Identity vs Noise, Lloyd Cole

photo Oliver Toth, Accent Photography

Identity vs Noise, Lloyd Cole

Interactive musical composition and performance have come to epitomise human interaction and social evolution generally. Lloyd Cole’s Identity vs Noise: 1Dn extends an interest in electronic music that he has pursued following his success with the band Lloyd Cole and the Commotions in the 1980s. The work builds on his earlier album 1D: Electronics 2012-2014, the superscript ‘n’ added to indicate an infinite number of possible sonic variations that can be generated within the new work.

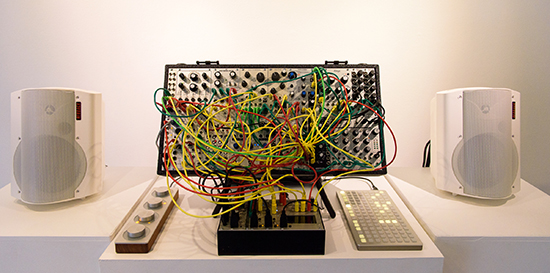

Cole discussed in depth the origins and mechanics of Identity vs Noise: 1Dn with a fascinated audience at the work’s launch at Nexus Arts in Adelaide. His specially designed equipment comprises a modular synthesiser that generates sequences of sounds to form pieces of music, heard through a pair of loudspeakers and transmitted to three other galleries—in Dublin, Tokyo and Helsinki—via a video screen showing a live feed from the Nexus gallery. The sonic raw material, or the ‘identity’ to which the work’s title refers, resembles the sound of an acoustic guitar or electronic keyboard.

Adjacent to the synthesiser is a foot switch labelled “Press” that invites viewers to participate with is a corresponding switch in each of the other three galleries. Pressing it can cause subtle or significant changes to the sound—perhaps a shift of key, of timbre or even from consonance to dissonance. Such interventions constitute the ‘noise.’ If audience members in all four galleries happen to press their switches simultaneously, they will trigger a significant change in sound. If no-one in any of the galleries presses a switch, the sound will still evolve by itself as the synthesiser responds to the sounds it has itself generated—noise is inherent in the compositional design. But while we can influence the sound, we can’t control it and can’t predict what changes will be induced by pressing the switches.

Cole’s synthesiser is capable of a greater range of sound shifts than, for example, a Mini-Moog, and the equipment overall is very attractively presented, establishing a persuasive audio-visual aesthetic in its art gallery setting. This work adds to the tradition of musical composition and performance using synthesisers and Cole pointedly states that he eschews the use of computers to make music.

Lloyd Cole

photo Will Venn

Lloyd Cole

Lloyd Cole was commissioned to produce Identity vs Noise: 1Dn by the Hawke EU Centre for Mobilities, Migrations and Cultural Transformations, a department of the University of South Australia that focuses on the politics and culture of the European Union. The Hawke EU Centre’s website indicates that the Centre “examines migration, asylum and protection issues in an environment where war and conflict, climate events, and global economics are acting as ever-present catalysts for large-scale movements of people.” The intention in commissioning this work was to explore “the interplay of identity and difference.” The interactive, distributed nature of the work is thus a metaphor for human interaction across the globe, interaction that is uncoordinated and whose effects are unpredictable—sometimes harmonious, occasionally chaotic and always evolving.

In his opening remarks, Cole indicated that once he has released a song it becomes, in effect, public property. This principle is extended in Identity vs Noise: 1Dn as viewers partly ‘take over’ the compositional process, and we might see this also as a metaphor for the process of public interaction, where a concept or principle expands and evolves as it circulates, its origins lost. Lloyd Cole and the Hawke EU Centre provide important insights into music, electronic composition, performance and the nature of human interactivity. It’s to be hoped that viewers in all four galleries, rather than seeing this work as a musical novelty, will appreciate how, in experiencing it, their interaction with the world shapes the world itself.

–

Lloyd Cole, Identity vs Noise: 1Dn, Installation hosted by the Hawke EU Centre for Mobilities, Migrations and Cultural Transformations at the University of South Australia.

