screening the ‘other’ deutschland

hamish ford: gdr films, 2009 festival of german films

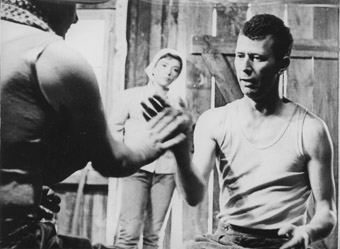

Spur der Steine/Traces of Stone

photo Günter Marczinkowsky

Spur der Steine/Traces of Stone

THE FESTIVAL OF GERMAN FILMS THIS YEAR BENEFITED GREATLY FROM THE PRESENCE OF SIX FILMS FROM THE ‘OTHER’ GERMANY: THE DEUTSCHE DEMOKRATISCHE REPUBLIK (DDR), THE GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC (GDR), OR ‘EAST GERMANY.’

Nestled alongside present-day productions at the festival set in the GDR or pertaining to its legacy—12 heißt: Ich liebe dich/12 Means: I Love You (Connie Walther, 2007) and Novemberkind/November Child (Christian Schwochow, 2008), both of which concentrate on familiar Stasi/police-state stories. Seeing films actually from the GDR puts contemporary treatments into some relief as (with exceptions such as Christian Petzold’s Yella, which screened at 2007’s festival) rather superficial and, perhaps surprisingly after all these years, ideologically determined.

Although Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary are considered to have produced more internationally recognised Eastern bloc filmmakers than the GDR, throughout its short existence from 1949 to 1990 its film industry was (as the festival program somewhat condescendingly states) ‘surprisingly’ productive and diverse. The films presented here concentrate on the work of three well-known and respected GDR directors: Frank Beyer, Heiner Carow and Konrad Wolf, none of whom can be considered straight propaganda artists (while being, to different degrees through the years, committed to their new state and its proclaimed socialist ideals even as they inevitably had problems along the way).

Perhaps the most ‘typical’ of these films in terms of socialist folk-heroism is Frank Beyer’s Karbit und Sauerampfer/Carbide and Sorel (1963), which tells the light-hearted story of a manly worker—though given idiosyncratic characterisation as a vegetarian non-smoker—after the war in 1945, who has to transport carbide from Wittenberge to Dresden so he and his comrades can restart a tobacco factory. Through the very accessible form of a comedic road trip (riffing on the chaos of post-war Germany but also, in one scene, a gullible US soldier), the film surveys the GDR at its ‘pre-’stage from a secure (newly Walled-in) future, as we watch Germany’s fragmentation at the hands of new Cold War geopolitics. Almost inadvertently, near the film’s end we glean that our earthy protagonist is a communist—communism therefore coming from ‘the people’ as opposed to being forced on them. This seems to perpetrate the silence that continues today around Hitler’s least discussed victims (which one might naively hope a communist cinema would eulogise), home-grown German communists. Secondly it elides the fact that those who did survive 12 years of Nazism were largely overrun in terms of political power by Soviet officials after the war. Demonstrating well the ‘folk art’ feel-good parable form to which much mainstream communist cinema aspires, Carbide and Sorel‘s historically problematic elements—echoing across the film’s setting (and horrific prior events), the time of its production, and from today’s perspective—make it all the more informative.

Still uplifting in its way but naturally grimmer in tone was Beyer’s and the GDR’s most internationally celebrated film, Jakob der Lügner/ Jacob the Liar (1974), winning a Silver Bear at the 1975 Berlinale (seen as a significant trans-Wall accolade) and nominated for a 1976 Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. Set in the Jewish ghetto in 1944, supposedly one of the first East German films to tackle the ‘Jewish issue’, this story concerns a cranky man who weaves a web of lies about the Red Army’s proximity (after inadvertently overhearing news through a Gestapo office door) and claiming he has a hidden radio. Culminating in Jacob’s improvised ‘broadcast’ behind the wall of an attic designed to convince his niece of their impending rescue (bringing to mind Roberto Benigni’s hugely popular 1997 film Life is Beautiful but without the same sentimentality), the film is interesting for its evocation of the power of imagination and virtuality in the form of productive lies (resulting in a sharply reduced Ghetto suicide rate). While the film typically posits the Soviets as the nascent unseen heroes of the war, in doing so it is hardly less propagandist than most Western films (and in the case of East and Central Europe, much closer to the truth).

The most interesting film, in part because it is actually about the intricate workings of the GDR, was Beyer’s Spur der Steine/Traces of Stone (1965-6), which attained an unintended ‘reflexivity’ when banned a few days into release, due no doubt to a level of moral and political nuance and complexity that almost beggars belief. The protagonists are an ambitious, seemingly liberal-reformist young Communist Party secretary newly in charge of a large construction project, and a cavalier site foreman who leads a bizarrely cowboy-styled band of troublemakers who openly disrespect Party authority and yet are also the most productive workers.

