Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

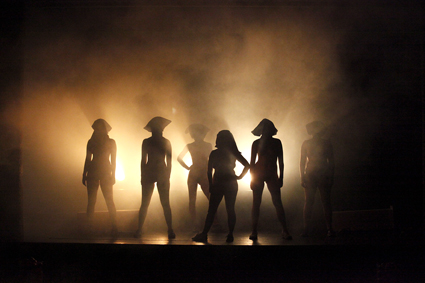

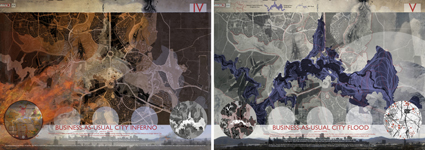

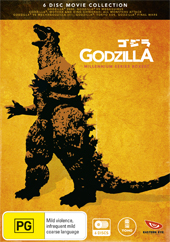

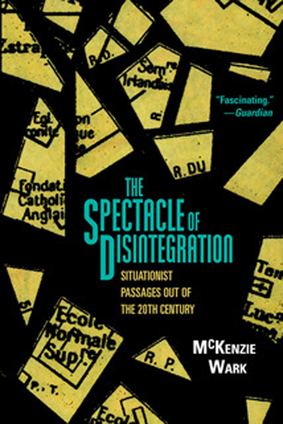

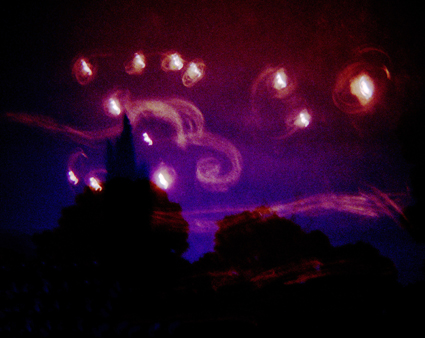

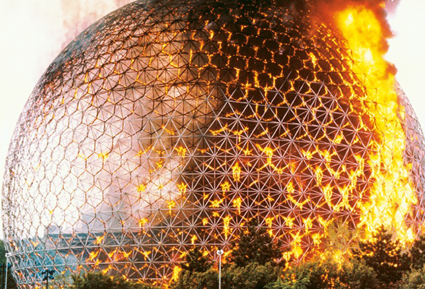

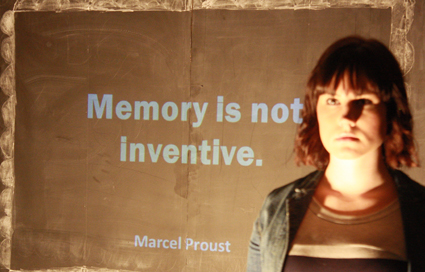

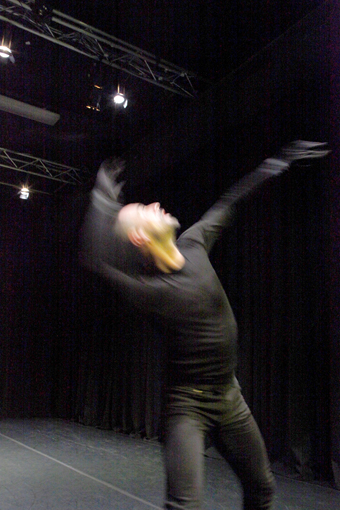

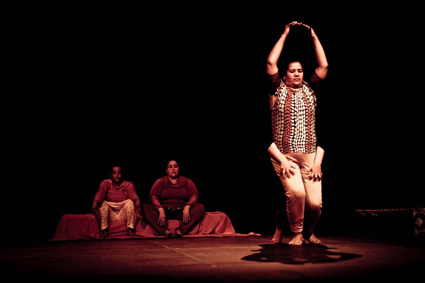

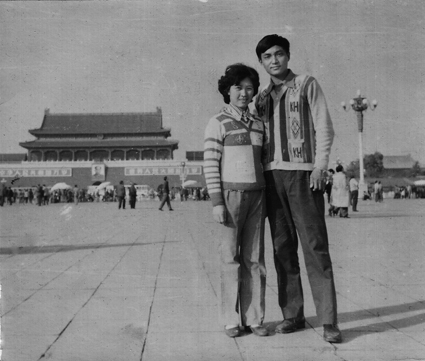

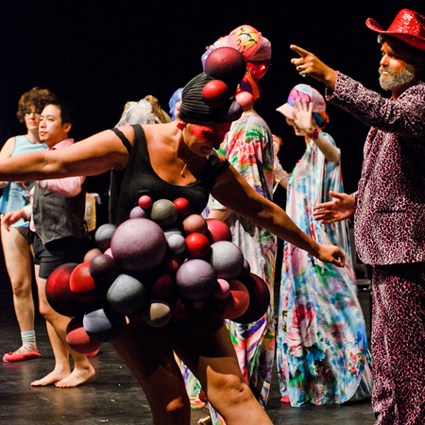

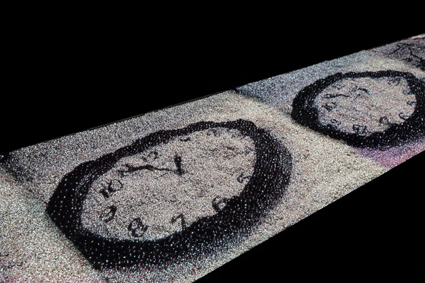

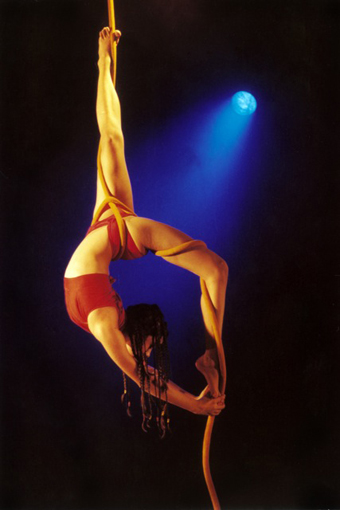

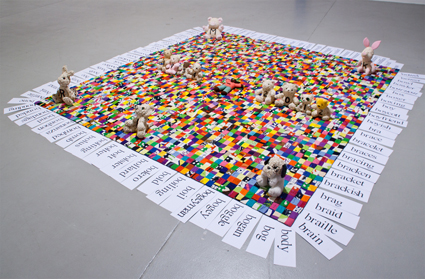

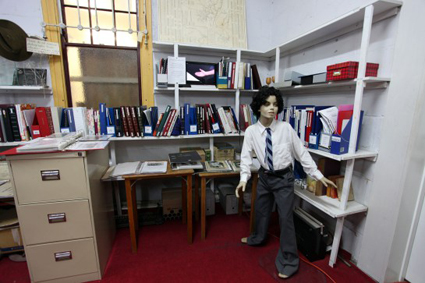

Clark Beaumont, Coexisting, 2013, performed by the artists and commissioned by Kaldor Public Art Projects for Kaldor Art Project 27: 13 Rooms

photo Jamie North/Kaldor Public Art Projects

Clark Beaumont, Coexisting, 2013, performed by the artists and commissioned by Kaldor Public Art Projects for Kaldor Art Project 27: 13 Rooms

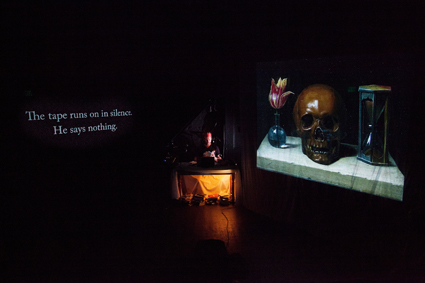

The title foregrounds space. As Klaus Biesenbach says in the catalogue introduction, not 13 Performances nor 13 Artists, but 13 Rooms and later, when talking about developing the project with Hans Ulrich Obrist, of wandering amongst the sculptures in the Villa Borghese, “we could do a sculpture gallery, one room after the other, but in each room it would be a ‘living sculpture’…” (catalogue).

Obrist takes up the curatorial narrative of wanting the exhibition to occupy time as well as space. So, with terms borrowed both from the visual and performing arts, what conceptions of space and time did 13 Rooms give us?

Sydney-siders like to go to the water to recreate. The wharves and piers closest to the CBD are a story of continuous erasure: in place of canoes, cruise liners; in place of bond stores, Biennales; the site of a bitter waterfront dispute will soon be a casino. The artists of 13 Rooms were not asked to address the history or material properties of Pier 2/3. The space for their work had been determined well before it landed in Sydney, in Manchester as 11 Rooms and in Essen as 12 Rooms. For the Sydney iteration Harry Seidler and Associates—the firm renowned for modernist architecture in Australia—was commissioned to design variations of the classic white cube gallery, one for each artist. Outside the cubes, the audience performed: promenading, catching up, queuing, standing back to watch, chasing after children (or not) and choosing when to effect the next entrance.

As for the selection of artists, most are big names on the international art circuit, though not all derived their reputation from within the field of performance (Hirst and Baldessari, for example, famously extend definitions of painting). The importation of name artists to Sydney is not new—the John Kaldor projects since 1969 and the Sydney Biennales since 1973 provide a lineage of exposure to local audiences of ambitious works from elsewhere. Among the local art community such encounters stir a genuine willingness to engage which, if not well managed, can quickly slide into cynicism or resentment. The Sydney Biennale curators were made to recognise this early on and have included a (usually) good proportion of Australian artists in their selection, thus elevating those artists specifically and the local scene generally to the international stage, and as a side benefit, allowing for natural dialogue to arise between locals and visitors.

The 13 Rooms curators had commissioned works that specifically did not rely on the presence of the artist-authors. ‘Sculpture’ (transportable, transposable, mute) as per Biesenbach’s narrative, was still then the stronger term. The ‘living’ part, it was inferred, could be achieved by alienating certain qualities or qualifications (appearance or physical training, for example) from the subject. For those of us coming out of a whole other history and ethos of performance that embraced the risks of authoring-while-doing, unrepeatability and an assumed contract between performer and audience of doing time together, it was a difficult proposition to swallow.

