Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

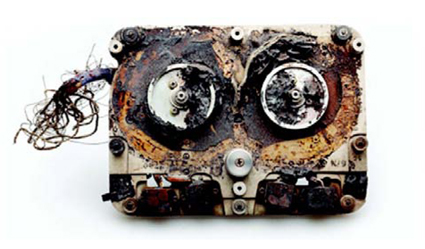

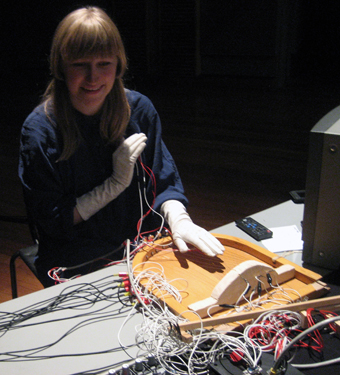

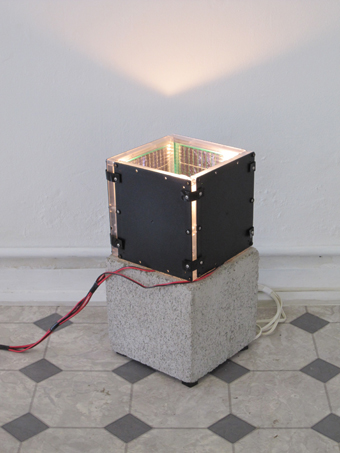

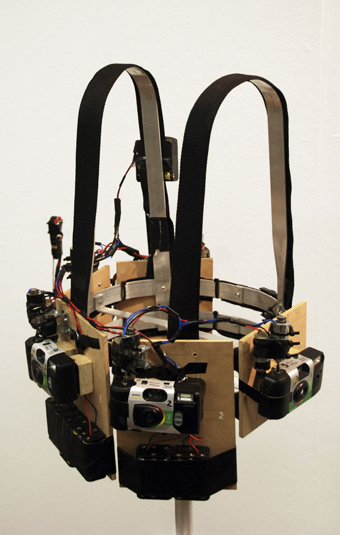

Emily Morandini, filet électronique

photo Kusum Normoyle

Emily Morandini, filet électronique

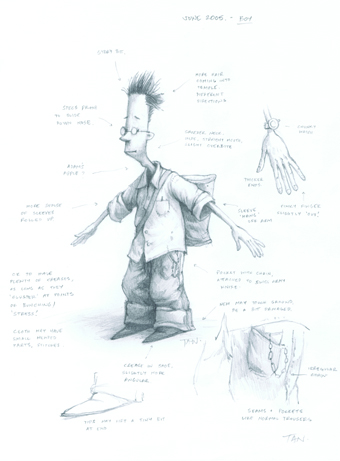

ON THE LEAFY FRINGE OF CAMPERDOWN PARK, I.C.A.N.’S (INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ART NEWTOWN) NEWEST SHOW ADDS A LAYER OF ANACHRONISM TO THEIR TRADEMARK INCONGRUITY. FILET ÉLECTRONIQUE/ISLAND IS A GENTEEL COLLECTION OF POST-SUBURBAN ARTEFACTS IN THE VERY URBAN FRINGE. A CONTEMPORARY SALON APOCALYPTICISM, OR SOME FUTURE ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECONSTRUCTION UNSTUCK IN TIME—WHATEVER… THIS SHOPFRONT STANDS OUT FROM THE BROWN AND IMPERTURBABLE LINE-UP OF DECENT LIFE LIKE MAD MAX IN CRINOLINE.

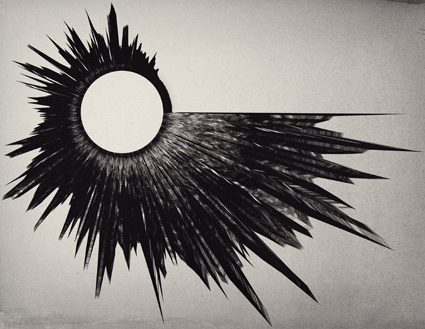

Emily Morandini’s piece is the filet électronique and has the virtue of a completely self-descriptive name. Round filet lace nets are threaded with copper needlework, punctuated at the ends by batteries and speakers, emitting a treble whine. Yep, networks, right angles, minute interconnected fibres—craft had ’em before mass electronics. Check, check and check. You remember the Hyperbolic Crochet Reef (created by Christine and Margaret Wertheim, http://crochetcoralreef.org) where dainty handicraft recalls raw nature? This is the yang to that yin, a stitched homage to circuitry over coral, courtly handicraft for the post-technological parlour.

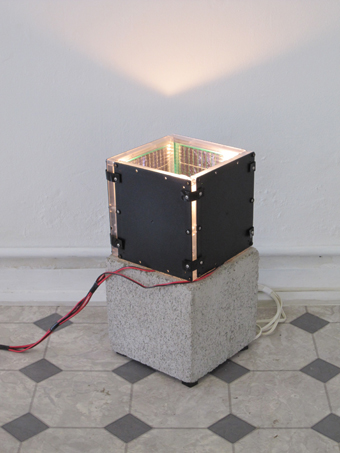

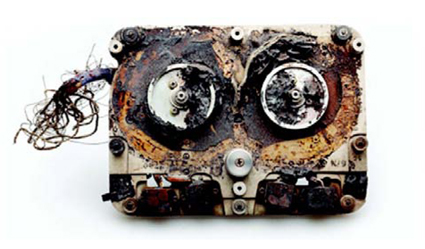

Peter Blamey, Island

photo Kusum Normoyle

Peter Blamey, Island

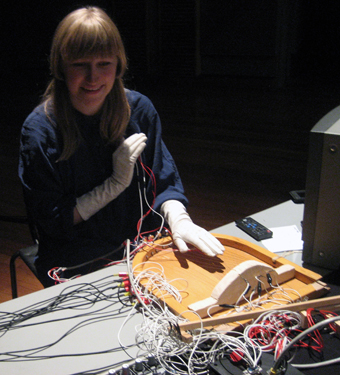

Two octaves below, Peter Blamey’s Island also hums, and occasionally squeals. This originates in a different future, long after the Anthropocene. It’s not needlepoint, or anything else from CRAFT magazine. Blamey liberates himself from the conventions of traditional handicraft by participating in the plastic, evolving genre of repurposing illegally dumped crap off the street.

A bouquet of found circuit boards opens leaf-wise, with machine-drilled pores and copper-etched capillaries. This is one part robotic Ikebana to two spontaneously generated silicon organisms. The surface is dusted with a faint fuzz of copper floss, moving in the air currents, and it squeals as you brush it, like an electric touch-me-not.

Peter Blamey, Island

photo Kusum Normoyle

Peter Blamey, Island

The piece itself is embedded in the flows of that neo-ecology—mineral waste digesting in the urban metabolism—its body scrap accretions of once-were appliances. This assemblage of motherboards and speakers is powered parodically and circuitously: electricity is derived from a solar panel lampshade which wraps around an incandescent light bulb, a ‘detrivore’ feeding off oil in a travesty of photosynthesis. Conductive cilia wave in the ambient radio fields, recycling electromagnetic waste into mindless warbling.

Where the connectivity in Morandini’s piece is punning, verbal and personal, Blamey’s work is direct, physical and inhuman, the waste fields of a million appliances made audible. The sound from those speakers is the unfiltered interference from the ad hoc antennae of the circuit-boards, performed it seems, for ears other than ours: the secret life of circuits, played out on an Earth after us.

Here are two sardonic takes on the DIY resurgence. Post-consumerist transposed into post-consumer in a world where DIY has been associated as often with fertiliser bombs as with handicraft; where survivalism and tree changing vie for fertile land; where going back to the land may lead you to an open-cut pit, or a strip mall, but you decide to stay there and till it yet.

Emily Morandini & Peter Blamey – filet électronique/island, ICAN, Sydney; July 22-Aug 7; http://interlaps-overlaces.tumblr.com/; http://icanart.wordpress.com/2011/07/19/july-2011-electronique-filet-island/

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© Dan MacKinlay; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Samantha Scott, Man Made Hybrid

courtesy the artist

Samantha Scott, Man Made Hybrid

we are what we eat

In Samantha Scott’s Man Made Hybrid, potatoes have eyes, actual eyes, and, uhhh… fins. Scott’s delicate and sometimes whimsical assemblages offer wry speculations on the possible ramifications of genetically modifying biology, exploring “the natural imperative of genetic information; the instructions that control how living things grow, develop and carry out life processes and survive (press release).” Scott’s exhibition is part of Craft Victoria’s Craft Cubed Festival 2011 themed HYBRID, offering a month long series of activities including exhibitions, professional development workshops, open studios, a market and an online portal. While you might have missed Adele Varcoe’s iFOLD technique in which she shapes human skin (still attached) into temporary garments, there’s still time to appreciate Tessa Blazey and Alexi Freeman’s Interstellar Gown made from 600 metres of gold plated chain. Man Made Hybrid, Samantha Scott, Aug 23-Sept 3, Heronswood, 105 Latrobe Parade, Dromana, Melbourne; http://craftvic.org.au/craft-cubed/satellite-events/exhibitions/man-made-hybrid; Craft Cubed Festival 2011, various venues across Melbourne, Aug 4-Sept 3; http://craftvic.org.au/craft-cubed

action fashion

public fitting, Mark Titmarsh, Todd Robinson. See Vimeo for full credits

Keeping up the fashion theme is Public Fitting at MOP Projects in Sydney, a collaboration between painter and video artist Mark Titmarsh and former fashion designer now artist Todd Robinson. In a live performance on the opening night, fashion and painting will literally collide in an action painting fashion catwalk free-for-all. The results will be exhibited as garments, videos and paintings exploring the intersection of the artists’ practices. Public Fitting, Mark Titmarsh, Todd Robinson, MOP Projects, Aug 18-Sept Chippendale, Sydney; www.mop.org.au/

