Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

Venus, Natural Crystal Chair, Tokujin Yoshioka, from the 21_21 Design Sight show Second Nature, directed by Tokujin Yoshioka, Tokyo

photo Masaya Yoshimura

Venus, Natural Crystal Chair, Tokujin Yoshioka, from the 21_21 Design Sight show Second Nature, directed by Tokujin Yoshioka, Tokyo

to all our readers

have a cool xmas and

a calm new year rest

readying yourself for

the high dramas and

the great art of 2009

the editors

Image: Venus, Natural Crystal Chair, Tokujin Yoshioka, from the 21_21 Design Sight show Second Nature, directed by Tokujin Yoshioka, Tokyo, Oct 17,2008-Jan 18, 2009. See page 15 for a report on this fascinating bio-art exhibition. www.2121designsight.jp www.tokujin.com

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 1

© RealTime ; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

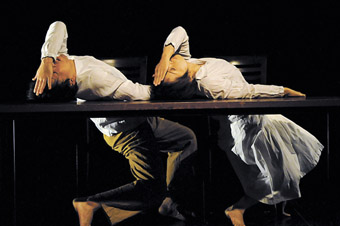

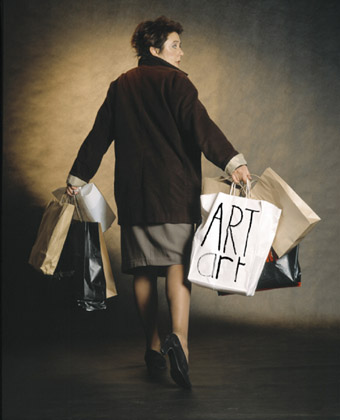

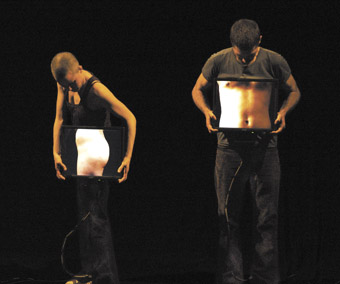

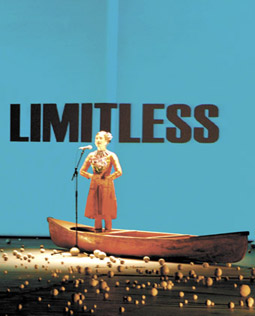

If I Sing to You, Deborah Hay Dance Company

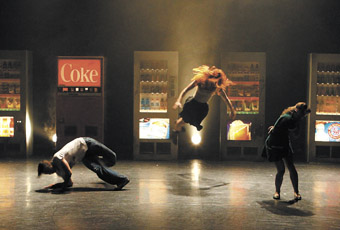

IN THEATRE, THAT OL’ BRECHTIAN ALIENATION EFFECT IS ABOUT AS CONTEMPORARY AS IAMBIC PENTAMETER. IF THIS YEAR’S MIAF WAS ANYTHING TO GO BY, THOUGH, AESTHETIC DISTANCING IS THE BIG THING IN DANCE TODAY. KRISTY EDMUNDS’ TIME AT THE HELM HAS ALWAYS BEEN MARKED BY A STRONG CHOREOGRAPHIC FOCUS AND IN HER FINAL YEAR AS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR SHE PRODUCED A PROGRAM WHICH BOTH SHOWCASED THE DIVERSITY OF DANCE AT THE CUTTING EDGE WHILE MAINTAINING—PERHAPS INCIDENTALLY—CERTAIN COMMON THREADS INTERWOVEN THROUGHOUT THE FESTIVAL.

From Deborah Hay’s “counter-choreography” to Chunky Move’s literal interrogation of process, the dance works on offer variously deconstructed, reinvented and defied conventional expectations of the form. Of course, frustration as an aesthetic goal has its obvious limitations—in asking an audience to think about dance, the sheer wonder of performance can slip away in favour of a purely intellectual appreciation.