Nexus Arts, Adelaide, transmitted to TAV Gallery, Tokyo; Trinity Long Room Hub, Dublin; and the Museum of Finnish Architecture, Helsinki; 25 Jan-3 Feb

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017

Casey Jenkins, sMother, Venice Performance Art Week 2016

photo Caterina Ragg

Casey Jenkins, sMother, Venice Performance Art Week 2016

In December 2016 I travelled to Italy to attend the Venice International Performance Art Week. The ambitious event brought together an extraordinary daily program of live works, an exhibition and panels with which to generate dynamic discussion and pedagogical platforms. Held biannually over the past six years, it is an international drawcard for performance art makers, curators, cultural operators and audiences alike, to gather for a week that is as much think tank as aesthetic experience.

2016’s Fragile Body-Material Body concluded a trilogy conceived by German artist duo VestAndPage. The curators are dedicated to representing diversity in cultural practice and to hosting a space where groundbreaking and established artists mix with mid and early career performers in a generous and impartial environment. There is an expectation for all artists to attend the whole of the week-long event. This year, seminal artists Stelarc, Orlan, Franko B, Marcel Antúnez Roca (a founding member of La Fura Dels Baus) and Antonio Manuel (Brazil) gave platform presentations to an absorbed crowd. Each iteration has seen Australian artists bringing new approaches and ideas to the mix. In 2014 Leisa Shelton Fragment 31 came on board as a co-curator and in 2016 presented artists Casey Jenkins, James McAllister and Stelarc alongside the UK artist and In Between Time Festival director Helen Cole.

Casey Jenkins, sMother

The room in which Casey Jenkins quietly performs sMother each day is strangely like a contemporary shrine. The architectural space plays into a reading that resonates with religious signifiers. Flanked by mirrors, Jenkins sits on a small clear plastic faceted stool which mimics cut glass. Behind is a life-size video portrait rendered iconic by its fluorescent light frame. Intentional or not, these quasi-religious references reinforce the artist’s sense of enquiry.

This durational performance is the final in a trilogy exploring how society preserves “absurd gender roles” and reinforces expectations of women perceived to be “of child-bearing age.” Over the week, Jenkins calmly knits a constrictive bind from yarn emerging from the vagina. Woollen knits, often associated with nurture and warmth, here take on a more insidious role, restricting and hobbling the artist’s body as the length of the narrow scarf increases each day. Manual Zabel’s soundscape adds to the sense of menace.

Positioned on either side of the room, resembling altar candles, are two pedestals, each with six red buttons. The audience can choose to activate these and in doing so their devotional action unleashes a volley of recorded public commentary. Patronising, opinionated and judgmental, it serves to remind us how we can all be complicit in the collective controlling of women’s bodies. Jenkins silently and stoically absorbs the relentless psychological barrage in this, the more precarious and disturbing part of the performance. The work’s religious overtones are made more apparent with the inclusion of the particularly oppressive and dogmatic voice of a conservative evangelist. Combining these overt commentaries with subtle activities, Jenkins reminds us that we still have a long way to go if we are to unbind deeply held expectations of the female body.

James McAllister, (utter) Oratorio, Venice Performance Art Week 2016

photo Edward Smith

James McAllister, (utter) Oratorio, Venice Performance Art Week 2016

James McAllister, (utter) Oratorio

In contrast, James McAllister occupies a constructed architectural space in which the performing body is so subtly present as to be almost invisible. Situated in an exhibition space away from the first floor performance galleries, (utter) Oratorio comprises a false wall in which a number of apertures have been inserted: a frosted rectangular window; a perforated masonite slide box; a small display box containing the smoothly contoured, used soap bar; a peep hole; and a letter box. McAllister refers to the functioning of his deceptively understated work as “a strategy for the soft architecture of human transaction.”

On numerous visits to the site, I witnessed subtle changes similar to the shifting landscape of a domestic space: the soap bar had altered; the slide box was open. Once, the small frosted window played host to a shadowy figure. I watched mesmerised as the grey-blue light blurred on contact with the palest skin: a cheek, a lip, an eye-socket, a hand. One moment I felt as if I was looking into an underwater abyss, the next a ghostly threshold. As with sMother there is an offer to actively engage, however in McAllister’s work it comes in the form of exchange. Via the letter-box, visitors post an item and a minute later receive a signed and stamped receipt describing the item delivered, the location, the date and the transaction number. On the final day I returned to this whispering-wall of sorts to find a gallery of tickets, photos, pictures and messages scrawled on postcards, pieces of paper, shopping receipts. The past week had been transformed into an archive of human interaction reaching through a literal and metaphorical barrier in an effort to connect.

