playing with the audience

theron schmidt: kunstenfestivaldesarts, brussels

Regarding

photo Indra Van Gisbergen

Regarding

THE ACTOR ENTERS THE DARKENED ROOM, KICKS OFF ONE SHOE, AND LIES AWKWARDLY ON THE FLOOR. SHE LAYS OUT HER SUPPLIES: DISHES OF VARIOUS POWDERS, SYRINGES FILLED WITH RED AND BROWN CREAMS, AN ASSORTMENT OF LATEX APPENDAGES WRAPPED UP IN CLINGFILM. SLOWLY, METHODICALLY, SHE APPLIES THESE MATERIALS TO HER PROSTRATE BODY. A LONG, UGLY GASH ON HER LEG. A WOUND TO HER STOMACH, WITH BLOOD POOLING BELOW HER. CLOTHES CUT WITH SCISSORS TO GIVE THE IMPRESSION OF BEING TORN. A BULLET WOUND TO THE HEAD. AND SPRINKLED OVER THE WHOLE IMAGE, A LIGHT DUSTING OF ASH AND SOIL.

This is Regarding, a performance by Isabelle Dumont, accompanied during its hour duration by Virginie Thirion’s detailed and dispassionate spoken description of a snapshot of violence along with Annik Leroy’s projected film of photographs of war atrocities being casually handled and examined. Taking inspiration from Susan Sontag’s book Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), the piece is not just about the appalling nature of war but a live experiment into our reaction, as spectators, to viewing these images. Watching Dumont’s painstaking, but painless, reconstruction, I am always aware of the conceit—the piece does exactly what the brochure tells me it will, and there are no surprises. Except one. In the midst of my inner monologue, which ranges from questions of believability (is she using too much fake blood?) to those of situation (what would it mean to do this in a public space, rather than a darkened room for a paying audience?), I am interrupted by the unexpected turning of my stomach. Maybe it’s the pus from her abdominal wound, even though I just saw it come from a jar, or the efficient cruelty of the bullet to the temple, even though this is only the representation of cruelty. The image may be fake, but my reaction is suddenly real.

Brussel’s Kunstenfestivaldesarts has a long tradition of supporting new and experimental performance—for example, this year they presented Australian artist Rebekah Rousi’s tour de force, The Longest Lecture Marathon, first seen at the 2007 ANTI festival (RT 83, p30). This festival’s many co-productions included a Singapore collaboration, The King Lear Project, directed by Ho Tzu-Nyen and filmmaker Fran Borgia. The project had its first two parts shown on successive evenings at the Kunstenfestival and the trilogy was completed at the Singapore Arts Festival in June. The first part, Lear Enters, mixes reality television with traditional Shakespeare and postmodernist metatheatrics. Structured as a live audition before film cameras that continue to prowl the theatre, three actors successively choose from a menu of Lear archetypes they will attempt: Lear as god, Lear as madman, Lear as everyman. The set design, lighting, and soundtrack change according to their choice, and they give secret instructions to the ostensibly unprepared supporting cast.

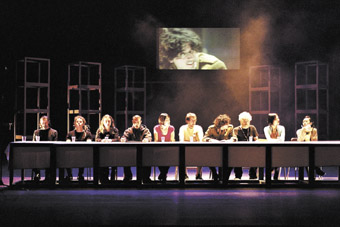

The Lear Project, Lear Enters

photo Roos Vandepitte

The Lear Project, Lear Enters

Although this live audition is clearly a contrivance, it is often convincingly spontaneous, as the Lear-wannabes improvise their audition banter and the rehearsed cast of supporting actors adapt to the shifting personalities. Additional complexity comes from interventions by an omniscient figure planted in the audience, who debates with the director during blackouts between each audition, drawing his arguments from significant works of Shakespeare criticism.

The experience is uneven, at times revelatory and at times simply heavyhanded—particularly during the second evening, which is presented as an open rehearsal within which three ‘problem’ scenes are tried in various permutations, with lengthy philosophising in between. But it saves its most wonderful moment for the very last: as we applaud what we think is the end of the production, the curtain rises on an empty stage, with all backdrops removed so that the rear wall of the building is visible. The huge stage doors open, revealing not only the cast and ‘film crew’ in the public park behind the theatre, but also small congregations from the local neighbourhood who have been enjoying a relaxing summer evening. As we continue to applaud, peering out into another world, a few of the outsiders notice us as well, and peer right back at our alien planet. It’s a stunning moment, when all the conventions and seriousness of the theatre world explode and dissolve upon exposure to the real world, and I feel caught in the act, unable to do anything more than just keep putting my hands together.

Another Kunstenfestival co-production is Rimini Protokoll’s Call Cutta in a Box, based around a one-to-one conversation with a call centre worker based in Calcutta. As with Regarding, much of the experience is what I expect it to be: I’m on the phone for most of the hour, and the conversation is directed along lines that evoke both the telemarketing profession’s appropriation of personal contact and the global economic factors of which outsourced Indian call centres are symptomatic. ‘What is the weather like where you are?’ ‘I hope you are healthy. Are you healthy?’ ‘Do you believe in reincarnation?’ I am wary of answering these questions, knowing that I am acceding to a proposition which is not yet fully known; that the friendliness with which they are asked is not genuine but designed to set up a situation in which I may find myself doing something I do not want to do.

But what’s curious about this experience is that it’s as much a comment on the conditions of theatricality as it is about economics or geopolitics. This is not so much a work about call centres, with an actor playing a call centre worker, as one in which the call centre worker plays herself. And what she is doing is always signed as play, as theatrical. This is indicated by the make-believe décor of the room I’m in, made up in exacting detail to resemble the offices of the Indian company for which she works. Or by minor illusions, charming but unambitious, such as when she claims to turn on the electric kettle remotely to make me a cup of tea. Or, most directly, when she asks me to lift up a desk plant, revealing a small box with tiny red curtains. Pulling the theatrical curtains apart reveals a web camera, via which she is then able to see me just as I am, at this point, looking at her.

Because of the doubling, in which she is herself and is playing herself, I have two overlapping frameworks within which to situate my reactions. I feel uneasy about my complicity in an arrangement where this woman is paid presumably low wages for my entertainment; but would I feel uneasy if her profession was that of actor, and if not, why not? I feel voyeuristic when she sends photographs of herself in social situations to the printer next to me, because it reminds me that she has a life outside of her job. But when an actor is working, why do I need to assume that this is what she most wants to be doing? Isn’t the idea that acting is its own reward, that the actor is enjoying revealing her true self, simply part of the ‘sale’ that the actor is trying to make with me? Finally, when this call centre worker makes her sale—which consists, she tells me afterwards, of my agreeing to sing aloud to her—she holds her phone out and asks, “Do you hear that? That is what we do when one of us makes a sale.” The sound I hear, piped over the internet from several continents away, is applause.

2008 Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Brussels: Regarding, concept, realisation Isabelle Dumont, Annik Leroy, Virginie Thirion, La Raffinerie, Brussels, May 23-31; The King Lear Project: Part 1, Lear Enters, Part 2, Dover Cliff and the Conditions of Representation, text and concept Ho Tzu-Nyen, direction: Ho Tzu-Yen, Fran Borgia, KVS, May 24-25; Call Cutta in a Box, concept Rimini Protokoll (Haug/Kaegi/Wetzel), Monnaie House, May, 9-31

RealTime issue #86 Aug-Sept 2008 pg. 55