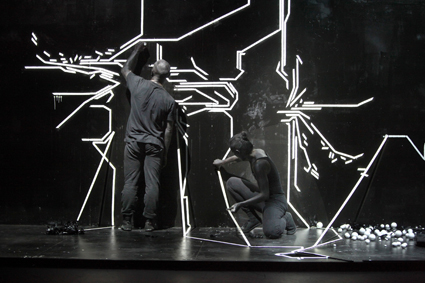

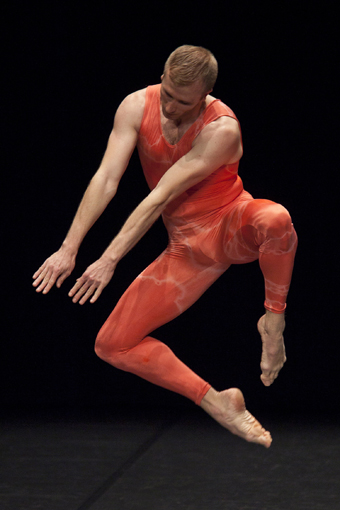

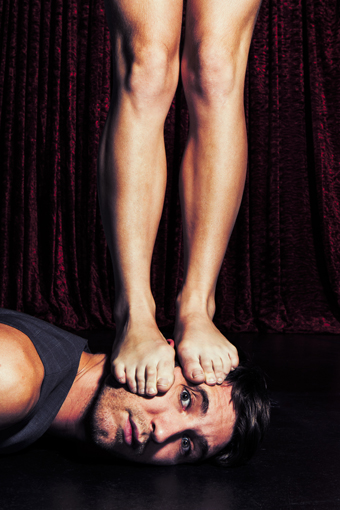

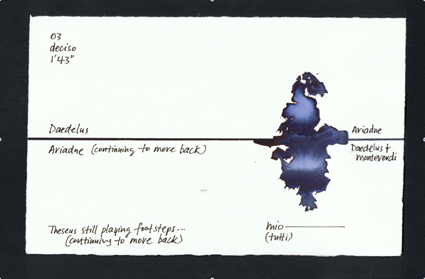

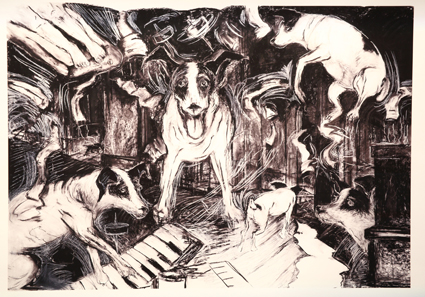

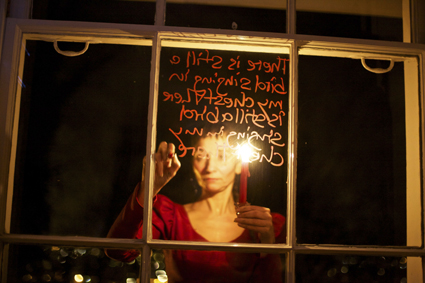

Of the international works, some came off better than others, depending on the performance strategy applied. Santiago Sierra, for instance, delegated the idea of authenticity to other bodies. His Veterans of the Wars of Afghanistan, Timor-Leste, Iraq and Vietnam Facing the Corner, brutally rejected any thought of entertainment (no movement, no eye-contact) and threw the complexities of moral responsibility back on the observers. Hirst and Ondák leant heavily on and were rewarded by the skilled sociability of their ‘interpreters’ to deliver their work. Delegation of bodily presence over time was more problematic for the two artists who were the inhabitants of their work when originally performed: Marina Abramovi?’s Luminosity of 1997 and Joan Jonas’ Mirror Check of 1970. Both works suffered from their management (warnings, guards, taped off areas, ‘no camera’ signs, constant opening and closing of doors and half-hour shifts for the ‘interpreters’). That the performers were able to hold focus and thus transmit a real sense of live engagement says much for their experience as practitioners in their own right.

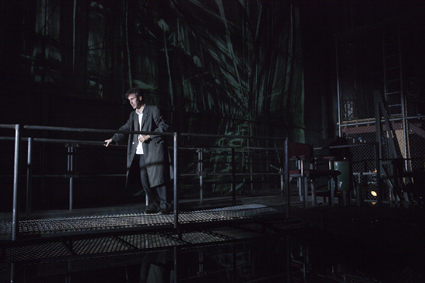

Interestingly it was the locals—young Brisbane-based duo Clark Beaumont—who relied on endurance and improvisation for the effectiveness of their work. They were the only authors as performers and the only artists willing to take the 7.5 hours per day opening times (that is, gallery time) as the given duration for their performance. They could not have fulfilled the ‘living sculpture’ brief more closely.

As ephemeral as the works they briefly housed, the 13 Rooms are gone now. Pier 2/3 is still there, waiting to receive its next guests.

Kaldor Public Art Projects, 13 Rooms, curators Hans Ulrich Obrist, Klaus Biesenbach, 11-21 April, Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney. Quotations from Hans Ulrich Obrist & Klaus Biesenbach, “Curators in Conversation,” 13 Rooms catalogue, Rushcutters Bay: Kaldor Public Art Projects, 2013.

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg.

© Barbara Campbell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Marina Abramovic, Luminosity, 1997, re-performed for Kaldor Public Art Project 27: 13 Rooms

photo Jamie North/Kaldor Public Art Projects

Marina Abramovic, Luminosity, 1997, re-performed for Kaldor Public Art Project 27: 13 Rooms

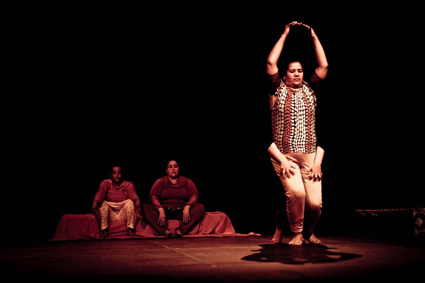

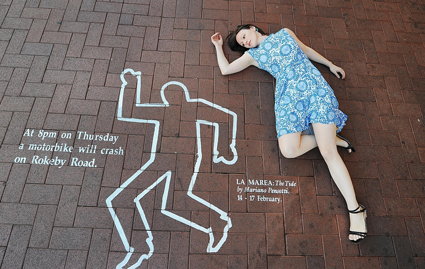

Sydney dancer Nalina Wait was one of a group of nine performers in 13 Rooms whose task it was to re-perform Joan Jonas’ Mirror Check (1970) and Marina Abramovi?’s Luminosity (1997) at half hourly intervals and alternating between works (plus breaks). In Mirror Check the performer slowly inspects her naked body with a hand mirror. In Luminosity, the naked performer is positioned high up against a wall, arms and legs extended while supported by a bicycle seat.

Wait spoke with Clare Grant, Lecturer in the School of the Arts and Media, UNSW, and her students about the experience. Here are excerpts from Wait’s responses to questions.

Eye contact

We were given the general task to look at the audience: “keep still, move slowly and look at the audience”…But when you actually do that—when you actually lock eyes with someone who doesn’t know you…possibly thinking of you in a kind of objectified way—[there is a sort] of exchange, of seeing each other. It was really quite profound. You’d see people who’d get really upset, freak out and wouldn’t really want be looked at and they’d hide, but couldn’t help but have a little peek. And eventually they’d somehow open up and, ‘Okay, I’ll look back at you.’ And we’d actually meet and that was really quite amazing.

The task

The task was the same [as in dancing]. In dancing, in improvising, normally I’ll develop a task or my body will…or there will be something that I’m doing that is a task that I must do…So in many ways it was just like dancing except mostly just using the eye [which] was the biggest movement. And I got really tired because I tried as much as I could to focus on the people I was looking at and not have a generalised or softened peripheral gaze.

I think about it as a job. The task is to look. I’m constantly thinking about the looking, the engagement of the looking—noticing and refreshing looking, being alive to the looking all the time, not getting tired of it or bored with it, to refresh it and to notice it in every moment.

Being naked

To begin with we took turns in front of each other. The scariest moment was the first time, taking your coat off and standing up there. But after a while we got used to it with each other. Then we extended the length of time we were doing it for, to negotiate how to do that over time, what kind of things you need to do in yourself to maintain that and build up to it…[W]hen the public actually came in…they were so open and taken by [the work]. I realised I didn’t need to push them or hold them in their place with my gaze. I could actually be more receptive and compassionate and more active in it, communicate within it rather than hold them back and defend myself. But it took a bit of time to come to that. I only realised I was doing that after one guy left and he said, “That chick was fully eye-balling me” or something…I thought, oh yes, I’ve got to also receive through the eye a little bit more.

Agency

[The gaze] is where I had agency. Other than that I felt much like I might if I was in a dance piece in which the choreography was exactly set and I had no room to really interpret..It was more restricted than I’ve ever [been]. I did as much as I could [with my eyes] because I felt that was where I was.

Vulnerability

If there was the occasional person trying to undermine the performance I just thought about being Jesus…(LAUGHS), being compassionate towards them. This is your situation…it’s not actually mine. [I was] trying to be compassionate with them having an issue with it inside themselves, inside the work. Because it is confronting work.

Focus

For me, in Mirror Check there was even less agency [than in Luminosity]. I tried to squeeze as much agency as I could from it …or interest. I think that’s what the work is, finding interest in the task. And after the thousandth time of looking at your own reflection in the mirror, it is boring. It really is. But if there is some way that you can focus—I had to do it through focus mostly. I just had to literally see every little thing and be engaged with it in the scene for me to feel like I was doing the work. And I noticed if I ever just slightly shifted my vision, or went out of focus, the atmosphere of the room would break and people would leave. You feel like you’re doing this quite personal thing, but people feel it.

Mirror Check was tricky for me because I prefer to be able to see the people in the room and feel we’re all in there together rather than…keeping a fourth wall in a performative sense and not looking at anyone, which I found difficult. I had to look…even if it was at the wall or somebody’s shirt so I could still feel engaged.

So I felt slightly disconnected from the audience but then again I’d finish a round and someone would applaud. So it’s like, okay, you’re with me. Then I’d just listen more to the tone of the room, to feel whether people were with me. That’s when I noticed if I went out of focus, it would break.