Anna Kosarewska, Redirecting through, Venice Performance Art Week, 2016

photo Alexandre Harbaugh

Anna Kosarewska, Redirecting through, Venice Performance Art Week, 2016

Anna Kosarewska, Redirecting through

Barriers and borders manifest in a number of works this year, made more urgent in light of the current global socio-political landscape. Ukrainian artist Anna Kosarewska’s Redirecting through, performed across three days, could be seen as a triptych exploring inheritance, invasion and survival. On the first day, Kosarewska sits on a pedestal, her lap and head covered with a traditional embroidered fabric. Carefully and serenely she picks out a pearl, holds it for a moment and then either drops it or chooses to delicately sew it to the skin of her décolletage. A gas mask hangs ominously on the wall.

On the second day, this composed space is replaced by a more menacing one. Illuminated by the light from a looped geometric video projection, reminiscent of 20th century socialist design, a naked Kosarewska prowls the space to driving, repetitive music. At one point she traverses the room, slowly guiding torches across her body. Reminiscent of searchlights, they take on a sinister tone, seeming to probe deep beyond the barrier of the artist’s skin. References to war are evident in props such as toy soldiers and tanks. Pinned to the walls these cast distorted shadows generated from Kosarewska’s handheld flashlights.

On day three there is a return to a state of repose. Beneath two photographs, a long bolt of light cloth drops from the wall and unravels toward Kosarewska, shrouding her supine body on its low-lying gold podium. A mask of sprouting seeds covers her face and similar seeds are embedded in the cloth close to the wall. Renewal is evident in this image and I can’t help thinking about the opportunity to seed possible futures predicated on the acknowledgment of cultural inheritance and the effects of war. Kosarewska’s journey over the past three days has directed my attention to various states of instability—personal, cultural and national—and I am reminded that we must all take responsibility for the consequences of manufacturing borders across all three.

PREACH R SUN, For Whites Only, Venice Performance Art Week 2016

photo Edward Smith

PREACH R SUN, For Whites Only, Venice Performance Art Week 2016

PREACH R SUN, For Whites Only

This notion is echoed in PREACH R SUN’s performance epic, For Whites Only, which makes explicit the incredibly personal effects of racism accrued when crossing borders and experienced via cultural artefacts. From the moment he crossed from the USA to enter the EU the artist donned an orange boiler suit with the work’s title printed on the back. Once in Venice he was manacled to a cinder block which constantly accompanied him until his performance on the sixth night of the festival. Evoking a black evangelical preacher, he challenged and harangued the audience, repeating, “White Guilt, Black Shame.”

Welcoming us to the “auction block,” PREACH R SUN painted his dark skin to an extreme black, asking us if he was beautiful. As he cried out to Jesus for salvation, we watched with him cut-up porn movies eroticising black males in submissive roles to white males. Tensions rose notably when a woman in the audience intervened by taking hold of the staple gun the artist was using to affix fake money to his body. He responded by exclaiming that the work was real and not a performance and that no intervention could save him.

At the work’s penultimate point, working with images of a crucified and sacrificial black man, he implored us to acknowledge his humanity by repeating the words: “I am a man!” At first defiant, this repetition moved from anger to plain statement and concluded in a heartrending supplication. At the end, a visibly emotional PREACH R SUN deftly shifted the mood, asking who would share his burden. One by one, audience members passed the cinder block out of the space, down the stairs and into the courtyard, where it was smashed. A symbolic action heavily charged with the intensity of the last 90 minutes, it served as a potent reminder of how we must take steps to change the ways we unconsciously reinforce privilege and racism.

Over 50 artists performed across the eight days of Performance Art Week. It is impossible to convey the high calibre, dedication, depth of inquiry and generosity of each. There is more I would like to write about: the panels, the exhibition rooms; the late night artist dinners; but for now, know that we laughed, we cried, we squirmed and we were entranced. But most of all we celebrated a brilliant and diverse international community.