Phoography, Max Lyandvert, George Poonkhin Khut & NIDA Production Students

courtesy the artist

Phoography, Max Lyandvert, George Poonkhin Khut & NIDA Production Students

brainwaves, soundwaves

Max Lyandvert, well known for his dark and haunting soundscapes for theatre, is currently artist-in-residence at NIDA courtesy of the Seaborn, Broughton & Walford Foundation. Collaborating with second year Properties, Costume and Production students Lyandvert has dreamt up the sound installation Phonography, which will inhabit the evocative environment of the Paddington Reservoirs with a “forest of hanging, waterlogged garments fed by currents that turn the clothes into speakers (press release).” The sounds of adjoining Oxford Street will also be fed into the caverns to “make it seem as though the audience is hearing the street sounds above from underwater.” The installation will also feature the work of George Poonkhin Khut further developing his investigations into biofeedback audio installations as he captures people’s brainwaves to create a score for musicians to play. (Read about Khut’s Cardiomorphologies here and here) Phonography, August 24-25, 5-7pm, Paddington Reservoir Gardens, Paddington, Sydney

a room of one’s own

In response to the thriving independent theatre scene in Sydney, The New Theatre has instigated The Spare Room initiative presenting the work of four new-ish local companies. The season kicked off earlier in the year with Dirtyland, a new Australian play by Elise Hearst, and the Australian premiere of UK writer Philip Ridley’s Piranha Heights. The final two shows are coming up starting with Katie Pollock’s A Quiet Night in Rangoon, presented by subtlenuance, telling the story of an Australian journalist in Burma in 2007 during the Saffron Revolution. The final work is Lucky, a physical theatre piece poetically exploring the issue of human trafficking, by Dutch writer Ferenc Alexander Zavaros and presented by IPAN International Performing Arts Network. The New Theatre is currently calling for submissions for its 2012 The Spare Room program with a deadline of September 30. The Spare Room: A Quiet Night in Rangoon, subtlenuance, Aug 18-Sept 10; Lucky, IPAN International Performing Arts Network, Oct 6-22; The New Theatre, Newtown, Sydney; www.newtheatre.org.au

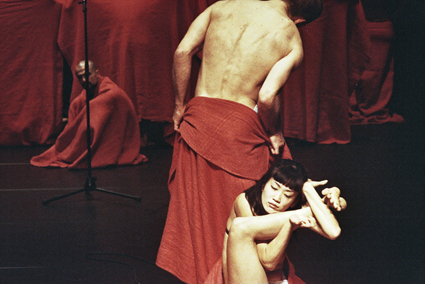

The Hamlet Apocalypse, The Danger Ensemble (Melbourne production)

photo Morgan Roberts

The Hamlet Apocalypse, The Danger Ensemble (Melbourne production)

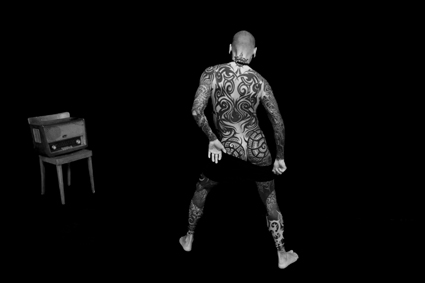

the end of the world as we know it

La Boite has also been showcasing the Brisbane independent theatre scene through its Indie Series. The final installment is by The Danger Ensemble presenting The Hamlet Apocalypse (to be reviewed in RT105): a group of six actors performing Shakespeare’s Hamlet on the eve of the end of the world. The Danger Ensemble is made up of artists from diverse performance backgrounds including Butoh, physical theatre and experimental cabaret. Director Steven Mitchell Wright writes: “We have gone down the path that leaves the work the most open, where time is broken and glimpses of truth and experience can be accessed by the audience in a non-literal and anti-theatrical way (director’s notes).” While Mitchell believes the work “will polarise audiences,” the production was very well received at the Melbourne Fringe Festival in 2010. La Boite Indie, The Hamlet Apocalypse, The Danger Ensemble, Aug 26-Sept 11, La Boite Theatre, Brisbane; www.laboite.com.au; www.dangerensemble.com

Quiet Time workshop with Reckless Sleepers

courtesy the company

Quiet Time workshop with Reckless Sleepers

a bit of shush

CIA Studios in Perth is calling for participants for Quiet Time, a workshop with Mole Wetherell from the UK/Belgium group Reckless Sleepers. Quiet Time will bring together 10 artists from a range of artform areas to explore the “the city as a basis for research and stimulus(media release).” Reckless Sleepers formed in 1988 and often work with a research and residency model to create cross-disciplinary, site-specific works that are “installed rather than presented (company website).” The workshop will take place in December, with applications closing August 29. Participant stipends and interstate travel allowances are available to assist artists to attend the Lab. For more information or to be sent an application form email kate@pvicollective.com; www.ciastudios.com.au/

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. web

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Case Study

photos Justin Harvey

Case Study

WHEN UNDERBELLY FESTIVAL DIRECTOR IMOGEN SEMMLER CASUALLY QUIPPED IN RT103, “PEOPLE LIKE GOING OUT TO COCKATOO ISLAND,” I’M NOT SURE SHE REALISED JUST HOW MUCH: AUDIENCES FOR THE FINAL FESTIVAL DAY—THE CULMINATION OF A 16-DAY DEVELOPMENT LAB—FAR EXCEEDED EXPECTATIONS, REACHING 2,200 PEOPLE.

Extra ferries had to be scheduled as the normal service became taxed, people were turned away at the entrance at times as the festival reached capacity and queues grew to Depression era proportions. Throngs of people across a broad demographic seem to be interested in the alternative arts, as long as they’re in a fascinating location.

Of course the downside was that many of the performance works were designed for a limited audience (some one or four at a time) and even the centerpiece, OJO by Strings Attached with a capacity of 500, was fully booked by the time I arrived at 4pm, so I have to admit, I failed the Underbelly challenge. However I tracked down some esteemed colleagues, Teik-Kim Pok and Sarah Miller, who had much better time management skills, to comment on some of these works. For my part, I spent my time queuing (to no avail) and taking in the installation works that inhabited the nooks and crannies of Cockatoo Island.

Case Study

photo Justin Harvey

Case Study

case study, [xuan] spring, pattern machine

The most impressive installation, and perhaps the most intensive process in Underbelly was Case Study in which six artists—Perran Costi, Jesse Cox, Emily McDaniel, Adam Parsons, Damian Martin and Justin Harvey—moved to the island for the 16-day lab, taking with them only a suitcase. If there were any Survivor-style power plays during the development the final installation was a picture of harmonious communal living. A series of makeshift huts and lean-tos were scattered around an old workshop, each with bedding, curtains, found objects and text curios. Some hummed with quiet sound installations and most glowed hauntingly with projected stills and videos. Plant and moss specimens from around the island adorned surfaces like miniature gardens and small assemblages were to be found in nearly every crevice. Exploring issues of inhabitation, colonisation and migration, Case Study offered a wabi-sabi micro-environment of wonderful intricacy.

![[Xuan] Spring, Ngoc Nguyen](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/48/4854_priest_spring.gif)

[Xuan] Spring, Ngoc Nguyen

courtesy the artist

[Xuan] Spring, Ngoc Nguyen

Ngoc Nguyen also worked with ideas of domesticity in her installation, [Xuan] Spring. During the Lab she photographed the interiors of several of the abandoned houses on the island adorned with objects and elements associated with the Vietnamese Spring Festival. For the final installation the photographs were displayed in a small office/workshop, accompanied by rows of spring plants and flowers. The beautiful simplicity and intimacy of the work was reinforced by the presence of family members serving sweets and tea to visitors. Nguyen’s Spring was impressive for its subtle, yet no less integrated, use of the site

Pattern Machine was an intriguing audiovisual environment and performance by James Nichols, Dan MacKinlay, Jean Poole and Sarah Harvie. A giant inflatable wormlike object occupied one end of a vast workshop while video projections adorned the far end, glancing across a magnificent piece of old machinery. As was the case with most things in Underbelly, I didn’t catch the whole performance (I had to run to catch the ferry home), but the 20 minutes I experienced offered a rich soundscape of field recordings—flocking seagulls, machine rumbles—underpinned by sweet synthesiser tones delivered quadrophonically, with some great use of video masking to create projections that worked specifically with the architectural features.

Gail Priest

Fetish Frequency, Inflection

photos Dylan Tonkin

Fetish Frequency, Inflection

inflection, all you can stand buffet, awful literature is still literature I guess

The island’s colourful past evokes treasure hunt sensibilities and attempting to live up to this promise of adventure, some of the artists responded with works exploring audience interaction. Inflection, an “interactive theatre game,” asks us to imagine an alternate version of Cockatoo Island. Stumbling into the middle of the story, I meet a troupe of ‘facilitators’ in a low-ceilinged room in the Naval Store, black stockings masking their faces. In the centre is a mannequin torso sitting upright amongst black garbage material surrounded by photos of various sites on the island laid out in an ominous looking ring. Above this is a clue played on video loop, prompting us to carry out one of five major rituals. A few audience members hesitantly step forward to fulfill one of these tasks: “build a lover from these objects.” Unfortunately, given the nature of the event, I have to move on and fail to witness the conclusion of this action, but Fetish Frequency’s haunting mix of audience-driven storytelling and installation building/intervening is something I hope to experience in their next outing.

Next door our Underbelly experience was becoming more rumble-belly as we anticipated a feast of sorts in Butterfries’ All You Can Stand Buffet. Billed as ‘’the disfigured love child of Dante’s Inferno and Sizzler,” we are ushered in by a performer who lays out the ground rules (replete with end-of-days metaphors) for moving through the rooms—each a different buffet ‘course’—the changes signaled by the loud clanging of a steel salad bowl.

