Obituary: Benjamin Grieve

Fiona Winning

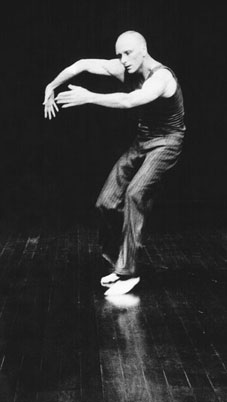

Ben Grieve

photo Heidrun Löhr

Ben Grieve

Ben Grieve was an astonishing artist and a dear friend.

He was raised in Canberra, lived a long time in Sydney, then in Berlin for 5 years before returning to Australia last May. On October 2, he went missing. His body was found on November 14 at Manly. He was buried in Canberra in December, at a ceremony attended by his partner Martin Del Amo, his family and friends. Nobody knows of his last hours. We do know he’s gone.

Ben was an actor, dancer, performance maker, musician, singer, writer and thinker. All these skills coalesced in an idiosyncratic and utterly memorable marriage of physicality, musicality and intellect. It made him a wonderful artist. In performance, Ben was electric, elastic, alert. He had a kind of jerky elegance, an ability to move in multiple directions simultaneously, unwinding minute gestures to reveal an endless array of tiny narratives across his body.

Ben began training and performing in Canberra in 1983 with Canberra Youth Theatre’s Troupe. He went on to perform with the Ensemble Theatre Project, Fortune Theatre and People Next Door. In the late 1980s and early 90s he worked with an incredible range of artists and performance makers, including Sydney-based companies Death Defying Theatre, Entr’acte, One Extra, Stalker and Nikki Heywood. He performed at Performance Space, in schools and outdoors, in international festivals, in Europe and with his band, The Blue Crush Club, in pubs, clubs and at parties.

In the late 90s Ben’s desire to train, rethink his practice and broaden his professional horizons took him to Europe. He freelanced in Germany, Belgium and Holland with small ensembles and premier companies such as Schauspielhaus Hamburg and Company Felix Ruckert.

Most recently, in Sydney, Ben performed exquisitely in Rosalind Crisp’s tread at Performance Space, reminding Australian audiences of what we had missed during his 5 years away. He also worked as the physical trainer on The Living Museum of Fetish-Ized Identities, generously offering his skills and encouragement to his peers. Around this time he also worked as a community carer.

I’m lucky to have worked with Ben in the early 90s. As with many of his colleagues, we became friends. We’d spend intense times together, then stay in irregular contact, but were always able to pick up where we left off, with one intimate detail or another, sitting in the kitchen chatting, gossiping, giggling into the night about recent exploits and dilemmas—personal and professional. We’d compare work experiences and aspirations, our states of hair, insomnia and relationships.

Ben was unencumbered by worldly possessions—though he was in his own way extremely stylish in his endless collection of midriff tops. He was encumbered with enormous desire. Desire to participate in our world meaningfully but lightly. Desire to make great work. Desire to critically unpick his surroundings, himself, and all that makes up this complex culture.

He interrogated life in general through his performance work and learnt much about his own life through performing. He was always interested in work with political and emotional depth. Making work was serious business for Ben. He gave it a lot. He was wickedly funny and could make tragedy, confusion or loss seem hilarious on stage, in the dressing room, at the after party, even at 6am boarding the minibus as it began its trip to Penrith for an 8.30am school show.

He was simultaneously generous and demanding of his collaborators. Demanding in the sense that he wanted to collectively crack it, to break through a work to create heart and intellect. He wasn’t petty or sycophantic. He wasn’t interested in industry success or recognition or a cosy career path. He was driven to make great, urgent and beautiful work. And he often did.

Many of his collaborators and friends gathered at Performance Space at the end of last year to farewell Ben and engage in a collective act of remembering. While mostly Sydney-based people were able to attend, the event reminded us of how many worlds Ben inhabited over time. He passed through many people’s lives but always with an intensity that was unforgettable. Perhaps Clare Grant put her finger on it when she described the effect of Ben’s reflexivity on his collaborators/ mates: “He watched what he made through a lens that was so complex you found ways of seeing you didn’t know you had.” There’s no doubt this was hard work for him.

A few days before he disappeared, Ben joined the closing night party of The Living Museum. He was elated and as usual, wickedly funny. He was wearing a pink wig, dancing around the space, giggling as he sang cheesy pop songs. He said goodbye at least 17 times.

When I spoke recently with Jane Packham, a very old friend of Ben’s, I asked her the name of a show that she and Ben were making in the late 80s which I never saw but heard so much about at the time. She laughed and said, “I don’t remember, and if you’d asked Ben he probably wouldn’t have remembered. All I know is that I loved him with all my heart.” For many of us whose relationships with Ben began through making work but extended into intense and enduring friendships, this is our experience also—we know we loved him and we know we miss him.

The photograph of Benjamin Grieve by Heidrun Löhr was taken at Rosalind Crisp’s tread, Performance Space in May 2003, his final performance.

RealTime issue #59 Feb-March 2004 pg. 11