Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Crowd Theory – Port of Melbourne, 2008, Simon Terrill, produced in association with Footscray Arts Centre and Port of Melbourne, photo Matt Murphy

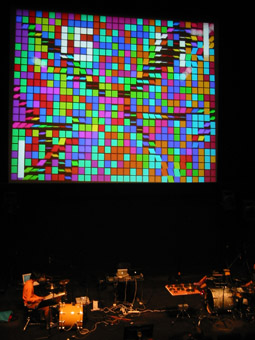

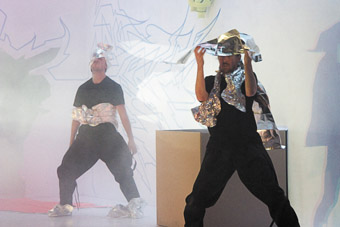

INSIDE THE SECURITY-CONTROLLED PORT OF MELBOURNE, AUGUST 2, JUST ON 5.30 PM: A BROODING SKY, AN EERIE SOUNDSCAPE, SHIPPING CONTAINERS, SCATTERED WEEDS AND PUDDLES, AND 160 WARMLY DRESSED ‘PARTICIPANTS’ COMBINE IN AN HOUR-LONG ‘MOMENT’—THE CREATION OF THE FIFTH IN SIMON TERRILL’S CROWD THEORY SERIES OF PHOTOGRAPHS. THE RESULTING IMAGE CONVEYS A SENSE OF THE TENUOUS RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN A MAJOR URBAN LANDMARK AND THE COMMUNITIES THAT SURROUND IT, AND THE IRONIC NARRATIVE OF A FROZEN ‘CROWD’, WHOSE PRESENCE IN THE PHOTOGRAPH TESTIFIES TO ITS COLLECTIVE AFFINITY WITH THE PORT.

Crowd Theory—Port of Melbourne is, for Simon Terrill, a kind of proposition: both an exploration of the physical space of the Port and a kind of documentary fiction based around the responses of participants to the location. While the scene is carefully constructed—the patch of earth sandwiched between West Swanston Dock and the Coode Island liquid storage facility appears much like a film set—Terrill is not interested in directing participants. Instead, he asks people to consider their relationship to the Port as they form the ‘crowd’ that he captures from atop a 6.5-metre scaffolding tower.

Between the endless beeps and clunks of the dock area and the dark silence of the Coode Island terminal, this crowd is restless, curious. The sun is about to set as people tuck into hot soup, compare gumboots, beanies and scarves, and watch the awesome display of cranes unloading a nearby ship. Four busloads of local residents, interested ‘outsiders’, port workers ranging from office staff to truckies and engineers, a few kids, amateur artists and sundry others have been shuttled across from Footscray Community Arts Centre—producer of the Crowd Theory series and partner with the Port of Melbourne Corporation for this image. As the clouds move in and the light softens, marshalls lead the crowd into the shot and the event begins to take shape.

Simon Terrill has worked with Footscray Community Arts Centre to create Crowd Theory images in four other locations: by the Maribyrnong River at Footscray (2004), at Skinner Reserve in Braybrook (2004), at Footscray Station (2006) and at Southbank (2007). The Footscray photograph won him the $10,000 KPMG Tutorship Award in 2005. Looming clouds have been a feature of all but one of the photos, throwing an enclosing moodiness over scenes of saturated colour and precise composition. The Southbank image stands distinctly separate, its participants both dwarfed by, and part of, a wall of high-rise windows and balconies.

The Port of Melbourne shoot unfolds rhythmically under bright lights: 10 shots are taken throughout the sunset hour, and during each 10 or 15-second exposure the slowly evolving soundscape gives way to a long, solid tone. As the shoot progresses, obvious fascination with the usually hidden landscape gives way to individual preoccupation with the next shot: what we will do, what we will think. Before each exposure, Terrill reminds us over the PA to spend the duration of the exposure focusing on “that one Port thought”—and everyone seems to take it seriously, embracing each extended ‘moment’ with a deliberate, small gesture in the midst of the scattered whole.

Terrill insists on the importance of allowing each person to respond and represent themselves as they choose. “I see the hour of the making of the picture very much as a ritualised hour”, he says, adding that his role at that point is simply to facilitate that ritual. For Terrill the final photograph will encapsulate “all that precision beforehand, and then, in a sense, the anti-precision of the crowd space.”

The process feels strangely unreal, like a cross between friendly gathering, facilitated trespass and private journey. The location itself seems part real, part artifice—another contradiction that Terrill is keen to explore: “that tension between the fictional image, the things that have gone into making that image, and the attributes which come from that place.”

Crowds, says Terrill, are formed both of shared experience and a kind of “unconscious group mind”, and this idea has been central to all five Crowd Theory images to date. The photograph selected for the final 1.8 x 2.4-metre print is the one he sees as capturing the ‘moment’ during the ritual in which a coherence begins to show itself in the pattern of bodies. Having employed the same process for each image in the series, Terrill says he’s learned to recognise that moment, usually somewhere towards the middle or end of the shoot, when participants’ uncertainty and exploration gives way to a kind of group energy.

Citing Elias Canetti, Terrill describes this ‘crowd-moment’ as being “one of the true moments of equality, where differences between people do drop away.” Canetti’s Crowds and Power, he says, begins with the statement that human beings’ primary fear is that of being touched. “The crowd situation removes that fear”, says Terrill, “and all these interesting things start to happen, psychologically. It’s quite beautiful, the idea of genuine equality, for that fleeting moment.”

Further threads feed into the overall project, with Footscray Community Arts Centre, the Port of Melbourne Corporation and the artist, not to mention the participants, all having an investment in the aesthetic outcome. For Footscray Community Arts Centre the project marries critical artistic practice with community engagement and for the Port Corporation it serves an important community relations function. The final shot seems to be horizontally layered: the ‘community’ almost floats in the middle ground, suspended between the chosen location and the massive port infrastructure behind.

There is also a paradoxical stillness—the hour-long ‘ritual’ was an hour of almost-constant movement as participants explored the site, talked to strangers, watched the cranes and the sunset. The image of the frozen ‘moment’ is indeed a fiction—the long camera exposure can’t be discerned directly in the photo, except for some blurring in the Panamax cranes on the wharf. Terrill’s humble crowd finds its feet and stakes its tenuous claim, both co-existing with and deferring to the mystique of the machinery and the process that goes on, 24/7, behind the wire fences.

–

Crowd Theory—Port of Melbourne, artist Simon Terrill, produced by Footscray Community Arts Centre in partnership with the Port of Melbourne Corporation, Aug 2, Port of Melbourne; Exhibition, Mission to Seafarers, Melbourne, Aug 28-Sept 28,

Urszula Dawkins is a freelance writer, editor and arts worker based in Melbourne.

See cover for the complete Crowd Theory–Port of Melbourne photograph.