Beginning our first course we are surrounded by mounds of strewn rubbish and encouraged to sift through black garbage bags for barely edible items, among them heads of iceberg lettuce left in various states of defoliation by previous audiences. Accompanying this is a diatribe on Third World famine and an exhortation to overcome our privileged First World disgust. This prompted some in my audience, already familiar with the practice of dumpster-diving and the earnest activist tenor of the work, to respond in one-upmanship from then on, to which the Butterfries team struggled to respond. Subsequent courses included being force-fed bread rolls, served minestrone soup out of a cling-wrap lined toilet, a makeshift abattoir with a row of raw chickens impaled on a wall overlooking a blood-soaked floor and a dinner party where two performers’ strained exchange invited my restless audience group to weigh in, escalating the action into a food fight. While Butterfries’ audience-wrangling strategies need bolstering, their efforts to visually reference the aesthetic of disgust is a worthwhile achievement for their first collaborative effort.

I choose to decompress from the gastronomic challenge by visiting the Festival Bar for some mulled wine while taking in one of the more relaxed offerings, Applespiel’s Awful Literature is Still Literature I Guess. At this point, surrounded by towers of books, they regale us with a series of abject confessionals which segue into an ironic promotion of books considered obscure and questionable in literary merit completing the bar’s role as a sensory pit-stop for the traumatised, exhilarated and perplexed among us island-hopping conceptual treasure hunters.

Teik-Kim Pok

Whale Chorus, Rhapsody, Paul Blenheim, James Brown, Janie Gibson

photos Josh Morris

Whale Chorus, Rhapsody, Paul Blenheim, James Brown, Janie Gibson

rhapsody, ojo, v

Whale Chorus took the idea of the musical and broke it right across their collective hootenanny kneecaps in Rhapsody. Even at this early stage of development, this short work-in-progress was performed with panache by Matt Prest, Janie Gibson and Paul Blenheim. It was silly, smart, kitsch and funny.

Referencing everything yet nothing I could quite put my finger on, Rhapsody evoked moments of Oklahoma but also Deliverance, Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and Psycho, not to mention various high school musicals, segueing from popular culture to irreligious cult. The costuming for Paul Blenheim and Matt Prest—red checked shirts and tight black pants—was inspired while Janie Gibson’s deadpan Doris Day provided a great counterpoint to boyish petulance, blokey bravado and dang-crazy angst.

Whale Chorus “aims to borrow techniques used for creating music to create theatre” and the effect of translating musical concepts such as polyphony and dissonance into theatrical manoeuvres leads them into some hilariously unlikely places. Matt Prest’s delivery of the Beatles’ “Taxman,” and Janie Gibson’s attempts to get two reluctant lads to sing the Judy Garland standard “Good Morning” reminded me of classic comedy—think Marx Brothers or Laurel and Hardy without the pratfalls. Kazoo, celery, song, story and hypnotism were brought together in an absurd narrative to create something utterly idiosyncratic and funny.

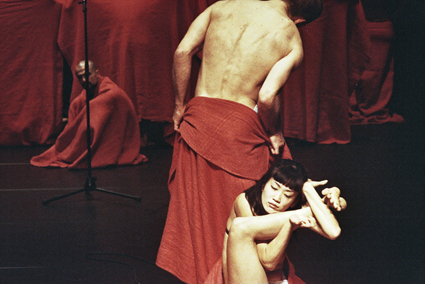

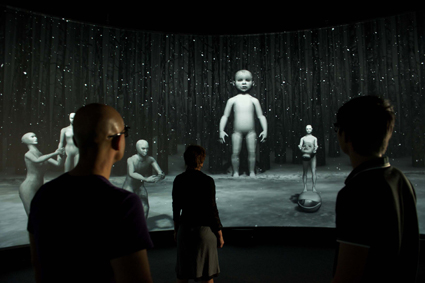

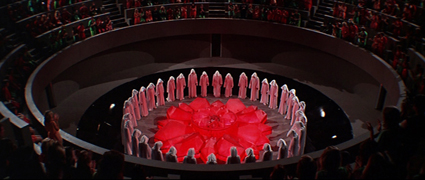

OJO, Strings Attached & Younes Bachir, Underbelly

photo Catherine McElhone

OJO, Strings Attached & Younes Bachir, Underbelly

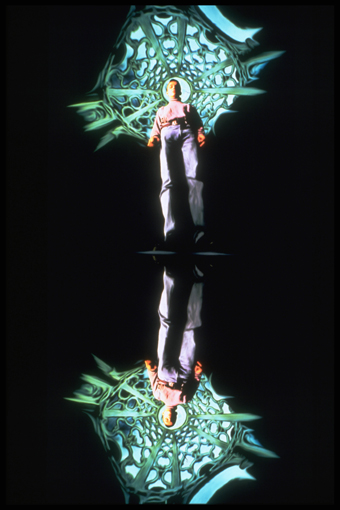

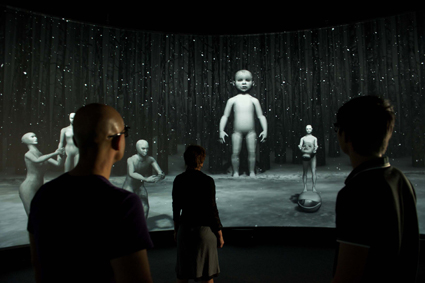

At the other end of the emotional spectrum was OJO created by Strings Attached and Younes Bachir, previously a collaborator with La Fura dels Baus. Brought to Australia by Deborah Leiser-Moore, Artistic Director of Tashmadada (Melbourne), Bachir worked with a large group of highly skilled physical theatre performers as well as emerging practitioners.

Performed at one end of the cavernous Turbine Hall, the work begins before the audience enters the space, with a single performer hoisted high in the air, flailing and spitting words at the gods. On the other side of a large curtain, the audience stumbles across bodies sprawled or curled foetus-like on muddy, wet concrete floors amidst the wreckage and detritus of modern industrial society. The imagery is apocalyptic, the performers intense, edgy and focused. I’m reminded of Nietzche’s dark “primordial unity” that seeks to awaken our Dionysian nature through an evocation of the primal, ritual, extreme physicality and chaos as a means of bringing us to harmony.

Anyone old enough to experience the 1989 production of La Fura dels Baus’ Suz/o/Suz at the Hordern Pavilion will remember the massive spectacle and ritualistic nature of the work: blinding lights, cacophonous noise, water and mud, sex, birth, festival, sacrifice and death, combined with a fantastic physicality and extraordinary aerial work. Audience members ran for their lives as huge machines and implacable performers bore down on them.

OJO worked with similar materials and themes, albeit stripped back, and without elaborate or expensive sets, but the experience was no less intense. One of the most thrilling moments occurred when the performers manually dragged the huge machinery high in the ceiling of the Turbine Hall from one end of the performance area to the other. The horrifying yet compelling momentum of the industrial machine—Blake’s “dark satanic mills”—and its devastating impact on the natural world was powerfully evoked.

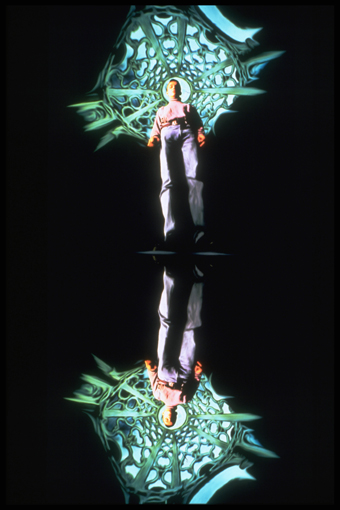

Justin Shoulder, V

video stills Sam James

Justin Shoulder, V

From darkness into light, the strangely weird and fantastical creature that is V emerges from an old, sandstone house in the convict courtyard, one of the oldest sites on the island. White gridlines shimmer and pulsate like visible electricity as this urban demon appears swaying from side to side, carrying a large book with the word V on its cover. An apparition, alien or the ancient ancestor-spirit of Cockatoo island—I have no idea—but that doesn’t stand in the way of my enjoyment of this work. An audiovisual spectacle, this is a huge collaborative effort devised and performed by Justin Shoulder, directed and produced by Jeff Stein in collaboration with composer Nick Wales, a founding member of Coda, video and lighting designer Toby Knyvett working with Sydney Bouhaniche, Cheryle Moore of Frumpus fame and that wizard of theatre spectacle, design and contraption-making, Joey Ruigrok. It was a great end to my Underbelly day.

Sarah Miller

lab work

With the culmination of activities in one big bonanza there is a danger of losing perspective on the developmental status of many of the works in Underbelly, some of which began a mere 16 days before. However audiences could visit the island in the weeks prior to watch the artists right in the midst of the thorny business of artmaking. I regret that I didn’t take up this opportunity, as I may have been able to make a one-on-one appointment with J Dark in Joan of Arc is Alive and Well and Living on Cockatoo Island by Triage Live Art Collective or have the drive-in experience of Julie Vulcan, Ashley Scott and Friends with Deficits’ Spotlight Bunny.

