Liberate media art & animate the gallery

Ian Haig: Lively Objects, ISEA2015

Mummy of Panechates, Son of Hatres, (Egypt 1st – 3rd centuries AD)

photo Lizzie Muller

Mummy of Panechates, Son of Hatres, (Egypt 1st – 3rd centuries AD)

Something that has always irritated me is placing media art works together on the basis that they all plug into an electrical wall socket or are made with a computer. Such a curatorial mode removes media art from the world at large. In addition, events like ISEA (International Symposium of Electronic Art) play to the notion of art and technology as affirmative action belonging to a special fraternity of artists, scientists, curators and academics, but rarely question the default method of displaying media art. Other approaches are clearly needed. Anything that removes these works from the media art exhibition ghetto or the technological trade show/expo vibe that so often accompanies them is a good thing.

One way forward was evident at The Vancouver Art Museum in the exhibition Lively Objects curated by Caroline Langill (OCAD University, Toronto) and Lizzie Muller UNSW Art & Design, Sydney). It was part of this year’s ISEA series of exhibitions but you wouldn’t have known it. Lively Objects clearly embraced ISEA’s ‘disruption’ theme placing works in relation to a network of other physical objects and artefacts and displaying them throughout the permanent collection of the museum. The exhibition deployed the notion of distributed agency and presented new ways of considering objecthood in relation to the digital.

The media arts works spread throughout the museum activated strange and uncanny readings of the collection of objects, figurines, dioramas, display cases and machines, now read too as having agency, hidden lives and meanings beyond their ‘mummified’ stasis. Lively Objects explored that hazy zone of in-between states, of things half seen and encountered and of non-technological objects imbued with a form of animism. Here technology reached into the past to bring the dead back to life.

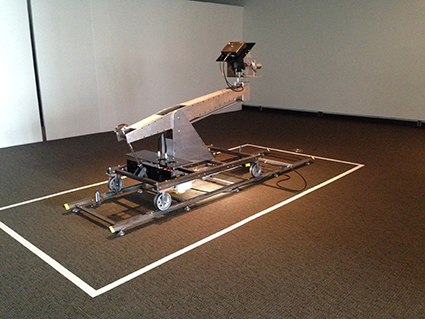

This ‘lively object’ relationship was seen in Simone Jones and Lance Winns’ End of Empire, an oversized robotic projection machine which projects slices of a video inspired by Andy Warhol’s 1964 film Empire, about the Empire State Building. The device never allows us to see the building in its entirety, but only in fragments. As the machine returns from its slow vertical pan to its original position we are left with the disappearance of the iconic building from the skyline. While Warhol’s Empire was an expression of the building as a celebrity, an icon of American capitalism, End of the Empire provides the inverse: the collapse and erasure of the American empire. Positioned next to this work was a mummified Egyptian child in a display case. The weird cognitive dissonance generated between the robotics of End of Empire and this mummified child, yielded a profound and wonderfully disturbing pathos.

End of Empire, Simone Jones and Lance Winn

photo Lizzie Muller

End of Empire, Simone Jones and Lance Winn

Looking like a 19th century instrument, Steve Daniels’ Device for the Elimination of Wonder rolls back and forth along two parallel cables that span the length of a room, taking an assortment of measurements by lowering a mechanical plumb bob and representing this measurement as a grey scale image on a page. The device disrupts the museum collection with a useless process, but also draws attention to the static museum artefacts it seeks to measure. The flickering electronic surface of Norman White’s Splish Splash One, produced as far back as 1974, suggests art and its relationship to technology is not simply born of the computer and animates the museum space with a sense of historical relativity.

Germaine Kohs’ Topographic Table at first appeared like a standard display piece from the museum collection—a table with a topographic, textured surface representing the mountain range north of Vancouver. The table however shook in response to local information concerning seismic activity via its internet connected electronics, resulting in the work suggesting a liveness beyond its initial static appearance.

Lively Objects explores notions of post-disciplinarity in which the connections between objects break down, producing new kinds of relationships and aesthetic resonances. The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles, famed for a being “a museum about museums,” plays a similar game by framing natural history objects (including deliberately questionable ones) with technological devices. Like Lively Objects it sees technology and ‘media’ not as limited to digital ones and zeros but as activating a kind of animism which permeates the physical world.

Museum of Vancouver, Lively Objects, 16 Aug-12 Oct; ISEA2015: Disruption, Vancouver 14-19 Aug

https://museumofvancouver.ca/exhibitions/exhibit/lively-objects

RealTime issue #129 Oct-Nov 2015 pg. 16