Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Amped, Chronology Arts and Ampere Quartet

photo Hospital Hill

Amped, Chronology Arts and Ampere Quartet

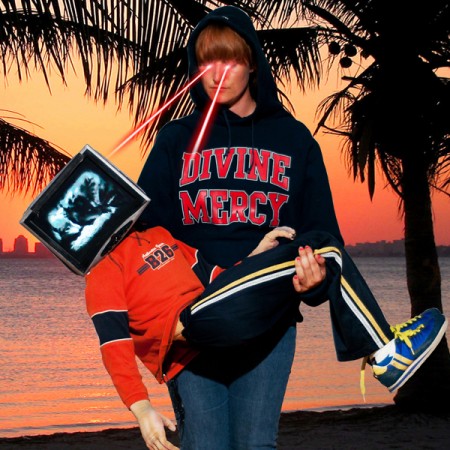

ANOTHER THURSDAY EVENING IN PENRITH: THE RETREATING SUN THROWING THE BLUE MOUNTAINS INTO SILHOUETTE, FLOCKS OF CHITTERING PARROTS SETTLING AMONG THE LEMON-SCENTED GUMS, A SEA OF BRAKE LIGHTS GLITTERING ALONG THE M4.

Meanwhile on the grass and raw dirt ‘community space’ between the plaza, the area’s venerable mall and the Joan Sutherland Centre (its more recent rechristening “The JOAN” sitting uneasily with its determinedly highbrow aspirations), groups of young people huddle in clusters, hanging out, catching up and filching cigarettes while experimental guitar quartet Ampere present Amped, a free performance of works recently commissioned through Chronology Arts.

Julian Day’s appropriately named Dusk matched the lengthening twilight, wrenching descending tones from Zane Banks’ solo electric guitar, punctuated only by the dull murmur of teenage courtship. Next was Steffan Ianigro’s Music of Symmetry, wailing dissonance counterbalanced with closely spaced, almost claustrophobic chords; a stepwise ascent suggesting impending horror. A strange atmosphere resulted, the well-mannered attention offered by dedicated nu-classical listeners on the grass sitting at odds with random yelps of female laughter, Ianigro’s careful conducting of the quartet (Banks, his brother Jy-Perry, Matt McGuigan and Mat Kurukchi) seeming overly precise beneath the fluorescent glare of the mall.

Matt McGuigan, Mat Kurukchi, Amped

photo Hospital Hill

Matt McGuigan, Mat Kurukchi, Amped

Fausto Romitelli’s TV Trash Trance, presented by Jy-Perry Banks on solo electric guitar, was apparently not to the liking of some, “Fuck you!” being yelled in the background— though it was unclear at whom the ‘you’ was directed. Although the volume was criminally low (Banks’ curly mop failed to flail nearly enough), the whirring loops of static established early in the piece provided ample basis over which to squeal and whine in the latter portion, the sound of a faulty connection being used to rhythmic effect before the lot collapsed into Lovecraftian sludge, eliciting some enthusiastic applause from at least one group of junior critics.

Alex Pozniak’s Small Black Hole, followed suit, the quartet gradually building a sliding, groaning texture redolent of the collapse of buildings or tectonic drift. Amid the shifting layers, tremolos suggested the distant ascent of a space shuttle, the hulking sound of aircraft engines emerging from dobro-style slides. While kids stole each other’s baseball caps, providing a clear invitation for a good chasing, a cataclysmic crash loomed in the air, the music spiralling towards an unavoidable impact before fading to nothing. Well received and highly effective.

The experiment in community engagement was rounded off with Phill Niblock’s Guitar two, for four. Emerging unhurriedly from its opening drones, the work was accompanied by a complementary black and white film (as is Niblock’s wont) featuring industrial imagery—gauges, whirring gears, liquid metal being poured—matched to piercing overtones, the guitar’s potential for violence finally unleashed, a blaring surface licked by flares of feedback perhaps unavoidably bringing to mind the consumption of workers’ bodies in Metropolis. And that was that, scattered applause dispersing amid puffs of underage smoke.

Aurora Festival of Living Music: Chronology Arts and Ampere Quartet, Amped, Joan Sutherland Performing Arts Centre, May 10; www.auroranewmusic.com.au

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. web

Synergy

photo Karen Steains

Synergy

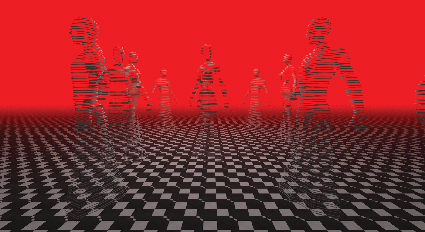

SOME STRANGE CONJUNCTIONS THIS EVENING, AN INVIGORATING PROGRAMME OF NEW MUSIC PRESENTED BY SYNERGY PERCUSSION BEING PERFORMED ADJACENT TO A KICKBOXING AND PRO-WRESTLING MEET IN THE MAIN FOYER OF CASULA POWERHOUSE.

Though some seemed uncomfortable with this situation—“Oh my god!” the festival director was heard to mutter as muffled grunts and thuds mingled with the first sounds of James Rushford’s Go—the sound bleed added an element of indeterminacy to proceedings that was not entirely incongruous with the prevailing aesthetic, though the recording technicians from the ABC could probably have done without the challenge.

Rushford’s music conjured an eerie fragility, chirrups, squeaks, tinkles and chimes suggesting the cradle or even the emergent consciousness of the embryo. Utilising the soft hiss of gravel and sand as well as bowls of marbles, the performers busily created a sparse, playful texture, resting only as the swell of a pre-recorded electronica track, drowned the live sounds with menacing imminence—an effect somewhat undercut by the cheering next door.

No such problems with Alex Pozniak’s Groove Destruction. Taking its cues from “noise music [and] heavy metal,” Pozniak’s first piece for percussion aimed to explore the “extroverted” side of the ensemble, the four players attacking a phalanx of un-tuned drums with gusto. Establishing then annihilating rhythmic cycles, the piece moved through phases of instrumental delicacy before allowing the group to indulge an unadulterated joy in hitting things, Timothy Constable becoming so involved in the energy of the music that he inadvertently smashed a cymbal to the floor.

Inspired by Xenakis’ Pleiades, Amanda Cole’s Intermetallic provided a calming counterbalance. Writing for metallic blocks of ostensibly indeterminate pitch, Cole worked out at what frequency each vibrated, pairing “similarly dissimilar” tones to achieve a shimmering, not-quite-consonant effect. Growing from an almost-pure fifth, the piece seemed suspended in liminal space, redolent with the half-heard, the almost glimpsed. Armed with soft mallets, the performers offered some of their most sensitive playing of the evening, producing a gentle rippling that recalled all the dappled grace of the gamelan.

Synergy upped the energy once more with their own work, The Fives, with Alison Pratt taking a breather while Constable, Bree van Reyk and Joshua Hill returned to the drums. Using various items, including Constable’s suit jacket, as dampeners, the piece quickly descended into a Kurtzian nightmare, pounded skins suggesting the brutal certainty of a midnight jungle.

More whimsical, though perhaps less effective was Marcus Whale’s Puff, so called because of the composer’s instruction that toy harmonicas be breathed through by each performer for the duration of the piece. Gradually evolving patterns were articulated on wood blocks and thick golden cymbals to create an effect not dissimilar to “a year two’s birthday party,” as Whale drily put it. Although certainly unusual, it was difficult not to breath a sigh of relief once the incessant high-pitched whine of the harmonicas receded into silence once more, leaving nothing but the dull murmurs of ritualised violence next door.

Aurora Festival of Living Music: Synergy Percussion, performers Timothy Constable, Bree van Reyk, Alison Pratt, Joshua Hill; Casula Powerhouse, Sydney, May 5

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. web

© Oliver Downes; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Terumi Narushima, Kraig Grady, Clocks and Clouds

photo Corrie Ancone

Terumi Narushima, Kraig Grady, Clocks and Clouds

WHILE FOLK OF VARIOUS ORIGINS CAME TOGETHER FOR THE STYLISED MACHISMO PROVIDED BY PRO-WRESTLING AUSTRALIA IN THE MAIN FOYER OF CASULA POWERHOUSE, EXPERIMENTAL PERCUSSION ENSEMBLE CLOCKS AND CLOUDS BROUGHT TOGETHER EXOTIC RITUALS OF AN ENTIRELY DIFFERENT NATURE IN THE MAIN THEATRE.

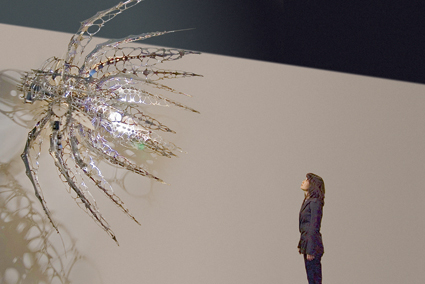

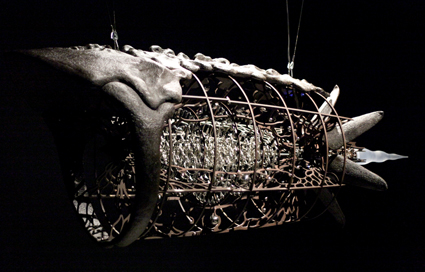

Drawing upon sources as diverse as Harry Partch’s 1973 work US Highball as well as his identification with the meta-culture of Anaphoria (a conceptual landmass whose inhabitants’ key characteristic is a “desire to be foreigners”), composer and general C&C head honcho Kraig Grady’s work, Terrains, Winds and Currents, provided an absorbing listen.

