New horizons for audio-visuality

Joel Stern writes from and performs at Transacoustic, New Zealand

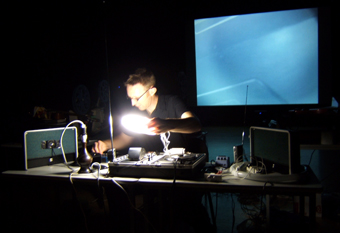

Andrew Clifford, Electric Biorama Spectacular

Auckland’s Trans-Acoustic festival describes itself as an experimental platform for the fusing of sensory impressions. A brainchild of Zoe Drayton, founder of Audio Foundation, a resource hub for experimental audio culture in NZ, Trans-Acoustic featured 3 nights of performance by Australian and New Zealand artists who explore the range of possible meanings produced by simultaneous projection of sounds and light/images.

Auckland-based artist and writer Andrew Clifford opens proceedings with The Electric Biorama Spectacular, a meditative performance structured around shifting patterns of radio static subjected to signal interference from flickering neon lights. The piece hinges on the mechanics of transmission and Clifford expands the sonic dimension by placing tuned receivers throughout the audience and beaming them his distressed signal, causing a lovely flood of soft high and low frequencies to circulate throughout the room. In common with ‘trans-missionary’ organisations like Instrumental TransCommunication (ITC), Clifford considers his performance a kind of “séance, trying to materialise manifestations of invisible forces in the room”, and although tonight the ghostly murmurs are barely audible, a certain presence is definitely felt.

An exception to the sound/light bloc is an Auckland group, A Presentation of Bees and Spandex, whose chemically treated, melting 16mm films emit a discernibly noxious scent which hangs in the air during their set. A collaboration of Eve Gordon’s projections and Sam Hamilton’s sound, Bees and Spandex recall the multi-projector experiments of Expanded Cinema pioneers at the London Filmmakers Co-op, especially Malcolm Le Grice’s explorations of structural indeterminacy and chemical/material investigations. Hamilton introduces the performance as the “rejuvenation loops”, referencing artist William Basinski’s “disintegration loops”, in which fragments of looping audiotape are gradually degraded; a blurry sonic meditation on the fragility of materials. Bees and Spandex reverse the process, cleaning their crudely spliced filmstrips of chemical residue as they’re hand cranked through the projectors. Despite predicable technical difficulties, the celluloid does slowly ‘rejuvenate’, revealing a bizarre montage of zoo animals on parade, accompanied by a crackly, whistling circus-like soundtrack.

Botborg, a Brisbane cracked video duo who claim to research the ‘occult’ science, “Photosonicneurokineasthography (psnky)”, established by Dr Arkady Botborger (1923-1981) close the night. Whether Dr. Botborger has actual scientific legitimacy is doubtful, though on this evidence, his contribution to the ‘visual music’ tradition might be worth reconsidering. Botborg’s work is aggressively complex and occasionally frightening. On first impression they come off like a nasty update of legendary animator Norman Mclaren’s handmade synaesthetic masterpiece Synchromy (1971), all collapsing blocks of digital colour and glitched synthetic sound. However, Mclaren treated his materials with an artisan’s care, whereas Botborg subject theirs to a kind of audio-visual bludgeoning. At the intense climax Botborg’s images seem to erupt and spasm viciously, as if attempting in confusion to exit the screen and drench or absorb the audience. The experience is in a way profoundly televisual rather than cinematic, like a hidden station that suddenly targets vulnerable 4am minds when everyone else is sleeping. We all know that too much idiot box is bad for us, and we remember from Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983) how easily a fuzzy collapsed signal transforms into deadly transmission. In all their abstraction, Botborg manage to distill some of that creepy fear.

Trans-Acoustic day 2 begins with improvising ensemble, Plains, the supergroup of Auckland’s post-digital music scene, comprising Tim Coster, Richard Francis, Rosy Parlane, Mark Sadgrove, Clinton Watkins and Paul Winstanley. In spite of their monstrous sonic potential Plains plot a restrained and careful path, cultivating a buzzing, humming group-sound full of gentle spikes and fluctuations in tension and volume, all controlled by an array of light-sensitive transducers exposed to various flashing trinkets. Winstanley brings the cleverly structured set to its finale, activating a set of twinkling Christmas lights spread across the performance area. The lights blink festively, their signal bleeding into the sound as rhythm fused across senses.