Kaldor Public Art Projects, 13 Rooms, curators Hans Ulrich Obrist, Klaus Biesenbach, 11-21 April, Pier 2/3, Walsh Bay, Sydney

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 8

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

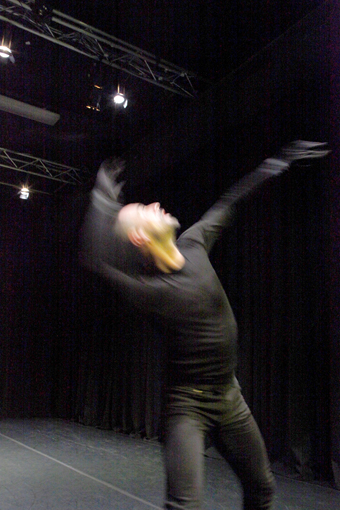

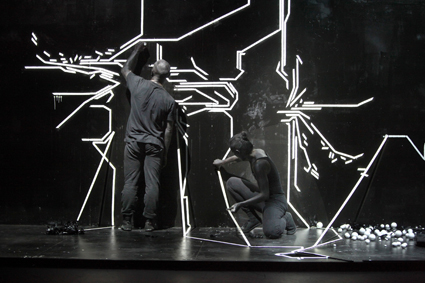

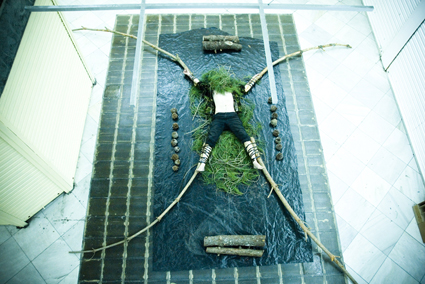

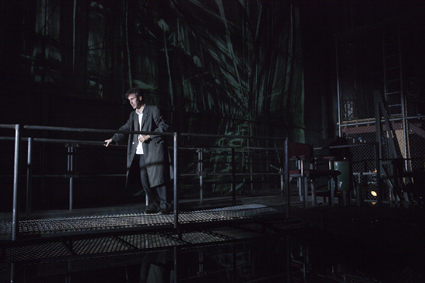

Jamie Lewis Hadley, Analogue to a Blunt Trauma, Spill Festival London

photo Guido Mencari

Jamie Lewis Hadley, Analogue to a Blunt Trauma, Spill Festival London

In the 2013 SPILL Festival of Performance, I witnessed three artists presenting diverse interpretations of personal and public desire using raw, essential and intimate body fluids.

Jamie Lewis Hadley, Analogue to a Blunt Trauma

Waiting at the far end of a cavernous white warehouse space feels like being on a film set. There are lights and cameras anticipating action and a white sheet-covered couch framed by a corridor of pillars. At the far end a door opens, a man enters and emerging in silhouette he walks purposefully down the centre of the room with what seems to be a gun in his hand. As he passes each pillar, fluorescent tubes blink on. This beginning of Jamie Lewis Hadley’s performance is an intentional set up, referencing cinema tropes and creating an expectation of theatrical artifice. However, from here we witness a more intimate yet perfunctory act, as collaborator Dr Belinda Fenty proficiently extracts and fills a medical grade blood bag with Hadley’s blood.

The casual demeanor with which Hadley lies across the couch and the friendly exchanges between the two belie the more serious nature of the act. I think of blood and loss, this reflection amplified by the subsequent proceeding violent act, in which Hadley takes aim and shoots the hanging blood bag multiple times. Real gun, real membrane and a rapid release of real blood; the metaphor is not lost. The moment is shortly echoed on a blood-stained sheet that had been dragged across the floor and hitched as a screen. Here the action is replayed in high definition slow motion. The effect is at once jolting and seductive. Jamie Lewis Hadley’s work is provocative and intelligent, its precise delivery relies on blurring boundaries while challenging the politics behind consumption of shocking, ‘beautiful’ trauma.

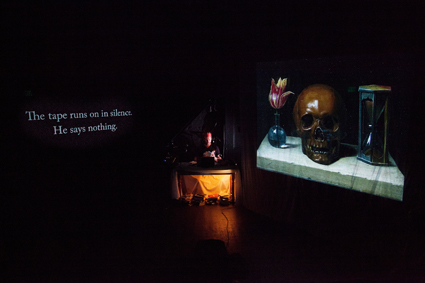

Julia Bardsley, Medea_Dark/Room

Julia Bardsley, Medea_Dark/Room, Spill Festival, London

photo Pari Naderi

Julia Bardsley, Medea_Dark/Room, Spill Festival, London

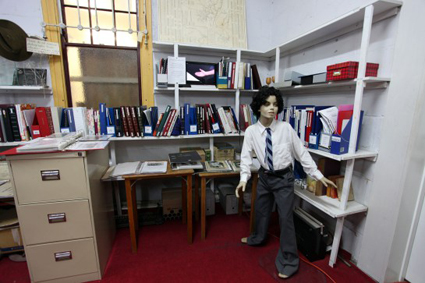

From the moment I ‘enter’ through folding red and cream latex, I understand something is developing in here and it’s sticky, magnetic, electric and gold. I am reminded of entering the folds of the domestic heater to find the minute liminal world inhabited by the radiator lady on her stage in Lynch’s Eraserhead. There is a stage of sorts in Medea’s room, which she inhabits intermittently to conduct her ‘glorious genitalia’ experiments. On one visit I witness one such moment. Medea stands in front of a wall piece, one of the many expertly considered installation elements that make up her darkroom. Referencing theories of the relationship between sex and the gaze, this metaphorical mirror contains seven round sculptural elements that signify a journey from arousal to sublime bliss—the centrepiece literally bursts out of its frame like a red multi-pronged fleshy sea creature. Medea selects a frame and enters her ‘stage,’ defined by a projection. The image is striking, she has become the personification of one of her many detailed scientific constructions and formulaic scribblings. Wired up from nipples to groin, each breast protrudes from Medea’s fetish-styled garment. She pulses electrically, literally etching out orgasmic potential onto the carbon canvas of her genital frame. There is an exquisite seductiveness to Julia Bardsley’s loaded and intricately layered performance installation. Regardless of the point at which I encounter her experiments, I witness the vital moment of creative combustion; whether it is the small detail in the eclectic workstation amid liquid drenched gold sheep and a magnetised prophylactic or a pulsating Medea in a circle of light.

Martin O’Brien, Last(ing)

Martin O’Brien, Last(ing), Spill Festival London

photo Guido Mencari

Martin O’Brien, Last(ing), Spill Festival London

The room smells of chemicals but I wonder if this is conjured by the sight of a radioactive green substance that fills various buckets placed around the edges, where we the audience hug the walls. Martin O’Brien lies ceremoniously on a table as David, his assistant, ritually applies gold leaf to his chest. This delicate act, of marking out a pair of golden lungs, is broken by O’Brien intermittently coughing up mucous into a glass beaker. It is at this moment that the other elements in the room feel more menacing and foreboding.

I am aware that O’Brien’s practice revolves around “physical endurance and hardship” informed by his chronic cystic fibrosis. What follows is a series of procedures and tasks that not only serve as metaphorical illustrations of symptoms but also convey a sense of a body objectified within a medical regime. The artist’s work is unforgiving, messy and raw, never pretending to be otherwise. Within moments of fragility there is strength. I am held by the final action, reflecting the journey of a body purged. Martin stands encased in a prison of barbed wire, his head covered in a lung shaped latex hood. The green fluid into which he had previously plunged forms clumps on his body hair. As I witness the labour of his breathing and excruciating gasps for air, one thing shines through—the remnants of his golden lungs, a defiant signal of the artist’s reclamation of his body.

SPILL Festival of Performance 2013, producer Pacitti Company, London, 3-14 April; spillfestival.com/

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 10

© Julie Vulcan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

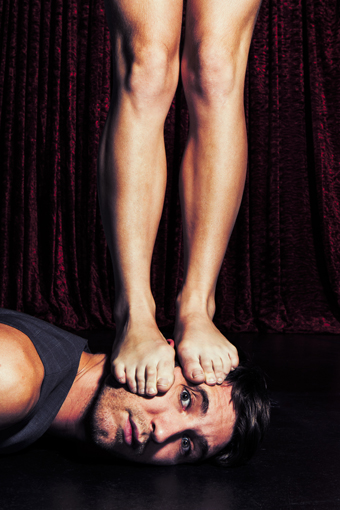

Walking: Holding, Rosana Cade

photo Rosie Healey

Walking: Holding, Rosana Cade

Pacitti Company’s SPILL Festival is two weeks of sensorial encounter where the personal, political and mythological are transferred through the bodies of performers and audience. Sixteen of the 25 works are by women. The following three shots glide from wide, mid to hand-held, close-ups of the gendered, queer world we live in. If this opening has a certain eau de pussy, it’s an invitation to read on, not necessarily a warning.

Lauren Barri Holstein, Splat!

Splat! is the sound of 100 tomato juice filled balloons thrown and burst on a knife’s edge clutched by The Famous Lauren Barri Holstein’s vagina (insert handle first if you want to try this at home). It’s the sound of douche and douche again all over the chest and mouth of someone you care about. Give me a towel.

It’s a deconstructed post-fairytale in a forest inhabited by zombie Woodland Friends, where Bambi, canal birthed in a condom placenta, trophy mounted, rollerskates blindly through emissions, urinates near the vomit, near the target, on twins and hangs as a slaughtered carcass stuffing a burger in her cake hole. It’s a feminine schlock technical rehearsal on a closed Hollywood set with The Famous calling her own stage cues and requesting repeats. It’s a tower of cliché, ideology, genres and dispassionate delivery that might make you choke, with laughter.

You are shunted from wince to cringe to clenched sphincter then leant towards a performance precipice and asked with a hand held mike, “How do you feel emotionally, right now?” She has to go harder because you can’t feel it anymore. Do it again.

Splat! straddles porn, gets bulimic at the microphone, cleans and sticks the unstickable with tape. Its frame has a weft that might muddle your expectations of the next brown-eyed money shot—the sluiced mountain of images is planted with tender instructions, sensitive ballet pointe ballads, the full, uncensored, itemised budget for the show and the soft silence of long blonde hair clippings snowing gently down. Put that back together.

It’s a vulnerability fuck-over and The Famous Lauren Barri Holstein is in control.

Lucy Hutson, If You Want Bigger Yorkshire Puddings…

Lucy Hutson is the kind of cooking companion who makes her own personal recipe. In If You Want Bigger Yorkshire Puddings You Need a Bigger Tin she mixes sexual politics with a family focus group, body identity and a biography of gendered experiments into a disarming dish served as a dialogue between documentary video and contemporary performance, with the lights on.

In an era where queer women debate the actual choice made by younger women in transition, rather than the right to choose, Lucy Hutson offers a home-made brand of good old fashioned asexual identity that is delightful and refreshing.

In the same way you can make a food comparison by asking if your grandmother would recognise it, Lucy approaches gender transition by preparing to run it past the ladies at the Women’s Institute. No snips and no tucks, just a ball of wool, a roll of cling wrap, a shot of self-acceptance and the courage to live with fuzzy edges. The Women’s Institute would be proud.