The centrepiece of the work was the set of twelve Meru Bars, an instrument of Grady’s own creation, that rose like mesas behind a harmonium and pair of vibraphones, all microtonally tuned. The Meru, which is fundamentally a set of gigantic bass vibraphone bars, lent the work a gripping solemnity, the hour-long through-composed piece remaining mesmerising for its duration, due in no small part to the skill with which it was approached by Grady as well as Terumi Narushima behind the harmonium and Finn Ryan on vibraphone.

With Narushima establishing a drone on the harmonium, Ryan trod carefully amid the Meru, striking each note with precise reverence, a liturgical quality being compounded by a single bowed note on the vibes. The sound of the Meru seemed to emanate from deep within the earth, its blended resonances suggesting imaginary ceremonies unfolding in forgotten caves. When this opening ‘terrain’ section closed with the exit of the Meru from the texture, the remaining instruments seemed bereft without its subterranean heat.

Meru bars, Clocks and Clouds

photo Gail Priest

Meru bars, Clocks and Clouds

This sense of desolation faded as Grady and Ryan generated a new urgency on the vibes, the harmonium providing flashes of melodic material, the effect being that of wind over wet rock, swift and indefinable. Indeed the music here was elemental, almost lysergic, the aesthetic bringing to mind the broken musician in Tim Winton’s Dirt Music. Consigned to hermitude, he finds solace in a makeshift drone, the sound of which seems to contain the world, “like the great open spaces of apnoea, the freedom he knows within the hard, clear bubble of the diver’s held breath. After a point there’s no swimming in it, just a calm glide through thermoclynes, something closer to flight. Within the drone, sound is temperature and taste and smell and memory, wucka-whang.” Grady seemed to be striving for something similar here, the rapidly oscillating tones suggesting rippling clusters of light, refractions in which the mind might become lost.

All of which would be so much twaddle were it not for the extreme discipline that Grady, Ryan and Narushima brought to the material, seamlessly coaxing distinct shifts in texture from the preceding flux. None more effective than the return of the Meru, the roiling bouyancy of the previous section giving way to a solemnity worthy of the disappearance of species, static vibe chords reverberating in isolation over the terrestrial groan of the bass bars. This was an hypnotic and moving song for the earth.

Aurora Festival of Living Music: Clocks and Clouds, Kraig Grady, Terumi Narushima, Finn Ryan, Casula Powerhouse, Sydney, May 5; www.auroranewmusic.com.au/

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. web

© Oliver Downes; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

In this video interview Australian Dance Theatre's Artistic Director Garry Stewart talks with Keith Gallasch about Be Your Self which recently played Sydney Theatre, May 31-June 3, 2012.

For more on the making of Be Your Self see RT94

For a review of Be Your Self in the 2010 Adelaide Festival see RT97

For a full profile of Garry Stewart and his works see realtimedance

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg.

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Lizzie Thomson, Panto, Campbelltown Arts Centre 2011 Dance Residency Project

photo Heidrun Löhr

Lizzie Thomson, Panto, Campbelltown Arts Centre 2011 Dance Residency Project

More and more dancing and more places to dance in Western Sydney: that’s the good news from Martin del Amo’s report in this edition of RealTime. The development of arts centres west of the city is one of the happy legacies of the Carr Labor Government. Campbelltown Arts Centre has a dance curator; in Parramatta FORM Dance Projects presents works in partnership with Riverside Theatres; and Blacktown Arts Centre includes dance in its performance program. Not only do these offer opportunities for dance artists and communities in the region but also engagements for Sydney-based artists as choreographers, teachers and mentors, enlarging the sense of community in NSW dance. There’s further good news from Angharad Wynne-Jones, the Creative Producer for City of Melbourne’s Arts House—Dance Massive will make its third appearance in 2013 thanks to the enduring partnership between Arts House, Dancehouse and Malthouse. It’s pretty much a sell-out event and a great opportunity for artists, audiences and presenters to connect. If you want to keep track of Australian contemporary dance, take a look at RealTimeDance on our website: this invaluable resource provides free access to all of the dance articles and reviews in RealTime from 1994 plus profiles of leading choreographers, video interviews and a feature on dance on film. Dance. Dance. Dance.

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 1

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

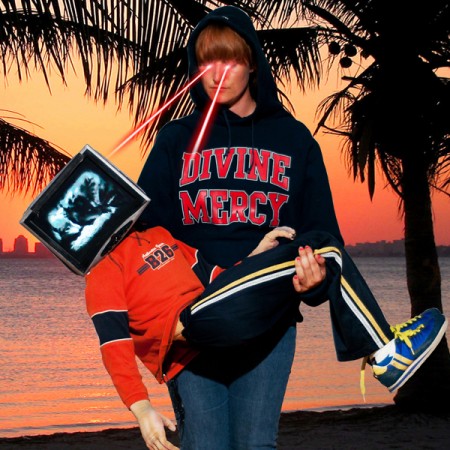

Kristina Chan, Timothy Ohl, SuperModern Dance of Distraction

photo Tim Thatcher

Kristina Chan, Timothy Ohl, SuperModern Dance of Distraction

FROM THE DARKNESS FOUR FIGURES EMERGE. THEY STAND CENTRED IN A LINE. THE LINE IS NEATLY FRAMED BY A SQUARE. FOUR FACES LOOK DIRECTLY OUT TO THE AUDIENCE, FINGERS TWITCH WHILE LIMBS TWIST. A CONGA LINE, OR STRANGE LIMB MACHINE.

Body parts hinge along creases: fingers, hands, elbows, arms—spoking out every which way. Their voices rise in unison from a whisper, repeating: “something is going on, while this is going on.” What is the “something?” What is the “this?” We are immediately drawn into choroegrapher Anton’s inquiry motivated by his question: “what is it to be human in our modern world?”

Pre-modern, postmodern and supermodern are terms turning upon and around the modern. The modern is a consistent descriptor of our present human condition, especially the cultural, economic and technological dimensions. If Frederic Jameson is right, then the modern is a reference point to be fragmented in its post-isms, nostalgically reflected from in its pre-isms, and tempo-spatially reoriented in its super-isms. SuperModern Dance of Distraction turns perceptively on the modern, describing the speeds, spaces and textures of human and human-machine relations in a techno-saturated world.

From formations of four to three observing one, the dancers (Kristina Chan, Timothy Ohl, Robbie Curtis, Sophia Ndaba) rapidly migrate from one configuration to the next, their histories wiped away with large Malevich-inspired blocks of light that scrape the black space. The lighting design (Guy Harding) is consistently constructivist in form, clean, deliberate, boldly white and, on occasion, epileptic and fractious.

When four, the dancers constitute a visual spectacle. In synchronous movements they generate images of a machinic ballet and tessellations of legs and faces spinning hypnotically in a Busby Berkeley water parade. In one sequence, the dancers raise white, hollowed-out squares above their heads, optically thickening their presence. Bodies calibrate: frames for looking through and graphically inscribing the space, frames to frame, shaping these carrier bodies into angular geometries. In another sequence, collapsed white trestle tables provide vertical surfaces that slide along rectilinear lines to block and bounce slamming bodies. The dancers take turns to operate the system, hiding, trapping and distorting the space: a concrete mediation implying a digital logic.

Robbie Curtis, Sophia Ndaba, SuperModern Dance of Distraction

photo Maylei Hunt

Robbie Curtis, Sophia Ndaba, SuperModern Dance of Distraction

In a more literal demonstration, clear perspex held between faces becomes a touch screen: connections are unequivocally established between fingers, glass and manipulated expression. The audience laughs rapturously (perhaps those with iPhone or iPad much harder). The perspex intercepts the kissing lips of two lovers in a moment of ‘distal loving.’ Pressed together they exaggerate the mediated space-time distance that Skype technology attempts to bridge. Their embrace lingering beyond comfortability, they take turns to ferociously straddle each other. The intimate made intensely public raises the real possibility that someone could be watching.

Communication. Upstage in blackout, torch lights flash intermittently, each emitting an idiosyncratic sound. We giggle in this close encounter of some kind. The dancers speak, sing and sound effortlessly, giving some vox to their pop. In an ingenious quartet of couples, they sing into long cabled microphones that swing and swoon like serenading lassos, supporting overall the seamlessly produced pop-inspired score by Nick Wales and Timothy Constable with vocals by Jai Pyne. Tracks of silky-synth smoothness ballasted by crisp hypnotic beats blow an asymmetrical fringe deeper into the eyes—all so distractingly modern.

Connection. The gags and prop-play exaggerate familiar scenarios, like the absurdity of the automated voice machine that never understands us. Caution must be taken, however, when the fast, fragmented and fleeting are both dramaturgical points of departure and justifications for the difficult experience in watching the episodic, disjointed and excessive. I wonder at what point structure and form should resist content. Luckily the more enduring solos reflect a deeper physical ontology (not a mere symptomatic engagement with a world on fast-forward) and so tap into what Raymond Williams calls the “structures of feeling.” Chan, delivered under a red haze, quivers in primordial gasps of arrest, every cell agitated in controlled contortions, tiny, gathered up to the bone, implosion imminent. Ndaba conversely convulses in jelly-like explosions, her jouissance, escalating into maddened laughter, a pressure-built response. Curtis wanders the stage with a disorganised body. Afflicted with “this something,” he is fuzzy and out of focus, snapping joints at the mercy of malfunction.

Refreshingly, there is nothing dystopic nor utopic said about ‘this’ condition, it is not Anton’s point. We are invited to experience, rather than critique. SuperModern is a work of fine collaboration, five dedicated years in development, with places to go, and hopefully in spaces where the carefully constructed geometries of the stage and lighting design can be realised.

