s the way I would like my society to be—a place where everyone is an artist. But we have that drilled out of us.

Why specifically dogs, boats and aeroplanes?

I’m very interested in dogs and I feel like the connection between humans and dogs is really important to cultural history as well as natural history. So it’s this kind of relationship that borders quite nicely between nature and culture. And then, a lot of my works in the past have been about the tension between nature and advanced industrialism. So the idea of using the sounds of dogs and the sounds of boats and aeroplanes seemed like a way to bridge those tensions and look at them. And also being artists in the 21st century, we tend to travel a lot and I see a lot of boats and airplanes, but I also see a lot of dogs in different cities. So I’ve come to know dogs in Asia and South-America and the Caribbean and throughout Europe and the Americas. And I know that a dog in Paris and a dog in Seoul have different characteristics and they socialise differently. So you have this curious relationship between us and the dogs. And, of course, the dogs have this long history of working with humans as our worker dogs and protecting our sheep and so on. And those are very connected to human history. You know, dogs came out of Central Africa as well. So they come from the same place we do and we have a very long history with them.

I guess there’s a certain kind of sonic appeal for children in making a sound work.

Sometimes you forget the most obvious things and that’s one of them. It certainly appeals to the children. The boys gravitate towards the F18s sometimes but everyone is a pretty good howler and barker. Curiously, the boats tend to be more difficult. I think maybe they’re a little bit less known in our sonic culture.

There’s diversity in your art making, from watercolours to survival suits for small animals and your Guantanamo kit (Boiler Suits for Primates, 2009, a 1:5 scale model of everything that prisoners received when they arrived at Camp X-Ray in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba). How do you see them all fitting together?

Partly in that relationship between nature and the way things are going with advanced industrialism. A lot of my work has to do with that tension. One part of my work I’m looking at now is the relationship that artists have with the sort of industry of art. I think the Wall Street Journal recently was quoted as saying that art is becoming the fastest growing industry in the world. If you look at the auction results of the last four or five years it’s true; there’s nothing out there that has this kind of exponential growth. But, of course, the relationships are kind of strange and somewhat corrupted. I’m not to say they that anyone in particular is corrupt but there’s a kind of perverse relationship inherent in the fact that a contemporary artist like Peter Doig or Gerhardt Richter sells paintings at a higher price than Rembrandt—things like that. Not to say they’re not really interesting artists themselves, of course. But if you look at the stock market it’s not surprising that there would be a kind of a rush to this kind of possibility of inflated values for certain kinds of objects.

So a lot of my current body of work is looking at this kind of conspicuous consumption concept and the idea of what they call Veblen goods. Veblen was a Scandinavian economist at the turn of the 20th century who actually coined the term “conspicuous consumption.” The idea is that certain kinds of objects accrue value by virtue of their price tag. [It’s] a kind of reversal of Jeffersonian economics, the law of supply and demand. This is a case where the bigger the price tag the bigger the demand. You see that with fine wines, jewels, with watches, whiskey and with art. Those are the kind of curiosities I’m looking at. For me it’s a way of looking at the way we live in our society

You’re providing a counterpoint to excess by re-directing our attention as you’re doing in Dogs and Boats and Airplanes Children’s Choir?

Yes. At the same time I like to encourage younger artists because a lot of people are wont to say that art is a difficult field and there’s no money in it. And that’s far from true. While it is a difficult field, there’s a lot of money in it. It’s just that like everywhere else it’s concentrated.

Junction Arts Festival 2013, Bill Burns and Big Pond Small Fish, Dogs and Boats and Airplanes Children’s Choir, The Princess Theatre, Launceston, 6 September; http://junctionartsfestival.com.au; http://billburnsprojects.com/

RealTime issue #116 Aug-Sept 2013 pg. 29