Rosana Cade, Walking: Holding

I dare to keep my eyes closed on a busy London road and anticipate each swirl of density coming towards me as the moment Walking: Holding will begin. Rosana Cade’s delicate, cold fingers take mine for a walking story of same sex, mixed ethnicity, fag hag and other couples.

Cade and her serial strollers lead us through personal experiences to the point where self-consciousness can invade intimacy and hands meeting below the hip divide.

Rosana’s stroll takes us to an ironwork sign, “LADIES.” I walk with a young, cross-dressed man in a sweet floral blouse, flats and a touch of lippy, down a small dirty street where big men manhandle large tools. I’m released between a van and a tag wall where anticipation and ankles tip awkwardly on a pile of rubble. It’s funny how many loaded frames there are in nondescript locations. I hold the hand of a man whose story makes me clutch it. I stop breathing. This is close. We recover when he asks for, and I offer, something of my own that raises his eyebrows. We part at a sheened wall where the close reflection of our coded couple is joined to make three before it becomes a new two.

These walks take you past public displays of affection, and more: from the throwaway indulgence for heterosexual, Caucasian-matched, western couples, to the erosive emotional fallout of hand division for others and intimacy rarely touched between strangers.

Do you think we make a happy couple on these strange streets?

SPILL Festival of Performance 2013, producer Pacitti Company, London, 3-14 April

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 11

© Cat Jones; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

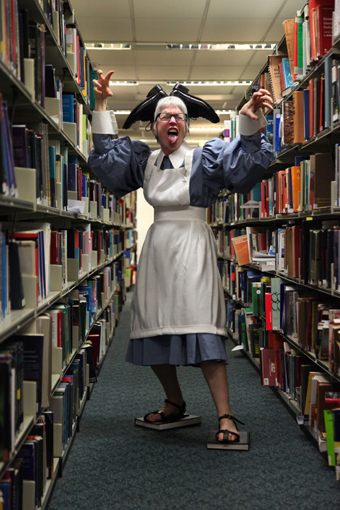

Selina Thompson, Pat it and prick it and mark it with b, SPILL Festival of Performance 2013

photo Pari Naderi

Selina Thompson, Pat it and prick it and mark it with b, SPILL Festival of Performance 2013

In the morning I am told Quizoola, Forced Entertainment’s iconic 24-hour question and answer performance, is sold out and despite their best efforts, the wonderful people at SPILL and at the Barbican have not been able to find a spare ticket.

I watch a little of it live online and in that 15 minutes a conversation takes place between Robin Arthur and Terry O’Connor in which he asks, “Would you like me to touch you?” She answers, “I wouldn’t mind if you touched me.” “But would you like me to touch you?” “I’m not saying I want you to touch me, but I wouldn’t mind if you touched me.” The audience laughs in the theatre far away.

Selina Thompson, Pat it and prick it…

SPILL National Platform takes place in a series of studios over three floors and the place is abuzz with activity. In Selina Thompson’s Pat it and prick it and mark it with b, in a room on the ground floor the artist is making a dress out of cake. Soul music plays on an iPod and the smell of cake fills the air. People are invited to help, cakes come out of the oven, are layered on to a cake rack and stuck together with jam and pink icing. It’s a performance that makes itself. Delightfully unselfconscious, the artist and her best friend and helper walk about, baking and working in their underwear, singing a bit and talking casually with the audience who seem to become Thompson’s friends in the process. On the walk upstairs, from one performance to the next, “on contact” is scrawled on the walls, evoking the theme of the festival with marker pens and paper.

Julie Vulcan, I Stand In

Julie Vulcan, I Stand In, SPILL Festival of Performance 2013

photo Pari Naderi

Julie Vulcan, I Stand In, SPILL Festival of Performance 2013

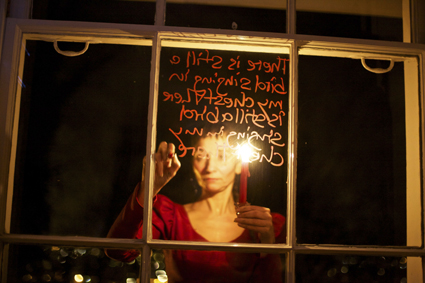

Entering Australian artist Julie Vulcan’s I Stand In, the first hit to my senses is a warm, gentle balm for the brain—the smell of healing oils. Vulcan stands at the other end of the room in front of a wood panelled wall with an altar of white flowers to one side and a body, beneath a white cloth, laid out before her on a table. The backdrop suggests a Hawaiian funeral parlour. The ritual begins with the removal of the cloth. The body is firmly massaged for 15 minutes. The artist cradles the heavy, limp body in order to oil the back. It is possible to imagine it is not breathing.

The most striking thing about witnessing this eight-hour performance is that each touch on the participant’s body creates a haptic connection with my own, each part responds as though the touch is happening directly on my own arm, my cheek. I realise that my body, more than my mind, is witness, responding before I think. In its generosity to the bodies of both the participants and the audience, I Stand In reminds us of the care we can enact towards each another. It reminds us of the strangers’ hands that guide us from our mothers’ wombs, that nurse us when we are sick and the hands that care for us in death. It reminds us that we are all part of the cycle of care, that our bodies recognise before the mind has time to catch up.

Heather Cassils, Becoming an image

On entering Heather Cassils’ Becoming an image on the lower floor of the building we are held in a black ingress so, we are told, our eyes can adjust to complete darkness. In low light the audience sits on the floor around a grey mound.

Sounds come first, a hiss, phut, huh; those of a fighter warming up. They get louder, stronger and then violent as fists hit something solid. Like a shock delivered straight into the brain, the image is there of a body, small and strong, flung against the mound of clay.

Photographer Manual Vason is Cassils’ performance partner in the work in which the only light is the flash of his camera. We see Cassils punching the clay, working to break down the mound. The fight is intimate, sexual, the smell of sweat adding another sensory layer. The performance takes place mostly in the afterburn on the retina, as in the darkness we try to catch up with the shock contact of light on the surface of our eyes, the image of the artist’s body leaving traces of negative images. In the gaps in our vision it is possible to make out the shape of something bigger that is alluded to in this performance, a summary of what we miss in the darkness, the invisible fights against the monumentalism of history. In the words of Heather Cassils, “You have to break things down to build things up.”

SPILL Festival of Performance 2013, producer Pacitti Company, London, 3-14 April; spillfestival.com/

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 12

© Madeleine Hodge; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Image: Coney, A Small Town Anywhere, BAC Scratch 2012

photo Matt Howey Nunn

Image: Coney, A Small Town Anywhere, BAC Scratch 2012

In 2009 the Battersea Arts Centre in London hosted A Small Town Anywhere, a new work by UK-based company Coney. In it around 30 participants took on the role of villagers in a small country town. Each concealed a terrible secret and likewise had a mortal enemy among the other villagers.

A Small Town Anywhere condensed an entire week of drama into the space of roughly two hours; days and nights passed with subtle shifts in lighting; paper snow fell at one point and gossip, treachery and paranoia threatened to tear the little community apart.

Tom Bowtell and Tassos Stevens, two of the company’s co-directors, describe Coney as mixing “live and digital art forms to create immersive stories and play.” Their work, as well as the work of other groups such as Hide and Seek, Slingshot, Splash and Ripple and The Larks, is part of an emerging practice that, for ease of reference, I’ll call New Games. Their work varies widely encompassing Tiny Games, a series of 99 “easy to play” site-specific games designed for the streets of London by Hide and Seek, and 2.8 Hours Later, a city-wide zombie chase game, by Slingshot.

In recent years around the globe there has been an increased interest in play. In America campus games of Killer have turned into a worldwide nerf war (based on foam-based toy weaponry. Eds), with Humans vs Zombies. Real World Alternate Reality Games have been produced as marketing tools for Hollywood blockbusters such as Why So Serious? (for The Dark Knight, 2008) and The Beast (for Spielberg’s AI, as far back as 2001). In America there has also been a renewed interest in physical games: street sports mapping classic board game patterns onto the grid of New York streets in PacManhatten and festivals such as Come Out and Play. At the same time, across the UK and Europe, festivals of new games and playful experiences have spread including IGFEST, Play Publik and w00t.

New Games shares territory with the immersive work of English companies such as Shunt and Punchdrunk, in which audiences are free to explore a theatricalised space in order to discover hidden performance and narrative elements placed throughout. Earlier precedents can be found in interactive video art, such as Nightwalks and Frozen Palaces by Forced Entertainment, and technology enhanced Live Art such as Blast Theory’s A Machine to See With, Uncle Roy All Around You, Rider Spoke and Can You See Me Now (all of which utilise various levels of bespoke digital technology to enable audience/player agency within constructed social and performative events.) This is not to suggest a directly causative relationship but to demonstrate the emergence of a common theme in contemporary theatre and Live Art that is shared by contemporary play; participation, immersion and reactivity.

New Games blur the lines between technology, social interaction, location and story. What they have in common is the placement of the participant at the centre of the experience. In most cases, the convergence of specific rule sets, designed environments, narrative elements and participant agency (or some combination of these) generates a shared social experience. These experiences are designed to position participants within an abstracted system of organised performance relying on person to person interactions in the physical world to generate emergent narratives.

Alex Fleetwood, director of Hide and Seek, describes A Small Town Anywhere as “a vitally important step in the development of participatory dramaturgy.” Andrezj Lukowski, reviewing for Time Out UK, describes the experience as “an interrogation of ideology and its poisonous effect on community” and notes that “the fraught final stages feel as complex and electrifying as any actor-based drama. The moral decisions we are asked to make might seem simplistic to a fly on the wall, but the luxury of such detachment is long gone.”

Coney, A Small Town Anywhere, BAC, 2009

photo Bryony Campbell

Coney, A Small Town Anywhere, BAC, 2009

In a work like Coney’s A Small Town Anywhere everyone in the room is playing (or is at least aware that a play state is in existence) and governs themselves accordingly. Participants are performing and not performing at the same time. As Guardian reviewer Lynette Gardner describes her experience of the production, “By the time I turn up for the show, I have written my own backstory, which includes a grim secret about (a) murdered baby. The show doesn’t require any acting skills, and, because there is no audience in a traditional sense, all social anxiety about being on show or not doing the right thing quickly evaporates. I play it as if it’s real—and that’s exactly how it feels. For two hours, I lose myself in the show.”