When a young female engineer arrives, both men become involved with her in different ways, resulting in an intricate and measured melodrama while also providing for a slowly building political/morality play, but without pedagogical ‘conclusion.’ By the end, the film’s founding moral universe—both political and personal—has been thoroughly unmoored (hence its banning). All this is rendered via a series of flashbacks made up of carefully framed black and white widescreen compositions. From these we gradually glean information unavailable to a present-tense ‘investigation’ scenario which the film cuts to periodically, featuring Workers Committee meetings where the young Party secretary is essentially put on trial for his personal-meets-political indiscretions (an adulterous relationship and resulting pregnancy the nexus issue).

Traces of Stone exemplifies the ability of some communist bloc films—the wishes of State producers and censors notwithstanding—to inspect an entire system at its coalface. Personal behaviour is intricately connected to political ‘responsibility’, and for long stretches here we see almost documentary images of people sitting in a drab room trying to administer the mysterious investigative mechanisms of bureaucratised socialist life. Somehow such an inquiry is made fascinating from the start, building in tension as combined with the much more elaborately staged flashback scenes. The film ultimately satisfies neither the state nor its critics, and liberal humanism in the form of what seemed a kind of love story is denied through a truly ‘modern’, very open ending. Even the ‘couple’ itself is finally unclear within an uneasy triangle that for a while proved ‘professionally’ very productive. In the end romantic love appears destroyed rather than refined, yet through the characters’ subtly transforming treatment of each other, a certain ethical gravitas, human honesty and empathy—perhaps a broader kind of sober (and properly socialist?) humanist rebellion—is strikingly voiced, even as everyone ends up ‘alone.’

Coming Out

photo Wolfgang Fritsche

Coming Out

Heiner Carow’s Coming Out premiered the night the Wall came down, giving the film’s English-language title another layer of meaning. The portrayal of East Berlin’s late 1980s gay scene is striking (as shot on location with non-actors) in a fairly clear-eyed portrayal of subcultural life. The epicentre of the film occurs when a world-weary old man in a gay bar, after being partly assaulted by the film’s self-obsessed protagonist, offers a lesson—the story of how he became a communist when trying to survive in a death camp (as the Party was the best organised resistance going). After the war he worked to overcome all oppression and marginalisation. Just as this mythology of civil rights heroism is rankling the viewer after decades of real-world Communist bloc oppression, the old man emits a cutting lament: while in time the Jews and other minorities ceased to be victims of systematic persecution, “somehow the gays were forgotten.”

This political-historical level—which may have personal resonance for its gay director—adds not only a much appreciated grit to what would otherwise have been a reasonably familiar story but also invokes the very real sufferings of Hitler’s lesser known victims (if perhaps better remembered now than communists themselves) and their less familiar German story, with strong resonance in ‘free’ countries.

The other Carow film at the festival was supposedly the GDR’s biggest domestic commercial success. Die Legende von Paul and Paula/The Legend of Paul and Paula (1973), an absurdist comedy of sorts, strongly evokes early 70s everyday life and popular culture in the GDR. It also features what we would now call ‘magic realist’ interludes. This aesthetic contrast is echoed in the film’s thematic trajectory, where post-60s romanticism operates alongside a darker tonality. At the heart of the film lies tacit acknowledgment of socio-economic difference as seen through an affair between the clearly better-off Paul, who has a mysterious government job, and Paula, who works in a supermarket, and who live across the same street from each other (the ‘communist’ element of this disparity perhaps). Their affair comes across both as a libertarian rebellion against drab working life and moral-ideological prescription (hardly unique to the GDR then). In some ways seeming more time-locked than the other films here, The Legend of Paul and Paula entertains through its charming performances and absurdist love story (though Paula dies at the end while giving birth to their child) as well as providing a scattershot meditation on the minutiae of life as played out within an urban space that appears both constantly in-construction and in-decay, a perhaps realistic portrayal of GDR city life that nonetheless also offers metaphorical suggestion.

Solo Sunny (Konrad Wolf, 1978) was another huge domestic success, while also travelling well beyond its historical and political origins, and the Prenzlauer Berg locations offer a fascinating visual account of late 70s East Berlin. This story about Sunny, who wants to be a professional singer, at first glance seems to be about ‘losers’; heroism and stardom are certainly missing, while various low-rung entertainment spaces and scenarios familiar to anyone who has ever sought a career in music are in abundance. Yet the film cumulatively offers a ‘realistic’ affirmation of human attempts to live outside the life choices apparently on offer in the society of the day, for the creative effort involved irrespective of ‘success.’ Rather than a tragedy of existential failure or a ‘lesson’ about misguided dreams of bucking against the status quo, the film offers a modest but trenchant hymn of refusal—if its enduring popularity is anything to go by—when faced with a drab social real, no matter what the tangible results.

Irrespective of their varying focus on specific historical and political issues, these films offer both rich, unfamiliar insights into the ‘other’ (in many ways suppressed, since reunification) Germany from the grave, and more broadly resonant meditations on complex social, moral and existential problems that continue to cut across time and space.

Goethe Institut Audi Festival of German Films, Sydney, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth, April 15-28

RealTime issue #91 June-July 2009 pg. 23