Let the body navigate

Kate Richards talks to electronic artist George Khut

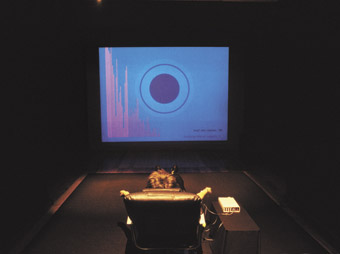

George Khut, Cardio-morphologies (installation)

photo Julia Charles

George Khut, Cardio-morphologies (installation)

George Poonkhin Khut is an electronic media artist whose immersive sound installations have been exhibited in Australia and the UK. The acclaimed video installation, Nightshift, created with dancer Wendy McPhee was exhibited at Arnolfini (Bristol, UK) as part of the Breathing Space exchange program with Performance Space and PICA (see www.georgekhut.com). Khut is presently engaged in post-graduate research at the University of Western Sydney School of Contemporary Art, creating installations using biofeedback–the process of electronically measuring changes within the body and displaying these to the person being observed so they can learn to influence the behaviour being measured. Cardio-morphologies was installed at Performance Space, July 21-Aug 7, 2004.

Khut’s new biofeedback-based work, Drawing Breath, will be shown at Sydney’s Gallery 4A, April 14-May 14. Later this year it will be part of a touring concert program of the same title with The Song Company in a selection of motets, madrigals and contemporary songs, from Ockeghem to Oxygène–and the breathing rhythms of the audience.

Skin

My father came here in the 60s from a Chinese family in Malaya. My mother’s family is Anglo-Celtic Australian, and it was through her that I gained most of my early exposure to contemporary art. [Dad’s] been practicing martial arts since childhood, so there’s been an awareness of mind-body interconnections via the various internal energy and self-cultivation approaches implicit in traditional martial arts techniques.

He was actively practicing this during your childhood?

Yes, and encouraging me to do so as well but I just didn’t have the fighting spirit! I went to Kung Fu classes every week, for many years. It’s only recently that I’ve started to get some glimpse into the significance of some of these techniques. There was also an understanding that meditation and related traditions of self-cultivation were a part of our East Asian cultural heritage and something to be proud of.

Our family culture was essentially atheist, though as time went on, it grew to include an element of ancestor worship. Although my sister and I were both educated in Christian schools, there was an open hostility towards traditional Western mythology–original sin, a God that answers your prayers, going to heaven or hell when you die, or bodily functions being somehow sinful. I think things like this really sowed the seeds for my present interest in how we represent and ‘practice’ our embodiment.

Breath

I moved to Sydney [from Tasmania] in 2001 and intentionally immersed myself in a creative crisis. I thought ‘If I’m going to do this [art practice] it better be worth my time and energy!’ I wanted to work with very basic physical materials, in a very minimal way, being very inspired at the time by artists like Wolfgang Laib and James Turrell. But I was also deeply interested in the suggestive power of electronic sound: trance-like ritual practices and the altered states of consciousness they can induce. I was also reading about fringe media practices like accelerated learning techniques, subliminal advertising and brain-wave biofeedback–the various ‘back door’ approaches to subconscious exploration. Biofeedback interaction seemed to combine both these interests very neatly.

How did you first start playing with biofeedback?

I looked though a listing of biofeedback practitioners in New South Wales and sent out an email to all of them asking for help with learning about biofeedback! Dana Adam of the Active Learning Centre responded and enabled me to try a variety of biofeedback interactions out at her clinic. I had initially proposed working with brainwave biofeedback but it’s hard to get psychologists and psychiatrists to say on record that it’s completely safe without appropriately qualified supervision. They recommended breath and heart rate biofeedback as a safer option, and one that sat well with my interest in more ‘whole of body’ approaches like breath-based meditation. There has already been a lot of art work developed from the 70s up to the present exploring brainwave biofeedback. The idea of breath and heart centred interactions seemed relatively unexplored, and I was interested in the contributions these functions make to our overall experience and self-image.