In an interview in 2012, Coney’s Co-director Tassos Stevens explains to me that, “In some ways, Coney’s work is more about giving present audiences the space to play than it is ‘making play,’ certainly that more than ‘making games.’ The essential commonality between all the very different kinds of things Coney makes is the focus on the playing audience experience. Small Town is a framework that we create, which audiences fill in with their play. It’s about the group, the Town, the roomful of mostly strangers and everything about the group mind. It’s also about the web of individual narratives that players make for themselves, and how those interplay and a set of external challenges that change the stakes and the game (if they are paying attention). It’s about a community under pressure and what happens between a roomful of mostly strangers playing.”

Since 2009 Coney has built on the work of A Small Town Anywhere with the creation of Early Days (of a Better Nation) in which “the audience become part of a Small Country that can be anything it wants to be.” Early Days is the concept of Annette Mees, developed in response to the events of the Arab Spring, Occupy, Anonymous as well as the London Riots.

Play-tested in various locations from Stoke Newington International Airport to the Battersea Arts Centre, Coney describes Early Days as containing “elements of constitution, economic cuts, an assassination, a leadership election, an economy of beans and a live news channel.” The playtests so far have involved seven performers including “one noble leader, two clerks representing the governing machine, (and) three media reporters who were streamed live to a 24hr news broadcast in the room.”

In one way or another, New Games such as A Small Town Anywhere and Early Days (of a Better Nation) are systemic engagements designed to give shape to lived experience. They allow for and respond to player agency within constructed narrative environments. They give participants the chance to practise ‘ways of being’ in ‘not for real spaces.’

Coney, A Small Town Anywhere, Battersea Arts Centre, August 2009; Early Days (of a Better Nation), ongoing development from 2012

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 13

© Robert Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Skye Gellmann, Blindscape, Next Wave Festival 2012

photo Sarah Walker

Skye Gellmann, Blindscape, Next Wave Festival 2012

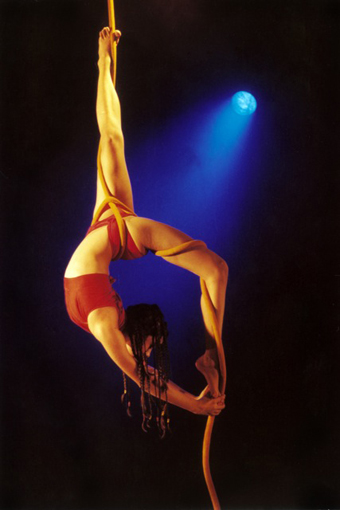

Contemporary circus is a wonderfully open form. It harnesses a multitude of approaches that stem from the notion of ‘Circus’ as the central informing principle. There continues, however, a prevailing opinion that circus skills should only be harnessed for performance when they reflect a narrative/contextual intent—that the display of circus skills, in and of themselves, is somehow gratuitous.

It seems to me that underlying this attitude is a belief that circus as an artform is somehow second rate unless it is woven into another, more worthy, artform such as text-based theatre or contemporary dance.

While I am in no way arguing against the use of circus in conjunction with other elements—text, movement, narrative, or character—I would like to make an argument for the acceptance of circus in its own right.

Over the last year I have seen a series of new works from emerging companies that demonstrate the unique role circus skills play within a performance text. In these pieces, circus skills are used variously as metaphors, character traits, moments of narrative exposition, key elements of mise en scène, heightened atmospheric moments or avenues for creating tension, suspense, surprise, shock or as ways to skew reality and challenge conventional perspectives. At the same time, the acrobatic bodies are used as sites to explore gender, sexuality and race. These works also consider the possibility of circus as pure spectacle, as part of the interplay between form and content.

Skye Gellmann, Blindscape

Skye Gellmann’s Blindscape can be reduced to two main elements: audience members individually navigating the open space through narration and sound effects from an iPhone; and two performers pushing the boundaries of their physicality, as individuals, with each other and with the audience.

Pure spectacle arrives as an element when the artists perform feats of extreme acrobatics on the black circus pole which is the visual centrepiece of the work. The question for me at this point, is what is the iterative effect of this moment? We, as audience members, expect this piece to include circus, and have been watching a series of body movements leading up to this point. Yet until now, all of the physicality could arguably be described as heightened, realistic, dramatic expression. Is there a moment where the work stops being contextual, and presents a moment of pure spectacle? Or has the gradual build-up of dramatic body movements ensured that this moment is just another in the fabric of exploration found in this piece?

Melissa Reeves, The Lost Act

With The Lost Act, playwright Melissa Reeves has created a unique script which utilises a kind of vaudevillian realism, much along the same lines as the literary genre of Magic Realism. In this work-in-progress (directed by Suzie Dee) Reeves collapses the naturalistic world of her characters with that of a vaudeville show. Throughout, the relationships between performers in a circus act completely mirror the relationships in the dramatic narrative. The plot revolves around a young set of siblings in search of their lost parents, who once performed an infamous circus act. At the same time, the siblings are themselves seeking to create their own new act, or, perhaps, recreate that of their parents. Within this plot, Reeves explores notions of identity in a post-colonial world. It is a world in which nothing is quite what it seems, and reality itself is a performance.

Once again, like Blindscape, The Lost Act allows for the possibility of spectacle for its own sake, with a number of scenes that present pure circus skills. However, these are more than mere divertissements, as they are an integral part of the world that is being made. It would be interesting to see how this interplay between naturalism and vaudeville evolves in a full-scale production, so I hope this show reaches the next round of development.

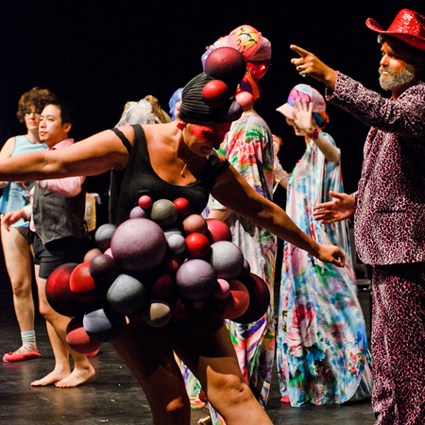

Polytoxic, The Rat Trap

Polytoxic, The Rat Trap

photo Stills by Hill

Polytoxic, The Rat Trap

Queensland company Polytoxic’s The Rat Trap is, on one level, about pure display from go to whoa. It tells the tale of Siamese twins, separated at birth and reunited in a Tiki bar where burlesque acts are indistinguishable from the extraordinary lives of the artists who inhabit them. The show has powerful themes, yet the pleasure, skill and showiness of the circus sweeps around these, giving us a sense of being at some kind of fabulous cabaret, rather than at a serious piece of theatre. At the same time, because the characters are performers in a Tiki Bar, the circus skills are to some extent, though not completely, motivated actions within the narrative. I would call the circus in this context a kind of “Nietschean excess”—the circus is representing that which is beyond definition, or limitation. It is not hiding the narrative, it is exploding from it! If The Lost Act is vaudevillian realism, The Rat Trap is burlesque hyper-realism.

Rat Trap’s vignettes evoke fantastical ideas, but the physical exploits within them are real. This show totally up-ends the idea of reality, and inspires audience members to question the very notions of place, presence and identity, all the while convincing us that we are in an escapist dream. Pure spectacle is the essence and the trump card of this show.

Sara Pheasant, Leggings are not Pants

In Leggings are not Pants, Sara Pheasant, directing performers from the Women’s Circus in Melbourne at 45 Downstairs and Gasworks Circus Showdown, deftly uses circus to heighten themes of gender, sexuality and, ironically for circus, the mundanity of everyday life. For example, a group of women watching television perform a chorus of naturalistic movements which build to become spectacular acrobatic tricks. This allows the skills to be interwoven in the piece, and yet emerge in key moments of strong spectacle. These function much like music in a film. They heighten the audience response to each scene, and occasionally provide an extended exploration of its emotional heart.

Casus, Knee Deep

Company Casus, Knee Deep

photo courtesy the artists

Company Casus, Knee Deep

Knee Deep, by Casus, is a unique work, inspired to some extent by the work of Circa, in that it combines highly athletic circus with a pared back aesthetic. Casus does, however, bring something new to the table. Over the course of the piece we see distinctiveness and quirkiness emerging from each of the cast members. This is mostly achieved through exploring each performer’s relationship with a raw egg. As a framing device, the egg also reminds us of the fragility of life and creates a striking juxtaposition with the strength of the circus performers. This show has a light touch, and invites us into the world it creates, yet, at times, as with many of the pieces discussed, often opens up moments for the celebration of pure circus acumen. Individual acts climax with great skills that seek, and receive, applause. In the context of this show, these spectacular moments are triumphs over the fragility of human existence.

These works demonstrate that circus, even when it is presented, arguably, as skill for its own sake, is always doing more. Circus is much more than a trope or a narrative device. It is a complex ‘body of representation’ which resonates uniquely in each work.

Circus artists/creators seek to use circus skills in performance for myriad reasons: to harness a populist form; to develop a craft they have been honing for years; to use circus as a history of representation from which to draw images, metaphors, characters; to work with an artform that offers freedom from linear, text-based, narrative-driven theatre; and, ideally, freedom from the gendered and cultural stereotypes of dominant discourse.

Ultimately, circus-based theatre makers draw from all of these inspirations to create their work. First, and foremost, they select circus skills ipso facto, for their own sake. Circus is the form from which all else follows.

Blindscape, PACT, Sydney, 19-29 June and touring throughout 2013; The Lost Act, presented as a rehearsed reading in 2012, is scheduled for development in 2013-14; The Rat Trap premiered in 2012, with further seasons in 2013; Knee Deep is touring internationally this year.

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 14-15

© Antonella Casella; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

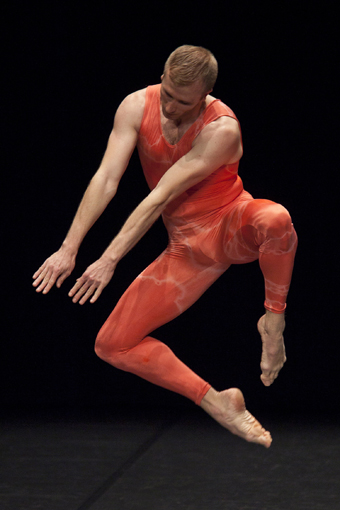

Yvonne Rainer, Sara Wookey, Trio A, UC Irvine

photo Scott Kliger

Yvonne Rainer, Sara Wookey, Trio A, UC Irvine

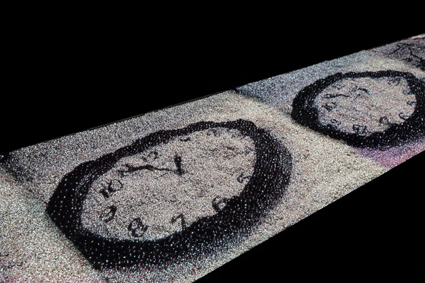

The measured toe-tapping, the headshaking hand-flapping. Sara Wookey is performing Yvonne Rainer’s landmark mid-sixties dance Trio A. Compared to clockwork more than once. Trio A keeps on going steadily, evenly, and never repeats. Its movement vocabulary—stepping, swaying, bending, rolling over—looks a lot like everyday movement.