FORM Dance Projects & Riverside Theatres, Dance Bites 2012: SuperModern Dance of Distraction, choreographer Anton, performers Kristina Chan, Timothy Ohl, Robbie Curtis, Sophia Ndaba, producer Michelle Silby, composers Nick Wales, Jai Pyne, Timothy Constable, lighting designer Guy Harding, dramaturg Joshua Tyler, set design consultant Julio Himede, Lennox Theatre, Riverside Theatres, Parramatta, March 28-32

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 4

© Jodie McNeilly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Vicki van Hout working on the installation/set of Briwyant

photo Marian Abboud

Vicki van Hout working on the installation/set of Briwyant

IN JUNE 2011, AFTER SEEING BRIWYANT I WROTE, “VICKI VAN HOUT’S CHOREOGRAPHY IS SOME OF THE MOST IDIOSYNCRATIC AND INVENTIVE SEEN IN AUSTRALIAN DANCE FOR A LONG TIME AND HER TEAM OF DEXTROUS DANCERS EXECUTE IT WITH HIGH PRECISION, UNBELIEVABLE ENERGY, HUMOUR AND ATTITUDE.”

Briwyant is touring to Melbourne and Brisbane, offering audiences the opportunity to experience something quite unique in contemporary dance. The choreographer, who also appears in the work, writes, “Briwyant is inspired by bir’yun: brilliance, shimmer and shine. In Yolngu traditional painting, bir’yun is the effect of intricate crosshatched patterns creating a sensation of shimmering movement over the painting’s surface, a manifestation of ancestral forces.” With her dancers, her own design and her media arts collaborators Van Hout creates resonating physical, aural and visual shimmerings in Briwyant. KG

Briwyant, Malthouse, Melbourne, July 4-14; Brisbane Powerhouse, Aug 1-4

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 4

© RealTime; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jannawi Dance Theatre, Megamaras, film, Blacktown Arts Centre

photo Andrea James

Jannawi Dance Theatre, Megamaras, film, Blacktown Arts Centre

WHO WOULD EVER HAVE THOUGHT THAT WESTERN SYDNEY WOULD ONE DAY BECOME A BASTION OF INDEPENDENT CONTEMPORARY DANCE? SURE, THERE HAS LONG BEEN A TRADITION OF SOCIAL AND FOLKLORIC DANCE IN WESTERN SYDNEY, PARTLY DUE TO ITS STRONG LINGUISTICALLY AND CULTURALLY DIVERSE DEMOGRAPHIC. THERE HAS ALSO BEEN A LONG-TERM HIP HOP DEVELOPMENT IN THE REGION AND THE EMERGENCE OF PARKOUR CREWS IN BANKSTOWN AND THE FAIRFIELD AREA. BUT CONTEMPORARY DANCE?

It is true that artists such as Anandavalli (Lingalayam Dance Company) and Annalouise Paul have been presenting contemporary culturally diverse dance at venues like Riverside Parramatta for quite some time. And yet, there is no denying that in recent years a growing number of NSW-based independent dance artists have switched their attention to Western Sydney, where a variety of arts organisations and presenters offer ample opportunity to both develop and present new work. So what is the reason for this sudden boom.

According to Kim Spinks, who formerly managed state funding for theatre and dance and is currently Manager Capacity and Development at Arts NSW, there are several factors. One is the implementation of Arts NSW’s Western Sydney Arts Strategy, a long-range initiative drawn up and put into effect in 1999. It had a substantial funding program attached to it ($37m 2001-2010) and targeted all artforms. However, as Spinks points out, at the time the University of Western Sydney (UWS) offered the only tertiary dance degree in New South Wales which became a factor for organisations such as Ausdance NSW to invest in dance in Western Sydney and attempt to build an infrastructure around it. Ironically, the dance course at UWS folded after a few years but, by then, the rise of dance development in the area was well on its way.

Another great shift occurred through a major capital commitment of over $20m from the Carr government in the mid-2000s and a combined spend of over $55 Million from state and local governments. It affected the arts centres in Campbelltown, Blacktown and Casula and involved turning visual arts spaces into multi-art centres. As a result several of these organisations incorporated dance into their programming. So let’s have a look at some of the key players:

form dance projects

FORM Dance Projects, known until recently as Western Sydney Dance Action (WSDA), was founded in 2002, evolving from an outreach initiative Ausdance NSW set up in response to the Western Sydney Arts Strategy in the late 1990s. Since its inception, the organisation’s most important partnership has been with Riverside Theatres under the directorship of Robert Love. Initially an auspiced project, FORM now operates independently from Riverside but presents work in partnership with them. The cornerstone of its presentation program continues to be the long-running Dance Bites series. Initiated by WSDA’s inaugural director Kathy Baykitch in 2003, Dance Bites has gathered momentum in the last couple of years with highly successful productions such as Narelle Benjamin’s and Francis Ring’s Forseen, Craig Bary’s and Lisa Griffith’s Side to One (see interview, RT105) and most recently Anton’s SuperModern Dance of Distraction (see p4). Later in the year, Tess de Quincey will present Framed, a new instalment in her acclaimed “embrace” series.

In spite of the increasing number of high calibre artists seeking out FORM as presenting partner, the fragility of the organisation’s funding situation is an ongoing concern for its current director, Annette McLernon. She explains: “FORM’s core funding is very secure. We have just received triennial funding (2012-2014) from Arts NSW and Riverside Theatres is a key partner. However, the project funding for the Dance Bites presentations is less certain as the producers or individual independent choreographers are still very dependent on successful funding to develop and present their works.”

However, FORM does not only present work, it also offers a significant education program. Its various initiatives include master classes for young choreographers from Western Sydney and the popular Learn the Repertoire, See the Show series, as part of which presenting artists teach workshops and offer post show discussions.

campbelltown arts centre

Lizzie Thomson, PANTO

photo Heidrun Löhr

Lizzie Thomson, PANTO

In the wake of the redevelopment of Campbelltown Arts Centre (CAC) into a multi-arts centre, Lisa Havilah, its director 2005-2010, put a five-year strategic plan into action that included dance alongside visual arts, theatre, new music and live art/performance. For the first couple of years, dance at CAC was mainly presented in the form of individual projects. This changed when Emma Saunders was appointed as dance curator in late 2008. She was given the brief to develop a three-year framework for a Contemporary Dance Program and curate artists as part of it. Saunders, a well-respected member of the NSW independent dance community, best known for her work with the irrepressible dance trio The Fondue Set, rose to the challenge and put a multi-strand model in place which combined long-term development projects and residencies for local and international artists with the presentation of new work, both full-length pieces and short work commissions. Saunders says about her curatorial approach, “The CAC Contemporary Dance Program promotes interdisciplinary and intercultural projects. We support artists interested in questions around process, form and community engagement.” As a prime example Saunders cites the work of dance artist Lizzie Thomson who collaborated with an ensemble of community participants drawn from local amateur dance and theatre companies during her 2010 residency and then featured them in the finished work, Panto (see RT105), the following year.

Now in its fourth year, CAC’s 2012 dance program will culminate in a three-day festival project in October titled Oh! I Wanna Dance With Somebody. It will showcase outcomes from the program’s various strands and include 20 Australian and international artists as well as 150 Campbelltown locals across 15 projects, occupying the entire arts centre.

blacktown arts centre

Unlike Campbelltown Arts Centre with its variety of artform specific programs, Blacktown Arts Centre (BAC) runs a multidisciplinary contemporary arts program, of which dance is part. According to Kiri Morecombe, Acting Performing Arts Development Officer until recently, BAC is largely focussed on the development of new work from local and Western Sydney artists. In 2010, for example, Katy Green, a young performance practitioner born and raised in Western Sydney, was awarded a three-week residency as part of BAC’s performing arts program to explore cross-artform collaboration together with composer and sound artist Tom Hogan. A second stage development will take place at BAC in August this year.

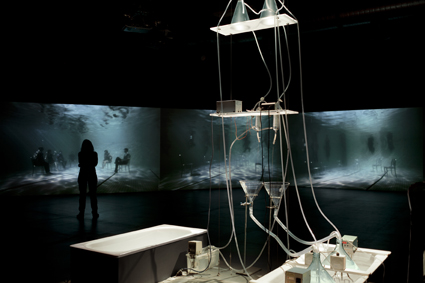

Another dance project recently supported by BAC was Megamaras by Indigenous dance artists Peta Strachan and Rayma Johnson, together with media artist Michelle Blakeney. Based on the story of Daringyule (dancing woman), who broke the law, and combining choreography with projected underwater imagery, the work was developed in residence at BAC in late 2011 and pitched at the Australian Performing Arts Market earlier this year. BAC has an Aboriginal Arts Development Officer, Andrea James.

Asked about the future of dance at Blacktown Arts Centre, Director Jenny Bisset, says, “With a stronger emphasis on dance in recent years, we have started to build an audience and expectation for this and will continue to look for new work through our performing arts residency program and our Aboriginal Arts program. We are particularly interested in hybrid work as we continue to build cross-disciplinary programming.”

youMove company

The Parramatta-based youMove Company was founded by dance artist Kay Armstrong in 2008, starting operations at the beginning of 2009. It is designed as a platform for emerging dancers and graduates. Even though strongly supported through a partnership with Western Sydney Dance Action, things didn’t go smoothly for Armstrong and her troupe initially, having missed out on funding during their first year. “The first year was about surviving basically,” Armstrong says. “The focus was on finding platforms for presentation, building our reputation and achieving industry credibility.” Gradually developing a repertoire of short works choreographed by herself and various independent choreographers such as Anton and Ian Colless, Armstrong worked tirelessly in the following years to raise public awareness for the company and create performance opportunities for her dancers. The company’s many gigs have included performances at the 2010 Under the Radar program (Brisbane Festival) and presenting work in a double bill with the Sydney Dance Company in Parramatta Park as part of the 2011 Sydney Festival. It didn’t take long until the company started to attract project funding and the business side of things consolidated. Last year the company incorporated and received program funding for the first time.