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 49

© Urszula Dawkins; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

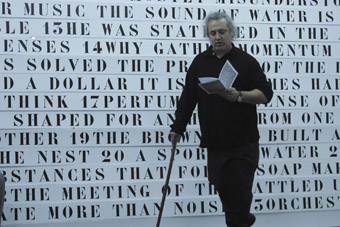

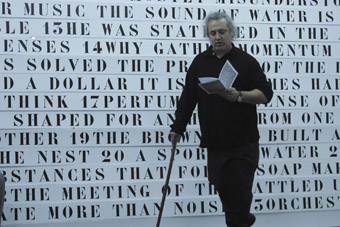

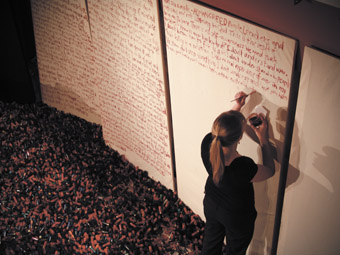

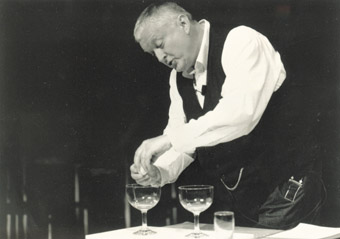

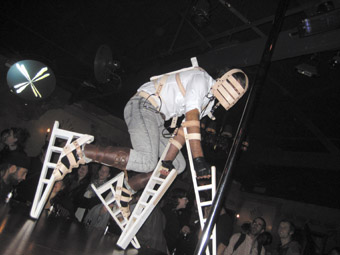

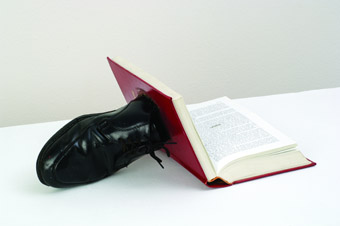

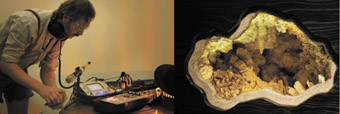

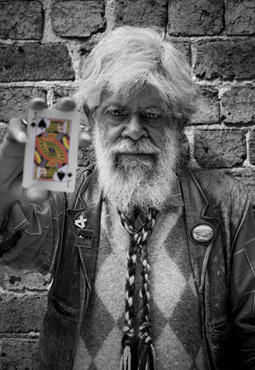

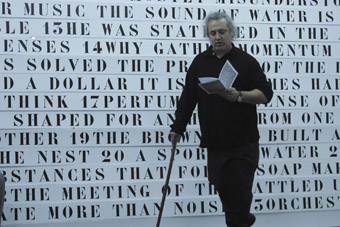

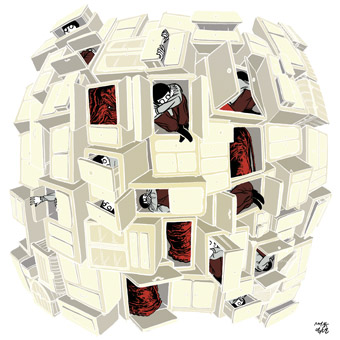

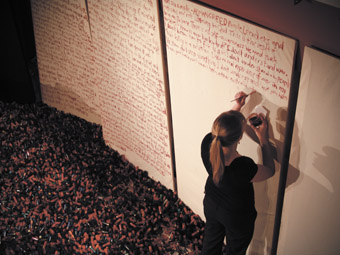

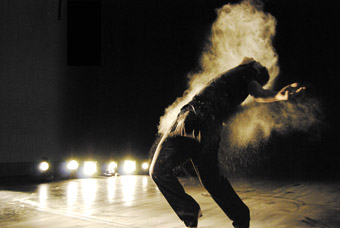

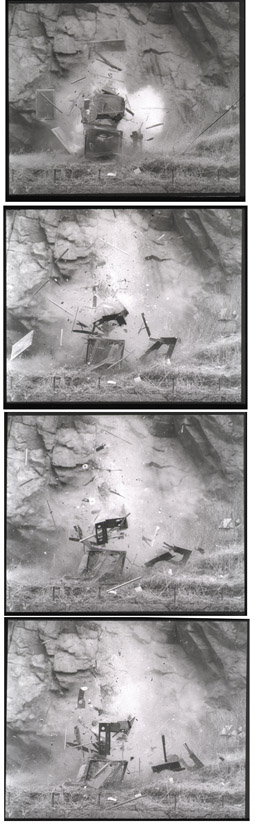

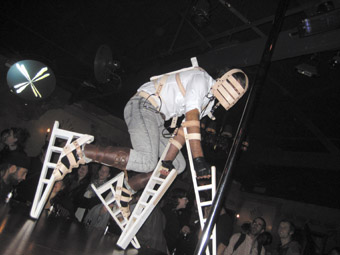

Ruark Lewis, A Babel Reading-Machine (2005)

photo William Yang

Ruark Lewis, A Babel Reading-Machine (2005)

RUARK LEWIS IS A PASSIONATELY POLITICAL AND COLLABORATIVE ARTIST WORKING ACROSS AND INTEGRATING PAINTING, DRAWING, INSTALLATION, ARTIST BOOKS, PUBLIC ART, PERFORMANCES, AUDIO AND VIDEO WORKS. HIS METHOD, WHICH HE TITLES “TRANSCRIPTION (DRAWING)”, OFTEN TAKES THE WORK OF OTHER ARTISTS—COMPOSERS, POETS, CHOREOGRAPHERS, ANTHROPOLOGISTS AND FELLOW VISUAL ARTISTS—AND TRANSFORMS IT INTO ABSTRACTED TEXT EMBODIED IN IMMACULATE SCULPTURAL INSTALLATIONS IN A RANGE OF MATERIALS INCLUDING CLOTH, TIMBER AND STONE, OR TRANSPOSED ONTO THE FACES OF BUILDINGS, AS IN RECENT PUBLIC ART WORKS. THIS ARTICLE REPRESENTS A SMALL PART OF A FASCINATING CONVERSATION YOU CAN FIND AT WWW.REALTIMEARTS.NET.

Like a good poem, a Ruark Lewis work encourages contemplation and promises delayed revelation; then it’s art that stays with you. The man himself is more immediately accessible, an ubiquitous and energetic arts presence (despite a taxing physical disability) and an eager conversationalist—one for whom conversation, he says, is the source of much of his art, building on the images that first occur to him and take flight through talk and are then realised often in collaboration.

A long conversation with Ruark Lewis is a rich journey into cultural history from the 1980s on, of which his own career is a fascinating part. After studying ceramics, Lewis turned to curating public events for four years for the Art Gallery of New South Wales in the late 1980s. The resulting programs brought together a wide range of artists in performative mode. Doubtless, these telling juxtapositions and potentials for partnerships inspired the conversations which became his own collaborative art in the 1990s and up to the present. He created RAFT, a major work with Paul Carter for the Art Gallery of New South Wales and other commissioned works—for the 2000 Sydney Olympics, 2006 Biennale of Sydney and Performance Space. He collaborated with Jonathan Jones on an installation called An Index of Kindness at Post-Museum in Singapore 2007. His recent outdoor installations and sound works in the City of Sydney focus on the consequences of urban development. In October this year he travels to Canada where he’ll create a commissioned public art installation called Euphemisms for the Intimate Enemy for Toronto’s Nuit Blanche festival.

the public house

I asked Lewis about his City of Sydney project, which has recently taken him to Millers Point with its small remaining population of an older community residing amidst new developments and the palpable wealth of new apartment dwellers in the Rocks and Walsh Bay. He describes it as “a public artwork, which includes agit-prop elements, working with a group of people, studying the area and trying to develop a spoken word archive piece, an archive of community comment about lifestyle in the area at this time to do with ‘the public house.’ I’m looking at the ways that development encroaches upon traditional communities living in the inner city areas.” Lewis sees Sydney as having been through several visionary planning periods and with “a remarkable political history when you look at what the BLF forged with the Green Bans…It’s a history of significant counterpoints between the dissident voice, the resistant voice and the government and the developers.” The words of the community, material for Lewis’ text, are being found at the Darling Harbour branch of the ALP and the National Trust and Tenant’s Union.

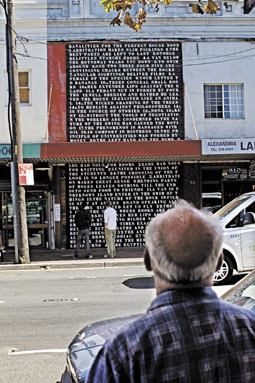

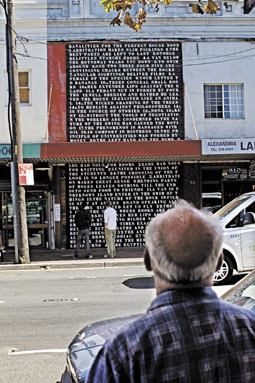

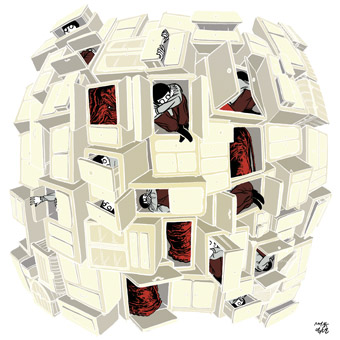

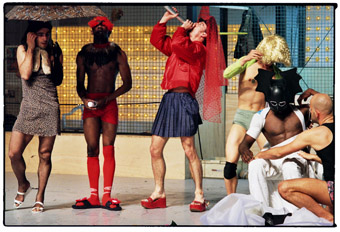

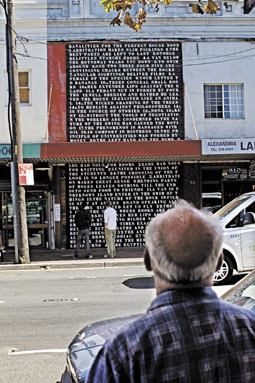

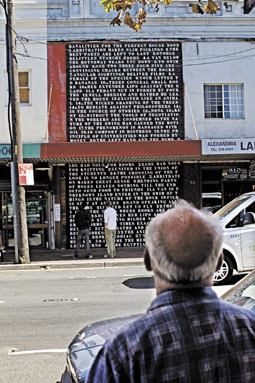

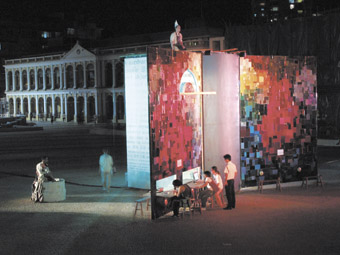

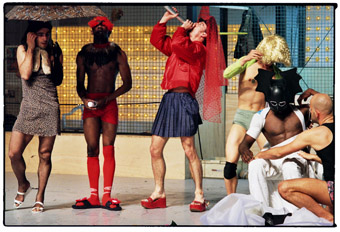

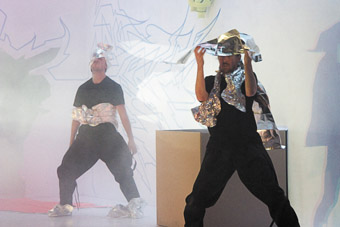

Banalaties for the Perfect House installation, Slot Gallery

photo Alex Wisser

Banalaties for the Perfect House installation, Slot Gallery

Lewis is keen “to make an environmentally integrated artwork. That’s how we worked at Homebush on public art at the Olympic site, making Relay with Paul Carter’s text during 1999-2000 as a Sydney Olympic Games commission. There are no spaces between words and I designed a colour code to cross-reference through the ongoing sequences of five rising stone steps. We had three kilometres of texting going up and down those stone bleachers. The planners were very keen to create a public art that would environmentally integrate with both the site and the sporting events and audience. They didn’t want decorative art baubles. I thought that was a workable approach for an ongoing strategy for placing works in the public zone…I’m still working on that idea and trying to find ways of lightly integrating installed works into the actual building fabric. I’ve done it on couple of locations recently. At an artist-run-initiative called SLOT in Regent Street Redfern I made a seven-metre high façade on the front of the building using the width of the shopfront downstairs and closing off the apartment windows upstairs and taking the text all the way to the parapet. It’s a peoples’ poem called Banalities for the Perfect House.”

We watched and spoke to a lot of people in the street in Redfern to see what their reactions were. A grandmother was drunk in the street and she had tears in her eyes as she stared across the road. “What’s this? What’s this?”, she kept crying. I asked her what the matter was and she replied, “I’ve got to explain this to my grandchildren because when I come up here shopping with them they’re gonna ask about it.” So I said “maybe it’s poetry.” She said, “I know it’s fucking poetry! But what does it mean?” I said, “I’m not quite sure what it means.” She said, “Ah! come on it’s not that complicated.”

