Memories of buildings and other ghosts

Stephen Jones remembers What Survives

Do walls have ears? What if they could record, process and play back to you what they had been exposed to in earlier years or generations? In What Survives: Sonic Residues in Breathing Buildings, curated by Gail Priest, 3 installations and 2 listening stations explore the memory of sounds embedded in buildings, perhaps through their material impact, perhaps in the echoes of distant events that re-impinge themselves through memory.

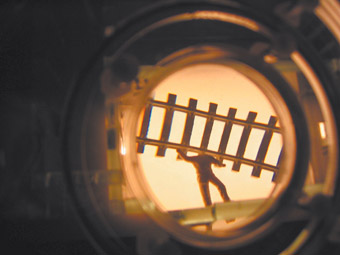

Nigel Helyer, The Naughty Apartment (detail)

Sound occupies the Performance Space as though it were the remains of daylight. The late afternoon when I caught the show led me into a slowly revealed mystery. It seems very odd walking into an exhibition of soundworks where you can’t actually hear anything, but you have to listen and slowly things appear. It’s a show you have to work at; nothing is particularly obvious. Of course the problem with sound art is that the contents of one room can easily disturb the sounds of another. Thus headphones become de rigeur. And, as I rarely read the room notes before I look at a show, I am usually quite unprepared.

Each work deals with memory in some way: Jodi Rose’s memory of spending endless hours “guarding” a bridge; Nigel Helyer’s fragments of tales relating the memory of a mysterious event of momentous psychological power; and Alex Davies’ exploration of memory as the delayed re-presentation of things held in mind (memory), each as installation.

Nigel Helyer’s The Naughty Apartment presents chapters from a tale of mystery by the Russian author Bulgakov, which evoke a moment when a building itself comes alive. Entering the installation, the room is silent, small sculptures sit on plinths in an arc, and a jumble of complex looking tools lie on a table at the back. Walking up to the plinths I notice they all represent the same apartment space, each inhabited by tiny human models in one or other of the rooms, but still no sound, no apparent interaction. On looking at the apparatus on the table I discover that each contains a small induction coil wound around a magnifying glass, some kind of handle and some electronics leading to a headphone so, obviously, I put one on and walk back to the arc of apartments. Now they spring to life. As you peer into each one through the glass, the stories embedded in them are transmitted to your headphones; interludes in the story rising from each model, fragments of a mystery, paragraphs from somewhere in the progress of the tale, but can we ever have the full story? Or do we even need to as we make our own surmises, building on the characters and the behaviour of the cat from The Master and Margarita. The mystery remains, carried from room to room as though the apartment itself had become the gallery space.

In Jodi Rose’s installation, Playing Bridges, a collection of postcards covers the wall and Nick Wishart’s model of a bridge waits in the centre of the room; a single span of cables tensioned from one end via what turn out to be telescopic antennae (the once ubiquitous TV rabbit’s ears). Again, silence. Put the headphones on and … still silence. Having been informed that the bridge is “interactive” I go to touch it and the shrill sounds of a theremin break out, so I play with it for a moment and then try the span cables but they seem to do nothing. I find myself disappointed given that the theremin offers all sorts of possibilities by varying the lengths of the antennae and using its output to release other sounds. It is only with the small screen on the wall that we hear any of Rose’s bridge music. Her other room features an immensely still video of a castle high on a hill overlooking a river with but the merest flicker of change in the pixels arrayed across the projection screen. I come back a little later and the image has hardly moved but I chance to hear a short orchestral manoeuvre, which apparently only appears once in every 3-hours. Is this Rose’s view from the bridge that we are presented with?

Alex Davies’ Sonic Displacements were said to be spread throughout the gallery. Apparently the work gathered sounds of visitors to the gallery some hours before and reprocessed them, playing them back to us as long delayed memories of moments gone before. The paradigm is reminiscent of Davies’ work at Experimenta last year, which used video as well as incidental sound and to bring you face to face with yourself, and invented others, from prior moments in the installation. Sadly, I don’t think this sound only version worked. The main installation room was completely silent each of several times I entered it and the corridor sounds were a mere whisper of people talking in the background, they might simply have been in another room for all I could tell.

Not prone to hanging about in the gents’ toilet I found the Listening Station: Men’s Toilet set of short commissioned playback works disconcerting. On later listening they turned out to be intensely interesting. Sunugan Sivanesan’s The WC Overture, produced from “stealth recordings of toilet blocks” works the sprinkle of men pissing, the rattle of toilet roll fixtures and drains gulping into the elements of a rhythmical reflection on ablution and the sounds of the water closet. In Amanda Stewart’s Sign, imagination brings out the hiss of the gas and the boiling of a jug for tea, rendering the voice into microsound, bubbling up as the phase change starts on the way to boiling, bubbling up out of traces of words, teetering on the verge of pure noise. Like Stewart’s, Garry Bradbury’s two Untitled pieces present short vocal reconstructions, but of an entirely different order. In the first the repetitive frustrations of English domestic life through an old woman’s nagging and attempts to converse. In the second, obsession and a toy piano conspire to take Johnny Cash’s The Ring of Fire apart with devastating effect.

Listening Station: Stairwell provided a rather more comfortable environment. Aaron Hull’s Corroded Memories offers snippets of sound swelling into big rounded orchestral forms sweeping over you and vanishing abruptly; rich expanses of memory underlaid by the echoing roar of machines and the quietness of someone speaking. Somaya Langley’s out | side | in suggests isolation, wintry spaces, an increasingly dense soundscape, the wind, outside; inside, the breathing of the earth and the roar of time in a vast expanse of loneliness. In Radiation 3, Joyce Hinterding’s magic wand, the loop antenna with which she draws sounds from the walls and small extrinsic sounds from space that impinge on the earth, brings that most mundane and unavoidable interference, hum, out from the backdrop of everyday life and gives it an unaccustomed beauty.

I enjoyed the experience—and the mysteries.

What Survives: Sonic Residues in Breathing Buildings, curator Gail Priest, Performance Space, March 25 -April 22

RealTime issue #73 June-July 2006 pg. 36