YouMove’s activities now comprise three strands: performance, mentorship and education. Of these strands, education is the most recent addition to the company’s program. It includes performance presentations and post-show workshops by the company for students (5-12 years) in Western Sydney schools. It’s an area Armstrong feels especially passionate about: “I’m a huge proponent of the idea of education being a transformative process. So what I’m hoping to do is to create and build future dance audiences. Now, the way to do that is to hit them young, you’ve got to get into the schools when they are at an impressionable age and give them really positive, expansive, unique, imaginative, inspiring dance experiences.”

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 2

© Martin del Amo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Matthew Day, Intermission

photo James Brown

Matthew Day, Intermission

THE FIRST TWO PARTS OF AN EVOLVING TRILOGY BY SELF-CHOREOGRAPHING DANCER MATTHEW DAY WILL SOON BE JOINED BY THE MUCH-ANTICIPATED THIRD WORK, INTERMISSION, AT THE PACT THEATRE IN SYDNEY. THOUSANDS AND CANNIBAL WERE AT ONCE CONTEMPLATIVE AND VISCERAL, MINIMALIST AND COMPLEX. I SPOKE WITH DAY ABOUT THE NEW WORK AND ITS RELATIONSHIP WITH ITS PARTNERS.

What was your motivation when you started out on the trilogy?

In Thousands (2010; see RT100 I was interested in stillness because I wanted to go back to something very simple, to what I was thinking of as the ‘degree zero’ of choreography because it was my first solo and I’d been reading Andre Lepecki and his writings on Nijinsky’s use of stillness. I was also interested in considering my position in dance history. So [it was] something about being still to allow other things to enter the space, for the audience to read the work in their own way—and also for other references to land on the body. Some of these I specifically choreographed into the work. There are Nijinsky references and then other things it’s up to the audience to project. But certainly it was about stillness or slow movement.

Steve Paxton is another reference and Vanessa Beecroft’s work—those models standing in galleries for long periods of time. It’s a bit different from Paxton but I thought, isn’t this interesting how there’s an unconscious choreography going on in the body.

When you say “unconscious choreography,” do you mean in the everyday or in stillness in dance?

My next project will be looking at the everyday. But I think in this series, the trilogy, they’re constructed theatrical settings. What I found looking at stillness was this vibration that’s happening without me producing it. What I’m doing is trying to be still. I try to think of this as the surface of the choreography or my intentional or conscious choreography as a score about stillness and how I do that.

That stillness is, I think, still evident in Cannibal (2011; see RT 102) although you’re moving in quite a large circuit. It’s still slow and there’s a sense of vibration.

The vibration that came up from underneath the stillness is what I consider the unconscious choreography, just in the sense that I’m not actively producing it.

Is that because, for instance, in the starting position of Thousands, you’re putting your body in a fairly stressful position?

The whole thing is stressful but I’m not interested in stress.

Is it more about intensity then?

Intensity. My objective with the piece is not to show any effort and to be as calm as I can be and not to fatigue. And the work should never look like I can’t continue. I’m not interested in failure or fatigue in that sense.

So they’re not endurance works?

They’re more about duration and what can happen if we just look at one thing for a long time and how something can change and how that reading of the same thing can change further if we sit with it for a long time. And I think this also came about by watching dance, where I feel like the dancers have just had a big shot of adrenaline backstage, run onto the stage and just go like move, move, move, go, go, go, counting to the count. Not that all dance does this any more. So it was really me challenging myself to make a choreographic work and not just dance, because that’s what I’d been trained to do and that’s what I love doing. So I got really excited about this vibrational quality.

It’s interesting that you made an observation about the stillness of Cannibal because while I was working on this, I started to think about the difference between the works. In Thousands I feel like I’m working very fast on a conscious level to refresh my attention and my perception. It’s happening very slowly and, to keep it alive, I need to work very fast, whereas with Cannibal, because there’s quite a lot of movement I drop into a much calmer place internally. Maybe that’s what you’re talking about.

The third part of the trilogy, what’s that springing from?

On the last day of Cannibal I had two performances to do and I’d done 10 shows altogether and it’s quite stressful to do twice in one day—or so I thought. But on the very last performance on the last day, I said to myself before I started, “Just take as much time as you need. This one’s for you. Find out what you can about the work. Do it and get what you can because this is the last chance you’ll have for a while.” And, while I was performing I started to discover a wave in the vibration. It’s just a very simple thing about the weight shifting between the right and the left foot, the transference of weight across the body and across space—the eternal wave that’s present underneath that. Waves are a pretty basic physical property and I just started to realise that it was present. It’s a feeling. So that kind of indentified that this would be the next thing. This is the future. The works each revealed themselves in different ways.

Thousands and Cannibal are both very sculptural, but Thousands is almost on a fixed point while Cannibal has a circuit and the works correlate with very different stage design and deployment of sound. In what way have you approached Intermission?

It’s a really good distinction you’re making—the movement’s relationship to pathways in space. I feel like maybe what I do is, I think about a wave—and it’s very naive the way I work. I just say okay, you’re going to do waves in the body for 10 minutes and see what happens and then I do it and I think this bit was interesting, or this happened. So I’ll do it again and maybe notice it again and just keep working. I’m realising this is not the way everyone works. I just do the piece when I rehearse. I just do the thing for about as long as I can. I do it for 30, 40 minutes and, okay, that’s what the thing is today. And then I slowly shape it over time.

I work with duration, which is the way I need to because it’s very hard for me to work on, say, a section. I think maybe the way a lot of people work is on sections: ‘I’m interested in this leg thing or this image here’ and maybe they look at ways of composing the order of these things. But when it comes to really making choreography and composing the thing, it happens as I’m doing it in the time that I’m doing it—performing the wave and seeing how it talks to me.

And in that process do you discover the space that you will occupy?

Yes. At first I start working just physically on, say, a wave and don’t worry too much where it goes in space. Then there’s a point where the pathway becomes the important thing that then determines the movement. So there’s this back and forth relationship. For example, I’ve had two main development periods and in the first I didn’t really think about the spatial map until the last couple of days and then started playing with something, mainly because I was having a showing. Then I had the Culture Lab residency [at Melbourne City Council’s Arts House] for two weeks and I kept that map and I said, okay, this is the map, how can I explore this as much as possible. Now I’m about to go back into the PACT Theatre [in Sydney where Day performed Thousands and Cannibal] and I’m actually going to question the pathway in space because I know more about the wave by articulating a pathway. Now it’s time to find out, to do it in reverse. There’s this constant negotiation between the pathway in space and the movement itself. In some ways they’re quite separate things.

There’s a design element that seems quite integral to your work. When do you start thinking about how you’ll create that space beyond the body?

Quite early I think but I don’t make decisions till quite late. With Thousands it was very pragmatic: I’ll make a piece with one spotlight and a backing track. That’s about touring the work; it’s about sustainability; it’s about keeping things simple; it’s about wanting the work to exist on its own terms choreographically. But these are also design principles: It’s also about minimalism. When I first did Thousands, it was in Northcote Town Hall, which has a massive gold velvet curtain. So I think of Thousands as a gold piece even though when it was shown at PACT, where you saw it, it was against a black wall. I wear gold sneakers. When it was at Dance Massive, it ended up looking quite orange.

So, what’s the future of the trilogy in terms of design. Cannibal is very white—floor, walls, outfit, your hair.

I’m trying to get white curtains made for Cannibal. So, they are in a sense an inversion of the usual black curtains of a space. Then the idea is that I can just request white tarket and chuck the white curtains in a normal touring suitcase. If that’s possible, then the future of Cannibal is quite open. And the thing is in Europe there are lots of white spaces anyway. As for the future of the trilogy, I’m going to present Thousands again in Melbourne in October and Cannibal in November and, hopefully, Intermission at Dance Massive in 2013. So this will be the first time that they’ll all be done within a five-month period and I think that’ll teach me a bit more about what it’s like to perform them back to back. The idea would be that they would be programmed across three nights. It’s impossible to do them all in one night and I don’t think it’s desirable either. They can tour as a trilogy across three nights so that each work has its own independence.

Why the title “Intermission”?

Intermission is about always being in the middle: never being here or there, never arriving completely, always being in a state of in-betweenness or becoming. It also problematises the idea of linearity. What is the order of these works? Even though we started out talking about how one work seeds the next, I found out things about Thousands by performing Cannibal. The works start to speak to each other in different ways. There are structural things I’ve discovered in Intermission that I’m going to retroactively apply to the other works. So they start to have this non-linear discussion with each other, which I find exciting.

The reason I liked the title was that I had this idea. We go and see a show and I was thinking of one of these big old amazing pros arch theatres. Everyone’s in there for the first half of the concert or ballet. And then everyone leaves. They’re outside drinking champagne or whatever in the foyer. And I just had this sense of what happens in the theatre in that intermission when no one is there. I like this idea of the life of the theatre without an audience, this in-between moment. What is the energy of this space at this moment? That’s what I’m interested in, that invisibility, the silent thing that you don’t actually see. That suspended moment of energy and stillness.

Matthew Day, Intermission, PACT Theatre, Sydney, June 19-30; http://www.pact.net.au/

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 3

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Yumi Umiumare, EnTrance

photo Heidrun Löhr

Yumi Umiumare, EnTrance

YUMI UMIUMARE DANGLES US WITHIN INNER AND OUTER WORLDS. HER BODY MEDIATES A UNIQUE COLLISION OF MOVEMENT STYLES, WHILE HER WORDS AND TEARS INVITE US TO REFLECT IN THE FACE OF OUR BEING, “I SWALLOW MY MIRROR WHILE I’M WATCHING MYSELF.”