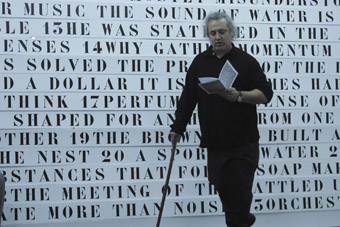

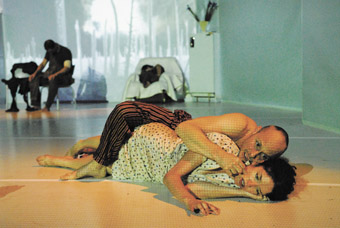

An index of Kindness, Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, 2008

courtesy the artist

An index of Kindness, Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, 2008

municipal signs & other objects

Lewis’ most recent show, at Chalk Horse in Sydney’s Surry Hills, draws on work from his shared show with Jonathan Jones at Singapore’s Post-Museum. The gallery was hung with flags stencilled with words from Nathalie Sarraute’s play SILENCE. Below, on the floor and plinths, everyday found objects had been painted with red, black and white stripes and markings, making the gallery-goer doubly attentive—to where they trod and how they were regarding the art. Lewis surmises that he’s using the gallery to test out some of his outdoor optical and spatial systems: “I’ve been considering the sculptural objects in the show as decoys. They’re like the rocks of Mer in the Torres Strait. Eddie Mabo identified a bunch of rocks around his Island of Mer as being the markers for the language or community zones. I thought that’s a very useful message for all Australians to start to recognise…”

In Singapore, says Lewis, “I was actually looking for garbage. I thought, here’s a place where you can’t have long hair, you can’t chew gum, what can you do? So I started making work about the garbage—on the streets, in the countryside or washed up on the beach…I stencilled messages onto pieces of garbage.” Then he placed the garbage back where he found it and made a photographic record: “This formed an intimate poetic puzzle. I wanted to leave messages for people anonymously. I avoided the fear of arrest by photographing the evidence before and after I removed it. Sometimes I kept elements of the garbage to paint an abstract pattern on it—with red and white or black and white stripes painted in gouache.”

the artist begins

We step back in time to Lewis’ beginnings as an artist. He went to Sydney Boys High School where “One day I went up to the art room and a friend of mine was throwing on the pottery wheel. I became totally mesmerised how that form came up out of his hands and fingers. I loved the slithering plastic action of the clay that formed in his hands. I went straight out and bought a bag of clay that afternoon and made a sculpture, not a pot as such.” With a photographer brother and musician and painter cousins, Lewis describes himself as “sort of coming from a Jewish artistic family—a tribe of mercantiles and artists. According to the painter Cedric Emmanuel our earliest Australian relative was Michael Michaels. He was a forger who was pardoned in 1809 and left Sydney returning to London and he started an orchestra. We’ve always had painters and musicians in the family so making things seems natural to us.”

Lewis studied Ceramics at the Sydney College of the Arts: “It was difficult for me physically but I needed the tangibility of clay.” But a major influence there opposed his interest in ceramics: “the composer David Ahern in the Sound department. David was a total radical. He’d been working with Cornelius Cardew in London and for two years was a personal assistant to Karlheinz Stockhausen. He came back to Sydney in the early 70s and among other things he ran a Sunday new music workshop out of Inhibodress Gallery. That was the group called Teletopia and AZ Music. Tim Johnson and Mike Parr and Peter Kennedy ran the avant-garde concept gallery the rest of the week. But on Sunday the experimental artists ran an open studio where trained and untrained musicians joined together to perform music. Although I wasn’t involved in those early years I’ve been very interested and was highly motivated and inspired by Ahern’s practice. It was wild. It was recklessly terrific. I thought this is really what art’s about. Because it was a language made of sound and music…Ahern was very discouraging of my interest in ceramics and always urged me to paint and draw.”

But, says Lewis, “Ceramics gave me a sort of classical education, which I may not otherwise have received in such a serious avant-garde art school.” An interest in architecture has also been “infinitely useful.” Such contrasting influences were to yield a seriously idiosyncratic artist. The sense of difference was compounded in 1984: “I was expelled from Sydney College of the Arts. That was pretty demeaning—it really wasn’t my fault. I also had been expelled from Sydney Boys High School in 1978. Perhaps both these rejections shore me up as a kind of outsider in art—in that I seemed able to miss out on certain unnecessary things exactly at the right time.”

the artist as curator

Lewis began first as a reader and then as a curator of poetry readings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales and then with Emmanuel Gasparinatos “who programmed a new media event in the theatrette called Sound Alibis with 14 artists including Rik Rue, Warren Burt, Sarah Hopkins and Vineta Lagzdina. There were Super 8 films and sound works and live performances. I developed the program further the next year with the poet and scholar Martin Harrison [who] was interested in the writer/performer as live presence…This began a really successful curatorial collaboration [becoming Writers in Recital]: it made the AGNSW the stage to a wide range of writers and musicians, composers, filmmakers, visual artists, performers dancers, radiophonic composers…I kept working out ideas of how to get the most radical types of experimental art out to the widest audience possible…even radio stations like 2GB would give me a five minute interview each season. I saw it as an act of anti-elitism to promote radical art to a willing public.” The big names, poets like Judith Wright, David Malouf or Les Murray, were programmed to attract large audiences who would witness, for example, “the soprano Elizabeth McGregor singing the Margaret Sutherland settings of early Judith Wright poems alongside the relatively unknown work of Allan Vizents, William Yang, Ania Walwicz or Jonathan Mills.”

escape to melbourne

After four years of curating, “in August 1990 I escaped Sydney. In Canberra I found a copy of TGH Strehlow’s Journey to Horseshoe Bend. It’s a biography/autobiography about the death of his father, the missioner Carl Strehlow in Central Australia in 1922. I started reading what turned out to be a transformative book for me.” It was important in developing Lewis’ art of “transcription” and “texting”, which would later lead to a major work with Paul Carter.

About the origins of his artistic process, Lewis explains, “I wanted to lay in poetic lines from poets I was reading at the time, like Rilke’s Duino Elegies. I wanted to actually enact it as a trace. At the time I was working on musical and sound transcriptions in the form of drawings. That’s how I’d begun texting into works and making abstract cross-overs from one art form to another.” He made diagrammatic drawings of sound works—acoustic music and then the work of the Sydney composer Robert Douglas who was making large-scale works on the Fairlight CMI.

my university

In Melbourne, Lewis spent time with Paul Carter, the director Peter King, Jonathan Mills, Warren Burt, Chris Mann, Vineta Lagzdina and Rainer Linz. The experimental music scene was particularly influential, coming out of the Clifton Hills Community Music Centre and the NMA magazine: “The Rainer Linz and John Jenkins’ 22 Australian Contemporary Composers anthology was the sort of curatorial guide I’d been looking for at AGNSW. There had been little like that sort of thing operating in Sydney…That was also the era of the ABC’s radio’s The Listening Room. Carter had been editing the Age Monthly Review which we’d all contributed to over the years. This was an artistic atmosphere I called ‘my university’.”

In Melbourne Grazia Gunn, director of ACCA offered Lewis a major solo exhibition opportunity which he worked on for two years. “I finished the Robert Douglas transcriptions, which ended up being 48 metres of extended drawing. The 48 panels occupied the Lotte Smorgon Room at the old ACCA in Melbourne’s Domain. There were studies of Douglas’ Homage to Bessemer. I made a room of literary transcriptions based on the French newspaper Le Monde. I’d been in Paris in 1991 and I found a way to look at the demarcations between the generating forces in commercial print media. It was a simple critique of how photography, journalism and advertising worked in concert on the pages and how that formed the capital which is the motivation for a daily publication.” The exhibition was part of Melbourne Festival in 1992: “Melbourne was into high postmodern and neo-expressionist painting then, and along comes an incredibly cool minimalist show with regional underscores. It was shown there for a lengthy 14 weeks.”

But the Melbourne show did not result in Lewis being immediately picked up elsewhere. He comments wryly, “I like the fact that you can work ‘fairly privately’ in Australia. I always understood that experimental art would be ignored by the local art cognoscenti and that the avant-garde was taken up by the academies that could easily canonise it in what I regard as a pseudo international context.”

the experimental realm

Lewis makes strong distinctions between the realms of the avant-garde and the experimental: “It was the expansiveness, I suppose, of the experimental realm, the idea that art and production could take on other forms in constant flux and I could rewrite them…” And there was a correspondence to this work outside of Australia for my artistic friends. John Cage had picked up on Chris Mann’s work and set it for an opera. What I find most interesting in writers like Mann and Walwicz is the certainty of their regional voice. [W]ith the experimental, there’s a sort of fraternity that I like, keen about reading through each other’s work, reading the sound waves that each artist arrives with.”

Lewis enjoyed this feeling when he met Kaye Mortley and René Farabet in Sydney: “Martin Harrison was a friend of Kaye’s. All sorts of interesting people came together at the Harrisons’ house. The dinners often went until dawn. When René and Kaye came to Australia a sort of sound circle developed around them and the Listening Room at the ABC and at UTS. René Farabet was director of the radiophonic atelier program called France Culture, so there were significant cross-overs with people working here. I went off to Paris in 1991 and had the best time of my life.” Lewis worked with Mortley on a rendering of the play Pour en Oui Pour en Non (Just for Nothing) by Nathalie Sarraute: “I immediately had a vision for setting the players’ script marked out on the page in different colours. The colour would navigate the reader through the text like a graphic score.”