Artist Sara Wookey is one of five people vested by Rainer—certified, Wookey says—to perform and teach the four-and-a-half-minute Trio A. Re-engaging with Trio A is timely: the Judson Dance Theater’s 50th anniversary was celebrated this past year, and the question of re-performances of 1960s-70s works remains topical. Wookey was in Australia during April at Rainer’s request to speak on Trio A and run workshops in Perth, Sydney and Melbourne through New York City’s biennial Performa program. Wookey’s latest work, Disappearing Acts & Resurfacing Subjects: Concerns of (a) Dance Artist(s), considers the fragility of body memory against fixed representations, and she has initiated reDANCE, which revisits Judson-era dance: projects highly congenial to Trio A.

In Sydney, Wookey explains that it took Rainer six months to make the work. Learning it is challenging, because even the gaze is choreographed—though it is intended that even non-dancers could do it. The body is held as if you’re not thinking about it, just walking to the corner shop or doing something like opening a door or sitting down. Trio A and Judson Dance have considerably influenced contemporary practices internationally, including Australian dance and performance art. Walking, falling, carrying people like objects; no music; non-narrative breaks; and, most surely, a concern with unadorned movement—all of these came from the Judson dancers’ rejection of the priorities and perceived excesses of ballet and modern dance.

When Wookey asked Rainer what ‘certified’ might mean, Rainer unhesitatingly said it was about transmission—like a radio transmitter, Wookey adds. Her performance of Trio A is as precise as that implies. And she gets the attitude right, simultaneously conveying intense focus—Rainer was known in the 1960s for her performance persona, just as she was known for her explicit wish to be a straightforward ‘doer,’ sans glamour or star quality—and Trio A’s matter-of-fact, workmanlike feel.

In her lecture-performance, Wookey demos Trio A straight, and then as an ‘unplugged’ version, uttering Rainer’s aptly descriptive teaching cues as she performs each movement: at one point, arms hang ‘like rocks on strings.’ In Judson style, words can be equivalent to actions: for a handstand, Rainer might now just say ‘handstand.’ The third version of Trio A that Wookey performs in Sydney is set to music, the Chambers Brothers’ In the Midnight Hour. Wookey manages her timing perfectly: both dance and music wrap up at the same moment. This version, presented in exactly the same way by Wookey, now suggests, with deadpan irony, the funkiness of 60s popular culture.

Wookey succeeded in ‘transmitting’ Trio A as a crystalline lens, itself an object of brilliant clarity, and one whose focus is as sharp as ever.

Sara Wookey is the Artistic Director of Wookey Works Studio: www.sarawookey.com; www.redanceproject.org. Sara Wookey, “Dance is Hard to See: Capturing and Transmitting Movement through Language, Media and Muscle Memory,” 13 April, workshop 9-12 April, Io Myers Studio, University of New South Wales, hosted by Performance Space, Sydney

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 15

© Meredith Morse; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

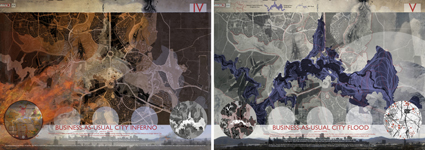

Sedimentary City Canberra by Brit Andresen and Mara Francis, Urban Innovations Collaborative, CAPITheticAL Design Competition

photo courtesy Canberra 100

Sedimentary City Canberra by Brit Andresen and Mara Francis, Urban Innovations Collaborative, CAPITheticAL Design Competition

“My feeling is that the program in print and online is always a mere blueprint and you really rely on the people to take it up. It’s like my feeling always that the cultural landscape of any place is a three-legged stool: it’s audience, artist and the dialogue that surrounds them. If any of those three go astray you’re probably in trouble. In this case, I think the people of Canberra have taken up the blueprint and used it.”

When I meet Robyn Archer in Sydney to discuss the progress of Canberra 100, of which she is Creative Director, she’s more than pleased with the response she’s had from the people of Australia’s capital, great turnout at events, people thanking her in the street and “projects that are generating opportunities for local artists like never before.”

Legacies

Archer is particularly pleased with the national interest Canberra 100 has generated in the media about the city’s designers Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin: “That was intentional, to say why don’t we just hark back to bold beginnings and ideals and aspirations. My focus since the beginning of the year has been, what’s the legacy going to be? It’s good to have everything going on this year but we hope that the seeds we’ve planted are going to have a legacy into the future.”

One legacy Archer points to resides in Canberra 100 promoting “just how much fodder there is for artists in terms of the Australian story in places like the National Film and Sound Archive, the Library and Museum. Terrific reference points all over the place.”

Street swag art

Among a number of exhibitions at independent galleries that have impressed Archer, she was particularly taken by Flipside curated by Merryn Gates: “an exhibition about homelessness in Canberra. Street Swags are made by Jean Madden in Brisbane in consultation with homeless people. They’re very light canvas with a light foam lining, fold up as a shoulder bag and have been given to 26,000 homeless people already. There’s one of these in the show but it’s beautifully printed by Gates with images of Walter and Marion Burley Griffin (Dream City, 2013). I love it and we’re hoping to do a project about homelessness in the capital in the future.”

Parties at the Shops

Archer is especially delighted by the success of Parties at the Shops. “My thinking right at the beginning was well, if we can do you a spectacle on 11 March, on the actual birthday of the city why don’t you do it for yourselves as well—parties at your local shopping centre that you can walk to. Well, it was unbelievable. I visited 17 on the one day. In Yarralumla, the residents had a dinner. There were 450 people sitting outside under the trees eating and dancing to a Zydeco band. The one at Watson was similar with about 600 people. But what was so moving was a really tiny place whose one shop is a graffiti-ed convenience store. Two hundred and fifty people had a barbeque, double garage doors rolled up and DJs playing. Out of that they decided they’d revive the Residents Association. They were saying really beautiful things like “next time—already with the idea that there would be a next time—we’ll invite the people from the suburb next door because all their shops have closed. I think that Parties at the Shops and You Are Here (the 10-day multi-arts festival spread around the CBD showcasing Canberra’s emerging and alternative arts communities) are the real ‘no-brainers’ that will survive.”

Celebrating the cultural calendar

Part of the reason for Canberra 100’s immersive character is Archer’s incorporation of the city’s annual events and national conferences into the year long celebration: “It was really about profiling the natural cultural calendar of Canberra anyway—things like the Canberra International Music Festival are really fantastic. It’s one of the festivals that I think should be encouraged in the future, mainly because Chris Latham has brought it into Griffin-inspired venues in the series of three that he’s done. So as with the best festivals, you get to explore the city. What I did was to look at what was on the cultural calendar already, make people aware of that but then plug some of the gaps and introduce some new ideas. There are so many conferences on and, to my chagrin, so many opening or closing on Saturdays and Sundays. Days off are now a thing of the past (LAUGHS). So many organisations chose to have their national conferences in Canberra this year.”

Archer has to make many an opening speech during Canberra 100. The day we meet she’s to open an Arthur Boyd exhibition “about his political life, at the Museum of Australian Democracy—part of the ongoing series they’re running all year called The Art of Influence, which is all about arts policy and political engagement. Last week was the Gallery Guides’ Conference, next I address the Midwives’ Association and then the Museums Australia Conference. So, Canberra 100 is big, very mixed and it’s full-on the whole time—and it jumps around violently from things I know little about to things with which I’m very familiar.”

Science and art

Science is a significant component of Canberra 100, in Science Week and beyond. “The science credentials of Canberra are amazing. There’s been a series of Canberra Nobel Laureates coming back to talk about their work. But the interface between art and science is also enormous,” says Archer, citing the work of Erica Secombe, who has been working with CSIRO but also now with the ANU Department of Nuclear Physics using their imaging technology. Erica looks at what they’re doing and, to some extent, her investigation is driving some of their research, which is the best possible collaboration. This is again about Canberra as a resource. And also about artists who come from science families: David Finnegan, one of the founders of Boho Interactive, his father was at the CSIRO and Huey Benjamin who’s composing for Garry Stewart’s new work for the Australian Ballet, Monumental, is from a science family in Canberra.”

Celebrating First Australians

A major component of Canberra 100 is the Indigenous program: “I’m particularly proud that the people who’ve produced that program are in Mildura—Helen Healy’s HHO Events. It’s really nice to think of the national capital stimulating a very big national Indigenous program that’s operated out of Mildura.

“Kungkarangkalpa: Seven Sisters Songline, performed by senior dancers from Central Australia outdoors at the National Museum was fantastic. Wesley Enoch did a great job on that of telling the story very, very honestly. He provided just a beautiful simple, screen-based background for traditional performers to bring their story down for the first time.” With a large program spread across the year, Celebrating First Australians has its own printed program (also available online).

“Canberra 100 is all about changing perceptions of the national capital—it’s actually made people aware of a very strong local Indigenous community. We’re showing the work of many, many local performers and artists. Jenni Kemarre Martiniello is a glass artist who has been working with Venetian glass technique to create interpretations of eel traps—they’re absolutely exquisite. She has a studio at the Canberra Glass Works. This celebration is about a young singer like Anita Barlow and established ones like Dale Huddleston and his family. The ACT’s unique in that it has an elected Indigenous body that looks after the interface between local policy and consultation directly with the ACT government, and they told me, ‘You’ve really got to get to the grass roots of stuff. There’s a mixed touch footie carnival at the Boomanulla Oval. Get out and do [Canberra 100] there.’ Locals don’t think that there’s an Indigenous community here and yet we’ve been taken out by one of the rangers, Adrian Brown, to rock art sites that are dated to 800 years old and they’re 30 minutes out from Canberra.”