EnTrance does not merely ask us to observe energetic transformations through word, rhythm, ritual and symbol; it navigates us through hyperbolic worlds that are indeed nothing other than who we are. Emotion, memory, everyday mediations and constructions, life, birth, death, spirit and love: EnTrance brings us home to ourselves.

Umiumare’s opening movement vocabulary is a heavy, slow shuffle; her head is tilted upward, oriented toward something in the distance. She seems to bear a cumbersome weight—a story involving a cat, a dusty window and the loss of her fingertips into a garden with a fountain that explodes with feathers of rich colour. The stage fills with projection, rolling out a bustling metropolis, all reds, yellows and blues. Umiumare absorbs the street rhythms like a blank canvas. We see it on her dress. Her dance is a strange mix of ‘go-go traffic conducting,’ forearms hinged at the elbows creating vectorial variations to wave the world in, and air-like pistons pumping the forces around. This pattern is punctuated by reverse star-jumps, arms straightened like bolts into a horizontal crossbar. Her martial stance complements five, six-foot-high erect masts, sails tethered at the waist. The image is positively nautical. Untethered, single threads fall outward to form a broken surface the width of the stage, a versatile design by installation artist Naomi Ota that metaphorises fragility, malleability and unpredictability.

Bambang Nurcahyadi augments each vignette with large-scale visuals, projecting scenic and urban backdrops and swirling, animated Umiumares, replicated in various guises on the screens. In one scene, the dancer, dressed in a black leather jacket covered with flashing thorns of tiny embedded LEDs (design David Anderson), thrashes about in concert with obnoxiously loud post-punk noise—guitar pedals of assault—and picks up a large LCD screen to use as a face mask. The image is a portrait of her inner Avatar, scratched and irritated by the superfluity of a hyper-existence.

Drifting into a different rhythm, Japanese characters cascade delicately down the threads spilling onto an umbrella held by Umiumare, now looking like a bleached-white Mary Poppins. She weathers the words in patient reprieve. We too wait, soothed, suspended, somewhat transported.

Umiumare tells us that in Japanese there are different names for different tears. Each type, or mode of crying, is named after the sound that the crier makes, an onomatopoeic nomenclature. “Cachuckachuck, cachuckachuck”, the crumpled wail of a woman who has lost her child. Tears like rain soak the cheek. I am reminded of a scene from Michael Haneke’s The Time of The Wolf where a mother weeps inconsolably at the death of her son. Sounds of soaking.

Umiumare emerges like a fake plastic flower to entertain us with a love song, singing off-key. We giggle along with this awkward serenade. When it ends we are plunged deeper into her primordial wail. She transmits something not belonging to her, something more universal; there is deep silence in the sonority of grief.

A bird of paradise, Umiumare engages with the ritual and dress of her traditions. A transcendent phase, almost ecclesiastic, she raises her arms, a stole of red and gold draped symmetrically over her arms. I think of the fountain and the cat that ate her fingertips. All images, words and sounds that formed disparate episodes momentarily speak one language. I am home.

Tangled in threads, Umiumare paints her body white with aggressive brush strokes. This final costume change shatters the coherency of two-dimensional image, each screen torn down by this monster of chaos. She stirs the space. Medusa. Her feet rooted, the base of her tongue driven from pelvic depths, viscera like magma ready to overflow. Her body is gnarled at the joints like an ancient tree still growing. Nothing more present than presence itself. Beneath the hypnotic birdcalls, drums and didgeridoo, the sorceress licks with flickering tongue those fingertips. Her eyes unnaturally wide, each a window open for all to see, each an opaque window reflecting back. Transformation.

For the most part I felt overwhelmed by the excessive mélange of cultural influences, aesthetic choices and movement styles. But by the end, experienced an unmooring of something indescribable, a deeper unitary movement that for me is a rare occurrence in performance. Entranced.

Performance Space, Dimension Crossing: EnTrance, performer, creator Yumi Umiumare, collaborator Moira Finucane, costume designer David Anderson, lighting designer Kerry Ireland, sound designer Ian Kitney, media artist Bambang Nurcahyadi, installation artist Naomi Ota; Performance Space, Carriageworks, Sydney, April 18-21

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 5

© Jodie McNeilly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Victoria Hunt, Copper Promises: Hinemihi Haka

photo Heidrun Löhr

Victoria Hunt, Copper Promises: Hinemihi Haka

VICTORIA HUNT’S COPPER PROMISES: HINEMIHI HAKA IS A ‘THEN’ MADE ‘NOW,’ A PAST CONJURED IN A PRESENT THAT WALKS THROUGH PORTALS INTO ONGOINGNESS. IT IS EPISODIC, WITH EACH ACT DETERMINED BY DISTINCTIVE BUT MUTATING LIGHTING STATES THAT ARE BOTH SHARPLY AESTHETIC AND THICKLY ATMOSPHERIC, AND BY AUTOCONVOLUTED SOUND THAT SPEAKS, SHATTERS, RUMBLES, ROARS, GRATES, GRINDS AND TRICKLES.

At the same time Hunt’s body moves amidst light and sound as one of these elementals; sometimes swept along or drawn by light, sometimes tortured by compacted screeches, possessed of sound. But at other times it is her moving body that controls the skies.

Copper Promises: Hinemihi Haka is a condensation of Hunt’s journey back into her Maori ancestry. [Hinemihi is a female ancestor and a ceremonial house connected with Hunt’s cultural heritage. Eds] It is a lament of alienation and a celebration of repatriation. It is a finding, a gathering, a travelling, a wandering and a landing. It is a work built over “a decade of embodied research across three countries…collecting video imagery, recording sound and interviews and making a series of short dance works” (program notes).

So those voices and actions and images that elude specific understanding are still understood: clarity is born of heartfelt and rigorous research, stretching out across continents and generations and coming back to a body. Victoria Hunt’s body as the human centre of Copper Promises becomes a place, reconciling the apparent conundrum of a cultural emphasis on “collectivity” and “community” (program notes) with this very solo work by dancing with ancestors and giving voice to ghosts which hang behind and around Hunt’s fleshy contortions.

There were so many resonant moments: like the dust cloud that seemed at first like smoke but had the shape of a figure, haunting on invitation, or the ghostly bride who pads solemnly soft along an aisle of white, her hair gently steaming. But two crescendos screamed louder than them all.

After another train has rattled past Carriageworks’ Track 8, after the slow lateral stalking of the stage by a nearly invisible body with only half a face, after the ghosts have whispered softly then echoed loudly on top of rumbles that gently shake space, after Hinemihi body has pushed itself into becoming rock, metal and rubber, after this molten non-body has bent, opened, twisted and sunk, Hunt, her skin glistening with sweat, spits gorgeous globules of beautiful saliva into the air and her hands become ‘pois’ (Maori performative devices which are swung by hand. Eds) that flick and twitch into a madness-trapped claustrophobia in a sharp white box of asylum light hanging in a sea of black, until a cloudy sky greyness drifts her and her madness into near invisibility again.

Later. After disappearing into a chasm of nothingness, Hunt’s chin and mouth appear, tattooed and moving. Her mouth and the mouths of the soundtrack speak in strangled distortions that are electronic and ancient, now and then. Hunt is a mask made by light, speaking in tongues with the rhythms of sharpening breath and dog screams, a sonic mountain of intolerable cruelty that hurts with its disturbing and frantic energy. Then, it is gone.

Afterward, it took some time to leave the silences and roars of Copper Promises behind. The past had taken hold of the present, so the world became liminal, a neither here nor there, a then and a now.

–

Performance Space, Dimension Crossing: Copper Promises: Hinemihi Haka, concept, choreography, dance Victoria Hunt, lighting Clytie Smith, sound James Brown, producer Fiona Winning, Performance Space, Carriageworks, Sydney, May 4-12

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 6

© Pauline Manley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

l-r Ninian Donald, Veronica Shum, Tim Rodgers, Jessica Statton, Involuntary

photo Sam Oster

l-r Ninian Donald, Veronica Shum, Tim Rodgers, Jessica Statton, Involuntary

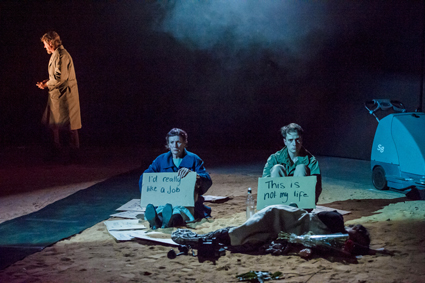

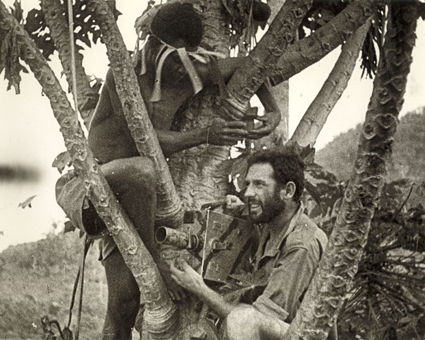

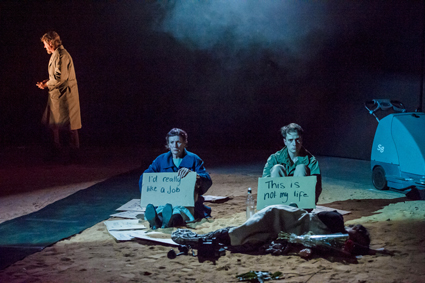

KATRINA LAZAROFF’S INVOLUNTARY SPEAKS OF HOW WE ARE ORDERED AND SHAPED THROUGH THE VARIOUS MECHANISMS OF COMMUNICATION WE ENCOUNTER OR USE, BEGINNING, TONGUE IN CHEEK, WITH PROJECTED TERMS AND CONDITIONS FOR THIS PERFORMANCE. THESE BECOME MORE AND MORE ABSURD AS THEY ARE SCROLLED THROUGH.

