Performance art in the experience economy era

Ben Brooker: PP/VT (Performance Presence/Video Time)

Ray Harris, Glitter Vomit (video still) single-channel HD video, 5.36 mins

courtesy of the artist

Ray Harris, Glitter Vomit (video still) single-channel HD video, 5.36 mins

Performance art’s latest international revitalisation—in part a reaction against years of object-based spectacle in the art museum, and reflecting a surging interest in a dematerialised, experience-orientated art—has been well documented. Amelia Jones has argued that the “wholesale resurgence” of the genre borders on obsessional in the art world, while Diana Smith, member of Sydney-based performance art collective Brown Council, noted in a 2013 essay, “In Australia there have been new levels of visibility for performance art in major institutions across the country and with it, as curator Reuben Keehan remarks, ‘a greater purchase among a younger generation of practitioners’.”

This younger generation features heavily in PP/VT (Performance Presence/Video Time), which brings together at the Australian Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide a gallery-based exhibition with a focus on new works and delegated performances, and video works and installations that include documentation of live events, and performances, such as those by South Australian Ray Harris, made specifically for screen. Only four of the exhibition’s participating artists—Jill Orr, Arthur Wicks, Jill Scott and Eugenia Raskopoulos—could be said to represent Australian performance art’s old guard.

“I think my brief to myself,” curator Anne Marsh explained to me, “was to have some kind of an overview of what’s happened in the last 10 years or so and to showcase the younger generation.” Key to this are a number of delegated performances, a form continuing to gain traction in the art world even as experienced practitioners, perceiving inauthenticity and commodification, resist it. “On one level,” Marsh comments, “delegated performance is a kind of homage to the original, on another level it critiques the original, but because it’s a copy it also makes it kind of cleaner and more digestible for a commercial market because we already know what the artist did—the edge is off it.” Few of the older generation artists whom Marsh asked were interested in doing a delegated performance but, she continues, “I really wanted to include some artists in their 50s and 60s, to give the visitor to the gallery an indication that performance art actually has a history in Australia.”

This history’s documentation is still being caught up on, as evidenced by the fact that Marsh’s comprehensive survey of Australian performance art, Body and Self (1993), remains the only publication of its kind and is out of print. There are signs that a new wave of scholarship is emerging—PP/VT’s companion book is Marsh’s internationally-focused performance art survey, Performance Ritual Document (2014) and Edward Scheer’s The Infinity Machine: Mike Parr’s Performance Art 1971-2005 (2010) is the first major monograph on an Australian performance artist—but Marsh’s desire to see the closing of “a gap in Australian art history” remains unfulfilled despite performance art’s increasing assimilation by the art establishment into its mainstream ‘white box’ spaces, concomitant with growing scholastic attention and cultural cache. (As I write this, two out of the three top trending items among my Facebook friends’ feeds are about performance artists, Marina Abramovic and Emma Sulkowicz.)

“Why do we have a new wave of performance art?” Marsh asks rhetorically. The AEAF is in its 41st year of operation, and we are in an upstairs office at the foundation’s premises in the Lion Arts Centre on North Terrace. Below us are the gallery space and Dark Horsey bookshop, where the shelves are lined with art magazines, cultural studies classics and slim volumes of short-run poetry. “I think society is ready for it because we live in an experience economy. I was in Sydney at the end of last year and I was talking to a commercial gallery director. She said to me “I can’t sell paintings anymore—the rich people want ‘experience’.”

The recent record-breaking sales at auction of works by Picasso ($106.5m) and Alberto Giacometti ($141.3m) notwithstanding, there is ample evidence that the pendulum has indeed swung back towards the ephemeral and the experiential, and away from the exalted art object à la Damien Hirst’s zenithal For the Love of God (2007). We might point to Marina Abramovic’s international renown—projected far beyond its early cultishness by the weeklong series of re-performances, Seven Easy Pieces performed at New York’s Guggenheim in 2005—or the voguishness of Kaldor Public Art Project’s 13 Rooms (2013). The latter’s proliferation of delegated performance and framing of its participants as ‘living sculptures,’ redolent of masculinist formalism and exploitation (as well as, no doubt, the exhibition’s suspicion-fomenting popularity with Sydney’s general public), rankled some critics. (See performance artist Barbara Campbell’s response in RT115).

