performance on DVD: archive alive

archive alive: cage, fluxus, foreman

AT LONG LAST, DVDS OF CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE AND INTERVIEWS AND DOCUMENTARIES ABOUT OR WITH THEIR MAKERS FROM THE LAST 50 YEARS ARE BECOMING AVAILABLE TO DEVOTEES OF ART THAT CHALLENGES AND INSPIRES AS IT TURNS YOU UPSIDE DOWN AND SOMETIMES INSIDE OUT. ON THE DOWNSIDE, THE DVDS ARE EXPENSIVE COMPARED WITH FEATURE FILM AND DOCUMENTARY RELEASES AND NOT ALWAYS EASY TO ACCESS. THEY EMANATE FROM SMALL-SCALE PRODUCERS AND DISTRIBUTORS IN BERLIN, NEW YORK, TOKYO, and ALSO FREMANTLE WHERE AUSTRALIA’S CONTEMPORARY ARTS MEDIA HAS A LARGE CATALOGUE RANGING FROM GROTOWSKI TO JENNY KEMP AND FORCED ENTERTAINMENT. REALTIME WILL REVIEW NEW DVDS AS THEY BECOME AVAILABLE.

Foreman Planet

Interview with Richard Foreman

Director Kriszta Doczy

DVD, 2004, recorded 2003, 75 mins

Private $65; Schools $AUS200; Tertiary education $AUS250

Plus GST, packaging and post

Contemporary Arts Media

www.hushvideos.com

Foreman Planet is a 75-minute documentary DVD on the life and work of Richard Foreman—10 time OBIE award winning writer, director, designer and founder of his own influential Ontological Hysteric Theater, in New York.

“Consciousness… spiritual consciousness… to know the unknowable other…” is what Richard Foreman describes as the foundation and ultimate subject of his life and work. His is an investigation of the unconscious that is outside of culture and conditioning which is part of the world that we can understand. To achieve this his theatre attempts to dismantle all “reference points.”

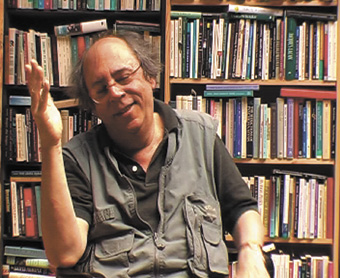

Richard Foreman, Foreman Planet

Foreman equates his own investigations with what he calls a “negative theology,” which is to know God or the Other by knowing everything that is not God or the Other. His two roles of writer and director encapsulate this binary—as director he embodies the ego and performance of being in the world, while the writer remains in the realm of the unconscious. Foreman states that his talent is for “sensing this underlying, unattainable, continual eruption of new things from different directions that are constantly colliding… sensing a rhythm… sensing a responsiveness.” Finally, concerning both the language of his theatre and the language of the world, Foreman articulates that language is, for him, “a statement that is as if dropped to the bottom of a well, where its statement hits, and reverberates…” The language of his theatre attempts to deal with such reverberation.

The style and presentation of this DVD document—and the nature of the questions from interviewer Kriszta Doczy—amounts to more an introduction to the man and a little of his work than an in-depth study. Foreman describes in detail his creative impulses, defines his methodologies and talks about psychic freedom, realism, objects and influences. The sun slowly fades from afternoon to evening as Foreman sits talking in his New York loft. The high quality of Paula Court’s photographs of his productions give the DVD an elegance otherwise lacking. Sadly, for whatever reason, no filmed examples of his work are shown.

In response to the interviewer’s somewhat basic questions, Foreman’s discourses (sometimes rants) are full of linguistic colour and energy. The questions are often used as section titles, giving the DVD the feeling of an educational aid rather than an imaginative response to Foreman’s work. Nevertheless this DVD is a very valuable introduction to the thinking if not the work of an important American contemporary artist.

Max Lyandvert

John Cage Performs James Joyce

Takahiko Iimura

DVD, 2005, recorded 1985, 15 mins, B&W

Private $US100; institutions $US400

www.takaiimura.com/home.html

Taka Iimura is a senior figure among contemporary Japanese artists and has been working with film, sound and video since the 1960s. He was one of several Japanese who, coming from a 20th century tradition of avant-garde intervention, contributed to the Fluxus (NYC) group in the 60s. As a senior figure (1912-1992), active experimentally since the late 30s, John Cage is the subject of a video portrait shot by Iimura in 1985, released in 1991 and made available on DVD in 2005.