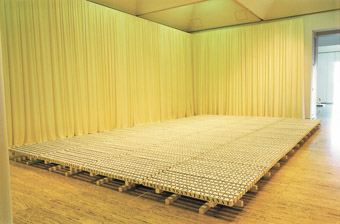

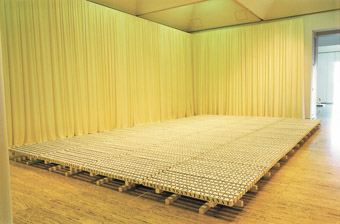

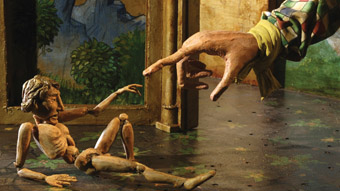

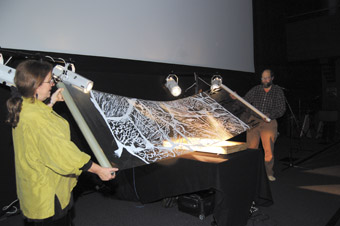

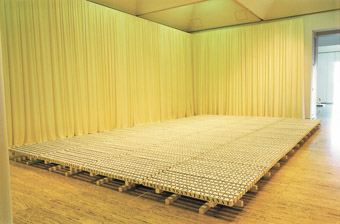

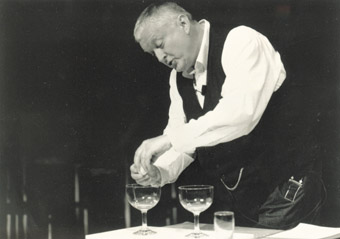

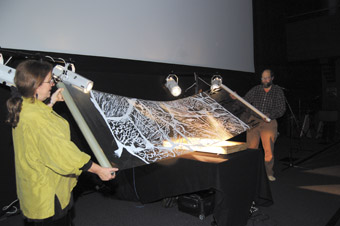

RAFT (2005), with Paul Carter, collection Art Gallery NSW

photo Ian Hobbs

RAFT (2005), with Paul Carter, collection Art Gallery NSW

the raft journey

Asked about the genesis of RAFT, Lewis explains, “I often have visions of things—I see them in visual daydreams and then follow the image directly along into the work. I saw a large gridded structure that seemed to extend out along the surface, so I set off in that direction. The timber of RAFT weighs 1.5 tons. I started testing possible materials when I was staying in Melbourne in 1993. I later made three large Water Drawings which joined RAFT at the Art Gallery SA showing in 1997. Then our book, Dept of Translation, appeared in 2000 to coincide with the exhibit at the Sprengel Museum, Germany which occurred in 2001. So, only about seven years gestation. The Art Gallery of NSW where it was first exhibited acquired the work earlier this year.”

“We were looking at the Arrernte water myth of Kaporilja as the main poetic cross-reference for RAFT. RAFT symbolises the carriage that Carl Strehlow was transported down from Hermannsburg to Oodnadatta to get a train to Adelaide because of his fatal illness. But he died on the way, just north of Fink at Horseshoe Bend. RAFT has to do with issues of translation in the desert. It allegorically acts as a portrait of the classical intercultural brokering of the language scholar and evangelist missioner Carl Strehlow with his links to the first phase of modern anthropology. What’s so amazing is Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara performed various Arrernte and Lorritja songs at the Café Voltaire in May 1917…Three songs were performed, maybe with movement, and probably in the presence of James Joyce and maybe Lenin both of whom were resident in the neighbourhood. So, there’s the modernist trace again.”

the artist performs

I ask Lewis about the performative aspect of his work. In the exhibition at Chalk Horse there’s a beautiful recording of Amanda Stewart and Lewis doing something quite dramatic and very funny and largely unintelligible (but oddly familiar as social exchange) with occasional literal utterances. Lewis explains, “I have became increasingly interested in the process of concretising language and making a score I can follow and make performances from. Last year I asked Amanda” [whom he declares an inspiration] “to work on an improvisation that would in a non-representational way convey three emotions: anger, joy and sadness. As we huddled around a microphone in the studio we both began giggling, wondering how ridiculous we were, but a really intimate moment between artists emerged as we worked out a range of responses that we might record. Rik Rue collaged our efforts adding layers and depth and spatial elements which formed a kind of audio space poem at Post-Museum in Singapore in 2007. I called it An Index of Emotions. I think visitors were surprised and confronted by those spatial effects and some of the sobbing sounds and angry tones were quite distressing.”

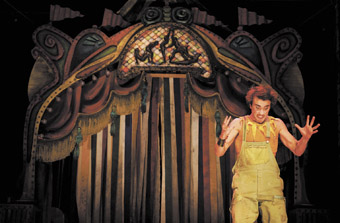

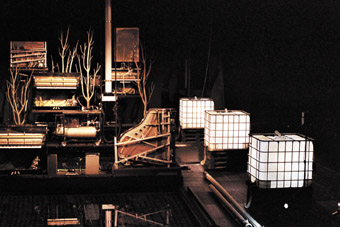

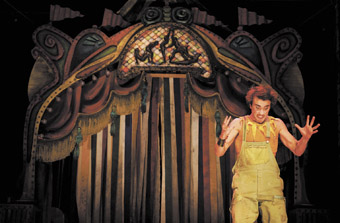

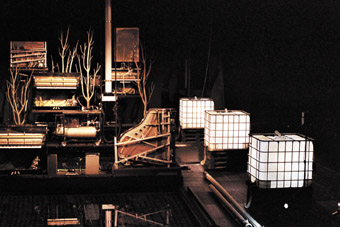

Euphemisms for The Intimate Enemy

nuit blanche, toronto

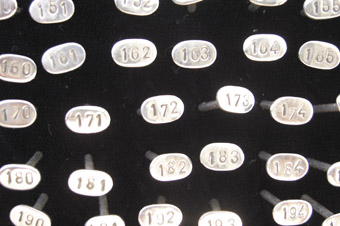

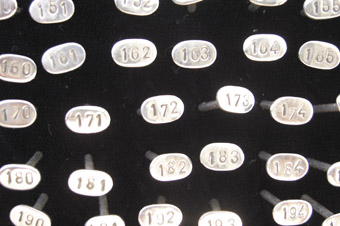

Lewis’ work for Toronto’s Nuite Blanche (an all night, one night exhibition of 155 works across the city) is a sound installation called Euphemisms for The Intimate Enemy, with a duration of 12 hours . As with The Banalities of the Perfect House “the sound is computer generated but will be a live collage when the computer is started around 7pm on the night of the event. I’ve devised an installation of 550 oil drums to be stacked as a curtain wall between two 19th century industrial buildings. Each word of the Euphemisms is stencilled onto coloured (black and yellow) painted drums and will form an illuminated text in the void.”

See also full interview transcript.

www.ruarklewis.com

RealTime issue #87 Oct-Nov 2008 pg. 50-51

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Euphemisms for The Intimate Enemy

RUARK LEWIS IS A PASSIONATELY POLITICAL AND COLLABORATIVE ARTIST WORKING ACROSS AND INTEGRATING PAINTING, DRAWING, INSTALLATION, ARTIST BOOKS, PUBLIC ART, PERFORMANCES, AUDIO AND VIDEO WORKS. HIS METHOD, WHICH HE TITLES “TRANSCRIPTION (DRAWING)”, OFTEN TAKES THE WORK OF OTHER ARTISTS—COMPOSERS, POETS, CHOREOGRAPHERS, ANTHROPOLOGISTS AND FELLOW VISUAL ARTISTS—AND TRANSFORMS IT INTO ABSTRACTED TEXT EMBODIED IN IMMACULATE SCULPTURAL INSTALLATIONS IN A RANGE OF MATERIALS INCLUDING CLOTH, TIMBER AND STONE, OR TRANSPOSED ONTO THE FACES OF BUILDINGS, AS IN RECENT PUBLIC ART WORKS.

Like a good poem, a Ruark Lewis work encourages contemplation and promises delayed revelation; then it’s art that stays with you. The man himself is more immediately accessible, an ubiquitous and energetic arts presence (despite a taxing physical disability) and an eager conversationalist—in fact conversation, he says, is the source of much of his art, building on the images that first occur to him and take flight through talk and are then realised often in collaboration.

A long conversation with Ruark Lewis is a rich journey into cultural history, of which his own career is a fascinating part. After studying ceramics (of which he’s still fond and a new work, a book about pots, is on the way), Lewis turned to curating public events each year for the Art Gallery of New South Wales in the 1980s. The resulting programs brought together a wide range of artists in performative mode. Doubtless, these telling juxtapositions and potentials for partnerships inspired the conversations which became his own collaborative art in the 1990s and up to the present.

Lewis has collaborated with writer Paul Carter, Nathalie Sarraute, Angelika Fremd & Ingaborg Bachamann, Rainer Linz, Jutta Hell & Dieter Baumann and Jonathan Jones. He has created work in Berlin and Singapore; Raft, a major work created with Carter, toured to the UK and Germany; and his commissions include works for the 2000 Sydney Olympics, 2006 Biennale of Sydney, Performance Space and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. He collaborated with Jonathan Jones on an installation called An Index of Kindness at Post-Museum in Singapore 2007. His recent outdoor installations and sound works in the City of Sydney focus, his website says, “on the theme of home, the homeless, huts and the public house.” In October he travels to Canada where he’ll create a public art installation called Euphemisms for the Intimate Enemy for Toronto’s Nuit Blanche festival.

sharing the public house

Before turning to Lewis’ career I asked him about his City of Sydney project, which has recently taken him to Millers Point, with its small remaining population of an older community residing amidst new developments and the palpable wealth of new apartment dwellers in the Rocks and Walsh Bay and the new suburb of Barangaroo.

RL I’m making a public artwork, which includes agit-prop elements, working with a group of people, studying the area and trying to develop a spoken word archive piece, an archive of community comment about lifestyle in the area at this time to do with “the public house.” It’s not precisely about public housing but the public house, a shelter for the street person, the homeless person and about the kinds of housing in general in the area. I’m looking at the ways that development encroaches upon traditional communities living in the inner city areas. (Mayor of Sydney) Clover Moore talks about “urban villages”, but I’d like to talk about a kind of city tribalism and urban history.