Wendy Houstoun, Desert Island Dances

wendy houstoun’s desert island dances

The perfect contrast in this sense would be Wendy Houstoun’s coolly rendered Desert Island Dances and the vast, impenetrable Sunstruck by Helen Herbertson and Ben Cobham. Houstoun’s solo performance was an oral meditation on the history of movements she has acquired or been given over her long career, a cerebral exercise which purposefully prevented the audience’s immersion in its physicality by constantly pulling back to discuss it. Sunstruck, on the other hand, was an event of pure dance that challenged its spectators’ ability to rationally understand it, instead creating an intensely overwhelming experience that could not be reduced to words. In this sense, Sunstruck truly merits the term ‘sublime’, a word overused in arts writing and seldom deserved.

Houstoun is a leading artist who has worked with an enviable range of fellow dance- and theatremakers, including Lloyd Newsom’s DV8 and Tim Etchells’ Forced Entertainment. Etchells’ influence is especially evident in Desert Island Dances (and as a side note, it could be argued that Forced Entertainment has been the most profound influence on a massive range of Melbourne theatre at the moment, too). Desert Island Dances relentlessly questions the act of performance-making and liveness; like Forced Entertainment’s Bloody Mess, it attempts to invoke a sense of immediacy and spontaneity while actually maintaining an incredibly tight structure and logic. Houstoun talks her audience through a series of speculative moments: what if this happened? And what if I did this? And what if I then did this? It all seems loose, off-the-cuff, a performance always on the verge of beginning. But in this constant deferral, Desert Island Dances becomes a very cool work. Houstoun appears a fascinating dancer who only occasionally allows us to witness her, well, dancing. Moreover, the restrictions of the work’s solo nature become evident. It’s difficult to create a dialogue around dance-making when there’s only one voice to discuss it.

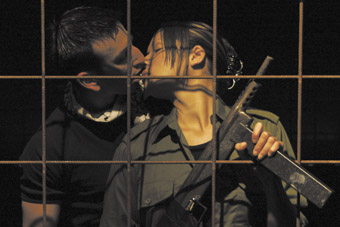

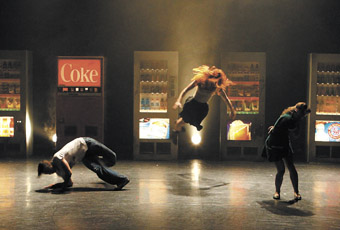

Two Faced Bastard, Chunky Move

photo Chris Budgeon

Two Faced Bastard, Chunky Move

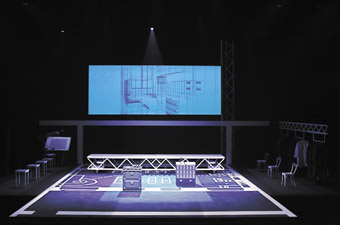

chunky move’s two faced bastard

Chunky Move’s Two Faced Bastard explores similar territory to far more sophisticated effect. A large playing space is bisected by a curtain of vertical blinds; the audience is split in two, one half on either side. The work we see depends on our placement—on one side an abstract, contemporary dance begins while on the other a panel discussion on performance occurs. There’s a certain bleed between the two from the outset. The gently swaying blinds allow infrequent glimpses of “the other side” while the microphoned forum can be heard in both halves of the space. And soon enough, the collision of worlds becomes more obvious, as performers enter one another’s space and influence their new surroundings. Brian Lipson interrupts dancers to question the meaning of their movements; a relationship begins between dancer Stephanie Lake—who is situated on the “dance” side throughout the performance—and actor/dancer Vincent Crowley, who begins as a pivotal figure on the discussion side.

As things proceed, the engagement becomes more hysterical. At one point performers suit up in robotic battle outfits fashioned from boxes and polystyrene and charge through the curtain to wage war on their counterparts. At another, the audience is offered the chance to cross the stage and see what effect a new perspective will provide. And at no point are the performers able to step offstage; with no wings to speak of leaving the playing space simply means moving into another.