I realised that with my early work Pillow Songs (RT24, p46) I was very interested in how people respond when they are lying horizontally in a darkened space. Later I learned that just lying down will tend to increase parasympathetic nervous system arousal [our internal rest-relax-regenerate reflex]. I’ve been interested in how various cultural practices intuitively involve this process of parasympathetic arousal. I’m thinking here about devotional practices such as prayer, chanting, meditation and trance-dancing, and the kinds of ritual architectures designed to accommodate these activities–the effect these practices have on your cardio-respiratory state, and the role of these unificatory experiences at a bio-social level.

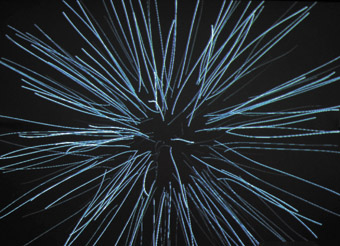

George Khut, Drawing Breath (detail)

What are unificatory experiences?

Experiencing your self as deeply connected to a larger reality, that ‘all of nature speaks to me’ feeling. It’s curious that these sorts of experiences are usually taboo in contemporary arts practice–we tend to annex them off to dance parties, yoga classes or chronic illness treatment programs.

The gist of my doctorate proposal to UWS was “how do you develop multimedia systems that in some way enable people to navigate through their bodily experience?” For me personally it was also a response to the disembodying qualities of a lot of popular virtual reality iconographies–this idea that we will download ourselves into a computer and do away with our bodies forever.

This [biofeedback] technology provides a point of entry into aspects of bodily experience in an age when so much of our body is being left out. I’m exploring some of the functionalities we see in Eastern traditions, in a way that feels authentic to me. Rather than importing some exotic taxonomy for mind-body inquiry and cultivation, could we attempt to develop cultural practices from our own personal and immediate experience of ourselves? Biofeedback is a tool that trains our ability to sense and respond physically to our experience of the world. As an artist, I have to ask ‘how do I connect these sensations and abilities to my existing mix of cultural histories and practices?’ I’ve recently been studying the Feldenkrais Method of sensory-motor education, and it’s had a significant impact on the direction of my work. These kinds of ‘somatic’ methodologies have developed very concrete ways of investigating mind-body organisation and the body, based on lived personal interactions.

Biofeedback enables us to work with categories of experience that aren’t easily accessed by representational or symbolic forms of communication. By consciously eschewing symbolic imagery and representation…artists can foreground the physical presence of the observer. The observer’s perceptual system becomes the figure against the void-like ground of the design of the work.

Immersion

My interest in immersion relates to this process of foregrounding your own perceptual processes–processes that are usually taken for granted. Sure there’s the whole VR tradition where you immerse yourself in a panoramic imaginary landscape/narrative, but personally I’m more interested in the processes taking place inside the participant.

What I find challenging in a work like your Cardio-morphologies is that it takes some degree of training and commitment to move past the interface and achieve the full body immersion.

In terms of the interface design [by John Tonkin], you’re building an instrument and it does require some skill from the user. At the same time, I have been struggling with the idea that these works are instruments that people then express themselves through. I’m much more interested in people learning to listen to the voices of their own bodily experience, which is such a rare event in our culture.

My main expectation would be that the audience give the work some time–half an hour to 40 minutes is ideal. And a big part of what I’m doing in this work is saying there are experiences and forms of understanding that won’t unfold in 5 minutes, and there are forms of understanding and communication which can’t take place in a normal symbolic/language centred context. I want to make the learning phase [for Cardio-morphologies] shorter and let people feel confident to make correlations–which is pretty fundamental to effective biofeedback. It must be clear to the audience ‘oh that’s my heart, and that’s it changing’, and I have to manage that in terms of interface design.

Affect

It’s very pure work in that way–it’s pure affect.

People say ‘why is this art? Why not do it in a yoga studio?’ My response to this is that in presenting this work in an art gallery I’m placing that experience in a context that invites a certain spirit of inquiry and speculation–I hope. My understanding of art is that it provides people with ideas about other ways they can ‘be in the world.’

So your work is purely formalist in that it’s not about content or subject matter?

No not really. I would say that its subject is not a subject that we are used to considering as ‘subject’–that is, ourselves and our own somatic being. And maybe it’s time we started to consider that as a subject. Part of the tradition of our Western mind-body split is the separation of subject from object whereas most contemporary philosophy and psychophysiology refutes this separation. So how do we start to acknowledge that in terms of our cultural practices and representations?

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 31