More than meets the eye

Virginia Baxter, Keith Gallasch, Point of View

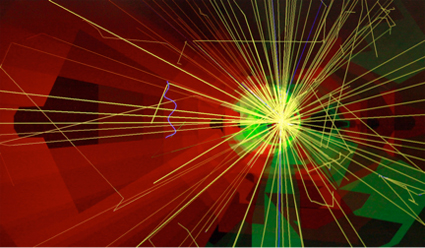

Volker Kuchelmeister, A dromological vision machine, 2013, Interactive video installation

courtesy the artist

Volker Kuchelmeister, A dromological vision machine, 2013, Interactive video installation

Point of View at Kudos Gallery proved to be one of the more intriguing exhibitions in ISEA2013, testing perceptual processes and ideas, if, frustratingly without the aid of floor notes or catalogue.

Volker Kuchelmeister

The title of Volker Kuchelmeister’s Juxtaposition refers to his adroit and witty merging of scenes filmed by the artist in Hong Kong and on a sojourn in the World Heritage wilderness of south-western Tasmania.

Wearing 3D glasses the viewer—or stroll with a friend—activates the work by means of gripping a horizontal rod that rotates the cylindrical projection surface as you move outside it at your own speed, observing a continuous stream of images over some 12 leisurely rotations.

The magical journey begins and ends in a Hong Kong graveyard. Along the way are regular reminders of the contested space between built and beautiful natural environments and the mostly uncomfortable encroachment of one upon the other, though the seamlessness of the transitions makes for some pleasing possibilities: concrete edifice melding into wilderness; natural rocky outcrop slowly encroaching on a hill of head-stones; and a tree trunk that has forced its way through an council street map.

The simple design of the structure along with the successful use of 3D and accompanying soundscape makes for an absorbing experience. For the 10 minutes or so it takes for us to make our way through this constantly unfolding diorama—and for some time after—the cool dark of Kudos gallery becomes animated urban jungle. This disorienting phenomenon—partly induced by walking in circles—has apparently been noted and scheduled for future exploration by Kuchelmeister, a prestidigitator of perception with an impressive repertoire of visual tricks up his sleeve. A video of the activated work revealing its construction can be seen on the artist’s website.

Volker Kuchelmeister, foreground Juxtaposition, 2010, Interactive video installation, background: A dromological vision machine, 2013, Interactive video installation

courtesy the artist

Volker Kuchelmeister, foreground Juxtaposition, 2010, Interactive video installation, background: A dromological vision machine, 2013, Interactive video installation

On the other side of the room, Kuchelmeister’s A dromological vision beckons us in via a dotted white line on the floor. From several metres back the wide image on the wall in front of us appears like an apparently fixed colour field painting. As we approach along the line the image transforms into vaguely recognisable, subtly vibrating shapes before becoming very specifically a snowfield, or on another approach clouds above a grassy plain, a domestic harbour or a street in a country town. These are tracked by a camera moving left or right, creating an interesting intersection of speeds—the left/right of the screen and the forward/back of the interacting viewer—and making a connection with the title’s focus on speed.

As we move forward and back along the line, we choose to linger longest—who knows why—on that alluring halfway mark where definition hovers, where reality begins to transform into abstraction.

Josh Harle

Josh Harle, Bare Island, interactive video installation

courtesy the artist

Josh Harle, Bare Island, interactive video installation

Another kind of interactivity is encountered in Josh Harle’s impressionistic video image of Sydney’s China Town floating on a large screen. Jutting out from just below its centre is a small touch-sensitive screen on which the same image appears in greater detail. With a finger we can change our perspective on the street or focus on aspects of it, drawing lights and a bower of tree branches closer or setting the image on a slow, vertiginous spin. Although a visually appealing work, the proximity of the touch screen to its larger equivalent makes it difficult to focus on the expanded image without stepping back. But when we did, we ‘lost touch.’ Perhaps we missed something.

Chris Henschke

Lightbridge, Chris Henschke, 2013 realtime animation

courtesy the artist

Lightbridge, Chris Henschke, 2013 realtime animation

Chris Henschke’s work in recent years has been greatly inspired by a Synapse residency at Australia’s most powerful light source, The Australian Synchrotron. A YouTube video documents his time there with interviews and footage of the imagery he created, making science into art and offering scientists and technicians striking virtual representations of their work. Small beams of light are prismatically unlocked revealing fantastical, effusive geometries as in the long wall print produced by processing synchrotron ‘light’ using particle accelerator simulation. The result is a long string of dense, complex circles varying in intensity from gold and orange to near white as they increasingly overlap.

The large screen projection Lightbridge yields a sense of being confronted by the outward flow of synchrotron data converted into vivid animation. Lightcurve (infrared arc) in the Synapse show at the Powerhouse Museum is likewise immersive, this time producing the sensation of travelling through a curving tunnel (as in a synchrotron?), the imagery densely, colourfully detailed. Both works are enhanced by quite musical renditions of data and, possibly, synchrotron hum.

A large human-scale photographic image of a cross-section of a section of the CERN synchrotron in Switzerland (which Henschke also visited) is quite disconcerting—its copper piping and flourish of entwining cables and wires evokes nothing less than steam-punk technology.

Stranger still is Machine Study no. 4 comprising 3D print, turntable, video camera, projector, screen, photodiodes, amplifier and speakers. The 3D print—a semi-fragmented circle of clay-like material—a model “derived from particle accelerator assemblies”—sits on the spinning turntable from which light that hits it is converted to screen imagery reminiscent of the synchrotron simulations already experienced but here with a humbler, even homemade sense of presence. The flickering screen image appears to change in intensity, from pale to darker blues and variations in the shapes of the flickering vertical lines emanating from the spinning model. There’s more here than meets the eye.

As we make our way around the gallery we’re peripherally aware of others entering the space and, perhaps in the absence of those illuminating room notes, cursorily viewing interactive works that really reward time taken to appreciate. So many ideas are manifest in an event like ISEA, so much potential to view in haste to make room for the next surprising thing. Sensory overload is one way to counter distraction. On Friday last, new media aficionados, stilled by Ryoji Ikeda’s electrifying Datamatics, subsequently lingered, transfixed on his captivating Test Pattern installation. Innovative works suggest multiple forms of engagement and Point of View offered us more quietly pleasing, sometimes rewardingly strange possibilities.