What all of this results in is a wonderfully dialectical form of performance. It is the presentation of conflict—between action and interpretation, dance and theatre, body and mind—which creates a third space of meaning. For much of the work we are acutely aware that we’re missing out on something, that our position only affords access to half of a work. But when, finally, the curtain pulls aside and all of the performers are made visible across the space, we realise that this concealment is itself an integral part of theatre, and that what we have been watching all along has been a single, coherent work, not two distinct productions which intersect at vital points.

Two Faced Bastard’s duality is probably due to the differing interests of its creators—it feels at times to be an exchange between Lucy Guerin’s focus on the moment of dance, on dance as a form of presence, and Gideon Obarzanek’s more conceptual explorations of the framing of works. It’s a deeply intriguing, and often very funny exchange, and it’s also apparent that the performers themselves have been crucial to the formation of the work.

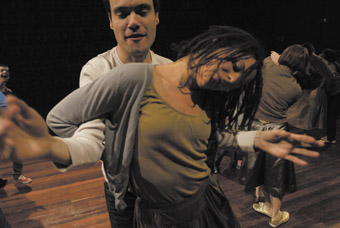

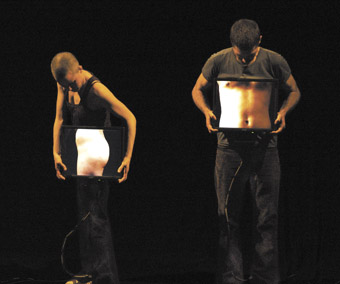

Corridor, Lucy Guerin Inc

photo Jeff Busby

Corridor, Lucy Guerin Inc

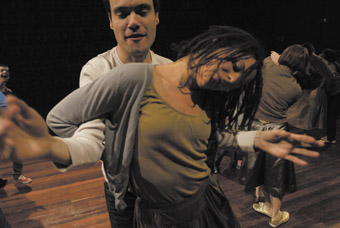

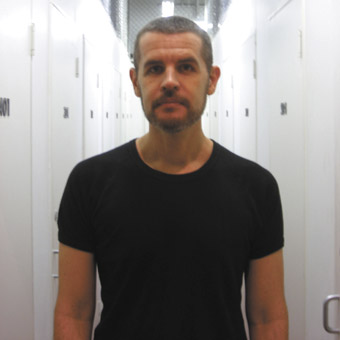

lucy guerin inc’s corridor

Several of Two Faced’s dancers also contributed to Guerin’s Corridor, a work that more closely adheres to the ongoing investigation of the theme of communication which has marked much of the choreographer’s output. Here, it is the way in which movement itself is communicated from one body to the next which is put into relief: set along a narrow strip bordered by an audience row on either side, the dancers ‘pass’ motion to one another in a variety of ways. Instructions are given via microphones, MP3 players, whispers and written text. Spontaneous choreography bounces back and forth along the space as dancers imitate one another’s moves; and the signal distortion increases as dissimilar bodies hastily attempt to replicate a particular phrase created by a distant figure.

Like Two Faced Bastard and Desert Island Dances, Corridor is dance about dance, in this case the process of instruction and translation of motion. It also serves up many memorable sequences of actual movement, preventing it from becoming a navel-gazing exercise or a piece which undermines itself in order to provoke. It’s smart, witty and very rewarding.

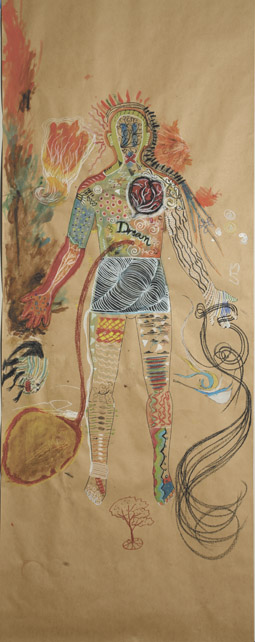

deborah hay dance company, if i sing to you

Deborah Hay occupies a different stratum entirely: the veteran US choreographer has created a vocabulary of dance that speaks to her contemporaries while remaining utterly distinct. She challenges her subjects to unlearn the inherited movements of their history; to become aware of the body’s momentary existence in any particular spatial and temporal environment; and to respond to the cues sent by this body in every instance. Hers is a kind of cellular choreography, and she asks her dancers to try to sense the signals of the trillions of cells which make up a single human figure. She has written extensively of her craft, and the writing is often obtuse and provocative in its esoteric nature. But it was a privilege to witness Hay’s theories in action, and If I Sing to You is a difficult but unforgettable experience.