After a smaller-scale festival in the streets of Chippendale last year, the 2011 Underbelly, thanks to its site and more rigorous programming, reached a whole new scale and level of engagement with audiences and artists. If the event continues on Cockatoo Island, it feels as though it would be best to expand to a two-day final event in order to satisfy its eager audience. GP

Underbelly Arts 2011; Case Study, Perran Costi, artists Jesse Cox, Emily McDaniel, Adam Parsons, Damian Martin, Justin Harvey; (Xuan) Spring, artist Ngoc Nguyen; Pattern Machine, artists James Nichols, Dan MacKinlay, Jean Poole, Sarah Harvie; Fetish Frequency, Inflection, artists Jimmy Dalton, Lucy Parakhina, James Peter Brown, Skye Kunstelj, Aimee Horne and Amelia Evans; Butterfries, All You Can Stand Buffet, artists Damien Dunstan, Jennifer Medway, Kirby Medway, Tessa Musskett; Applespiel, Awful Literature is Still Literature I Guess, artists Simon Binns, Nathan Harrison, Nikki Kennedy, Emma McManus, Joseph Parro, Troy Reid, Rachel Roberts, Mark Rogers; Whale Chorus, Rhapsody, artists Matt Prest, Janie Gibson, Paul Blenheim, James Brown; Strings Attached & Younes Bachir, OJO, Younnes Bachir, artists Alejandro Rolandi, LeeAnne Litton, Dean Cross, Kathryn Puie, Angela Goh, Matt Cornell, Mark Hill, Kate Sherman, Carolyn Eccles, Gideon PG, Robbie Ho, Matt Rochford, Elisa Bryant, Charlie Shelly, Julia Landery, Victoria Waghorn, Cameron Lam, Craig Hull, Leanne Kelly; V, artists Justin Shoulder, Jeff Stein, Toby Knyvett, Sydney Bouhaniche, Nick Wales, Cheryle Moore, Joey Ruigrok; Underbelly artistic director Imogen Semmler, executive director Clare Holland; Cockatoo Island, Sydney; Lab July 3-12, Festival July 16; http://underbellyarts.com.au/

This article first appeared in RT e-dition august 23.

RealTime issue #105 Oct-Nov 2011 pg. 5

© Gail Priest & Teik-Kim Pok & Sarah Miller; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Alakazam, 2010 (detail), Adam Adelpour included in HATCHED National Graduate Show 2011, PICA

courtesy of the artist

Alakazam, 2010 (detail), Adam Adelpour included in HATCHED National Graduate Show 2011, PICA

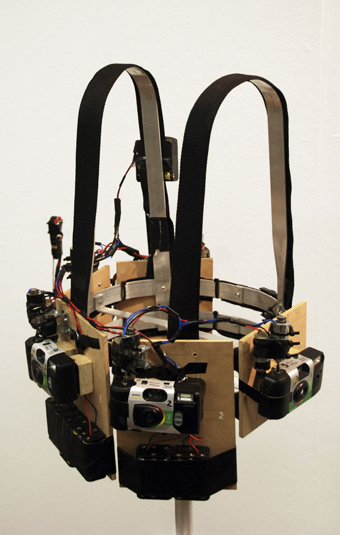

Will artists tread ever so softly and self-censor under the weight of a growing number of protocols, impending new classification legislation and, not least for the training and education of young artists, the nervous reactions of university ethics committees? This is the Burning Issue in RealTime 104, aptly illustrated on this page by Adam Adelpour’s Alakazam. Adelpour is a student from Sydney College of the Arts [SCA], University of Sydney, one of the young artists selected for this year’s Hatched National Graduate Show at PICA. What at first glance looks like a bomb-cradling terrorist rig turns out to be a bizarre 360-degree surveillance device which the artist boldly activated, ie flashed, in the security-sensitive Sydney Opera House precinct. You can read a detailed account of the device and the action on the artist’s blog: adamadelpour.wordpress.com. The other dimension of our annual arts education feature is a survey of Australian content in university curricula and syllabuses. It’s quite revealing, indicating a passionate desire to bring together students and local artists, to attempt to make national connections and to find Australia’s place in a global art context. The ideal consistently appears to be a desire to bring these three dimensions together, avoiding ghettoisation and imbuing students with a sense of history (not least of recent contemporary art practices) and the greater world to which they as artists will contribute.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 2

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Over and Out, 2010, LINK Dance Company, WAAPA

photo Jon Green

Over and Out, 2010, LINK Dance Company, WAAPA

SCAN THE LANDSCAPE OF AUSTRALIAN TERTIARY DANCE COURSES FOR EVIDENCE OF “AUSTRALIAN CONTENT” AND IMMEDIATELY WHAT IS REVEALED IS THAT ITS INCLUSION IS FAR LESS ABOUT PRIORITISING A PARTICULAR AMOUNT IN ORDER TO SATISFY A PERCENTAGE OF NATIONAL INTEREST, BUT IS FAR MORE ABOUT THE PARTICULAR VALUES THAT DIFFERENT COURSES ASCRIBE TO AUSTRALIAN DANCE AS AN ARTFORM.

An important priority within curricula, Australian dance content is defined by various combinations of acknowledgment and celebration of Australian dance works; cultivating an understanding of a lineage of dance artists who have contributed to the development of what we see as current Australian contemporary dance; of utilising and maximising the expertise of current dance artists and transferring those benefits to the students; and possibly of patriotic or nationalistic pride.

working from the local

Dr Sally Gardner, Lecturer in the School of Communication and Creative Arts at Deakin University, says that upon starting their undergraduate degree many dance students “have little knowledge of contemporary dance art either locally or globally, currently or historically.” Given that this is their starting point she asks “why invoke the nation?” suggesting that “perhaps it would be better to think in terms of the local. Making connections with or referring to local dancers has a pragmatic, potentially vocational value.” At Melbourne University’s Victorian College of the Arts (VCA) a strategy to feature the work of Australian dance artists both in performance and in the curriculum has been pursued over the past 10 years. This integrated approach to dance education and training aims for VCA students to become conversant with the work of Australian choreographers and dance companies in a variety of contexts at and beyond the VCA.

A combined pragmatic and referential approach comes from Michael Whaites, Artistic Director of Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts’ (WAAPA) postgraduate pre-professional program LINK. Providing networking and employment opportunities are highlighted goals and the choice of national dance artists and companies is geared towards assisting the graduates from LINK to gain work within the profession: “Australian dance artists are very important…helping the students connect to the landscape and east coast, and helping to familiarise them intimately with some of the current people working in the industry.”

dance artists as teachers

Australian tertiary dance courses value and employ currently practising Australian artists as teachers for their currency of knowledge, their particular artistic practices and the professional networking information and opportunities that can benefit their students. Deakin University’s dance course includes comprehensive representation of local dance artists throughout the many aspects of students’ studies including as teachers, occasional additional visits by guest dancers, unit readings, reference or mention during technique, composition or other workshops and announcements on unit website pages.

The VCA’s current focus on Australian work is described by Associate Professor Jenny Kinder, VCA Dance Undergraduate Coordinator, as “underpinned by the involvement of practising dance artists in curriculum delivery. Participation by practising artists in three of six subjects on offer represents significant exposure to Australian work and practices.”

resource: god bless youtube

At Macquarie University Dr Pauline Manley, Lecturer in Dance Studies, says that Australian dance content is comprehensively included within the Macquarie dance course, “ranging from watching artists on YouTube to setting research tasks to seek out and attend live performances in unfamiliar venues and settings.” The inclusion of Australian content is considered vital in providing students with information about the content and location of what is currently occurring in the Australian dance environment and she praises the ability to access it via the internet: “God bless YouTube and the artists who release their work for the world to see. Thanks to YouTube we can watch Australian contact improvisation, performance artists, improvisations, contemporary dance …”

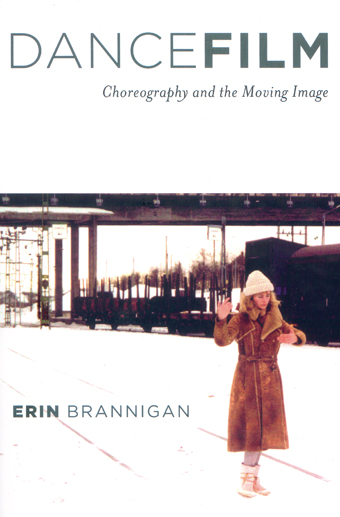

While Pauline Manley applauds YouTube, Dr Erin Brannigan, Lecturer in Dance at the University of NSW places the onus of releasing more Australian dance information into the wider public domain on the works’ creators. Although documentation of dance exists she says “it is very difficult to obtain. Choreographers and dance companies need to take responsibility for this.”

resource: dance as written word

It is generally agreed that currently there isn’t a broad enough body of written text and reference material regarding Australian dance, although resources in areas such as dance film are increasing. Performing arts journals, magazines and publications such as Brolga, the Writings on Dance archive, RealTime and the RealTimeDance portal are quoted as valuable sources of written material, although in total they are few. Key resources that relate to Australian dance are available in other formats—some in the form of living, practising senior artists. Jenny Kinder makes the point that “the issue is not access to information but whether Australian researchers will capitalise on existing primary sources and documents (such as the National Library’s Oral Histories) to produce the kind of dance texts and documentation that have emerged from the United States, Britain, Europe and more recently Asia.”

networks & shared learning

Another challenge is getting students to access information and material about dance artists and practices that occurred before the digitised age, and not to confuse accessibility of information with ease of access to information or the only available information. However, consideration does need to be given to how the current generation of students consumes information, says Associate Professor Cheryl Stock from Queensland University of Technology’s Creative Industries and former dancer, choreographer and artistic director. By students sharing information via blogs, YouTube and social networks, she observes that teaching and learning processes have changed to incorporate more dynamic peer-to-peer exchanges of information: “It’s about the conversations that are being held in whichever format they’re occurring. This has many advantages in engaging students and providing access to work that cannot be seen live but it does not replace the experiential. Learning about dance and learning through dancing provide an essential praxis of theory and practice.”

embodied learning

Critically, dance students need to understand that some information can only be accessed by direct interaction with practising artists. Cheryl Stock says that “to acquire deep knowledge of dance, students need to be in the studio often to directly engage with their learning for a more complete understanding of the ideas they access—and most importantly, that information becomes EMBODIED; it is a type of knowledge that is experienced and transferred personally and these kinaesthetic understandings cannot be acquired through digital platforms. Students need to engage with our contemporary artists and their ideas on a number of levels and where at all possible learn directly from them through classes, secondments and choreographic opportunities.”

learning lineage

Acknowledgement of the history and legacy of Australian dance is the aspect of Australian dance content unanimously considered of utmost importance and relevance for today’s dance students. The knowledge of national and international dance practices and histories is symbiotic and provides a perspective of how Australian dance and seminal Australian dance artists developed, progressed and impacted on current generations of Australian dance artists within local and global contexts. Cheryl Stock says that “there is a tendency for many students to think that various (contemporary dance) practices are new. They need to have access to the lineage of dance artists that have contributed to what exists now. And we also need dance scholars to write those histories.”