The City of Sydney has had three visionary planning periods forwarded by Francis Greenway, Sir John Sulman and George Clarke There have been architects like Peter Myers and Lesley Wilkinson who have built significant public housing projects in the city’s inner suburbs. Col James is a legend for his work and ideas around Redfern. Bill Lucas was my first mentor in urban planning and architecture. In the 1960s he was very focussed 0n saving Paddington from slum clearance and demolition. There’s been consistent conflict between the notion of slum clearance, new developments in public housing and developers in the City of Sydney since the early 20th century. It’s an expensive city. There’s a remarkable political history here when you look at what the BLF [Builders & Labourers Federation] forged with the Green Bans. That’s had an international influence responsible even in formative years of the Green Party in Germany. It’s a history of significant counterpoints between the dissident voice, the resistant voice and the government and the developers. So I think the issues to do with the status of the underdog are really important to focus on for urban activists. The massive corporate/state mentality is keen to erase our community history of resistance. It’s a situation where we hasten to forget. Right now we’re all very conscious of the nature of over-inflated value of property.

KG Do you negotiate your project with the Council and building owners?

RL Yes. I want to make an environmentally integrated artwork. That’s how we worked at Homebush on public art at the Olympic site [making Relay with Paul Carter during 1999-2000 as a Sydney Olympic Games commission]. The planners were very keen to create a public art that would environmentally integrate with both the site and the sporting events and audience. They didn’t want decorative art baubles. They wanted art as user-friendly contextual forms not visually rhetorical objects. I thought that was a workable approach for an ongoing strategy for placing works in the public zone. Especially if you wanted to utilise space to make a public poem. I’m still working on that idea and trying to find ways of lightly integrating installed works into the actual building fabric. I’ve done it on a couple of locations recently. At an artist-run-initiative called SLOT in Regent Street Redfern I made a seven-metre high facade on the front of the building using the width of the shopfront downstairs and closing off the apartment windows upstairs and taking the text all the way to the parapet. It’s a peoples’ poem called Banalities for the Perfect House. Here’s a selection from it:

1. Arbitration makes slim pickings 14a. The wicked smashing of the trees 15c. Without the tools of negotiation the workers are condemned 16. The nature of the swing has caused the motion 17. A phenomena is massaged by oil 19. The principle of universities is formed with money 20. The left hand and the dumb 21. He has nous for rooms 22. She had nous for knitting 23. United in the union of the students 24. A crossing of the floor is no longer possible

The materials had previously been part of a theatre work at Performance Space in Cleveland Street in Redfern but generally the people of Redfern wouldn’t have readily accessed it. Moving the text outside the theatre seemed a stimulating extension and use of the original efforts.

[Melbourne composer] Rainer Linz and I were really keen on looking at the ideals of the visions for housing in Sydney and the potential for social inequity that gentrification enforces. In response to this we developed an installation-cum-music theatre work. Parts of that later were adapted to the street which was very startling, like a fish out of water. We had part of the set in the street for five weeks. They were large but delicately hand-stencilled white characters on black timber boards extending across the front of the building. It looked boarded up. The surface could have been hit by graffiti artists or damaged by vandals or scribbled on during that period. It was interesting to see it was actually still in pristine condition when we took it down. We documented a lot of people stopping and reading the work in the street during the day and the night.

KG Did it have a sonic element?

RL No. It was just textual. It could have had that. It was fairly cost effective to put up. We installed it in three hours, literally transforming a whole facade and street. That was a real surprise to the cosmopolitan Redfern community—all of a sudden the walls were talking and it wasn’t advertising, it wasn’t municipal signage. We didn’t even seek official permission.

KG Was there any explanatory material with it?

RL Gina Fairly and Tony Twigg arranged an information sheet on the front of the building, but I must say I would have liked to have presented it anonymously like a surrealist’s dreamscape.

working the public

KG You’re politically and socially motivated but your work resides in a modernist tradition that wants to make its audience work and not be given any easy solutions or instant intelligibility. Is that an issue for you?

RL Yes, especially when it’s in a really public art zone like at the Sydney Olympics site. Paul Carter’s Relay text is quite difficult, like Russian constructivist Zuam poetry. There are no spaces between words and I designed a colour code to cross-reference through the ongoing sequences of five rising stone steps. We had three kilometres of texting going up and down those stone bleachers. I find audiences always engage in difficult work—to me engagement is all one really needs. My modernist bent comes from my long interest in architecture, through the systems that Bill Lucas taught me and also the Le Corbusier principle of The Modular (the font I use generically was first adapted by Corbusier). I’ve been able to manage things and control designs, writing, audio, video, paintings, theatre, installation or pages of books—anything and all measure of things in the way that architects project manage their sites. It’s the very structure of a given thing that in turn supports another structure that leads out beyond itself.

KG It must be great to be able to say you’ve created three kilometres of texting.

Banalaties for the Perfect House installation, Slot Gallery

photo Alex Wisser

Banalaties for the Perfect House installation, Slot Gallery

RL I was told by a visiting Turkish journalist that no-one in the world could easily boast about that sort of structure. The conceptual artists I greatly admire appear generally to be putting out one-liners—effective as that may be! But I think of text as part of literature. We find that people read parts of the whole so we write and code the work with that fragmentation in mind. The work is readable and puzzling at the same time. I’ve always understood that’s what poetry does: meaning being temporarily suspended. You don’t just have a poetic spectacle that spells the whole message to be consumed immediately. I’m against automatic consumption. We watched and spoke to a lot of people in the street in Redfern to see what their reactions were. And sometimes the initial reaction was anger, “Why the fuck is that here?” I was talking to a taxi driver (I didn’t tell him that I had anything to do with those Banalities). He said he was pissed off at first seeing it there. I said, “Do you go past there very much?” He said, “Yeah, at least two or three times a day to the airport.” But in the end he liked it. He said. “I started to read the lines and I went, ‘Fuck, what’s that doing there? It’s poetry.” A grandmother was drunk in the street and she had tears in her eyes as she stared across the road. “What’s this? What’s this?”, she kept crying. I asked her what the matter was and she replied, “I’ve got to explain this to my grandchildren because when I come up here shopping with them they’re gonna ask about it.” So I said “maybe it’s poetry.” She said, “I know it’s fucking poetry! But what does it mean?” I said, “I’m not quite sure what it means.” She said, “Ah! come on it’s not that complicated.”

KG The crafting of the work, its look, I think is also something people appreciate enormously.

RL And not just the “look”, but the materials. Once you get up close to the surface you can see its materials are basic. Everything we work with are the sort of materials anyone could work with in the back shed or garage. It’s just packing crate timber and colour paints. That honesty of materials is something I’ve wanted to employ for a long time. I think it breaks down the barriers of fine art authority to a simpler commonality. I see that as one of the significant aspects of Brutalist architecture—its modest materiality.

KG You’ve done another version of this in another location?

Ruark Lewis, An Index for the Homeless

RL Recently we placed a work called An Index for the Homeless on a building at 27 Abercrombie Street, between The Resistance Centre and MOP Gallery. MOP have been interested and very supportive of what I’m doing. Both at their artist-run-initiative and also at Hazelhurst Regional Gallery for the Cronulla Riot exhibition that Ron and George Adams curated. I made two installations down at Sutherland which where called Euphemisms for a Riotous Suburb. In June they agreed to housing my street installation in the wall cavity outside the gallery.

There are some arched alcoves in the facade, making them modules across the the entire surface of the building that is three metres square. I’ve designed into it a hut structure that fits within a form of a house made out of stencilled zeros. It’s a simple square structure that has a triangle and rectangle within it. The triangle is at the top, forming an apex as the roof and a rectangle underneath making the walls of the house. So it’s a square, a triangle and a rectangle. There’s the modernist activity in operation again. Form informing form. I thought of it as a concrete poem as well. We stencilled 10cm high characters so they can communicate from a long distance away. This was not an artwork that you go up in front of to experience the brushwork. You have to be at least 20 metres away to get the peripatetic effect. It’s part of a man-made environment, heavy with four lanes of traffic where the optical concerns are experienced spatially.

We installed a sign above the main door of the gallery. It looks like an institutional name for the entire building. It says, “An Index for the Homeless.” It’s as though we’d instantly created a research centre for homeless people. It’s become a bit of a joke actually. I didn’t expect it to work like that—a game of nomenclature, a poetic association generated by chance. Alongside that I painted a board with a quote from Ania Walwicz’s short story called House, which reads, “SALZ FOR SALT SALZ FOR SALT SALZ I AM IN MY HOUSE NOW I STAND.” It’s a fairly mysterious line on a curious site. You can hear people uttering Ania’s words. And they don’t just say it once. they seem to perform it several times. So they’re getting the shape of the poetic sentiment into their oral cavity. It’s been up for 16 weeks and hasn’t been graffitied or complained about. I’m hoping someone does graffiti this pristine artwork at some time. I don’t quite understand why not.

KG Too sacred?

RL When I say “we” I’m referring to the assistance I receive from Bartholomew Rose. He works for me in the studio three days a week. He’s enabled me to undertake a wide range of physically demanding installations over the last five years. He’s a Scrabble expert and a very valuable iterary companion to have.

KG Back at Millers Point…

texting

RL The Index of Kindness takes up from where the Index for the Homeless leaves off. Kindness is the thematic umbrella I am working under at present. The idea is to think about the Millers Point precinct and a number of the public buildings in the area as the next surfaces to publish onto in the name of “the public house”. We’ve been arranging for the Millers Point community to participate with their own “texting.”

KG You mean mobile phone texting?

RL Not really. The people there say, “We don’t have mobile phones and we don’t have computers.” The issues of information and activism are articulated differently in that community. They say, “you’ve gotta give us proper messages. You can’t just think digitally and expect us to read your emails.”

KG How do you work with these communities to get their “texts”? Do you interview people, make sound recordings?