–

The Venice International Performance Art Week, 10–17 Dec 2016

The Venice International Performance Art Week and VestAndPage publish limited edition post-event hard cover catalogues documenting the exhibition and live performances, with essays on performance art-related issues by international scholars. 2012 and 2014 editions are now available. They include documentation of performances by Australian artists Jill Orr, Barbara Campbell, Sarah-Jane Norman and Julie Vulcan.

Julie Vulcan is a Sydney-based artist and writer best known for her durational performance works (Squidsolo, RIMA; Drift). In 2014 she performed at the Venice International Performance Art Week and attended the 2016 iteration as a writer and respondent with the support of the Australia Council for the Arts.

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017

1967: Music in the Key of Yes concert, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Prudence Upton

1967: Music in the Key of Yes concert, Sydney Festival 2017

Five concerts revealed the strength of the 2017 Sydney Festival programming of unusual concepts, forms and instruments. This was music-making of high order for welcoming audiences.

1967: Music in the Key of Yes

In the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall, Yirrmal Marika opened and closed this superb concert (which will be repeated at the Adelaide Festival) with a fine sense of ceremony. His remarkable vocal skills (performing largely in language), didjeridu playing and dance (birdlike to Emily Warrumara’s account of the Beatles’ “Blackbird”) evoked a vast cultural history in dialogue with powerful popular songs in an event focused on celebrating a crucial political event, the 1967 Referendum that recognised Aboriginal peoples as Australian citizens.

On two large upstage screens, archival film deftly unfolded an impressionistic narrative from across the 20th century, featuring images of traditional Aboriginal pride, assimilation, destitution, protest, and the speeches (notably from Faith Bandler) and polling booths of 1967. Brief interviews with the public at that time revealed support, condescension, prejudice and hostility. Oddly missing from the footage were images of the beauty of country so fundamental to Aboriginal life.

The singers—Yirrmal Marika, Emily Warrumara, Leah Flannagan, Dan Sultan, Adalita, Radical Son, Thelma Plum, Alice Sky, Ursula Yovich—and a wonderful supporting ensemble led by Neil Murray drew on a wealth of Australian songs. “My Island Home,” Archie Roach’s “Took the Children Away,” Warumpi Band’s “Blackfella/Whitefella” and Yothu Yindi’s “Treaty” were heard alongside Goanna’s “Solid Rock,” Midnight Oil’s “Dead Heart” and American classics such as Sam Cooke’s “Change is Gonna Come” (a powerful rendition from Radical Son), Nina Simone’s “Feelin’ Good” (Thelma Plum in a beautifully restrained account) and Patti Smith’s “People Have the Power.” Among other pleasures was Dan Sultan’s affecting “The Drover,” about Gurindji man Vincent Lingiari, the stockman who became a leading land rights activist.

With its songs passionately performed, subtly arranged and juxtaposed with historical film and an intriguing projected text by novelist Alexis Wright, 1967: Music in the Key of Yes generated an embracing sense of community between singers and audience. A rousing ensemble encore rendition of the Beatles’ “With a Little Help from My Friends” was followed by a sense of return to ceremony in a gentle transition from “Blackbird” into Yirrmal Marika’s performance of Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu’s “Wukun,” a song about storm clouds (Wuku) which are images of the songwriter’s mother’s people, the Gälpu.

Ellen Fullman, Theresa Wong, Long String Instrument, Sydney Festival 2017

photo by Kjeldo

Ellen Fullman, Theresa Wong, Long String Instrument, Sydney Festival 2017

Ellen Fullman Long String Instrument

Eyes closed, ears wide open, I’m swathed in the complex hum and buzz of Ellen Fullman’s 25-metre-long string instrument which the artist plays as she walks the great length of its resonating wires, holding them pinched between her fingers. The aural halo conjures string orchestras, sitars and electronic droning (the device is acoustic but its resonating boxes are miked), music rendered more complex by Theresa Wong’s cello layering of slow, deep riffing and digitally treated high carolling. Eyes open, it’s performance art: the slightly built Furman first moves slowly backwards for much of the length of her instrument, close enough for me to hear the soft click of her white-soled black sneakers, then all the way forwards and then, in shorter forays, in both directions, pausing only to apply rosin to her fingers or set a small motorised wheel spinning to generate a drone passage. Definitely a show for those into sheer reverie and the musical unusual. I ached for a post-show demonstration of the instrument’s capacities. Which, in a way, was what Chris Abrahams offered in the show’s opener on the Town Hall’s magnificent organ, unleashing its highest and lowest notes—the latter unearthing a rumbling, mechanical beast—and, in between, playing passages of delicately considered counterpointing and soaring organ romance.

Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Jamie Williams

Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires, Sydney Festival 2017

Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires

After experiencing Montreal composer Gabriel Dharmoo’s Anthropologies Imaginaires, I was buzzing and twitching with a profound sense of the pre-verbal, pre-instrumental music of tribal peoples as played by this virtuosic artist via complex vocalisations, physical self-manipulation and movement, subtle and rough.

Having just enjoyed the Denis Villeneuve film The Arrival, in which a linguist (Amy Adams) attempts to communicate with giant heptapod aliens, and reading Ross Gibson’s 26 Views of a Starburst World (UWA Press, 2012) about the 1790s encounter between English surveyor William Dawes and 14-year-old Patyegarang (read in order to better appreciate the festival’s attention to local language), I attended Anthropologies Imaginaires eager to appreciate a composer’s account of ancient music-making across cultural and temporal barriers. I was in for a surprise.

What I encounter is a lean, dark-haired young man in black T-shirt and trousers who never speaks but performs a series of non-verbal utterances, tuneful and otherwise, each introduced by onscreen cultural experts who identify and comment on the tribes who made these proto-musics. The vocal elaboration and gesturing is convincing, commencing with a wordless prayer with wafting notes, clicks, falsetto and allied hand glides. As the performance proceeds, the cultures the artist evokes grow stranger, though the techniques—yodelling, overtone singing, vibrato-induced chest thumping and rasping growling make sense—but in this case all from one tribe? Then there are screen cutaways to a making-of-documentary in which the ‘experts’—whose commentaries are beginning to sound weird—are revealed to be stage hands. A demonstration of the music of “Third-Sex Children,” delivered from a low, wide-legged stance and in long-note falsetto and mask-like face-making evokes Chinese opera but perhaps also ancient Indian dance in which one performer plays multiple roles.

“Weborgez,” is a 12-tone music culture in which music is literally presented as child’s play. Irony and parody have clearly entered the frame. An exorcism for “male sexual guilt” in another tribe is executed by vocalising into a bowl of water, drinking and expelling the liquid as if vomiting, violently wrenched from the stomach, and then self-flagellating after cleaning up the mess. The audience giggles. Any sense of reality has long exited. But even so, the “Aquatic Songs” sequence, with water kissed, puffed into, sucked and voiced with a pulsing falsetto, seems plausible.

We are gently cajoled into becoming a trance choir so that, as an onscreen specialist derisively puts it, the leader can “solo purely egotistically.” One tribe is condemned for its failure to drill and mine—the mumbling performer looks lost. In contrast, a “hit song” follows—jazzy, pop and “world,”—its culture celebrated for having survived via cultural absorption (akin, of course, to mining). Finally, the specialists are revealed for what they are: casual surmisers, ideologues, a Minister of Assimilation and a promoter of wine and golf tours. Our shared culpability in desecrating cultures we don’t understand has been deeply sounded in Anthropologies Imaginaires with the tools of musical expertise, deployed with wit, vocal grace and dextrous physical performance.

Einojuhani Rautavaara

photo Sakari Viika

Einojuhani Rautavaara

Sydney Symphony Orchestra, Rautavaara

Things that fly. Birds. Angels. Spirit. Mine did in the Sydney Festival’s Rautavaara concert, lifted by superb performances of the composer’s distinctive blending of impressionistic world-making and soaring neo-Romantic melodising. Einojuhani Rautavaara died on 27 July, 2016. This tribute event offered a scandalously rare opportunity to hear his work in an Australian concert hall, in this case one with an ideal acoustic, warm and responsive to the tiniest details in orchestration and the recording of the bracing calls of huge flocks of swans commencing migration from Finland’s north.