In 2012 the VCA will introduce a new subject Dance Lineages which will focus on the development of contemporary dance in Australia in order to contextualise the international contemporary dance trends and influences studied. Jenny Kinder underscores the value that it will be “acknowledged through the prism of Australian dance artists and their various overseas encounters”. Macquarie Dance also shares this view and has a research project underway to establish an audio-visual database of Australian dancing from the 1960s to the present day.

While the principle of prioritising Australia’s dance heritage is a shared theme, the selection of artists focused on reflects each course’s specific aesthetic values, geographical location and the individual experiences of staff. The artists highlighted by different tertiary dance courses and the reasons for their inclusion and prioritisation, are therefore important indicators of the particular character, artistic approaches and aesthetics of the course and what it can offer.

thinking globally, dancing locally

On the issue of inclusion of Australian dance content in tertiary dance courses there is an overarching agreement that it is a fundamental necessity for dance students to experience information and dance work that is excellent and which reaches beyond national definitions, histories and borders; but to be able do this their perspective must be informed by knowledge that is local in order to understand and appreciate the global.

As Cheryl Stock comments: “We live and work in a global world but we need to foreground past and current Australian dance practices and histories for an appreciation and understanding of how what is happening now came to be and why. That is, we need to contextualise the information historically and with an understanding of how the different genres have developed. Australian contemporary dance—and indeed all contemporary dance—didn’t just happen.”

additional resources

The Australian National Library’s Australia Dancing (www.australiadancing.org); Alan Brissenden and Keith Glennon’s Australia Dances, Creating Australian Dance 1945-1965, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2010 (RT 100); and Erin Brannigan’s Platform Paper for Currency House, Moving Across Disciplines: Dance in the 21st Century, 2010. Ausdance National and Routledge’s book on Australian dance with interviews and articles by and with Australian dance artists, academics and critics is due for publication in 2011. The Australian company Contemporary Arts Media’s Artfilms provides DVDs (at individual, educational and other institutional rates) of Bangarra Dance Theatre, Lucy Guerin Co. and Chunky Move (www.artfilms.com.au). Erin Brannigan and RealTime are editing a collection of essays and interviews on specific works by 12 Australian choreographers for publication in 2012 (the choreographers are profiled with articles and video clips in RealTimeDance: www.realtimearts.net/realtimedance). Eds.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 3

© Linda Sastradipradja; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

For Pina, les ballets C de la B

photo Chris Van der Burght

For Pina, les ballets C de la B

FORMER SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE HEAD OF THEATRE AND DANCE, AND SPRING DANCE CURATOR, WENDY MARTIN IS NOW HEAD OF PERFORMANCE AND DANCE AT LONDON’S SOUTHBANK CENTRE WHERE SHE SAYS SHE’S ADJUSTING AFTER SEVERAL MONTHS TO A NEW WAY OF LIFE, INCLUDING ENCOUNTERING MORE DANCE THAN SHE’S EVER SEEN. SHE’S PARTICULARLY PROUD OF THIS HER THIRD SPRING DANCE FOR THE SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE, A PROGRAM OF DISTINCTIVE INTERNATIONAL WORKS AND, FROM AUSTRALIA, ROS WARBY’S MONUMENTAL AND CHUNKY MOVE’S I LIKE THIS.

dv8: can we talk about this?

Martin describes Lloyd Newson’s new work, Can we talk about this?—with its international premiere in Spring Dance—as fusing dance and verbatim theatre to deal with the issues that arise from the 1989 fatwah placed on Salman Rushdie, the threats to the life of a Danish cartoonist for his representation of Muhammad, and the murder of Theo Van Gogh for his criticisms of Islamic culture. It seems that the work will focus particularly on the oppression of women and children in a work rich in interview-based dialogue and inventive choreography. Martin reveals that the cost of presenting Can we talk about this? “was almost beyond us, but the Opera House made the commitment.” She was intrigued that the work was co-produced (with European partners) by The National Theatre of Great Britain “rather than with London’s Sadlers Wells.” This is further evidence that there are works and audiences that crossover and hybridise, as in the programming in Australia of works by Lucy Guerin in Malthouse and Belvoir subscription seasons. Given its subject matter and, apparently, the manner in which it’s played direct to its audience, Can we talk about this? is bound to be as provocative as it is inventive.

les ballets c de la b: out of context, for pina

Coming close on the heels of the sell-out screening of Wim Wenders’ 3D film tribute to the late Pina Bausch at the Sydney Opera House, comes Alain Platel’s tribute. Like DV8’s Lloyd Newson, says Martin, Platel believes that without Bausch his own work would not exist. Platel was taken by the way that Bausch’s creations would “step out of the everyday” and give so much creative responsibility to her dancers (among whom have been a number of Australians). Platel’s tribute pays homage to Bausch’s unique approach but, says Martin, uses the popular music and dance moves of our own time, as well as Bach, to make the connection with his own work for les ballets C de la B. Jana Perkovic wrote, on seeing For Pina at Sadler’s Wells in 2010: “The piece defies description by virtue of sheer over-accumulation: 90 minutes of startlingly original movement with virtually no repetition, on nine different physiques that, even when amassed into synchronicity, preserve individual differences…Not having any narrative frame allows the audience to experience this decontextualised mass of movement on the level of affect, not cognition, free-associating stage images to deep memories. The result is emotionally penetrating and deliriously enjoyable.” (RT98)

pina: a celebration

Further acknowledgment of the Bausch legacy comes on screen over two days in the form of Anne Linsel’s Pina Bausch, a film, and Linsel and Rainer Hoffman’s documentary about the creation of one of the greatest of the choreographer’s works, Kontakthof. (The program will also include Life in Movement, the documentary about the late Tanja Liedtke.) Speakers in the accompanying discussions about Bausch will include Meryl Tankard, Michael Whaites, Kate Champion, Shaun Parker and Lutz Forester who all performed with Bausch’s company.

Israel Galván

photo Felix Vazquez

Israel Galván

israel galván: la edad de oro

When at the Lyon Biennale de Danse in 2007, I saw a gypsy flamenco ensemble perform, unadorned by frills and garish lighting, it was one of those revelatory experiences that put you in touch again with a form that had come to mean little. Martin has seen three works over the years by Israel Galván, a “flamenco revisionist” who brings together traditional form with contemporary dance. In Rome she witnessed him “dance barefoot, kicking up whirls of white dust while accompanied by a pianist.” She was also intrigued by the way “he blurred the masculine and feminine in his form” and accentuated the shape of his dance by largely performing in profile so that every movement detail could be relished. RealTime contributor Erin Brannigan told me she thought Galván’s performance in this year’s Montepellier Danse the best in the program.

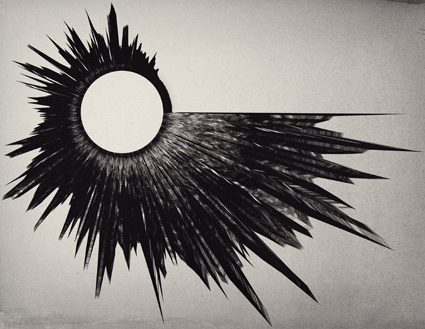

Ros Warby, Monumental

photo Jeff Busby

Ros Warby, Monumental

ros warby: monumental

Although previously enjoyed by Sydney dance audiences courtesy of Performance Space at CarriageWorks in 2009, Martin hopes that Warby’s Spring Dance presentation of Monumental will bring her the much larger audience this truly idiosyncratic Australian dancer deserves. There’s much about Warby to be found in RealTimeDance, including my review of Monumental (RT90). I wrote (and it’s not an easy work to put into words, believe me): “The anti-gravitational appeal of dance is, of course, like our dream of flight and winged selves, but here the embodied connection goes deeper. The audience become birdwatchers who, by way of Warby-Medlin [film]-Mountford [cello] alchemy, suddenly sense not only the dancer’s ‘birdness,’ but also their own, and, as they cast their minds back to Monumental’s opening image, the birdness (and not just of swans) of ballet.” Monumental is visually magical, sometimes funny and has some very interesting things to say about dance…and nature.”

Blazeblue Oneline

photo Byron Perry

Blazeblue Oneline

chunky move: antony hamilton & byron perry’s i like this

Dancers Antony Hamilton and Byron Perry have contributed significantly to the works of Melbourne choreographers, so it’s wonderful to see them step out as a duo with their own creation about the magic of ‘thingness’ as they manipulate themselves and objects about the stage. RealTime reviewer Carl Nilsson-Polias had been impressed with Hamilton’s Blazeblue Online (RT85); he noted “a subtle recurrence of two-dimensional objects, such as cardboard, being given three-dimensional life and movement by the dancers. It is as though the flatness of visual art’s canvas is itself being reconstructed and reconfigured into the dynamic physical nature of dance.” John Bailey wrote of I Like This: “[Perry and Hamilton’s] visual design for the work deserves particular mention, becoming a character almost in itself, with hundreds of perfectly executed changes whose sometimes stroboscopic effect makes lighting operation appear a form of choreography in its own right. It’s self-reflexive dance, certainly, but by incorporating technology in such a sophisticated way it becomes something much more…the result approaches the sublime” (RT89). You can read Sophie Travers’ interview with Antony Hamilton in RT93. For Wendy Martin, I Like This is indicative of the work of a new generation of Australian choreographers, in this case designing, making and controlling an environment before us.

fevered sleep: the forest

UK group Fevered Sleep’s The Forest became part of the Spring Dance program, says Martin, on the recommendation of Brisbane Festival artistic director Noel Jordan. Aimed at young people and families in particular, but not at all exclusively, this maze-like, glass and mirror installation brings together dance, sound and light to create what Martin describes as “interactive dance theatre.”

placing spring dance

The contrast between Melbourne’s Dance Massive and Sydney’s Spring Dance is palpable given the largely national content of the former and the international purview of the latter. Martin is impressed by Dance Massive and sees the two dance events as equally important. Part of her inspiration for Spring Dance came from witnessing large-scale dance events in Germany in 2007-08 “with so much audience and performance engagement, so much conversation—a story going beyond one show—and asking huge audiences to take risks.” A single show at the Opera House might draw 1,500-2,500 ticket sales, she says—unless it’s Akram Kahn pulling 6,000 or so sales. But the 2010 Spring Dance attracted 20,000 people including 13,500 ticket buyers. Martin believes that Spring Dance is a sustainable model for audience development. It’s certainly what Australian dance needs. Of course, should Spring Dance continue now that Wendy Martin has left the Opera House, the event could be what Sydney dance artists also consistently need, greater exposure to local audiences in an international context as enjoyed by the Spring Dance production of Meryl Tankard’s The Oracle in 2009 and Narelle Benjamin’s In Glass in 2010.