RL At the moment we’ve been going through the process with the Darling Harbour branch of the ALP and the National Trust and Tenants’ Union. The branch meets monthly in the Garrison Church. For these interviews I’m working with Jo Holder, a well known curator, writer and activist. I guess a local ALP branch can be like a little church itself. It’s a conduit of informed opinions where like-minded people are motivated to come together politically. Most of them are or have been activists too. They’re a group of very articulate and socially motivated people. They’ve recorded a lot of the things that have gone down with state government’s dealing in that region. The Millers Point residents have often been described as a traditional inner-city community. The impact on Hickson Road with the new Barangaroo development at East Darling Harbour is monitored by this fragile community very closely. The history of activism in The Rocks goes back to the Green Ban days when the BLF led by Jack Mundy, Joe Owens and Bob Pringle were there on site saving The Rocks from demolition for more office towers. This community has seen it all and has learnt to deal with all the difficulty of state and council bureaucracy. Now the fight is to protect the community itself including much of the residential properties for low income housing.

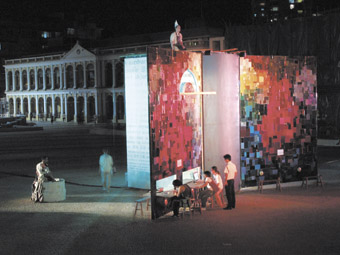

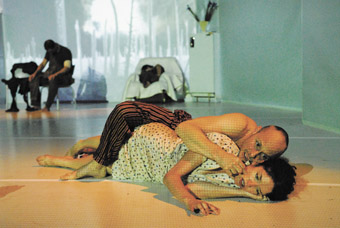

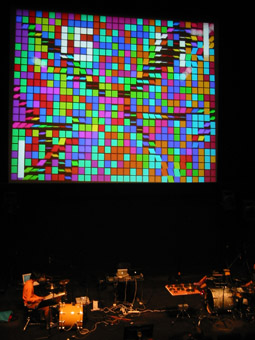

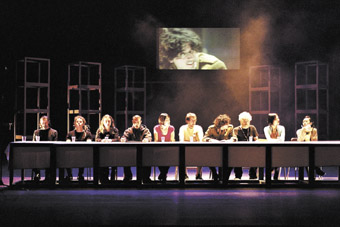

An index of Kindness, Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, 2008

courtesy the artist

An index of Kindness, Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, 2008

municipal signs and other objects

In Lewis’ most recent show at Chalk Horse in Sydney’s Surry Hills, the gallery was hung with flags stencilled with words from Nathalie Sarraute’s play Silence. Below, on the floor and plinths, everyday found objects had been painted with red and white stripes and markings, making the gallery-goer doubly attentive—to where they trod and how they were regarding the art.

KG In your latest gallery show at Chalk Horse there’s your usual play on words, in the form of flags. There are objects as well. Where do these fit in the scheme of things?

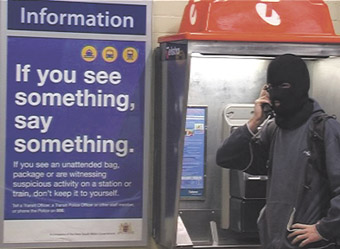

RL I guess I’m using the gallery to test out some of my outdoor optical and spatial systems. I’ve been considering the sculptural objects in the show as decoys. Leading up to the Chalk Horse show I was studying maritime signage. The navigating tools that ships use on the harbour. I realised there’s a language for signs out there, a municipality of water and land signals. I’m very interested in the municipal sign and seeing where an artwork can transgress the polite internal boundaries of cities and streets and art galleries. One of the Chalk Horse panels is being prepared for reinstallation at Abraham Mott Hall in Argyle Street, Miller Point. This stencilled timber work called Conrete Poem II will be added to a sequence of other panels called Euphemisms for the Seafaring Nation. I’m making these things as modular constructions so they’re adaptable and relocatable. At Chalk Horse, all the objects on the ground operated as warnings so that visitors won’t trip over. They’re like the rocks of Mer in the Torres Strait. Eddie Mabo identified a bunch of rocks around his Island of Mer as being the markers for the language or community zones. I thought that’s a very useful message for all Australians to start to recognise. We need to identify our environments with objects set out as markers. These are the municipal markers that translate a whole bunch of security/insecurity issues that control the movement of society. I was in Singapore last year. To me Singapore is a remarkable, urbane area but it feels as though it is adapted from the City of London. It’s the municipal aspect of London that modern Singaporean politicians adopted to their equatorial zone in a number of ways.

KG What did you do in Singapore?

RL I was actually looking for garbage. I thought, here’s a place where you can’t have long hair, you can’t chew gum, what can you do? Obviously everything is very clean and modern there. So I started making work about the garbage—on the streets, in the countryside or washed up on the beach. I began to examine parts of the island that weren’t stereotypically clean and modern. Jonathan Jones and I picked up pieces of junk as we drove all around the perimeter of the island state. We went out to the rural areas and coastlines. We reached the industrial area Jurong where an army of cheap contracted labour from the Indian sub-continent are imported and housed. We did a week of urban fieldwork in a hire car last September. It was the sense of island containment that we decided to study.

KG So what did you do with the garbage?

RL I stencilled messages taken from An Index for Redundant Expressions which I’d assembled there. It’s a set of 45 aphoristic tautologies. Found phrases or ready-mades, for example: “9. earlier in time, 16. an honest truth, 32. a pair of twins, 1. an actual experience.” I inscribed these onto pieces of garbage. Then I placed these messages back into the piles the rubbish came from and made a photographic record. This formed an intimate poetic puzzle. I wanted to leave messages for people anonymously. I avoided the fear of arrest by photographing the evidence before and after I removed it. Sometimes I kept elements of the garbage to paint an abstract pattern on it—with red and white or black and white stripes painted in gouache. We arranged sets of these garbage ‘props’ for the large exhibition we assembled at Post-Museum. These displayed redundant expressions accompanied by three distinctive suites of work under the title of An Index of Kindness. There was An Index of Emotions which is an audio construction formed from vocal performances I made with Amanda Stewart. The spatial affects in audio were collaged by Rik Rue. Then the Index of Line was a wall drawing executed by Jonathan Jones.

Jon photographed the Singapore coast and shipping channels. He drew with meticulous precision the contours of most of the landscape of the island and parts of Malaysia in the distance. The drawing encircled the three rooms forming a semi-abstract design on the gallery walls. He just kept layering his drawings so a sense of landscape appeared cloud-like and hovering which was a really interesting anti-territorial take on a visited place.

The Index of Silence involved the stencilled flags you mentioned before, that’s a transcription of Nathalie Sarraute’s play Silence. The red and black flags, suspended low from the ceiling, distorted the volume of the space altogether. We significantly controlled the volume both spatially and directionally by designing the sound. The speakers for the vocal collage were hidden above the hanging textiles. All this was pretty emotionally charged, with the sound of tears and anger. The sound of Amanda and I appeared and disappeared as the sound collages Rik Rue devised panned around the rooms—the audio was kind of spooky there!

Singapore is a place of finite politics so I decided to make a banner. Apparently the making of political banners has to be authorised in Singapore, so I made a concrete poetry banner called QUOTE where I took a line from the Indian writer Ashis Nandy that said, “It was a strange mix of love and hate, affirmations of continuity and difference, nostalgia and a sense of betrayal on both sides.”

The redundant objects were diversions to slow down the audience. I don’t want people to consume exhibitions quickly. At times our signs seemed odd. My favourite object was the coconut. A truly beautiful painted object. A small leaf began to emerge during the exhibition and it just kept enlarging, breaking through the husk. The shell was painted with black and white stripes, then this little green sprig appeared. We found a broken shovel left by the builders of the gallery. We painted it along with a frame, a chair a rock and ball, a stick and a tree branch. A lot of these ‘municipal’ signals were stimulating to look at without being burdened with the values and meaning of a grand allegory. I liked the way the owners called their gallery Post-Museum. A sort of dissident location in itself.

the artist begins

KG When did you become an artist?

RL I went to Sydney Boys High School. One day I went up to the art room and a friend of mine was throwing on the pottery wheel. I became totally mesmerised how that form came up out of his hands and fingers. I loved the slithering plastic action of the clay that formed in his hands. I went straight out and bought a bag of clay that afternoon and made a sculpture, not a pot as such. That’s where it all began. My brother is a photographer and my cousins are musicians and painters. Nicola Lewis played the violin in An Index of Horses which we made as a performance-for-video at Chalk Horse. I sort of come from a Jewish artistic family, a tribe of mercantiles and artists. According to the painter Cedric Emmanuel our earliest Australian relative was Michael Michaels. He was a forger who was pardoned in 1809 and left Sydney returning to London where he started an orchestra. We’ve always had painters and musicians in the family so making things seems natural to us.

KG You have quite a collection of pottery here in your apartment.

RL I’ve procured these jugs to make an exhibition. I‘ll probably call this The Index of Forms. I’m focussed here on the anthropomorphic conditions that are related in the forms of the jug. These vessels are built with a foot upon which they stand, and a belly, where the bulk of the contents is stored. They have handles, necks and lips. That means they have at least five different physical attributes relating to the human form. I’m thinking of a book which indexes the shadows they cast set alongside the silhouettes and profiles from the bodies of dancers. I’m interested in the double nature of the cast of shadows. I would love to generate a text from a series of conversations with a man who has Alzheimer’s Disease. When we talk he often tells me things in a manner I think of as neo-Dada poetry. To everyone’s surprise we have a terrific time sitting there talking with gusto. If I could record his sayings, write them down in the form of our dialogue it could have an interesting and enabling affect. He’s been a journalist all his life; so the idea and its written form is like a game on his tongue. That’s a nice thing to try and share. Pottery has always been a really interesting through-line for me.

KG So you threw pots yourself?