Cantus Arcticus, Concerto for Birds and Orchestra (1972) features birdcall taped near the Arctic Circle in marshland and bogs awash with birdlife. It opens with an entrancing, warbling flute duet (beautifully acquitted) which is then joined by woodwinds, together anticipating the arrival of the birds and a corresponding swelling cello-led melody. The subsequent shifting dynamic (sensitively captured by conductor Benjamin Northey) between orchestra, individual birds and flocks (the calls sometimes pitch-adjusted by Rautuvaara) achieves a glorious synthesis of avian and human music-making, above all in the work’s glorious third and final movement, the swan migration, transcending the fleeting suspicion that you’re listening to the score from a nature documentary. A trumpet soaring above the fullness of the score’s unsentimental sense of triumphant nature suggests the flock rising to leave while flute and woodwinds carroll indefatigably, as they did in the first movement, at one with the swans. Softly descending harp notes signal departure within seconds. Silence. Although heard many times on CD, this live performance breathed new life into my appreciation of Rautavaara’s sublime entwining of birdsong and the music we ‘sing’ through our instrumental prostheses.

The intensely dramatic 11-minute Isle of Bliss (1995) also evokes birds if not so literally, its inspiration Finnish dramatist Aleksis Kivi’s “Home of the Birds,” a poem seeking repose, possibly the calm of death. After opening forcefully with a rising sense of urgency—woodblocks rattling and flutes piping, bird-like—calm briefly ensues until recurrent deep string orchestral strummings introduce a return to the opening melody, now yearning and soaring. It is twice interpolated with ‘birdcalls,’ which towards the work’s end become incessant chatter beneath the emotional turbulence and then, on their own, dive into a sweet tumbling of notes and, wonderfully, a final lone, gliding two-note call, so distinctly birdlike. Northey and the orchestra have delivered us and the poet, with care and passion, to the Isle of Bliss.

With larger instrumental forces, Symphony No. 7 Angel of Light (1994) evokes the power and sense of transcendence associated with angels but also their role as intermediaries between god and humans. French horns and brass rise above full-bodied, sometimes keening, sometimes soaring strings in another of Rautavaara’s surging constructions—here underlined with strummed harp—and their descents into thoughtful, meandering reflection. Angels here are reassuring, the movement ending in calm. The second movement’s series of three powerful trumpet calls, from two slightly different pitched instruments—followed by brief bursts of fearsome percussion, conjures alarming angels, although their last fading appearance, undeniably bird-like (and wonderfully played), softens the angst. As does the dream-like third movement, a reverie ending with soft, repeated warblings behind the string and horn musings. The brass fanfare opening the final movement is followed by emphatic carrolling from woodwinds and strings—akin in the density of movement to Canticus Arcticus—underscoring soaring brass. In the ensuing softening, we see the trumpets muted but finally no less powerful in the work’s climax, simply more integrated, bringing human and angel together. Rautavaara didn’t aim to write a programmatic work, but the kinship of birds, angels and spirit were evident in the concert’s admirably selected three works and superbly conducted by Benjamin Northey with the balance of restraint and release necessary to realise Rautavaara’s vision.

AAO with Nicole Lizée (top R), Sex, Lynch & Video Games, Sydney Festival 2017

photo Prudence Upton

AAO with Nicole Lizée (top R), Sex, Lynch & Video Games, Sydney Festival 2017

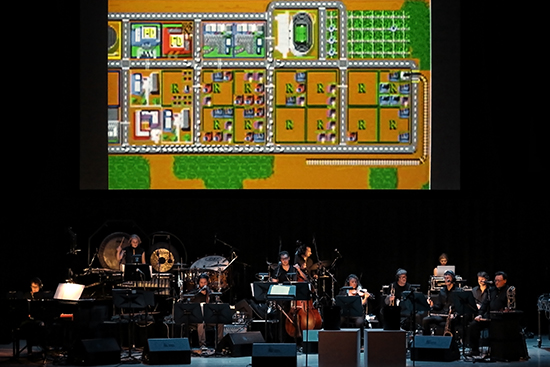

Nicole Lizée, Sex, Lynch and Video Games

Nicole Lizée with the Australian Art Orchestra, Sex, Lynch and Video Games was another festival highlight, an exciting and fruitful pairing of Canadians (Lizée, pianist Eve Egoyan and guitarist Steve Raegele) and Australians (AAO, led by Peter Knight).