Coming up in the Celebrating First Australian’s program is Big hART’s Hip Bone Sticking Out, QL2’s Hit the Floor Together which is being led by young Indigenous choreographer Daniel Riley McKinley and a forum entitled Inside Out—“the first day will be an overview of the past and where activism has got us to this point. The second day is given over entirely to younger groups—particularly those who are using cultural pathways for activism, artists like Warwick Thornton. On the second day it’s much more about people who are taking the cultural route to demonstrate and others working from the inside. Nothing could be plainer than Thornton’s Samson and Delilah to tell you how it is and then it’s up to you to go there. Others like Tim Goodwin are going inside. He’s a terrific lawyer who has been working for the High Court in Melbourne. He was a Fulbright Scholar. He’s going the legal pathway—more the Larissa Berendt sort of path. So, many, instead of demonstrating on the outside, at the fringes, in the street, are coming into the professions, getting all the craft and skills and doing it that way. But whenever I say that to some senior Indigenous leaders they say, ‘Yeh but is it just a cop out? Are they just doin’ the art and not doin’ the stuff on the streets, ‘the hard stuff?’ That forum will be on in association with NAIDOC Week and there are a number of exhibitions as well.”

Archer says of Hip Bone Sticking Out, that Big hART “has been working in Roebourne in WA for a long time and Roebourne is, as we know, a very divided community over whether mining and its returns are a great thing or are just going to stuff everything up. Big hART have been working mainly with young kids and really looking at a very optimistic future. Whatever happens the kids will take it on, bring it on. We’re giving free tickets to the local Indigenous community so they actually get to see all the shows and meet and talk to the artists.”

Future Canberras

If Canberra 100 asks locals and all Australians to take a fresh look at the city, its creative history and what it offers now, not least for emerging artists, what has been the role of the event in terms of speculating on Canberra’s future?

Archer says, “I think the most significant change to Canberra will happen if the high speed rail ever gets up—whether that’s in our lifetime or not, but at some point it will, and that will change things. If you can live in Canberra and be 45 minutes away from your job in Sydney there will be a lot more people who will want to live in this pristine bushland and that will drive a whole lot of necessary environmental changes because there isn’t really enough water even for 370,000 people. Scrivener the original surveyor thought there was enough for 250,000 people and he was right but the need has become more and more pressured and with Climate Change it’s exacerbated. One presumes that necessity will be the mother of invention.”

The issue of the future was addressed by offering landscape architects the opportunity to imagine a Canberra of the future in the CAPITheticAL design competition. Archer wanted the entrants “to put themselves in the same place as the competitors who had to design the city in 1911” but for a 21st century Canberra. She points out that for many of the entrants sustainability and a sense of democracy were high priorities. There were 1200 expressions of interest and 114 entries from 24 countries from which 20 were chosen for exhibition at the Gallery of Australian Design and judging for a $70,000 prize. The winner, Ecoscape’s The Northern Capital, which would doubtless appeal to Tony Abbott and Bob Katter, maintains the ACT city for Parliament and the public service, but creates a new city “on the edge of another manufactured lake, namely Lake Argyll in the Kimberley region… to deal with Asian and northern development.”

Second prize went to the quite beautiful if equally disturbing Sedimentary City Canberra, aerial views of city and surrounding landscape into the future. Curator Michael Desmond describes the entry, created by Brit Andresen and Mara Francis of Architecture and Urban Innovations Collaborative (A+UIC), as dealing with time, “shrinking and contracting both the lake and the city in response to drought, fires and the full effects of climate change and economic fluctuations, showing the city as a living organism, tuned to the epic history of humanity” (catalogue).

Skywhale

First Flight, Skywhale, Patricia Piccinini

photo Mark Chew

First Flight, Skywhale, Patricia Piccinini

Canberra-born visual artist and sculptor Patricia Piccinini has strikingly realised a melding of past and future in Skywhale, a full-scale hot air balloon in the shape of a recognisably Piccininian hybrid, here a multi-breasted, benign maternal mammal, lingering contemplatively over the Australian landscape—evoking both ancient mother goddesses and evolving mutancy. Not surprisingly, Skywhale has been greeted with both repulsion and fascination, and some nonsensical and censorious politicking. Festivals that celebrate the past certainly sustain and reinvigorate legacy but unless they have vision, asking where are we are now and where are we going, and demonstrate these—they will have no legacy of their own to bequeath to future generations. Robyn Archer has built a centenary with an eye to the future.

For the program for the next six months of the Canberra Centenary go to canberra100.com.au and look out for a forthcoming RealTime e-dition guide to the festival.

–

See Robyn Archer talking about Canberra 100 back in November on RealTime TV

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 18-19

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Noriyuki Kiguchi (Akumanoshirushi)

photo Hideto Maezawa

Noriyuki Kiguchi (Akumanoshirushi)

Asakusa, Tokyo. The temples remain but the modern skyline grows: The Tokyo Skytree is the tallest building in the world; and Asahi Art Square, host of the Azumabashi Dance Crossing showcase, makes up for its smaller stature with an ostentatious tear-drop sculpture on its roof. Lit up at night, it is affectionately known as the “golden shit.” How the modern and traditional often seem incongruous in Japan.

In previous years the focus was on Azumabashi DANCE Crossing, but with the selection of works by curator Keisuke Sakurai, himself a choreographer and dance critic, the emphasis is now on CROSSING: hip-hop-rakugo, turntable-butoh, Zen-7/11-thrashmetal…in short, hybrid-performance.

The festival’s theme was “groovy bodies”—a rather vague and none-too-serious theme for post-tsunami, post-Fukushima Japan. Addressing this issue in local media before the event, Mr Sakurai said, “This 2013 edition of ADX was conceived in an attempt to reconsider not how art can serve an instrumental or practical purpose, but precisely its apparent ‘uselessness’—as well as the potential usefulness of this futility, if you will.”

The evening began with dance from 21seiki Gebageba Buyodan. It was a wishful and grotesque piece that shifted between mimed daily chores and the movement of addiction in daily life…perhaps a literal interpretation of “groovy bodies.” Danced to music best described as Middle-Eastern-ragtime, these abstractions of movement were playful or sometimes monstrous, such as the gathering of all the red-shirted dancers centrestage, standing back-to-back in a circle, to mime the eating of giant onigiri (rice balls). Subtle changes in pace built a tension that was sadly cut short by the allotted 20 minutes.

Next was Noriyuki Kiguchi’s irreverent meta-theatre. A man dressed as topographical Tokyo revs up the audience while on the screen behind him entries from Kiguchi’s diary explain possible ideas, lack of arts-funding and the difficulties of creating a piece for ADX. Kiguchi himself is called centrestage where he receives a shocking slap for said navel-gazing. This direct yet fractured social commentary is but one example of the influence of Oriza Hirata’s colloquial language style of theatre in the 1990s. Kiguchi’s final image—of the Japanese Emperor (who made a rare public appearance after the Tohoku earthquake) dancing the salsa while his wife (a man dressed in drag) encourages him with over-polite smiles—seems at first to be naff and inconsequential, but perhaps best grapples with the relationship between public face and private grief.

The offering from Toukatsu Sport was just as fractured in its conception. Projected on the back wall was the opening to Roman Polanski’s film adaptation of Carnage. Before we enter the apartment of the sitting-room drama the strings of the soundtrack are faded out and replaced by House beats, the film replaced by turntables, and two women who walk on stage dressed in hip-hop bling, carrying stuffed toys. They begin a rapid-fire monologue of what my +1 would later call “journalism of complaint”: about the venue; about recent pregnancy; dissing other theatre groups. Images alternate between Carnage, turntables and traditional rakugo (pithy anecdotes laden with puns and comedy). Language barrier aside—even the Japanese around me were struggling to keep up with the speed of the dialogue—it was enthralling to watch the English, American and Japanese story-telling in mash-up.

After the interval, the band core of bells opened our ears. When a young man walks into a convenience store to trade in his soul for a new one (for Y7400) he is invited to play guitar in a noise-band whose frontman is a growling Shinto God. Ko Murobushi performed butoh, with music provided by Yoshio Ootani’s distorted, looped saxophones and chains on turntables. Joined by members of the former’s company, each performed their own personal calligraphy of a collapsing city while Ichiro Endo, cheerleader, performed a heartening if baffling motivational dance. The difficult joy of ADX is having all these artists brought together but being unable to create or comprehend a super-narrative.

The evening concluded with Takahiro Fujita’s Dots, Lines and the Cube. His company, Mum and Gypsy, has been focused on a form of post-dramatic theatre since its formation in 2007. DLC tells the story of a kidnapped girl from the perspectives of three characters. The actors hopscotch around lines created with masking tape. The energy on-stage is that of a child’s wind-up toy; when the energy of a refrain is expended the story is wound up again and told from a different perspective, in uncanny mimicry of the news cycle of a traumatic event. It has all the uselessness of a game, but perhaps, as Mr Sakurai suggested, there is a potential usefulness in the futility.

Azumabashi Dance Crossing, Asahi Art Square, Tokyo, 29-31 March

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 20

© David Maney; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

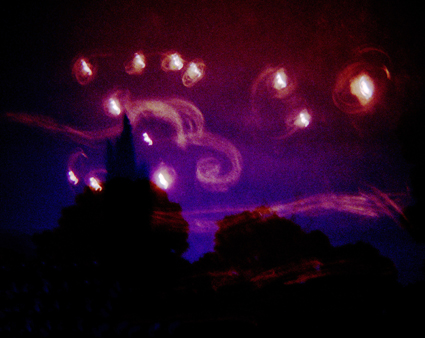

Bruce Ramus, Light Hearts, Light in Winter Festival, 2011

photo Jason South

Bruce Ramus, Light Hearts, Light in Winter Festival, 2011

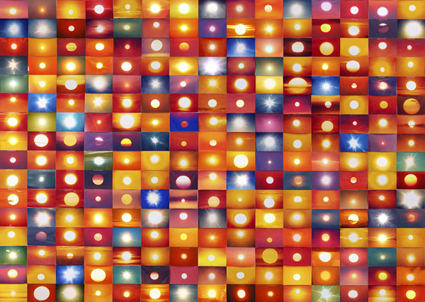

Canadian Bruce Ramus, a master of what he calls “integrated light art,” resides in Melbourne, his company’s base for the creation of large-scale public artworks. In 2011 he made Light Hearts for Federation Square’s The Light in Winter festival; he’s lit the Sydney Opera House for VIVID, illuminated Darling Harbour with Luminous, lit the Wintergarden facade in Brisbane and turned a sports park, AAMI, into a constantly morphing light sculpture.