RL I studied Ceramics at the Sydney College of the Arts with Bernard Sahm and Mitsuo Shoji, both very interesting artists. It was difficult for me physically but I needed the tangibility of clay.

At that school I came into contact with the composer David Ahern in the Sound department. David was a total radical. A really heavy drinker but strangely charismatic and he was wonderful to a small band of loyal students. He’d been working with Cornelius Cardew in London and for two years was a personal assistant to Karlheinz Stockhausen. He came back to Sydney in the early 70s and among other things he ran a Sunday new music workshop out of Inhibodress Gallery. That was the group called Teletopia and AZ Music. Tim Johnson and Mike Parr and Peter Kennedy ran the avant-garde concept gallery the rest of the week. But on Sunday the experimental artists ran an open studio where trained and untrained musicians joined together to perform music. Although I wasn’t involved in those early years I’ve been very interested and was highly motivated and inspired by Ahern’s practice. He was just at the end of his teaching life when I came in contact with him. But it was wild. It was recklessly terrific. I thought this is really what art’s about. Because it was a language made of sound and music, and I studied music throughout high school and my cousins were practicing musicians. Someone like Ahern became strongly influential. In a sense David was the first in a string of “tormentors” I got to know outside of the normal structure of the art school pedagogy. Ahern was very discouraging of my interest in ceramics and always urged me to paint and draw. Soon I began making sound drawings on sheets of cardboard using charcoal and white chalk.

KG So this opened up the idea of there being a number of means of functioning of an artist.

RL Yes. Ceramics gave me a sort of classical education, which I may not otherwise have received in such a serious avant-garde art school. I did a paper on drawing in ancient Greek ceramics. It was an interesting medium for discovering the function of mythology and literature of the Greeks. Then I studied Asian architecture and the correspondences with early classical sculpture. I got a better grounding in architecture that way, which has been infinitely useful. For some unknown reason I never did study painting at art school. I think it would have been physically easier for me. In 1984 I was expelled from Sydney College of the Arts. That was pretty demeaning—it really wasn’t my fault. I also had been expelled from Sydney Boys High School in 1978. Perhaps both these rejections shored me up as a kind of outsider in art—in that I seemed able to miss out on certain unnecessary things exactly at the right time.

KG It didn’t inhibit your progress as an artist.

RL No, it freed me up really.

the artist as curator

KG What did you do then?

Ruark Lewis, A Babel Reading-Machine (2005)

photo William Yang

Ruark Lewis, A Babel Reading-Machine (2005)

RL I left art school and was lucky that Ann Berriman asked me to perform poetry at the Biennale Readings she organised at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. During the 1982 Biennale a group of contemporary Australian poets were scheduled to make readings at the gallery. Anna Couani was invited to read. She realised that the Biennale paid the international artists fees to appear but the organiser for the poets had no arrangements in place to pay the poets fees. Organisers of Sydney poetry readings have been notorious for paying low fees for poetry readings, forcing the poets into what was basically an amateur arrangement. I don’t know why the Literature Board didn’t form a rates schedule. On the gala opening night of the Biennale Couani organised a protest on the steps of the state gallery. It caused such a fuss that a small fund was released immediately from the Literature Board to pay fees for the readings. I thought Anna’s fighting spirit had done a lot of good. She’s a terrific writer. In 1985 I managed to convince the Gallery to start another program of readings, for younger writers and new media artists. Some years later we were able to commission a setting of Couani’s The Harbour Breathes which was brilliantly performed with projections by Peter Lyssiotis and sound designed by Rainer Linz. I thought if you’re going to be a curator, you might as well be a producer and procure the best fees for artists commissioned or programmed to perform in a state gallery.

Initially I worked on the younger poets’ series. We had a six week season of readings. But perhaps even more interesting was when Emmanuel Gasparinatos agreed to join me and he programmed a new media event in the theatrette called Sound Alibis which included 14 artists. People like Rik Rue, Warren Burt Sarah Hopkins and Vineta Lagsdina participated. There were Super8 films and sound works and live performances. Burt assembled his massive tuning fork installation that reverberated through the gallery’s Victorian courts. That was truly spectacular. The program continued to be modelled along those lines of new media and spoken word and poetry for another five years. Those events gave a lot of production confidence to a younger generation of artists presenting to a general public in a state gallery.

I developed the program further the next year with the poet and scholar Martin Harrison. Martin was interested in the writer/performer as live presence, in creating a kind of listening room atmosphere. He was at the ABC at the time doing his Books and Writing program. We’d met at the first Premier’s Literary Awards. This began a really successful curatorial collaboration. Our more substantial programming strategy evolved quickly and it made the AGNSW the stage to a wide range of writers and musicians, composers, filmmakers, visual artists, performers dancers, radiophonic composers. I worked on promoting the programs and quickly built up a large audience. I kept working out ideas of how to get the most radical types of experimental art out to the widest audience possible. I thought if you’re going to compete for funding from the Australia Council the key would be large and consistent audiences. I remember heading off to lots of radio stations with cassette copies of Kurt Schwitters’ Ur-Sonata or Ania Walwicz reading in her remarkable voice—even radio stations like 2GB would give me five minute interview each season.

KG Virginia Baxter and I did a misguided tour for gallery goers, Small Talk in Big Rooms, in 1991 for a Jonathan Mills-Martin Harrison program.

RL These big museums needed us to animate the place. And we need them because audiences like that sort of place to hang out in. People in metropolitan centres want to go to unusual events all the time. They’re not scared of the weird but they don’t go to off-beat venues easily. I was keen to work at the grass roots level. I saw it as an act of anti-elitism to promote the radical art to a willing public.

We’d always program an establishment decoy in our series. The Big names, poets like Judith Wright, David Malouf or Les Murray. They helped to attract the very large crowds for us. We programmed the soprano Elizabeth McGregor singing the Margaret Sutherland settings of early Judith Wright poems alongside the relatively unknown work of Allan Vizents, William Yang, Ania Walwicz or Jonathan Mills. I remember the afternoon when poet Gwen Harwood and composer Larry Litsky presented their recital—a very memorable and stylish event. We maintained the idea of airs and aria as the program through-line. It was very demanding curatorial work. At the end I wanted get back to my own studio practice. I curated for four very intense years and helped produce well over 200 performances. I was pleased that we could raise professional fees and standards and develop funding arrangement that crossed over in a completely new way.

KG Writers-in-Recital happened once a year?

RL Yes. Each year as a one-month season during either the Biennale or the survey exhibition called Perspecta. In 1991 Jonathan and Martin took over and tried to make the program run as regular bi-monthly event.

KG Which year did you leave?

escape to melbourne

RL In August 1990 I escaped Sydney. I headed off to Melbourne, I travelled overland to Wollongong to watch Jaffa and Richard Moore perform Kurt Schwitter’s Ur Sonata alongside Andrew Ford’s music theatre piece Icarus, with a Barbara Blackman libretto. I travelled to Canberra and stayed for a week. You know, sometimes when you work too hard you become emotionally breathless and can’t get your heartbeat back in the right pattern.

In Canberra I found a copy of TGH Strehlow’s Journey to Horseshoe Bend. It’s biography/autobiography about the death of his father, the missioner Carl Strehlow in Central Australia in 1922. I started reading what turned out to be a transformative book for me. I felt this epic story could somehow be adapted either as a film or an artwork. I headed off with that text in hand to visit a Sufi retreat at Yackandandah. It was the off–season so I slept in and revived myself there for a couple of weeks. It was a good occasion to go walking in the backblocks. I followed the fence lines and picked up pieces of wire and made an installation under the verandah of their building. Those wires looked like Arabic calligraphy set out across the walls.

KG Was this the beginning of a particular kind of work that you’ve continued?

RL I was “texting”, so to speak, a bit earlier. Looking at the work of Juan Davila, Imants Tillers, Robert McPherson and Peter Tyndall who worked with inscription in their painting, I wasn’t totally convinced by what I saw. From a literary perspective it seemed to lack the poetic content I’d been seeking. That’s the sort of depth I was looking for in my own study of language. Their work was high art and powerful and of considerable museum scale. But I didn’t think there was the depth that a baroque field vision could offer. I wanted to lay in poetic lines from poets I was reading at the time, like Rilke’s Duino Elegies. I wanted to actually enact it as a trace. At the time I was working on musical and sound transcriptions in the form of drawings. That’s how I’d begun texting into works and making abstract cross-overs from one art form to another.

I made diagrammatic drawings of sound works too, starting with acoustic music and then I experienced the work of the Sydney composer Robert Douglas. He was making large-scale works on the Fairlight CMI. I wanted to make drawings tracing his computer music. I was realising that I could make art too, that I didn’t have to curate. It was a bit of a crisis. I could have made an entry into a professional career as a curator and been paid a salary at that time. But I realised that I could also do these other perhaps more creative experimental things, and that’s what I was interested in.

That year I went to Melbourne and stayed with Paul Carter. We met there to look at Joan Brassil’s retrospective at ACCA in September 1990. We’d formed a sort of group Martin Harrison, the director Peter King, Jonathan Mills and Paul. Mills called us the North Caufield Light Opera Company. I wanted to meet and talk to people like Warren Burt, Chris Mann, Vineta Lagzdina and Rainer Linz who was publisher of the magazine NMA. Melbourne had been a radical birth place for new media arts and experimental music at the Clifton Hills Community Music Centre. Rainer Linz and John Jenkins’ book 22 Australian Contemporary Composers anthology was the sort of curatorial guide I’d been looking for at AGNSW. There had been little like that sort of thing operating Sydney. The Melbourne discourse was quite advanced and very anarchic. By the time I arrived, I’d been “corrupted” by the newly acquired Strehlow material. Paul Carter was working with considerable consistency making his early radiophonic creations with people like Andrew McLennan at the ABC. That was the era of the ABC’s radio atelier program Surface Tension (1980s) and later The Listening Room. Carter had been editing the Age Monthly Review which we’d all contributed to over the years. This was an artistic atmosphere I called ‘my university’.