The six dancers themselves appear a kind of sluggish organism as the work commences. It’s hard to delimit a particular starting point as they stand vacantly while the audience take their seats, and no conventional cues—the dimming of house lights, for instance—occur to mark off the performance. They stand closely, swaying slightly, surveying their surroundings. We are not watching six bodies performing. We are watching bodies ageing, evolving, existing. They may make noises. They may shift a foot, or lean, or react to another’s leaning. They are listening and watching.

Over the next hour, these dancers don’t dance. At least not in a recognisable sense—there is much movement, but it is startling in its unexpectedness. As trained performers, of course, these movements are not naïve, but are instead a kind of physical version of the negative space of visual art, the physicality that is made absent by choreographic convention. Hay forces her audience to think about dance not by telling us to do so—as does Houstoun’s work—or by explicitly exploring the problematics of thinking about dance, in the way that Chunky Move succeeded in doing. Hay simply does something so different that one’s preconceptions need revising.

If I Sing to You’s dancers are all female but decide upon the gender of their performance shortly before it begins. Some will dress in male attire if they choose, and the result will apparently affect the dynamics of the performance. Apart from a hilariously oversexed routine in which a facially-haired performer indulged in some animalistic thrusting, this conceit didn’t really contribute much to the performance I witnessed. This is a minor quibble, however. For a newcomer to Hay’s work, this piece was confounding, brilliant and impossible, without any dressings.

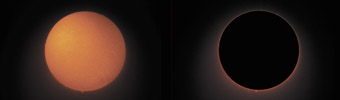

helen herbertson & ben cobham, sunstruck

And so to Sunstruck. In a gigantic, pitch-black warehouse in a remote area of Melbourne’s Docklands huddled a ring of chairs. Two dancers moved around the space. A lofty golden light on a rail-track circled behind us, casting luminescence and shadow upon the pair. It was a sun; we watched a world. The shifting light made shadows dance, evoking planetary cycles, a human sundial or shifting continents. There was no context, no explanation, but this interpretive openness conjured up uncountable possibilities. The two performers presented a rich contrast, Trevor Patrick a brittle, pointed form to the earthy muscularity of Nick Sommerville.

After the many, often successful choreographic experiments of the 2008 MIAF, Sunstruck alone seemed to genuinely achieve that daggy, old-fashioned result so rarely sought these days—theatrical magic, and the sheer wonder of the living body.

–

Melbourne International Arts Festival: Desert Island Dances, devisor-performer Wendy Houstoun in collaboration with John Avery, music John Avery, lighting Nigel Edwards, Arts Centre, Oct 9-13; Chunky Move, Two Faced Bastard, direction, choreography Gideon Obarzanek, Lucy Guerin, performers Vincent Crowley, Antony Hamilton, Michelle Heaven, Stephanie Lake, Brian Lipson, Byron Perry, Lee Serle, design Ralph Myers, lighting Philip Lethlean, costumes Paula Levis, composer Darrin Verhagen, Arts House, Meat Market, Oct 8-12; Lucy Guerin Inc, Corridor, choreography Lucy Guerin, performers Sara Black, Antony Hamilton, Kirstie McCracken, Byron Perry, Harriet Ritchie, Lee Serle, sound design Haco, set design donald Holt, lighting Keith Tucker, costumes Paula Levis, Susie Gerraty, Arts House, Meat Market, Oct 16-25; Deborah Hay Dance Company, If I Sing to You, choreography, direction Deborah Hay, performers Michelle Boulé, Jeanine During, Catherine Legrand, Juliette Mapp, Chrysa Parkinson, Amelia Reeber, Malthouse, Oct 19-21, Sunstruck, by Helen Herbertson, Ben Cobham, director Helen Herbertson, performers Trevor Patrick, Nick Sommerville, design, lighting Bluebottle, Ben Cobham, set realisation Alan Robertson, soundscape Livia Ruzic, music Tamil Rogeon, Tim Blake. Shed 4, North Wharf Road, Docklands, Oct 13-18