Queensland-based duo Clark Beaumont, comprising QUT graduates Sarah Clark and Nicole Beaumont, became, according to Marsh, famous through their contribution to 13 Rooms, Coexisting. The piece, performed for 8 hours a day over eleven days, saw Clark and Beaumont intertwined on a plinth slightly too small to comfortably accommodate two people. The duo is represented in PP/VT by Hold On To That Feeling (2013), a dual channel video installation in which they appear on a sports field in the normatively masculine pose assumed by Judd Nelson’s character John Bender at the end of the 1985 film The Breakfast Club: legs slightly apart, head tilted insouciantly, one fist raised victoriously against a clear blue sky. In its excruciating protraction, a gesture ordinarily fleeting and associated with the traditionally homosocial team sport, becomes emphasised as, in Judith Butler’s terms, a constitutive performance of gender.

Another notable work for video is Brown Council’s This is Barbara Cleveland (2013, available to view in its entirety online at www.browncouncil.com). The 16-minute video, which, as Marsh put it to me, trades on Allan Kaprow’s notion that “some of the best performance art you’re ever going to know about probably exists only through rumors,” is a part-mockumentary, part-art film about the life and work of fictitious performance artist Barbara Cleveland (the surname is an in-joke – Cleveland Street housed Sydney’s Performance Space from 1983 to 2007). “We know,” says talking head Kate Blackmore, “that Barbara Cleveland was an Australian artist working primarily in Sydney in the late 1970s and she disappeared in 1981.” Various mouths in close-up, like that in Beckett’s Not I, intone extracts from lectures Cleveland wrote during her late 1970s/early 1980s heyday and that were discovered in a box in 2011. Few traces remain—just the typed out lectures, and a handful of poor quality photographs —of Cleveland’s progression from Mike Parr/Peter Kennedy-esque idea demonstration works to the ritualism and simple gestures of her later, strongly feminist oeuvre.

Jill Scott delegated to Mira Oosterweghel, Taped 2015, documentation of live performance at AEAF (Adelaide) 14 May, 2015

photo Alex Lofting

Jill Scott delegated to Mira Oosterweghel, Taped 2015, documentation of live performance at AEAF (Adelaide) 14 May, 2015

Brown Council’s fascination with the mythical aura lent the performance artist by the genre’s sparse documentation and (not unrelated) marginal status in critical discourses is also the basis for a participatory live work, The History of Performance Art. In the bookshop, Council members Frances Barrett, Kate Blackmore, Kelly Doley and Diana Smith share a circle of chairs and a microphone with audience members as stories of witnessed performance art works, both recent and from long-ago, often half or barely remembered, are traded. I duck in and out of the always lively conversation, caught between it and Jill’s Scott’s Taped (first performed in San Francisco in 1975, here delegated to Mira Oosterweghel), taking place next door in the gallery. Steve Eland, AEAF director since 2014, remembers a senVoodoo performance during which an audience member licked their finger after touching it against a wall splattered with the artist’s blood. Other names drift in and out of focus—Andre Stitt, Bonita Ely, a hairdresser called Pluto who “threw syringes into his arm”—and in the interplay of memory, hearsay and conflicting knowledges new myths are born, others renewed, still more revised or gently skewered as a sort of communal oral history is lovingly educed.