An extended dance sequence, clearly drawn from an investigation of involuntary movements, follows with toe-tapping music. The dancers are then asked a series of questions. They are clearly under duress, the suggestion being that they need to pass some test. They bend and twist in response.

The great appeal in Lazaroff’s dance projects lies in the humour that informs each performance and her determination that the dancers appear as ‘regular people.’ These two aesthetic choices are not unrelated. In Involuntary she borrows from clowning to achieve the various vignettes and the performers also frequently address the audience directly. Four ladders are used to great effect. Climbing up a ladder becomes a clown routine of entanglement because of the obstacles presented by ‘the OH&S supervisor.’ A dance routine is made from spectator behaviour, what we do in the privacy of lounge room television watching. We also watch the dancers on Skype—private projections of self—talking, gaming, masturbating.

Two dancers have a conversation via computer in text language. This is shown to be a little limiting. They also meet up via video on their mobile phones—a fairytale image as these two tiny screens dance together to music box tinkling. Always we see the struggle for the individual to squeeze into narrowly determined situations and behaviour, longing to break free of constraint, as exemplified beautifully by an office chair routine that starts with listening to a telephone answering service and becomes a ballet of flight as the dancers give up waiting. The performers are equal to this task—engaging to watch, physically skilled and bold.

The knock-about humour, easy polemic and engagement with the audience reminded me of the Aussie performance aesthetic championed and immortalised by Circus Oz. At one stage the dancers compete for air time to tell us their complaints. An audience member is then invited on stage with the performers to speak of what infuriates them.

The technology is used skillfully. The witty projections are seamlessly and elegantly woven into each vignette. The music is fun. The dance material in solos, duets and quartets captures the awkwardness of being not quite in control of one’s body. The final duet is a simple homage to touch and connection as performed by two dancers, though the true message of this piece, and of interaction with technology as a disciplinary force, is ‘be playful.’

One Point 618 & Adelaide Festival Centre: Involuntary, director, choreographer Katrina Lazaroff, performers, creators Tim Rodgers, Ninian Donald, Veronica Shum, Jessica Statton, lighting, projection design Nic Mollison, sound design Sascha Budimski, set design Richard Seidel; Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, May 1-5

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 6

© Anne Thompson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Pari passu…touch, Leigh Warren & Dancers

photo Tony Lewis

Pari passu…touch, Leigh Warren & Dancers

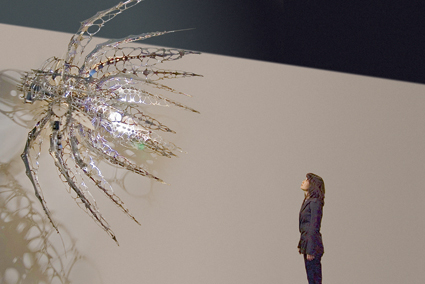

PARI PASSU…TOUCH IS AN INTRICATE WEAVE. IT TAKES PLACE WITHIN AN EXQUISITE MARY MOORE DESIGN—A PERFECTLY CIRCULAR WHITE FLOOR WITH TWO WAVE FORM SCREENS OF DIFFERENT LENGTHS POSITIONED NEAR THE BACK OF THE CIRCLE AND SEPARATED BY A GAP. THE WORK BEGINS WITH A LIGHT GLANCING ACROSS THE SCREENS REPEATEDLY, REVEALING THE TEXTURE OF WHAT COULD BE THE MOSAIC OF ROCK ON A SHORELINE.

The lights dim and solid becomes fluid, rock becomes mud. A distant shadowy figure walks towards us, a projection, but then a live male body takes over. The dancers are initially figures behind, appearing to be in the wall—the work presents mutability as order. The screens are revealed to be touch screens. The dancers emerge from behind the wall and return there throughout the piece. The surface changes throughout with beautifully selected projections by Adam Synott. Sometimes the surface shifts in response to the dancers—patterns scatter or collect.

Though the media technology is part of the ‘here and now,’ the references that haunt the work are of some ancient time. My mind wandered to cave paintings and tribal rituals. Some version of our past lurked as a referent. The sound shifted between wind instruments, strings and drums as the dancing changed rhythm and dynamic. Though touch was the declared focus, the dancing away from the screen/wall was a relentless, almost restless, articulation of body in confined space, body in relation to floor and body in relation to other bodies. The dancers performed solos, duets and unison quartets.

Behind/in the wall the movement slowed, opened out, changed shape. The dimensions of the space and wall made the dancers appear larger than life, godlike. At a certain point I was struck by the thought that a cosmology was being represented. I looked up and the lighting bars were in arcs; the heavens appeared. At another point an orange glow dominated the stage, that unmistakable orange that has come to represent Australia. I am struggling to describe the intricate unsettling of solidity, of surface, of depth of field, of time, of symbols and cultural positioning in this dance (Warren has had a long commitment to supporting and working with Indigenous dancers and choreographers).

The duets were a case in point, involving a knotting and unknotting of bodies. There was not the usual rhythm of separation and coming together that often marks this duet form. In the quartet a simple walking forward and back in unison and also the detail of the shoulders and upper backs moving on four hunched dancers was profoundly moving. They were working at the edge of their ability to stay accurate and present. This was thrilling. I found it tantalising to watch a work where referents hovered but had been relegated to the outskirts; where I focused instead on patterns in process and the feelings and meanings these generated. I was reminded of my pleasure in watching Lucinda Childs’ dancers stepping along geometric spatial pathways swinging their arms in the 1980s and was glad of this Australian dance project.

Leigh Warren & Dancers, Pari passu…touch, artistic director, choreographer Leigh Warren, dancers Lisa Griffiths, Bec Jones, Tim Farrar, Jesse Martin, set design Mary Moore, music composition, projection design Adam Synnott, lighting Benjamin Cisterne, garments Alistair Trung, Space Theatre, Adelaide Festival Centre, May 17-26

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 8

© Anne Thompson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

More or Less Concrete, Tim Darbyshire

photo Ponch Hawkes

More or Less Concrete, Tim Darbyshire

HUMANS ARE SENSATES, THERE IS NO OTHER WAY TO PERCEIVE THE WORLD OUTSIDE THE BODY. ACCORDING TO ANTHROPOLOGISTS, MEMORY IS THE HISTORY BOOK OF OUR SENSORY EXPERIENCES WHERE WE STORE AND RESTORE EACH SENSORY DIMENSION WITHIN THE OTHER, MAKING IT DIFFICULT TO SEPARATE AND VERBALISE OUR SENSATIONS. TIM DARBYSHIRE’S COLLABORATIVE PERFORMANCE IS BASED ON THEORIES OF SYNAESTHESIA, SENSORY EXPERIENCE AND MEMORY.

In More or Less Concrete, the audience witnesses a kind of abstraction of the body and its movements. The slow, dreamy pace makes this as much a study in sculptural forms as dance. Through sensory-challenging sound and lighting, it is also a retelling of these snatches of memory through performance.

In a darkened theatre, headsets deliver the minimalist and hypnotic sound. A car in the distance, a creaking chair, a metal street sign in the wind? The recordings are central to the piece, as in the dance itself they explore the intersection of sound and movement of artificial or natural environments. Microphones near the stage pick up the sound of limbs slapping the stage, heads knocking on the wooden stage and the breath and grunts of the performers. The containment and editing of sound through headphones coupled with darkness heightens our visual perception.

Three performers in boiler suits appear in a haze of low watt blue light, their heads tucked away out of sight. Without the visual reference point of heads, the performers appear to be disembodied sculptures. For much of the performance, faces are hidden, giving the performers an anonymous, inhuman nature. The unfamiliar positions of the bodies—such as upside down torsos—leave behind unrecognisable, twisted forms, like the casts of animals made at Vesuvius or Richard Goodwin’s concrete sculptures of cast bodies, Mobius Sea. The title of the performance refers to the shifts between the concrete reality and the more ephemeral forms of bodies. Movement transforms the body from recognisable states as human or animal, to something more abstract, to machine or ‘other.’

Darbyshire’s work is informed by visual art and film—initially the frequent pausing in the choreography allows for the same contemplation as visual art. Then there are the filmic qualities. We are warned in advance about loud noises—after a somnolent start there is a sudden bang, the kind that keeps you on the edge of your seat during a thriller. In a dark, controlled sensory environment this keeps the audience alert and tense.

A former star swimmer, Darbyshire evokes memories of swimming through the colour blue—the effect is immersive and cold, much like blue tint in film. We see the bodies as if underwater, with oscillating arms. The forms the body makes when suspended in water are strange yet recognisable. There are other playful impressions from childhood: sprinklers and the swooshing, claustrophobic brushes of a car wash.

More or Less Concrete is a quietly unsettling and revelatory investigation into the crossroads of our senses. We walk away having experienced bodies as abstract forms while movement is perceived sonically as well as visually.