–

Spring Dance, curator Wendy Martin, Sydney Opera House, Aug 23-Sept 4

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 4

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dean Walsh, Fathom

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh, Fathom

LAST YEAR, INDEPENDENT CHOREOGRAPHER DEAN WALSH WAS AWARDED AN AUSTRALIA COUNCIL FELLOWSHIP. THE TIMING COULDN’T HAVE BEEN BETTER. THE AWARD PRACTICALLY COINCIDED WITH WALSH’S 20-YEAR ANNIVERSARY AS A PERFORMANCE MAKER. ACHIEVING PROFESSIONAL LONGEVITY IS NO SMALL FEAT FOR AN INDEPENDENT ARTIST. TO BE OFFICIALLY RECOGNISED FOR IT IS ALL THE SWEETER. AND AS THE FELLOWSHIP ALLOWS WALSH TO FURTHER RESEARCH AND DEVELOP HIS CHOREOGRAPHIC PRACTICE, IT ALSO PROVIDES A TIMELY OPPORTUNITY TO TAKE STOCK.

So, how did it all start? Walsh recalls: “I presented my first piece at Performance Space’s Open Season. That was in June 1991. It was a group piece with eleven dancers. I was performing as well.” Walsh is under no illusions about the quality of the work: “Transcendent Nights, it was called. It was very ‘dancey’. I was just out of dance school. Naïve, you know.” The work didn’t go unnoticed however. Walsh laughs: “Sarah Miller [then director of Performance Space] pulled me aside afterwards and said: Come back with a solo next year. I think you’ve got more to say.” And sure enough, Walsh followed her advice. He became, in fact, something of a regular at Performance Space’s short works nights over the next few years – first at Open Season, then, from 1995, at queer cabaret programs such as cLUB bENT and Taboo Parlour. It was here he excelled with highly physical dance performances, exemplifying the spirit of nineties queer politics. The works were often inspired by Walsh’s personal experiences of homophobia and domestic violence—artistic manifestations of standing up for himself.

Around that time, in addition to his pursuits as a solo artist, Walsh also became a sought after performer in works by leading directors and choreographers such as Nikki Heywood, Nigel Kellaway and Garry Stewart. In 2002 he was awarded a Robert Helpmann Scholarship and left Australia to work with Paul Selwyn Norton and Company in Amsterdam and DV8 Physical Theatre in London. Upon his return three years later, Walsh’s choreographic interest had shifted away from the solo format towards choreographing group works. His first ensemble piece, Back From Front, premiered at Performance Space in 2008. Since then Walsh’s work has undergone a continuous evolution both in content and form.

This brings us to Walsh’s Fellowship and the program of activities he has proposed to undertake in the next two years. Walsh: “One of the leading questions for me is: What is the body of the history of my practice and how can I distil it into a system that I feel has integrity in terms of where I want to take my practice now, which is into a whole new content base, I guess, reflecting on the notion of environment, habitat destruction, genetic memory, our social connection and disconnection to the idea of climate change and major social human change.”

The first major thematic shift in Walsh’s work occurred when transitioning from creating solos to making group pieces. Looking at the long-term impact of wartime experience on soldiers and their families, “Back From Front was kind of like the bigger version of everything my solos were,” says Walsh. It was me going away from my own family to listen to other families and other histories but it was still the older way of working. And it was still an earlier concern in terms of domestic violence and where it comes from.”

Dean Walsh, Fathom

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh, Fathom

Now with environmental change and extinction issues increasingly the target of his thematic exploration, Walsh’s focus is currently on research into marine habitats and their bio-diversity. He cites taking up scuba diving in 2008 as the event that kick-started his new found interest. It exposed him, he says, to a previously unknown world and ignited a passion that soon resulted in genuine concern for the future of marine habitats and the survival of marine species, to a point where he seriously considered giving up dance: “I could almost give up art to move into conservation,” he says. And then, after a pause: “But I don’t want to. I’m really interested in how to take my dance practice into this new fascination I have with the need to conserve our marine bio-diversity.”

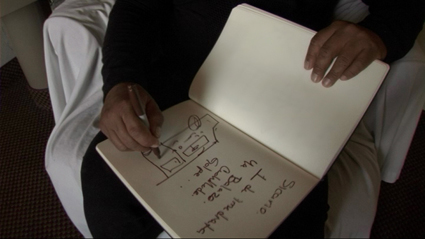

In addition to the exploration of new thematic and conceptual content, a large section of Walsh’s fellowship is dedicated to the choreographic scoring system he has been developing over the last years. It is called Foreign Language, complete with a “grammar” of its own and rules that distinguish it from any other physio-linguistic systems. Walsh explains: “The system is made up of five primary scores that divide into various sub-scores which then further break down into a series of modulations.” Could we have an example? “One of the primary scores is animality,” he says. “The sub-scores are various vertebrate and invertebrate animals. The cephalopods [octopuses, squids], for example, are among them.” What about the modulations? “The modulations relate to the specific physical and textural qualities of a certain species. In the case of the cephalopods, it’s their alacrity. Apart from a soft cartilage skull and a beak, they practically consist entirely of muscle.”

And how is the system used to choreographic purposes, how does it operate in action? “The various scores, sub-scores and modulations can be fused with each other, creating near-infinite possibilities.” Further complexity is added by the fact that some of the animality scores are anatomically impossible to execute for humans. “Some interesting movement gets produced that way,” says Walsh. An example would be one of the cephalopod modules, which is inspired by the Pacific Red Octopus’ ability to fit through spaces a tenth of their size by executing two complex physiological manoeuvres simultaneously—reducing muscular density while extending forward.

Walsh’s Fellowship is primarily dedicated to choreographic and conceptual research, both experiential and practical as well as theoretical. Apart from engaging in studio-based activities, he also regularly attends seminars, lectures and conferences and consults with marine biologists and conservationists. In order to try out some of his ideas in front of an audience, Walsh further conducts work-in-progress showings and recently presented the first instalment, in a series of what he calls ‘touch-down performances’. Entitled Fathom, the event took place in Track 8 at CarriageWorks. Walsh found the experience invaluable: “It gave me the opportunity to interface with an audience and get their feedback. That definitely upped the ante and got me away from the loneliness in the studio. It also helped me to become clearer. I had to put it out there to understand what it is I’m doing. I’m a physical realiser.”

So far Dean Walsh has completed a quarter of the program he is scheduled to undertake as part of his Fellowship. His passion for the project is palpable and his eloquence in describing its various components impressive. And yet, there is a sense that the ambition and sheer scale of his undertaking has just started to dawn on him. Walsh readily admits that at times he finds it rather overwhelming. Tongue in cheek, he states: “I feel like I have a whole ecology of ideas that will last me 10 or more years. I just can’t scope it all yet and I do feel like, I’m not drowning by any means, it’s absolutely not that. In fact, I’m breathing under water but the water is just so immense, I can’t scope it all.”

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 6

© Martin del Amo; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Dean Walsh, Fathom

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh, Fathom

DEAN WALSH HOLDS THE AUSTRALIA COUNCIL DANCE FELLOWSHIP FOR 2011-2012, HIS ARTISTIC TENACITY REWARDED WITH INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT. IN WALSH’S OWN WORDS, FATHOM IS AN EXPERIMENT AND A SMORGASBORD OF IDEAS: A REFLECTIVE MOMENT IN A TWO-YEAR PROCESS.

Walsh is an artist with important things to say. Dance can have a timid political voice but in Fathom Walsh seeks to connect movement theatre with the wider world and a political hot potato: the health of our natural environment. The relationship is not always comfortable or even clear, but the motivations are intense and passionate.

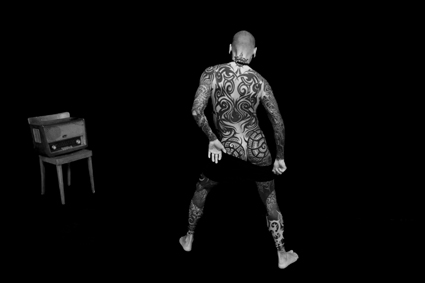

The black box stage is strung with striped tape, cordoned off like a scene of violence. Hanging hooks hold bags of green liquid horror. Implicit in this pre-set image is the thematic destruction that feeds Fathom: “not only was the bush gone, but the entire creek and swimming hole had been filled in. In its place is street after street and house after identical house: suburbia. No gum trees in sight” (program note).

Sitting to one side is a yellow man in a large blue bucket. He has no face. He fishes as a watery soundscore floats. His fishing pole creates a gentle arc against the lines of striped tape. As he stands his upper back leans, curving like the fishing pole. He dips as sound flutters.