Like many media artists, Iimura made recordings of contemporaries and their work. Alongside his making of artworks, portable video enabled documentation (and general note making) more economically than film. As the cycle of experimentation moves through another generation, glimpses of precursors through archive recordings of this kind help ground artists’ surviving words and artworks.

Cage had a long-standing fascination with the work of James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, forming the basis of many works, the best known of which is the Roaratorio—an Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake. Commissioned by German radio and IRCAM in Paris the sound recording was completed in 1979, lasted about an hour and was a 62 track mix of the sounds referred to in the text, the text itself as prepared (using a mesostic system) and read by Cage, together with music by the traditional Irish musicians of the day.

Roaratorio is one of the classics of Cage’s oeuvre and in Iimura’s 15 minute recording Cage presents the core of the spoken part of the work. Its composition, like many of his other works, is aided by the I-Ching. Here he briefly explains that none of the sentences (sic) in Finnegans Wake are selected, only words, syllables and letters from different pages according to the chance decisions made by consulting the I-Ching and its representational hexigrams. In this way the 624 pages of the book are compressed into 12 pages of text, and it is one of these pages that we see him holding. He reads from it, sings it, then hustling close to the camera and its microphone, whispers it. At the bottom of the screen are superimposed, each time, two lines of sub-titling synchronised with the text he is using.

Iimura’s presence is felt but not seen, though we hear him responding to Cage’s explanations at the outset. Cage’s voice is not strong (he is in his seventies) and we strain to hear him against the noise of New York traffic in the background coming through the window of a sunlit room. His demeanour remains buoyant, at one point making light of a fumble he makes with a watch he is holding, an event incorporated into the flow of the tape. Like so many of his initiatives, the line between the artwork and its making is blurred, a state aided and amplified by Iimura’s collaboration in its making.

Mike Leggett

This review first appeared in Leonardo Vol 40, No 1, 2007.

Fluxus Replayed

Takahiko Iimura

DVD, 2005, recorded1991, 30 mins, B&W

Private $US100; institutions $US400

www.takaiimura.com/home.html

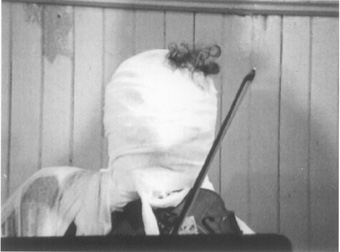

oko Ono, Skypiece for Jesus Christ (1965)

In Fluxus Replayed, Taka Iimura documents an event in 1991 held to reproduce historical performances by NYC-based Fluxus artists of the 1960s. The S.E.M Ensemble together with some of the Fluxus artists themselves, perform works by Nam June Paik, Yoko Ono, Dick Higgins, George Brecht, Allison Knowles, Ben Patterson, Jackson Mac Low and Emett Williams. Iimura has edited together the sounds and images captured by two cameras as raw evidence of the goings-on with scant regard for the conventions of continuity editing, thus maintaining the document in the space between the moment of recording and that of viewing. Time compression is only obvious in Ono’s SkyPiece for Jesus Christ (1965) as the baroque instrumental ensemble are wound around with white paper, accumulated as a series of jump cuts to the point where their music is reduced to a series of bumps and scrapes before being man-handled off the stage, still attached to their chairs and instruments.

Again, Iimura gives some idea to younger generations of how these early precursors to contemporary performance art appeared to audiences, in a setting typical of the genre—church hall ecclesiastical architecture, painted walls, wooden floor. Though much of this work was sound-based, produced collaboratively for group performance using chance determinations and framed with a sense of the aesthetics of noise, the written scores or instructions for each piece may well have satisfied many members of the audience. Glimpsed in the background, some walking around, others squirming in their seats, the probably overlong evening has been bravely foreshortened into a useful 30-minute document by the man with the video camera.

Mike Leggett

This review first appeared in Leonardo Vol 40, No 1, 2007.

RealTime issue #77 Feb-March 2007 pg. 48