KG How long did you stay?

RL I kept going. Visiting friends, sleeping on floors and cooking for them, entertaining people, just being there like an artistic vagrant. I loved Melbourne. I’d go down every few months. Then Grazia Gunn was directing ACCA and she offered me a solo exhibition. I’d only done one or two solo shows (19 musical transcription drawings and a language transcription exhibition in Sydney). That ACCA gig was my big calling to come. I worked on it solely for two years.

KG What did you do?

RL I formed an exhibition in three parts. I finished the Robert Douglas transcriptions, which ended up being 48 metres of extended drawing. The 48 panels occupied the Lotte Smorgon Room at the old ACCA in Melbourne’s Domain. There were studies of Douglas’ Homage to Bessemer, and the 48 Alpha Solstice drawings. That was the ‘listening room.’ I made a room of literary transcriptions based on the French newspaper Le Monde. I’d been in Paris in 1991 and I found a way to look at the demarcations between the generating forces in commercial print media. It was a simple critique of how photography, journalism and advertising worked in concert on the pages and how that formed the capital which is the motivation for a daily publication.

KG So you reframed the material in a way?

RL It was a direct response on to actual newsprint. This work mirrored the time Rupert Murdoch of News Limited was closing down his newly acquired Fleet Street press and moving The Times to their robotic Wapping media factory. My drawings were a deconstruction of newspaper, a week of newspapers with drawings highlighting the spaces in between the contents. In this space I made a set of transcription drawings based on a group of bark paintings traced from the AGNSW and the Australian Museum. What interested me most were the painters from Yirrkala. These archival works had been collected by Charles Mountford in 1948. I was interested in those objects for all sorts of problematic ethical reasons. These paintings had been acquired as a form of scientific information during the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. I made a kind of funerary drawing from Mountford’s ‘data.’ I was making a ‘drawing’ that covered up the painted iconic blocks on the bark paintings. By drawing a kind of reversal all that remained was the grids between the pictograms. The ‘lines’ were just the raw paper left over in the reduction. The black rectangular areas were simple burnished graphite surfaces. I transcribed a set of 12 bark paintings and called the results The Silhouettes.

KG What is involved in this transcribing process?

RL I took sheets of mylar plastic and placed them over the top of the objects. With a texta I traced the regions. I drew around where the picture block sat in the case of the bark paintings. I’ve also made similar transcriptions from the collages of Kurt Schwitters at the Sprengel Museum in Hannover. The skeletal forms of the original works are recorded from the bark or collages. These lines represent the directional modality defined in the original by the artist before the readable pictogram is put into place to tell their story. I am attracted by the structure of those schematic intentions.

So that’s what the first exhibition was—fairly esoteric too. It was part of Melbourne Festival in 1992. Melbourne was into high postmodern and neo-expressionist painting then, and along comes an incredibly cool minimalist show with regional underscores. It was shown there for a lengthy 14 weeks.

KG It would have excited the high theory crowd.

RL They mostly ignored it! It was an incredible experience to be given such silent treatment. Maybe that’s what happens coming from Sydney and being 32 at the time and having the top spot at ACCA during a festival season. But I made a lot of terrific friends through that project. I asked the composer Keith Humble to open the show.

KG So you were on a path; were you immediately picked up elsewhere?

RL No. It was ‘difficult’ work and it was commercially ignored. The next two years was fairly quiet and contemplative. A few dealers made comments. I remember George Mora liking the newspapers drawings very much but he said they were unsaleable. Charles Nodrum has always been very keen. I like the fact that you can work “fairly privately” in Australia. I always understood that experimental art would be ignored by the local art cognoscenti and that the avant-garde was taken up by the academies that could easily canonise it in what I regard as a pseudo international context.

the experimental realm

KG So you’ve seen yourself very much in the experimental realm rather than from an established avant-garde position?

RL Yes. I just thought there was more interesting dialogue between artists and forms in what is experimental.

KG There’s a public conflation between experimental and avant-garde usually. People don’t make the distinction

RL Ahern made the distinction from the outset: Schoenberg and Stravinsky, then Cage and Boulez. I’d been wanting to make the distinction. I tried to make the distinction at the AGNSW and we could model it on the stage with the Margaret Sutherland and Judith Wright work for instance. The music and writing was avant-garde in 1943. On the other hand, placed right beside that were the extreme writings/performances of Ania Walwicz. We could form those kinds of critical juxtapositions in the museum. Walwicz has always been remarkable to watch, or read on the page and then she’d do these haunting performances. Those writings correspond to the paintings she makes also—like dream sketches in oil paint. It’s a modest and manageable practice but a fantastic way of working with things. The Sutherland setting of Wright is probably known by only a small group of musicians and historians today. Programming a local rarity like that, with a big shiny Steinway on the stage was a different way of analysing the structural differences of both these tendencies.

KG So the experimental for you represented various means of working whether through text or image or performance or film or whatever. What is the essence of the experimental as opposed to the avant-garde?

RL Well to me it’s a living force with the musicians or performers. Not exactly being a musician myself but having studied music at school and in association with Ahern and people like that I focussed more and more on structures rather than expression or evocations. I wasn’t really attracted to the technological in new media as a means for hand-crafted works. I’m happy using low tech tape recorders, using video to form a document of a process. I didn’t know how to use a computer for a long time. I was lecturing in the new media lab at SCA but didn’t even know how to turn a computer on. The students were eagerly making CD-ROMs at the time. I was teaching what I thought of as a production management course—almost like a project manager on an architectural site. It was the expansiveness, I suppose, of the experimental realm, the idea that art and production could take on other forms in constant flux and I could rewrite them that I found stimulated my thinking about experimental art.

And there was a correspondence to this work outside of Australia for my artistic friends. John Cage had picked up on Chris Mann’s work and set it for an opera. What I find most interesting in writers like Mann and Walwicz, and others Javant Biarujia, is the certainty of their regional voice. I guess you could say that about Gerald Murnane too. To me this is both political and psychological. In certain ways I understand their writings operate as a kind of artistic resistance. It’s about being in this place in the work but in very interesting and surprising ways. Carter’s writings too had taken the regional condition and re-examined it in books like The Road to Botany Bay or his Italian book called Baroque Memories. I think there’s too often an identity crisis in the Australian avant-garde. The constant need it faces to be academically relevant. To me that leads to conformity. Isn’t that what the underlying anxiety of cultural cringe is about? But with the experimental, there’s a sort of fraternity that I like, keen about reading through each other’s work, reading the sound waves that each artist arrives with. I found it highly attractive that when you went to Paris someone was there that you could plug into right away and you felt very much part of what is going on. I went to Paris and began to work with Kaye Mortley on the Nathalie Sarraute book. That was remarkable shift. To be part of a cohesive living culture that remained in nature to that place as well.

KG When did this happen?

RL 1991. I made the Le Monde drawings for my ACCA show while I was in Paris. I’d met Kaye Mortley and Rene Farabet here in Sydney. Martin Harrison was a friend of Kaye’s. All sorts of interesting people came together at the Harrisons’ house. The dinners often went until dawn. When Rene and Kaye came to Australia a sort of sound circle developed around them and the Listening Room at the ABC and at UTS. It was formed by Virginia Madsen and Tony MacGregor and Martin. Rene Farabet was director of the radiophonic atelier program called France Culture, so there were significant cross-overs with people working here. Kaye had been a pioneer in the new radio at the ABC—the days of Radio Helicon I remember so well.

transcription & translation

I went off to Paris and had the best time of my life. I felt like I could walk all over that city. I wanted to make an artist’s book with Kaye, to try to form a radio score into a book form. I was really interested in how her radio scores appeared to be arranged to form a depth of field in audio terms. That’s a form of literature that doesn’t come outside of the production room very often at all. She’d published a work in a Sound issue (number 31), of the Australian journal Art & Text which looked fascinating on the page and I thought, there could be a whole book possible relating her many and various creations for radio. But Kaye said we should ideally work on the play Pour en Oui Pour en Non (Just for Nothing) by Nathalie Sarraute. She’d translated that work for radio—the ABC did it with Arthur Dignam and Barry Otto. Perhaps I was a little disappointed not to work on her scripts, but when she described the play I immediately had a vision for setting the players’ script marked out on the page in different colours. The colour would navigate the reader through the text like a graphic score. I wanted to run the lists across the page so it was justified left and right and formed as modern prose would work. That’s a better way to read it and easier for the actors because they’ll know how much material is coming up from the blocking of the colours.

KG I remember seeing it at Sarah Cottier Gallery in Redfern.

RL It was ignored again.

KG It was beautiful.

RL Thank you. Andrew McLennan launched it (I think he produced it at the ABC for Radio Helicon) and he did a wonderful rendering of the idea of the play that afternoon. We got a small but knowing audience for that exhibition. And we had Nathalie’s voice present in the installation! We went beyond the play. Nathalie lived to 99. When she died I wanted to bring her voice into the installation. Kaye had made a supplementary audio work where Nathalie was speaking about herself being photographed, and as a child, and there was a statement about self perception—the paradox of growing old and not growing young.

When we were making the book, I asked Kaye Mortley if she would construct a sound piece as an idea for an installation of the book pages bringing the presence of the author into place. One of the tricky parts about working in Australia with Kaye was that people didn’t seem to understand the significance that the translator represents alongside that of the author. Her relationship with Sarraute was so intimate. And Nathalie loved the English language, so it was in every way an ‘authentic’ translation, a collaboration between the two of them. That art work started in 1991 and it turned into a 10-year project. A lot of my projects have been constructed over a long period of time. Perhaps it will return.

RAFT (2005), with Paul Carter, collection Art Gallery NSW

photo Ian Hobbs

RAFT (2005), with Paul Carter, collection Art Gallery NSW

the raft journey

KG Was RAFT a long process?