This opening scene is intensely aesthetic: shape, colour and line dominate action. While it does become more alive with movement, what remains resilient in Fathom is image. In a series of episodes that fluctuate in tone, intensity and personality, it is be colour, lighting, costume, screen and apparatus that provide the performative punch. In this way Fathom does not cast itself so much as movement theatre or a reflection of the underwater world, but as a series of aesthetic events.

Walsh sits in a spotlight, his hands cast the colour of lobster. He pulls at the featureless face of the masked fisherman, trying to breathe, gulping for air. He twists and pulls and strips away the yellow face. A nightmare vision, this stretchy striptease is impacting, but we are rushing on with no time to linger on matters of strangulating angst.

Liquid lounge music elicits a more fluid dance. Walsh’s body has a signature written in his open joints, raised chest and extreme flexibility. Blown by undercurrents, his soft release is pleasure felt and pleasure communicated, but this oceanic movement moment is fleeting. He continues to strip away the costume. Fingers wave, wiggling his body into violent convulsions as his skin is lit lobster red again. An umbrella turns man into mollusc. He strips again. Silence and breathing become vocal snorts, rasps, sighs and grunts. Now in black he walks tortured down a white runway. He strips again.

Whale sounds herald a comic turn. As he searches for the lost beasts a baffling simian comedy briefly unfolds. He strips again. Now down to his underwear. Text moves down the screen, making this dense journey lecture-like: sometimes spelling out that which is not apparent, but sometimes too complex to grasp, sometimes interfering.

Dean Walsh, Fathom

photo Heidrun Löhr

Dean Walsh, Fathom

Driving trance music catches Walsh in a net before silence once more heralds a return to comedy. With a netted head atop a lurid green dress he dances a camply distorted ballet. I no longer know where I am. The screen image tells me I am at a beach polluted with plastic shopping bags. He caresses himself and strips again.

Colour again. Spinning bags of slimy sputum drip lines of gunk into artistic shapes on the floor. Underneath Walsh sits whimpering amongst the freshly fetid smell. He wails as he flails and slides to escape the glossy mess. He gasps into a surface made beautifully smooth, slides into glides made possible by oily ground. These lines of putrid green become luminescent. The stage is smeared with the muck of humanity and, from this defiled space, the performer leaves, opening a door of light, to enter a cleaner world.

Fathom is baffling. It is crowded with ideas and images: some patently clear, some obtuse. This must be forgiven in an ‘experiment.’ The aesthetics of light, colour and form are the work’s most vital assets. The choreography, only momentarily liquid, seems to reside outside the rhythms of the environment it seeks to embody, with the visual art emphasis yielding flatness rather than depth. But Fathom, in this incarnation, is definitely the promised smorgasbord of ideas.

Fathom, devisor, choreographer, performer Dean Walsh, advisor Paul Selwyn Norton, lighting Clytie Smith, costumes Rebecca Bethan Jones, sound editor Kingsley Reeve, video Martin Fox; Performance Space, Carriageworks, Sydney, May 19-22

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 7

© Pauline Manley; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

University of Queensland (Australian Drama) students perform Harvest by Manjula Padmanabhan

courtesy University of Queensland

University of Queensland (Australian Drama) students perform Harvest by Manjula Padmanabhan

AUSTRALIAN CONTENT IN THE CURRICULA AND SYLLABUSES OF COURSES IN AUSTRALIAN THEATRE HAS BEEN CONSIDERABLY ADVANTAGED BY THE AVAILABILITY OF PLAY SCRIPTS (THROUGH CURRENCY PRESS, ESPECIALLY, AND PLAYLAB) AND DISADVANTAGED BY THE ABSENCE OF A NATIONAL THEATRE MAGAZINE—LONG SOMETHING OF A MYSTERY. CONTEMPORARY PERFORMANCE AND CUTTING EDGE THEATRE HAVE BENEFITED FROM THE PRESENCE OF REALTIME SINCE 1994 (BUT FOR THE MOMENT ONLY ARCHIVED ONLINE 2001-PRESENT). THERE ARE KEY ONLINE SOURCES LIKE AUSSTAGE, SEVERAL SIGNIFICANT BLOGS (BY ALISON CROGGAN AND JAMES WAITES) AND JOURNALS AND, BEYOND THAT, EVERYWHERE I ASKED, A CONSIDERABLE HUNGER AMONG LECTURERS, RESEARCHERS AND STUDENTS FOR A MORE PALPABLE SENSE OF THE PERFORMING ARTS ACROSS THE NATION—IN WORD AND ON SCREEN.

Opportunities to see theatre and contemporary performance, both current and past, on DVD and online look set to improve, and that includes digital broadcasts to regional cinemas, as the Sydney Theatre Company did recently with Andrew Upton’s adaptation of Bulgakov’s The White Guard. Of course, the Australia Council and various State Government touring schemes have already improved access—a glance at Melbourne’s Arts House current program on our back page is a sure indication of improvement, with its inclusion of a number of Sydney-based artists. The rise of small, innovative live art festivals and the likes of Brisbane Festival’s Under the Radar program have yielded cross-border opportunities only dreamt of a decade ago. Accessibility on a variety of platforms is on the increase—so important for regional universities, but often no less so for students in our huge, sprawling cities with the added impediment of escalating ticket prices.

At the same time, it’s the face-to-face, body-to-body engagement between students and practising Australian artist lecturers and guest directors and teachers that is a top priority, of course more so in training than history or theory courses, but even there you will see increasing emphasis not only on seeing the work but also engaging with it, for example as observers, documenters, reporters and trainee dramaturgs (as in Performance Studies at the University of Sydney; see RT105). In both kinds of courses you’ll find opportunities offered for playwriting and group devising, so that students gain some sense of being ‘inside the artist’ as their own capacities and skills evolve.

For our 2011 survey, I’ve approached teachers (where available—it was that time of the year) from a range of schools and departments asking them where Australian work fits in their courses. Inevitably it’s regarded as important in itself but, more critically, in an international context—a mix of treasuring and exploiting the local scene, attempting to gauge a national perspective and finding our place in the global picture—mighty tasks but ones often tackled with verve and invention.

university of wollongong

Staff members (including practitioners Tim Maddock, Chris Ryan and Janys Hayes) in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong told me that students enrolled in both the Bachelor of Performance or in the Bachelor of Creative Arts (Theatre) “work with contemporary Australian performance practitioners to devise performance works, write and perform their own texts, as well as presenting productions by both Australian and international playwrights. There is a strong emphasis on contemporary Australian artists in both the practical and history/theory program. Students are encouraged to see festivals and site-specific performance, by both independent and major theatre companies, as well as live art, contemporary performance and post-dramatic theatre.” However, it is felt that “the lack of available performance and theatre documentation is an issue.” Keeping up with even recent work can be a challenge making it potentially “redundant, unless properly recorded and readily available.

“Our reading lists include a number of titles from the Rodopi Series on Australian theatre and performance, as well as Currency publications on Australian artists and practices. However, publications on playwrights dominate the field and significantly more DVD documentation is required. At present many recordings are limited to either personal collections or theatre company archives, and can be difficult or impossible to access. This impacts on the ability of staff to teach across a broader range of contemporary performance work. We address this issue predominately by engaging guest practitioners who teach strategies of contemporary performance by example. This intersects with the theory program, which studies the history of these artists and provides the opportunity for such artists to screen and discuss examples of their work.” Guest artists who have directed and/or devised work with students since 2007 include Geordie Brookman, Kate Gaul, Carlos Gomes, Regina Heilmann, Deborah Pollard and from Korea, Park Younghee.

university of ballarat

Ross Hall, Lecturer In Acting in the regional University of Ballarat says that its Arts Academy runs two practice-based Degree Programs one focusing on acting, the other on musical theatre. “Most of the art that’s created here is done so under the broad umbrella of pedagogy and intensive performance training. Over the past 10 or so years, we’ve performed Australian content on a fairly regular basis—mainly text-based works, covering many genres from full-length plays to new Australian musicals. We run scene classes on specifically Australian content—again, mainly contemporary plays. We also run devising strands in the early parts of our courses; [these] map developments in Australian drama and musicals [and can explore] pre-existing Australian stories in a dramatic way. Our students devise work that travels out into the community. We’ve taken part in the evolution of new work, co-producing these with freelance writers and artists. We’ve co-produced issue-based community theatre. We’ve commissioned new Australian works, both dramatic plays and musicals. We have visiting artists and current practitioners give lectures and workshops. We engage practicing directors to work on many of our performance projects.”

flinders university

Jonathan Bollen, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Drama, School of Humanities, Flinders University (and a regular contributor to RealTime), focuses on the fact that “students go on to become the colleagues and spectators of the artists they learn about at university, so it is crucial they learn about who is making work now.” He teaches a course titled Live Arts and Performance that introduces third year students to performance art, post-dramatic theatre and contemporary performance. “It focuses on selected artists and companies within an international field, and traces connections with recent developments and current practice in Australia. It is designed to equip students with the knowledge to navigate international arts festivals and the field of contemporary performance in Australia. The OzAsia Festival in Adelaide provides a focus for the study of intercultural performance in Australia.”

This placement of local performance in an international context is reflected in course structure: first year students focus on three contemporary Australian works in substantial detail; second years “studying the history of modern theatre learn about the New Wave, Australian Performing Group, Nimrod and the Black Theatre movement. At fourth year, I teach topics on Contemporary Australian Drama that explore the production history and dramaturgy of recent works from Australian playwrights, including Wesley Enoch, Jane Harrison, Andrew Bovell, Katherine Thomson, Hannie Rayson, Daniel Keene, Patricia Cornelius, Tom Holloway and Noelle Janaczewska. Australian plays from the 70s to the present are regularly produced as part of the department’s activities.”