Earlier in his career Ramus was responsible for the spectacular lighting designs for U2 and REM and their huge concert audiences. Today he is focused on the use of light to engender a sense of community in a different way, and sustainably so. I spoke with Ramus about the making of and the goals for a new, commissioned work for the 2013 Light in Winter, The Helix Tree.

You’ve had a long association with the relationship between light and music and of course the voice when you work with bands, but the brief for Light in Winter one looks pretty interesting in terms of its requiring a direct relationship between light and voice. Is it a relatively new thing for you?

We’ve been working on pieces that are interactive for about three years now. We installed a much larger one at Darling Harbour last year and that was very interactive, but not for voice, and the last piece we did in Fed Square, Light Hearts, had a very low-tech interactivity about it, encouraging children to make lanterns.

But we’ve been putting together a portfolio of ideas, software and code to enable us to make the most sense of these opportunities and make it mean something. It’s our way of trying to create spaces for community engagement with light.

How is this work specifically interactive?

It responds to two elements of voice, pitch and amplitude. The amplitude alters the brightness of the lights and the pitch changes the colour. The idea is that each evening at dusk a different choir comes to the piece and sings it to life. They will sing directly to it and make it change. The movement is pre-programmed but the actual volume of the voices allows the brightness and the movements to be revealed. The pitch changes the colour of the light as it’s moving.

Then, once the choir finishes, there’ll be a period of time when the public themselves can sing to it. After that it will go back to its own program and its own rhythm. That will be happening from 8.00 o’clock each evening until dawn the next day. Which gives the tree a chance to breathe at its own rhythm.

What kind of microphones and sensing devices are you using?

We’re experimenting with that now. I don’t know the specifics of the kind of microphone that we’re going to choose; that’s down to our sound designer. But it will be a centralised microphone. It’s not like a vocal microphone that you sing into. It’s directional, picking up the voice but it has a very narrow band of reception so it’s not picking up the wind and the traffic—just the voices that gather around it.

Your work is quite sculptural. How does this manifest in the Helix Tree?

I started to look at the helix as a shape and I was inspired by the way it depicts an infinite flow of energy; it just keeps twisting and turning in space. I also noticed that helixes don’t impose on other helixes in nature. They intertwine—they’re harmonious. You don’t find competing helixes. They co-exist and create this harmonious energy. You can see it in trees and in the DNA of all of us, in our ear canals. Because community engagement is such a huge mandate for Federation Square, I began to see how it might make sense as a shape for this project. I saw how it could symbolise healthy families and communities where you have individual strands of energy— people—and when they don’t impose on each other, there’s harmony.

And the idea for the tree itself?

I loved the notion of power without resistance, the adaptability and flexibility of a tree where it is in true harmony with its environment. It gets pushed and pulled and moved around by nature but it maintains its strength without resisting.

A very strong metaphor. What materials are you using to build the tree?

The tree itself is built from mild steel pipes made from largely recycled steel. The large helixes are 219 mm wide and the smaller ones are 169 mm. Each one of those is about 21 metres long, making the overall height of the tree about 13 metres.

Is it an abstract shape that evokes a tree?

Yes. There’s a trunk where all the helixes begin within about a metre and a half of each other. So it’s very compact down at the base, and by the time the branches are at their widest they’re about 17 metres apart. It’s abstracted but one can certainly get the reference that this is a tree.

What kind of lighting devices are you using?

It’s a type of neon, but not actual neon with gas—that’s a little bit impractical for such a short period of time. We’re using LED neon that looks very similar but is essentially an RGB LED encased in opal plastic. So there are four strands of that on the large helixes and one on the small. There are 21 of these 21-metre long helixes. The idea is that the tree feels luminous. It doesn’t have fixtures attached to it per se, so it will feel like the tree is emanating light.

Do you feel this work has extended your own practice in some ways?

It sure has! Doing sculptures of this size, starting from nothing and doing the engineering design and fabricating this amount of steel, it’s very complicated. Imagine you’re looking at three seven-metre long pipes that are 220mm wide. That’s a big pipe. We bend that pipe and then we cut the pipe into about five sections and then twist each section, say five degrees, and re-weld it. The next one gets twisted seven degrees and re-welded. The next one is twisted 10 degrees and re-welded. So you get a helix curve out of something that doesn’t look like it should curve. And then when we go to erect it…it’s a mind-bender. And that’s only the tree, there are still the three ponds that it will stand in to build, and a very large viewing platform…all to give space for reflection.

It’s been a great learning process and a wonderful extension of my ability to see in three dimensions and to visualise. It’s too easy to grab the re-size tool on a CAD program and drag it till it says 13 metres. I’ve never tried to put so many very complicated curves into one very compact space.

So it’s turned into a major sculptural challenge?

Yes, it has. The site itself throws up challenges as well because, as you know, it is built over railway lines so there are significant weight-loading restrictions. The square is also covered by catenary wires that are about 14 metres tall, which make it difficult to get a crane in between all the wires…then there’s the high pedestrian traffic and the limited time…it’s not straightforward, but we love a challenge!

The great reward will be a sense of communality.

That’s the hope…that it will feel like a healing energy, some kind of communal harmony; that it brings some peace to the centre of a city—especially the one I live in. That’s a feeling that for me is rare. It’s not every day you get to put something like this in place. And we’re hoping that once it’s done it will be purchased for permanent installation.

The Light in Winter, director Robyn Archer, Federation Square, Melbourne, 1-30 June

RealTime issue #115 June-July 2013 pg. 21

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Man Who Planted Trees, Puppet State Theatre Company

photo J Barker

The Man Who Planted Trees, Puppet State Theatre Company

Castlemaine. A town rich in gold mining history. Set around a river that never runs (but often floods). A town where every second person you meet is a writer or artist. The best of inner city—coffee, dumplings, markets, gigs crammed into two big blocks. The best of rural as you watch roos and rosellas in your backyard after rain. A town where beautiful old buildings stand and decay. And every two years, an ambitious 10-day program of theatre, music, literature and visual arts.

Apparently you need a grandparent buried in the cemetery to call yourself a local, but I’ve been here nine months and this is my first festival. I can walk. Everywhere. The laneways are covered in works by high school kids. One stencil of a reindeer on the wall of the Bendigo Bank—with the accompanying inscription “Christmas is a lie”—causes outrage. A stealthy graffiti artist comes at night to blacken the inscription out. Makes front page of the local rag. You can’t offend Santa in this town. Or what’s his name, Jesus, for that matter. But does the teen artist remember a time when Christmas was about more than Masterchef-ing the BBQ, or cheap gift tags from the two dollar shop?

“I need a dollar, dollar, a dollar is what I need”

[soul singer, rapper Aloe Blacc]

Ranters Theatre, This Is Me—Now

Actually, the festival is rich with insight into what young artists think. In This Is Me—Now, Ranters Theatre creates video portraits with five teenagers from the region: Ruby Benedict, Ruby Scott, Bonnie Cook-Hain, Eamon Coulthard and Holly McNamara. The videos are about identity and space, and the rules of longing and belonging. Holly is a girl straight to camera, sitting in the bush. She describes it as a “very unconditional space…doesn’t need anything added to it” as she performs a soft-spoken song on her ukulele. Ruby Benedict does a performance piece to camera, becoming ‘the huntress’ on a red velvet couch. Ruby Scott turns her back, drawing a surreal cityscape that morphs into a creature as her voiceover draws me in. Bonnie, swinging her legs over the railway platform, sees herself as a girl who can’t conform—“most girls want to fit in…the in crowd”—and doesn’t care. In her white roller skates she talks about her love of books, music, family, friends and contact sports: “I like being pushed around on the field…Being different makes me feel confident.” Eamon imagines Castlemaine in a state of heightened anxiety—‘lock down’, ‘code red’—a place undergoing rapid (and sinister) change, where spikes are placed on the tops of buildings to ward off birds, even though no birds ever land there.

The Republic of Trees

But the birds have plenty of other places to land. Castlemaine is the kind of place where gleaning is encouraged. Organised groups fossick from trees ripe with apples and pears, distributing extras to community centres and local childcare. A living stage at the festival has planters. Tales of trees, of eco-survival, permeate the performances. In The Republic of Trees (based on Italo Calvino’s novel The Baron in the Trees), a wandering minstrel show that meanders through beautiful Vaughan Springs, we encounter a dining table at dusk, with butlers in waiting and young women walking their dogs around the perimeter. We learn of creatures that can cross the country east to west, their feet never touching the earth. At midnight, Cosimo (Matt Wilson) joins the canopy, vowing never to set down again. Wilson’s physical theatre experience shows as he glides through trees on ropes and ladders, slippery with condensation. As we hear of God pissing down, rain starts to fall on us. Bookshelves and chairs are suspended, pulleyed, as we hear tales of yearning, philosophy, romance. For Cosimo, all that matters is principle, his ideologies of freedom, even if it means losing out on love. But his act becomes commodified, a display to be rolled out for an audience: “see nature’s greatest marvel.” And at what point—wars, horrors, exile, environmental degradation—is it more important to touch the ground?

The Man Who Planted Trees

In The Man Who Planted Trees, a farmer in Provence seeds hundreds of plants a day, in an arid region where nothing grows except wild lavender (the performers waft scents like lavender and mint over the audience with large fans). Scotland’s Puppet State Theatre Company takes us to meet him, accompanied by a dog (the true star of the show). The performance works brilliantly by paralleling two narratives: the straight parable, along with the dog’s meta-textual journey. A dog who just can’t help himself, he keeps butting us out of the narrative—“It turns out my eyes are buttons! Amazed I can see anything at all!”—to great comic effect. The timing is wonderful, the writing simple and complex (at once) and the show works on the level of all great children’s storytelling (The Muppets, Aardman) where the humour comes from where the two strands of narrative merge.

Site-specifics and Transplant

Such as they are, Transplant

photo E Dutra

Such as they are, Transplant

Back down on the ground and I head to the festival’s biennial visual arts program (curated by Deborah Ratliff), where the site-specific works are outstanding—Pia Johnson’s shrine of Chinese red packets, Hong Bao; Bindi Cole’s dialogue, I forgive you, at the Theatre Royal cinema; Tara Gilbee’s apothecary at Tutes Cottage; and Clayton Tremlett’s character sketches at the Old Police Lockup—before entering a tiny cube-theatre, and donning my scrubs for the puppetry production Transplant. As an operation goes awry and a woman unleashes frogs and flowers from her stomach, the actor-cum-doctor and his unpredictable patient manage to unnerve everyone to the point where I am the only audience member left in the room.

Chants des Catacombes

Chants des Catacombes

photo Pia Johnson

Chants des Catacombes