out of the ordinary

jane mckernan: interview, rosemary butcher

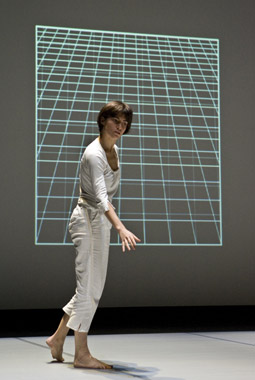

Elena Gianotti in Episodes of Flight, 2008 by Rosemary Butcher and Cathy Lane

courtesy the artists

Elena Gianotti in Episodes of Flight, 2008 by Rosemary Butcher and Cathy Lane

LATE LAST YEAR, CRITICAL PATH HOSTED TWO WORKSHOPS BY CHOREOGRAPHERS WHO MAKE VERY DIFFERENT WORK, BUT WHO ARE LINKED THROUGH A COMMON EXPERIENCE OF EPIPHANY WHEN MEETING THE WORK OF JUDSON CHURCH CHOREOGRAPHER, YVONNE RAINER.

French choreographer Xavier Le Roy, in his piece, Product of Circumstance, cites performing in a company which recreated Rainer’s works as a major shift in his understanding as a dance maker (and was introduced to audiences in Sydney by Amanda Card with a lecture that began with Rainer’s famous No Manifesto). UK choreographer Rosemary Butcher, who uncannily describes her meeting with Rainer as not so much luck but circumstance, is upfront about how her time in New York in the late 60s and early 70s profoundly changed the work she made on her return to the UK.

Butcher was in Sydney with her collaborative partner, composer Cathy Lane, to lead a month-long research project through Critical Path and Campbelltown Arts Centre (CAC) called the Composers and Choreographers Lab, in which I participated and the results of which were screened as part of CAC’s What I Think About When I Think About Dancing exhibition. Despite having made work over the last 30 years and being one of the leading proponents of new dance in the UK, Butcher’s choreography is not well known in Australia. This is possibly because she has constantly challenged conventional forms of dance, which makes her work appear somewhat difficult (a recent review in London admits that her audience is small but dedicated), and because she has only been touring outside of the UK since 2000, after making her first piece in collaboration with Cathy Lane, Scan.

The effect of working with Rainer in New York for Butcher was the total shift in understanding as to what sort of movement could constitute dance, and the performance of this dance outside of the conventions of the theatre. Butcher says, “I do not know, in my background, why I should have been so suddenly so disconnected with the formal and the theatrical, but I responded to another way of thinking, and I think, felt as if I could create with that in mind in a much freer way than if I’d stayed within a wider construct.” The first work Butcher made in the UK after this period was performed at The Serpentine Gallery at a time when, she says, “everybody seemed to be working for free and there was sort of an idea that things just happened at that time and then they disappeared. They weren’t recorded very well. There was no sense of continuity but there were a lot of people putting things on.”

This initiated her long interest in researching “how to transfer the ideology and methods of making visual art into the dance world and into the choreographic world”, which has led her work to a focus not only on the visual but also on notions of space and duration.

“[F]or a long time the formal time-based way you come to a show and you’re presented with something and you clap and you go away [has] always slightly worried me, though I’m a performer at heart and a director and love the theatre…[But] I’m less interested in it and would like the work to be far more along the traditions of how visual art is viewed, where you spend as long or as little time as you want within your experience, but it’s entirely up to you as to how, when, where etc that you experience it. You’re not brought in and curtailed and asked to see something at a particular time.”

Butcher’s movement palette consists of a dancerly version of pedestrian or everyday movement, but requires a precise and detailed virtuosity from her performers through her choreographic treatment of this material, which is expanded and amplified through repetitions and changes of speed. “There is a consideration of duration. There’s a consideration of how a particular framework will allow something to be seen very particularly or, if you increase the number of times that you see it, the volume of the experience is bigger. Instead of changing and developing an idea, to me it’s very interesting if it recurs. The scale is bigger though in fact the movement is still the same.”

Rosemary Butcher and Cathy Lane, What I Think About When I Think About Dancing Artist Talks

photo Heidrun Löhr, courtesy Campbelltown Arts Centre

Rosemary Butcher and Cathy Lane, What I Think About When I Think About Dancing Artist Talks

However, for Butcher the choreographic material is only one part of her work, and she contends that it is set up to be watched with other layers and frameworks. She has consistently collaborated with artists from other fields, including contemporary art, architecture and music, and has worked with composer Cathy Lane for the last 10 years. Their collaboration is particular in that they begin discussing concepts and ideas together, swap books and research material throughout the creative process but make their work in parallel, only bringing it together in the last weeks. This allows an autonomy of form, and the audience is able to watch the dance in relation to the music and visual elements, rather than seeing them as a whole. Butcher says she wants her audience “to view the work as a non time-based medium, that they’re experiencing sensation and feeling, and that all the ideas within the making are shown through the way the performance is executed. Of course I want people to understand it, but I also don’t expect it not to be difficult. And people do get lost within it. There’s a lot going on but it doesn’t register with everyone; but then I wouldn’t want to lead people directly to it, so I have to take the consequences.”

Rosemary Butcher and Cathy Lane Residency: Composers and Choreographers Lab, Critical Path, Campbelltown Arts Centre, What I Think About When I Think About Dancing, Campbelltown, Sydney, Nov 16-27

RealTime issue #95 Feb-March 2010 pg. 32