Bollen would like to see “more books that focus on the work of particular Australian companies and artists—books that combine documentation of product and process, with analysis and critical reflections. It would be great to have books on Australian Dance Theatre, Bangarra, Back to Back, The Border Project, Chunky Move, Urban Theatre Projects, Version 1.0 and more. Performing the Unnameable (Currency Press with RealTime, 1999, editors Karen Pearlman and Richard Allen) was great when it was published. We need another collection on contemporary performance for the last decade.”

As for magazines and online publications, “RealTime is a crucial resource. I couldn’t teach Live Arts and Performance without it. It is required reading for students. It is the only resource that provides national coverage and international context for contemporary performance in Australia. The other online resources that are crucial for teaching are AusStage and AustLit. I also rely on the websites of companies and artists. The scholarly journals About Performance, Performance Paradigm and Australasian Drama Studies are valuable for in-depth studies, but their coverage is not so extensive.” A vital component of the department’s approach is that “four of the six permanent lecturers in Drama at Flinders are practising artists. Their work as artists forms a core part of their teaching. It is also visible to students in work on productions on campus.” In his reply to my queries, Bollen appended an extensive and impressive list of the websites for artists, companies, festivals and venues in Australia and around the world that are part of the syllabus for his Live Arts and Performance course.

university of queensland

Playwright Stephen Carleton is responsible for Australian Drama at the University of Queensland: “We offer an Australian Drama course that spans the entire 20th and early 21st century from Federation to the present.” The final weeks of the course focus on contemporary practice through a thematic approach, for example “Engagement with the Asia-Pacific Rim” is projected for 2012. “Additionally, we feature the work of Urban Theatre Projects in Sydney and Tracks Dance Theatre in Darwin within the ‘post-national theatre’ rubric of our Contemporary Theatre course…We also offer a third year course in Dramaturgy and Play Writing in which students learn contemporary dramaturgical practices and theory and apply this to each others’ new writing projects.”

“As a practicing playwright and convenor of the Drama Major,” writes Carleton, “I have a substantial investment in the centrality of an Australian focus in our program, and all staff at UQ Drama are committed to encouraging students to place the Australian cultural and industrial theatre experience in an historical and international theatre context. As well, UQ Drama produces Australian works one semester in every four. Most recently that has been work by Van Badham. We encourage students to experiment with the short plays they write in Dramaturgy and Playwriting in terms of form and content.These are frequently produced by the University’s theatre group Underground as part of their annual Bugfest Program.”

As for books, “we set Maryrose Casey’s Creating Frames, about Indigenous theatre practice, alongside broader Australian survey texts such as those by John McCallum and Geoffrey Milne as required reading.” A particular challenge, says Carleton, is the absence of “texts placing contemporary Australian theatre practice within an international context.” However, Carleton claims that “UQ Drama’s emphasis on Theatre Through Time and Space represents the most comprehensive canonical approach to Western European and International theatre (including Chinese, Indian and Pacific theatre traditions) from Antiquity to the Present of any tertiary theatre program in Australia. Placing contemporary Australian theatre practice within this broad spatial and temporal history is a central tenet of our approach.”

However, he adds, “It is incredibly difficult to get information about what’s happening in the regions and the capital cities beyond Sydney and Melbourne. A dedicated national theatre magazine would be a wonderful thing—a specialised theatre magazine that augments RealTime’s focus on multi-form and genred performance, dance, film review and analysis—that would be an excellent resource to have.” He is appreciative of AusStage and AustLit for providing increasing online documentation.

The observations made in Part 1 of this survey add up to a strongly felt need to be able to understand and teach Australian performance on its own terms but within the framework of the national and international perspectives that this country has struggled so long to attain. The work is there, books, journals, archives, new media tools, touring networks, but something’s missing or, better, something’s growing—but how well formed will it be for the performers and performance scholars of today and tomorrow?

Part 2 of this survey will appear in RealTime 105, October-November, and will include observations from Peter Eckersall, Associate Professor of Theatre Studies in the School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne; Laura Ginters, Lecturer in the Department of Performance Studies at the University of Sydney; Clare Grant Lecturer in the School English, Performing Arts and Media the University of New South Wales; and Helena Grehan, Senior Lecturer in the English and Creative Arts program at Murdoch University, Western Australia.

RealTime issue #104 Aug-Sept 2011 pg. 8

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

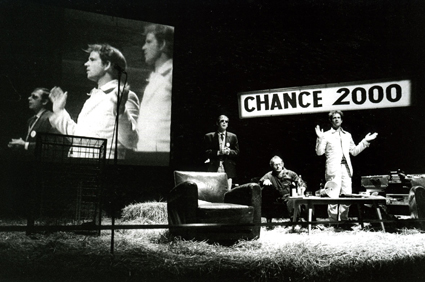

{$slideshow} THE LAST CO-PRODUCTION BETWEEN QUEENSLAND THEATRE COMPANY AND BELL SHAKESPEARE I’D SEEN WAS HEINER MULLER’S ANATOMY TITUS FALL OF ROME: A SHAKESPEARE COMMENTARY WHICH WAS AN IMMENSELY POWERFUL, MEMORABLE AND RELEVANT PIECE OF CONTEMPORARY THEATRE, A BLOODY AND INESCAPABLE DISSECTION BY MICHAEL GOW AND JOHN BELL THROUGH THE LENS OF SHAKESPEARE AND MULLER OF THE COLLUSIVE NATURE OF CONTEMPORARY POWER AND VIOLENCE.

Their latest collaboration, Faustus, albeit providing solid, rambunctious entertainment that scarcely flagged, appeared at the outset to lack the same intensity of focus. There was ample scope, I thought, for this production to put itself more on the line. Instead what at first seemed to be a confusion of eclectic irony and disparate references was ultimately made clear in this new recounting of the legendary Faust, the scholar who sells his soul in exchange for knowledge of the universe and worldly powers.

The western world, especially as it presents the face of modernity, has long been characterised as Faustian, and non-westerners, from the most powerful to the poorest, appear to be ready to make any bargain with the devil to gain access to what is perceived as a cornucopia. This perception is taking us all to hell, or at least to a fiery end to the planet. And, leading us there, climate change sceptic Rupert Murdoch who in recent media appearances eerily resembles John Bell’s seedy portrayal of Mephistophilis as an Ocker small time, seen-it-all gangster. Bell’s was a peculiarly soulless portrayal, I thought, until the penny dropped…Mephistophilis has no soul.

Jonathon Oxlade’s set was living hell. That is to say, it grandly facilitated what in essence was a very racy production. The conceit was that its denizens were performing a show within a show, all for the mystification and damnation of Faustus. It harked back to travelling players, puppet shows, Piscator and the Weimar Republic, and used a plethora of means from documentary film footage (although this might have been updated to the 21st century) to tacky life-size mannequins as multiple framing devices. Musical references ranged from Mahler and Liszt to kraut rock. Part necessity, part Gow’s aesthetic choice, the acting style was hard, straightforward, unsentimental. Nevertheless, individuals shone through: Jason Klarwein as a Brian Ferry Lucifer, or hunched over disguised in a Richard Nixon mask; Vanessa Downing remorseless as Hecate; Catherine Terracini exhibiting the raunchy aplomb of a 1950s movie star as Beelzebub.

In his writer’s notes, Gow indicates that he has based his adaptation primarily on Christopher Marlowe’s Dr Faustus (at least, the lines regarded purely as Marlowe’s) and JW Goethe’s treatment of the same theme in his Urfaust that preceded Faust; the Tragedy Parts I and II. Gow points out that Marlowe’s collaborators padded out the drama with farcical knockabout, and Goethe introduced the story of the young girl Gretchen. The Marlowe version presented a series of ‘shows’ or plays within plays, so Gow decided to include the episode of Gretchen as another of these ‘shows.’

Even so, as movingly played by Ben Winspear and Kathryn Marquet, it is the most human episode in what otherwise might have seemed a relentlessly cynical piece, and speaks directly to Gow’s vision of love, love carnal and love exalted in the words of Marlowe’s own, The Passionate Shepherd to his Mistress. Throughout I warmed to Gow’s love of the English language of the period which performed a particularly nostalgic threnody at this juncture for our own lost innocence and experience, of the half-familiar, half remembered words from school poetry text books, addressed to the schoolgirl Gretchen. The revelation of the heat of Gretchen’s adolescent desire was searing and poignant and personal in this production. The outcome of this disproportionate love affair has Gretchen mistakenly poisoning her mother with a drug given to her by Faustus so they can meet at night. Faustus, much to the disgust of Mephistophilis, has genuinely fallen in love with Gretchen, but cannot save her from execution, nor does she want him to, putting her faith instead in the merciful nature of divine, not human, justice.

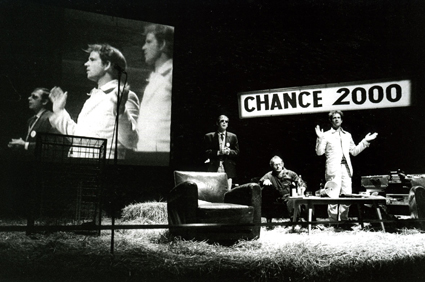

Writing in the 18th century when the conflict of science and faith was less literally incendiary than in the 16th, Goethe was free as a natural scientist as well as a poet to express his fellow-feeling for Faust’s ambition to unlock the secrets of the universe, and so in the end assigns him a less dastardly fate than the one designated him by Marlowe. For Goethe, the love of a good woman was Faust’s salvation. Faust: the Tragedy Part II, declares that, “The Eternal Feminine leads us on.” Marlowe’s Faustus tries to strike a bargain with God by promising to burn his books, only to be condemned for his double apostasy by God’s silence, and Faustus is dragged screaming to Hell. Gow for the 21st century interrupts the narrative precisely at the point where God is silent, the actors explaining that this has all been theatre, that Heaven and Hell are merely stage props, and condemning Faustus to the freedom of his own conscience as he makes a swift exit through an audience that now stands similarly condemned.