More or Less Concrete, choreographer, director Tim Darbyshire, performers Sophia Cowen, Tim Darbyshire, Matthew Day, sound designer Myles Mumford, lighting, production Bluebottle, dramaturg, sound theorist Thembi Soddell, Arts House, North Melbourne Town Hall, April 18–22

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 8

© Varia Karipoff; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Hard to be a God

photo Tony Lewis

Hard to be a God

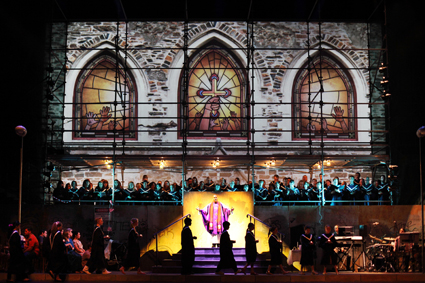

WE MEET AT THE CROSSROADS IN BOWDEN, A ONCE-INDUSTRIAL INNER SUBURB OF ADELAIDE, NOW UNDERGOING TOO-SLOW TRANSFORMATION. THE PERFORMANCE WILL TAKE PLACE IN A WAREHOUSE, A PRE-FAB COLORBOND ENCLOSURE, SLUNG UP TO HOUSE A BROAD CONCRETE SLAB. OUTSIDE, A FESTIVAL CROWD MILLS IN THE DUST.

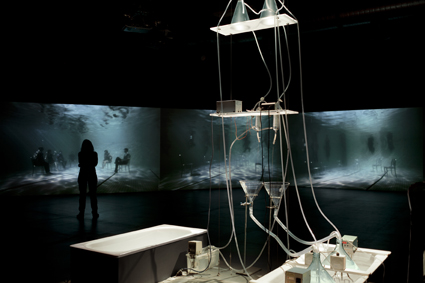

We are invited inside, as the show gets underway. Hard to be a God is performed off the back of two semi-trailer trucks. Set at right angles to each other, one truck is a platform for on-stage action, the other a screen for projections. The audience is seated, rather comfortably, in the rectangle between, on tiered banks of plastic chairs.

This is transient theatre with an interventionist feel. Its politics are transportable, the scenario universal. Hungarian director Kornél Mundroczó explains in the program: “this transitory situation is very familiar: being at someone’s mercy while being on the road illegally, fleeing from somewhere.” We are witness to their transit suspended: three young women, sewing jeans in a truck-top sweatshop, are kept busy by a bossy fourth, who enslaves them to their work, and trades them to the men for sex. The motley gang of men use the women, one after the other, to make porn in the other truck. We have been warned.

In this off-stage action—relayed by hand-held video camera, with live feeds projected onto screens—a naked woman screams as her back is scalded with hot water; another’s neck is broken, or so it seems, from too much rough handling; a third, now pregnant, struggles at the prospect of being buried alive. These pornographic scenes of sadistic violence are spliced into an on-stage flow depicting forced labour, industrial accidents, medical interventions—urine tests, an abortion. Violent sexuality mixes with lyrical solidarity. The characters sing and dance at times to alleviate the boredom, the degradation—and to cheer us up, it seems.

Mundroczó draws the moral dramaturgy of Hard to be a God from the sci-fi novel of the same name by the Russian brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. The novel lends a political sub-plot of extremism and extortion to the performance: a sister raped, a son turns on his politician father. It also lends a theological dimension: witnessing the cruelty of God’s creations, an angel-man exacts revenge on our behalf in a final splatter-act of retribution. The performance closes on an ethereal moving image of this angel-man, floating backwards in a boat along the wetlands of eastern Europe.

The performance also seeks to extend its moral reach with a retro-soundtrack of emotional devastation: Dire Straits’ “Brothers in Arms” accompanies the closing image; Gene Pitney’s “Something’s Gotten Hold of My Heart,” Burt Bacharach’s “What the World Needs Now” and the Pop-Tops pan-European hit “Mamy Blue” momentarily elevate our interest and sketch the contours of hope. At other times, the look and feel of the performance is grimly realistic, desperate and fatalistic. The sweatshop set is meticulous in its clutter, greasy with machinery, with steaming racks of clothing and factory waste. It is work-wear, industrial protection and trade tools for the men; stretch-knits, tracksuits, underwear and nudity for the women.

The production’s mediation of off-stage sexual violence is realistic, but somewhat numbing in effect. The day after, I felt flat. Like surgery under local anaesthetic, I could see violence inflicted but I didn’t feel the pain. For me the moment of greatest agitation was a disturbance in the audience half-way through. The lights came up, the stage manager intervened, and a couple walked out, before one of the actors sought our permission to continue. At first, I thought they were a plant: an act of staged objection to highlight our inaction. And then I wondered nervously: were they actually offended? But no. Next morning, in an email, the festival’s senior publicist sought to reassure us with innocuous affect: “the audience member who was unwell last night has a pre-existing medical condition. He recovered quickly and apparently this happens to him regularly.”

Isabelle Hupert, Florence Thomassin, A Streetcar

photo Shane Reid

Isabelle Hupert, Florence Thomassin, A Streetcar

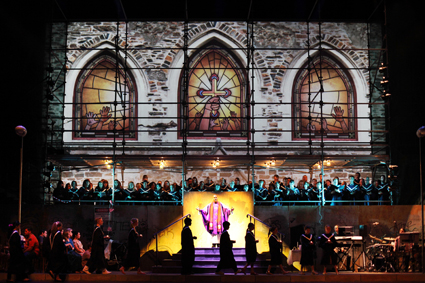

A Streetcar from Odéon Théâtre de L’Europe seems likewise premised on assumptions about anaesthesia and the audience. Director Krzysztof Warlikowski overcomes the intimate stage realism of Tennessee Williams’ play with a production of grand expanse, hard surfaces and voluble performances.

The performance opens at Adelaide’s largest theatre with actor Isabelle Huppert as Blanche Dubois babbling behind glass. She is encased in an elevated bathroom-hallway that extends horizontally across the stage, rolls on tracks in the stage like a streetcar, and is glazed with ‘electronic privacy glass’—ceiling-to-floor plate-glass panels that switch between transparent and opaque. In opaque mode, they serve as screens for video projection of live action, black-and-white in evocation of Elia Kazan’s 1951 film.

What I feel foremost of this performance is the smoothness of its surface. The main area of the stage is a suite of ten-pin bowling alleys that reach into its depth. Yet when Huppert descends onto the stage my depth perception is at a loss. The emotional volatility of Blanche’s intervention between Stella and Stanley (played by Florence Thomassin and Andrzej Chyra) is flattened by the monophonic consistency of the actors’ voices. As in music theatre, they wear microphones to amplify their voices. The disarticulation of actors’ voices from the spatiality of their presence makes me feel like I have lost my sense of touch. It is as if the entire performance were playing out behind glass.

Warlikowski’s direction seems driven to overcome the prospect of an audience at a distance from the actors, cut-off and out-of-touch. Tiny interactions and minute gestures are retrieved by video from inaccessible spaces—in the bathroom, under the bed, beside the couch—and magnified with projection to amplify their presence on such an expansive stage. Transformations in the actors’ portrayals of their characters’ emotional trajectories are ‘telegraphed’ with an intricate plot of wig and costume changes.

Transformations in the dramaturgy of minor characters amplify the psychic theatricality of Blanche’s plight. Her homosexual husband—”un jeune homme” played in grand-guignol style by Cristián Soto—is brought back from the dead to dance the tango on stage with Mitch (Yann Collette). The role of Eunice, Stella’s friendly upstairs neighbour, is enlarged by Renate Jett into singer-interlocutor—belting out Pulp’s “Common People,” Eric Carmen’s “All By Myself” and other songs, juxtaposing key moments with the delivery of inter-texts (from Oedipus, apparently, from Wilde, Flaubert and Dumas), and stepping into the audience at the interval for some light-hearted banter about love, romance and relationships.

Warlikowski’s directorial strategy is multi-channel amplification, blasting through the script to expose the theatricality of the psycho-sexual on an operatic stage. I make contact with the work. But was this contact premised on an assumption that I wouldn’t? That without the amplifiers, I’d feel nothing?

By comparison, Gardenia from Alain Platel and Frank van Laecke of Les Ballets C de la B transacts a simple encounter with its audience. Nine elderly people of transitive genders, a ‘young guy’ and a ‘real woman.’ Wearing suits, they each undress revealing the frocks they wear beneath.

One tells jokes, one sings, another reminisces. They address the audience directly. They mince and pose and pout as an ensemble. They don wigs, slap on make-up, slip on heels. They swing handbags to Ravel’s Bolero and mime the words to songs. They spread red carpet on a parquet floor. They walk.

As a performance, Gardenia is not much more than that. “The journey is so dear to us,” advise Platel and van Laecke. “We advance without hurrying.” The show unfolds at walking pace. There is no assumption that I feel nothing. And no demand that I feel more.