A History of Mapmaking is Auckland programmer/composer Rebecca Wilson’s work for amplified cello, light-controller, video sensing software and digital audio processing. Formerly “director of leaves and petals” at the experimental Dutch institute STEIM, Wilson possesses high level computing knowledge that would leave most lost and dizzy, but even she seems perplexed, when shortly into her set, things begin to seriously malfunction. So A History of Mapmaking becomes a series of tantalising previews, punctuated by breaks for emergency rewiring. In full flight, Wilson’s project combines beautifully abstracted cello with austere, line-based graphics; a striking synthesis. Tonight, with admirable composure and humour, she adds impromptu problem solving to her live repertoire.

Melbourne artist Robin Fox’s astounding work with the Cathode Ray Oscilloscope has developed to a point of almost incomprehensible complexity and beauty. For those familiar with Fox’s project, the great pleasure has been seeing it evolve over 2 years. However, at this late stage of development it’s hard not to envy the Auckland audience experiencing the work for the first time. The technical basis is relatively simple: computer generated audio flows directly into an oscilloscope and the electricity excites a single light photon (a bright green dot) which moves frantically around a phosphorous screen. American abstract filmmaker Mary Ellen Bute tried something similar in Abstronic (1954) (featured in ACMI’s recent White Noise exhibition), but where she played on her oscilloscope a charming number called Ranch House Party, Fox blasts his machine full of scorching electronic frequencies and shards of fractured noise. He might also have dipped the oscilloscope in pure LSD, because on this occasion the “single light photon” embarks on an ‘innerspace’ trip so ecstatic it makes the climax of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey feel like an uneventful stroll to the corner store. Trying to describe Fox’s images is difficult, but one has the sensation of moving exceptionally rapidly through enclosed twisting passages, bursting momentarily through logically impossible space, and being constantly smacked back into cosmic freefall. Perhaps this is what it’s like to be a pinball?

Auckland artist Adam Willetts opens night 3 with his unusual setup; a desktop lamp and a bunch of bubble-enclosed solar powered robots placed on the strings of a distorted electric guitar. Once energised, the pink robot-bubbles, each the size of a clenched fist, proceed to twitch, bounce and jerk all over the highly amplified instrument. Robot music was once supposed to sound clean and precise like Kraftwerk, but Willett’s robots are punkish and temperamental, hacking out epileptic staccato rhythms interspersed by waves of feedback. Their creator is happy mostly to observe, tweaking sonic parameters here and there and, most vitally, ensuring the intoxicating solar energy supply doesn’t run dry.

The Professionals (Nick Cunningham and Helga Fassonaki) follow with their beguiling mix of the arcane (vintage oscillators triggered by flashlights) and the cheap (homemade sound-generators in polystyrene containers), all of it hooked up to an old monitor which throws faint green flashes across the theatre walls. Cunningham’s droning electric guitar accompanies, nicely offsetting the squiggly electronics. Once again, a literal sound/image connection has been constructed; ie, a sound signal is output directly into a visual input or vice versa. This kind of signal synaesthesia is undoubtedly a major theme of the festival.

The evening’s finale was Abject Leader featuring this writer’s improvised soundtrack, and the multi-projector 16mm films of Sally Golding. Our collaboration is almost traditionally ‘cinematic’ in that the sensory point of contact isn’t technical, but essentially thematic; a shared exploration of memory, duration and dream consciousness. My own sounds are largely ‘Made in NZ’: the inside of a beehive, a recording made with the assistance of a friendly South Island beekeeper a few days earlier, and the resonant frequencies of a gong scavenged from Auckland’s premier authentic Chinese import warehouse, Wah Lee.

Trans-Acoustic is one of many new festivals specifically exploring audio-visuality; the relationship of sounds to images. This curatorial tendency is a positive for both artists and audiences, bringing into sharper focus a vast area of research and practice, informed equally by avant-garde traditions in film, music and visual art, and grounded in the creative engagement with both old and new technologies.

Trans-Acoustic Festival, Auckland, New Zealand, Dec 8-11, 2005

www.transacoustic.org.nz/

RealTime issue #71 Feb-March 2006 pg. 12