Lizée ‘s David Lynch Etudes (she’s also tackled Hitchcock) are played by Egoyan to projected and radically edited clips from David Lynch films. The outcome is funny, alarming and aesthetically satisfying in the fusion of playing that yields rippling waves, dark intoning, astonishing stuttering and grand romantic pianism with revealing investigations of very short film moments. My favourite was of Naomi Watts as Betty in Mulholland Drive (2001) surprised by the sudden appearance of Laura Harring as Rita. Lizee cuts and repeatedly stutters the film so that it becomes an intense, sustained portrait of Betty saying “You came back” in quickfire states of happiness, shock, fear, suspicion and hatred as the piano shuffles darkly. Watts is perfect for such dissection and elaboration. As are Nicholas Cage and Laura Dern in Wild at Heart (1990) elsewhere. At one point, Egoyan leans to the side and plays slide guitar as well as piano as a guitar is played in Twin Peaks onscreen. Motifs emerge that appear in this and other excerpts in the program: images totally flaring or sparkling, a brush appearing and painting in, for example, tears, small photos of characters (and Lynch) placed on a tongue, and an obsessive preoccupation with seemingly incidental details like the window that the camera tilts towards and away from Watts. I’m not sure what they add up to but they lend the works an intriguing totality. What is impressive is not only the dynamic between live piano and edited visual imagery but the cut-up sound of the film made musical in itself and in tandem with the keyboard.

In B-Bit Urbex, Lizée, now upstage with the orchestra at her computer, plays with malfunctioning early computer games, with a keen focus on their “pixelated cities.” The simple, often stuttering images and freezes are aurally textured with complex music that has to responsively slow, compulsively repeat or hover. Band members clap in time, two trumpeters play into buckets of water, there’s a wild big band passage and some fine gentle guitar work, pitched against the image of a plodding game robot. The unpredictability of these old games yields rich musical rewards.

Gian Slater, Tristram Williams, Sex, Lynch & Video Games

photo Prudence Upton

Gian Slater, Tristram Williams, Sex, Lynch & Video Games

After a turntabalism improvisation between Lizée and Sydney’s Martin Ng, which, though fascinating in part, warranted more duration to be revealing, the concert concluded thrillingly with Karappo Orestutura (literally “empty orchestra”) in which a singer adjusts her performance to a malfunctioning karaoke machine (as played by the Australian Art Orchestra). Gian Slater, in superb voice, stays ‘in tune with’ the warped pitches, grinding glides and relentless repeats, maintaining, as Lizée requests, “composure.” Things begin well enough, songs complemented by old footage of couples kissing, fighting, crying, hugging and images of fire. Then a screen explosion anticipates a world about to go wonky, which it does with Devo breaking up on screen and the singer seamlessly executing fractured vocals for “Whip It.” Unexpected images pop-up: the joint-sharing scene from Easy Rider, the dead mother in Psycho, as if the imagined machine has locked onto some other platform. The climax is spectacular: Diana Ross and Lionel Richie onscreen in aged video gazing lovingly at each other, microphones in hand for “Endless Love,” their voices finely realised by Slater and conductor Tristram Williams riding with aplomb every tape stutter, enforced glide and mad looping. The Australian Art Orchestra and Slater, along with a very busy Vanessa Tomlinson on percussion, rise to this demanding occasion with precision and gusto.

Nicole Lizée makes impressive new music—and new audiovisual experiences—from the manipulation, decay and malfunctioning of old technologies. In this concert, the challenging melding of music and media reached a deeply satisfying apotheosis.

You will find music and video works by Nicole Lizée on her website.

–

Sydney Festival 2017: 1967: Music in the Key of Yes, Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House. 17 Jan; Ellen Fullman Long String Instrument, Sydney Town Hall, 13, 14 Jan; Gabriel Dharmoo, Anthropologies Imaginaires, Seymour Centre, 9-15 Jan; Rautavaara, City Recital Centre, 11 Jan; Nicole Lizée, Sex, Lynch and Video Games, City Recital Centre, Sydney, 19 Jan

RealTime issue #137 Feb-March 2017