2012 Adelaide International Arts Festival: Hard to be a God, director Kornél Mundroczó, Old Clipsal Site, Bowden, March 8-14; A Streetcar, based on A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, director Krzysztof Warlikowski, Odéon-Théâtre de L’Europe, Festival Theatre, March 14-17; Gardenia, directors Alain Platel, Frank van Laecke, Les Ballets C de la B, Dunstan Playhouse, March 2-5

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 10

© Jonathan Bollen; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

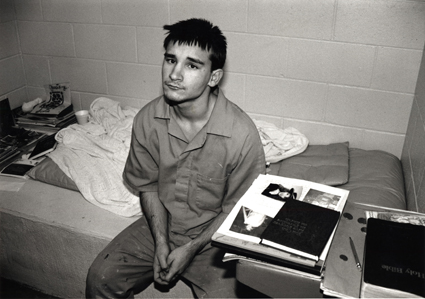

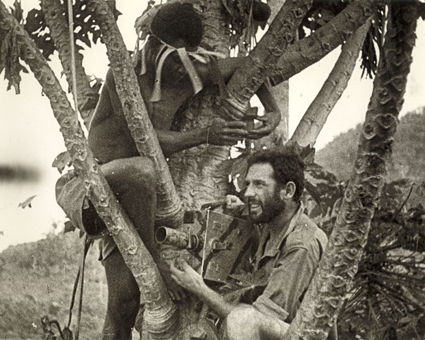

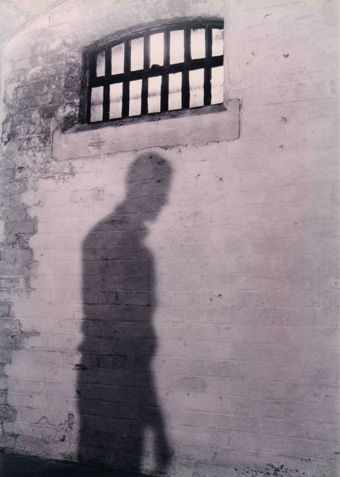

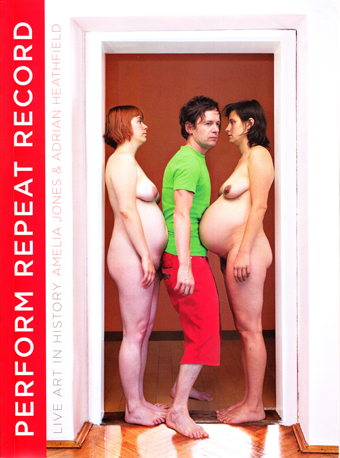

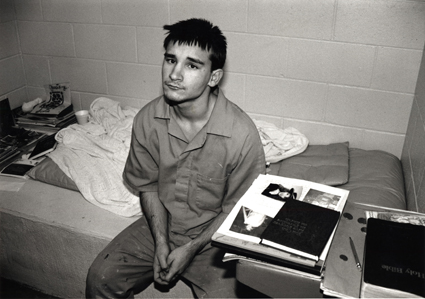

Jessie Misskelley Jr, Paradise Lost 2: Revelations

AMERICAN CINEMA IS SO RIFE WITH STORIES OF THE WRONGLY ACCUSED YOU COULD BE FORGIVEN FOR THINKING THE UNITED STATES SPECIALISES IN EPIC MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE. OR PERHAPS THE OPENNESS OF AMERICAN SOCIETY SIMPLY LENDS ITSELF TO THE EXPOSURE AND DRAMATISATION OF LEGAL ERRORS.

The recently completed documentary trilogy Paradise Lost, detailing the story of the West Memphis Three, certainly features some extraordinary access to courtrooms, but the result is a far from reassuring portrait of American justice.

Director Joe Berlinger unveiled the final part of the Paradise Lost trilogy in March at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI), leaving viewers with more questions than answers about this nightmarish case.

Berlinger recalls that when he and his filmmaking partner Bruce Sinofsky began shooting the first Paradise Lost film for HBO—The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996)—they thought they were documenting “an open and shut case.” The police claimed they had strong evidence implicating three local teenagers in a particularly horrific triple homicide in West Memphis, revealed when the mutilated bodies of three eight-year-old boys were found naked and hogtied beside a creek on May 6, 1993. Seventeen-year-old Jessie Misskelley Jr, 16-year-old Jason Baldwin and 18-year-old Damien Echols were quickly arrested and charged with the murders. Misskelly confessed to police about his involvement in the crime and implicated the other two.

It quickly became apparent to the filmmakers, however, that there was no physical evidence linking the teenagers to the murders. Jessie Misskelley Jr, who had an IQ of just 72, had been interrogated by police for 12 hours before making his confession. Only 46 minutes of the interview had been recorded. Despite the fact that Misskelley quickly recanted his statement, arguments in court that the confession was false and extracted under coercion were dismissed by the jury, and he was sentenced to life in prison.

In the separate trial of Echols and Baldwin, the prosecution argued the boys were members of a satanic cult and the murders part of a bloody ritual. The teenagers’ love of Metallica and Stephen King was introduced as “evidence” to support these claims. Each was found guilty on three counts of murder, and Baldwin was sentenced to life imprisonment. Echols was sentenced to death.

Amazingly, Berlinger and Sinofsky were permitted to film both trials, an experience Berlinger describes as “jaw-dropping.” Their lenses captured the flimsy prosecution case and the inept, scattershot approach of the boys’ defence lawyers. They also revealed the impassioned hatred felt by the parents of the murdered boys and the rumours of Satan worship that swirled around Memphis in the wake of the murders.

Half a decade later, Berlinger and Sinofsky returned to the case to make a second film entitled Revelations (2000). The first documentary engendered a storm of controversy about the trial proceedings and dubious nature of the prosecution’s case, but the second film revealed little conclusive new information about the murders and subsequent trials. The filmmakers were also denied access to courtrooms during various fruitless appeals. Instead, Berlinger and Sinofsky spent a lot of time with John Mark Byers, father of one of the victims; his deranged religious zealotry makes Robert Mitchum’s character in The Night of the Hunter look restrained.

Questions had already been raised about Byers in the first documentary after he bizarrely gave the film crew a knife as a present, which was later found to hold traces of human blood that matched the type of both Byers and his dead son. By the time of the second film, Byers’ wife had also died in mysterious circumstances. Various theories developed in Revelations imply Byers may have played a part in the murders, but at the end of the film a lie detector test suggests that he believes he is telling the truth when he denies any involvement. On the other hand, at the time of the test he was taking a cocktail of five mood-altering drugs, which may have skewed the result somewhat.

The recently completed third part of the trilogy, Purgatory (2011), avoids the sensationalist tone of the second instalment and traces developments that led to the release of the West Memphis Three in August 2011. The biggest shock is seeing the effect of time on the accused. Misskelley, a slight teenage boy in 1993, is now an overweight middle-aged man. Echols and Baldwin are in better shape, but they are similarly on the edge of middle-age and as the film opens, all three have spent more of their lives behind bars than living free.

The decisive development traced by Purgatory is the analysis of DNA from the crime scene, utilising technology not available at the time of the original trials. Tests find that none of the DNA material from the scene can be linked to the accused. Intriguingly, the tests do show that a hair on a shoelace used to tie up the victims may have belonged to the stepfather of one of the murdered boys.

After various protracted legal machinations the state offers the West Memphis Three a deal that will see them released, based on the time they have already served. The trio agree rather than endure a protracted retrial. In this sense the final part of Paradise Lost provides something of a resolution, but many questions are left hanging, not least the riddle of who really murdered the eight-year-old boys. The films suggest many possibilities, but in the end all the leads only serve to demonstrate just how slippery the notion of truth really is, whether it’s on screen or in the courtroom. Errol Morris’ celebrated The Thin Blue Line (1988) similarly showed up the mutability of supposedly factual evidence, but where Morris’ film basically detailed two conflicting versions of the same crime, the only certainty left by the end of Paradise Lost is the fact of the original murder. Director Joe Berlinger admitted at the ACMI screenings, for example, that much of the evidence presented in the second film implicating John Mark Byers has since been discounted, providing a sobering lesson in the power of cinema to lead viewers to conclusions that aren’t necessarily correct.

Most horrifyingly, however, the Paradise Lost films dramatise how three teenage lives were ruined based on the flimsiest of circumstantial evidence. Were it not for new DNA technology, one of the trio would almost certainly have been executed. Watching the legal saga play out over two decades and across three films, the entire process of ‘justice’ ends up looking almost as monstrous as the original crime.

Paradise Lost 1: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills; Paradise Lost 2: Revelations; Paradise Lost 3: Purgatory; directors and producers Joe Berlinger & Bruce Sinofsky; 1996, 2000, 2011; HBO; USA; screened at ACMI, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, March 1-4

RealTime issue #109 June-July 2012 pg. 14

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Golden Slumbers

NOW IN ITS 15TH YEAR, PERTH’S PREMIER FILM FESTIVAL SHOWS NO SIGNS OF SLOWING DOWN. FESTIVAL DIRECTOR JACK SARGEANT EXPLAINS HOW THE REV MANAGES TO COMBINE THEMATIC SOPHISTICATION WITH ITS RENOWNED YOUTHFUL SWAGGER.

As the festival’s July start date draws closer, Sargeant acknowledges that he is still under the gun, dealing with the staggering number of submissions that Revelation receives. “This year I’ve chased down three or four hundred movies,” he estimates. “And we get submitted I don’t know how many hundreds that Richard (Sowada, Revelation founder, now working at Melbourne’s ACMI) and I wade through. It’s pretty mammoth. Rev seems to grow exponentially each year—there’s just more and more happening.”

But while Sargeant eschews the notion of selecting films for the festival based on a preconceived overarching theme, he will concede that a dominant throughline does tend to form as choices are made and the pile of hopefuls is winnowed down. “It works out that we have got a theme this year,” he says. “Well, actually, there are two: community and family. But you don’t look for things—these things just start emerging.”

It’s a fitting theme. Revelation is, after all, one of the key events on the Western Australian film community calendar. Inaugurated in 1997 as a showcase for a handful of independent shorts, it now encompasses a program in excess of 100 films and attracts a large number of international guests. It could easily be argued that the notion of community is present every year, inasmuch as the festival acts as a hub for the Perth film scene.

Rev in 2012 boasts a notably strong documentary stream. “This year we’ve got a lot of documentaries,” Sargeant says. “I think 15 or 16 documentaries at this point. Documentaries are really on the ascendant. I don’t think we’ve seen any ‘Occupy’ documentaries, but we are seeing a shift away from environmental stuff to economic and political stuff coming in. I think we’re seeing a shift in film in that direction.”