A different kind of historicisation—one defined by Derrida as the “illumination of the beginning of things”—occurs with Marsh’s curation of archival and documentary video. The oldest, shot in short bursts on a Super 8 camera, indexes two performances by Arthur Wicks from 1981: Chicago Cake Walk, in which Wicks “walked rather precariously along the iced edge of Lake Michigan in Chicago,” and Measuring Stick – From Inside the Black Box, in which the artist awaited the arrival of high tide on beaches in New South Wales and South Australia. More recent works represented by documentary video include Fiona McGregor’s You Have the Body (2008), a tripartite performance about unlawful detention in Australia based on a one-on-one encounter, and Frances Barrett’s My Safe Word is Performance (2014), a difficult to endure body art work in which Barrett is repeatedly slapped on bare legs for around 20 minutes by a male collaborator who has been instructed that he can, in addition to slapping, spit or urinate on Barrett, hit or blindfold her. Technologically mediated though the spectator’s experience of the latter is, its ability to disturb persists, reminding us of Amelia Jones’ contention that: “While the live situation may enable the phenomenological relations of flesh-to-flesh engagement, the documentary exchange (viewer/readerdocument) is equally intersubjective.”

Jones’ “live situation,” whatever we are to make of its ontological distinctiveness (a one-day symposium, You Had To Be There, was dedicated to this question on the exhibition’s penultimate day), is generated in PP/VT by the delegated (the above-mentioned Taped, Kelly Doley’s Cold Calling a Revolution, delegated to Ashton Malcolm) and the mediated though real time (Patrick Rees’ Narcissus Aquaticus Solipsistus Cogitus—Live from the Reflectadome!, beamed into the gallery from Los Angeles via an almost unintelligible Google Chat feed) and a whimsical, rambling monologue that took place during the symposium and in which a “present but absent” Arthur Wicks, represented by an empty suit, broadcast from “subatomical space” having been “reduced to just a handful of soundbites.”

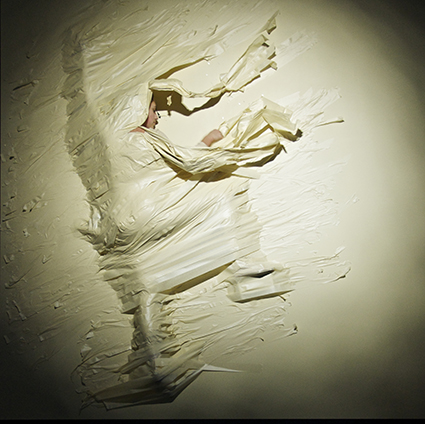

Jill Orr’s Trilogy III—To Choose singularly recalled the shamanism and ritualism that was central to much of the performance art of the 1970s. Evoking pagan ritual, the artist, swaddled in white cloth and suspended by means of a heavy underarm rope, dismounted a boulder and approached the audience, leaving behind a striking outline of her body on a grid of panels made an eerie green by washes of phosphorescent paint. A thrashing, expurgatory choreography followed, after which Orr ceremonially removed her cloth foot bindings and serenely exited the space, the afterimage of her body still visible on the grid, her presence continuing to haunt the gallery amid the dispersing crowd.

Who knows what of PP/VT will pass into the collective imaginary, will be forgotten, absorbed, reconstituted? Its idiom is an expanding and increasingly commodified one—for proof of this, one need only point to Marina Abramovic’s impending, high-profile works for Kaldor Public Art Projects and MONA, or recent exhibitions and festivals in Brisbane (Trace: Performance and its Documents at GOMA, EXIST-ENCE 5) and Newcastle (Enduring Parallels at The Lock-Up)—but the market is too fickle and restless an entity to sustain performance art’s resurgence for long. Only cultural memory can do that, somewhere in the complex and fraught mix of rumour and document, visibility and erasure, that has always been the genre’s terrain. We Create the Image Together was the subtitle of an earlier iteration of Orr’s Trilogy. Indeed we do.

PP/VT (Performance Presence/Video Time), curator Anne Marsh, Australian Experimental Art Foundation, Adelaide, 1 April-16 May

RealTime issue #127 June-July 2015 pg. 12-13