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 2

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

PREMIERING AS PART OF THE MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL, JENNY KEMP’S LATEST WORK, KITTEN, DRAWS INSPIRATION FROM THE STORY OF ICARUS. THE WAX AND FEATHERS ARE GONE, REPLACED BY NEOPRENE AND MICROPHONES, AND KEMP’S FASCINATION LIES NOT WITH THE YOUTHFUL CURIOSITY OF ICARUS NOR WITH THE NATTY CRAFTSMANSHIP OF DAEDALUS, BUT WITH THE NARRATIVE DYNAMIC OF THE MYTH, ITS FREEFALLING VERTICALITY.

However, Kemp inverts the arc of Icarus and begins underwater. A woman, Kitten, realises her husband, Jonah, has somehow descended from the cliff outside their house and disappeared into the waters below. Her husband’s friend, Manfred, continues the archetypal nomenclature and acts as a well-worn third wheel. The ensuing action, narratively speaking, follows Kitten as she and the watchful Manfred search for Jonah but find each other—a romantic structure as old as L’Avventura. Like Antonioni, Kemp is not interested in the narrative suspense of the search, but on the other hand, neither is she interested in the relationships. The only driving force behind Kitten is the internal life of the eponymous character.

This life is refracted through the prism of Kitten’s triple casting. Margaret Mills and Natasha Herbert, regular collaborators with Kemp, as well as Kate Kendall, don’t play vastly different versions of the role, but their combined energies suggest the fracturing of Kitten’s mind. Beset by the trauma of Jonah’s disappearance, Kitten is plunging through her grief without rational anchor points—Manfred is a characterless vacuum, only capable of bankrolling Kitten’s increasingly tangential searching.

In the end, Kitten’s freefall takes her, and the audience, from the thick, submerged world of the first act, through the temperate naturalism of the second act into the stark, clinical clarity of a psychiatric ward. At this point, jumping into a liminal space of polar bears and inflated tuna, Kitten performs a concert. Kemp stays true to her inversion of the Icarian arc and finishes with this theatrical parachute, a floating denouement, where the audience leaves the theatre to find themselves in Crete.

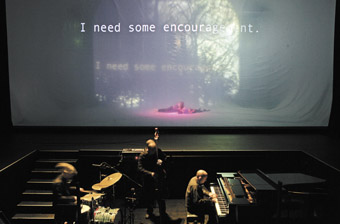

Back to Back with The Necks, Food Court

photo Jeff Busby

Back to Back with The Necks, Food Court

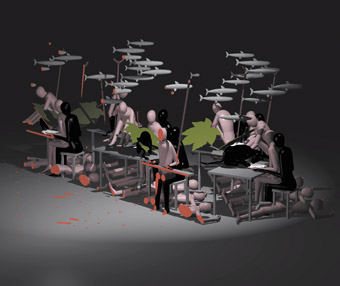

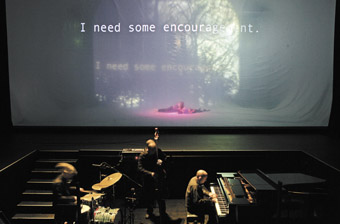

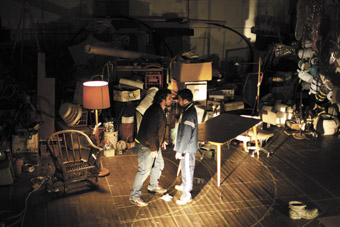

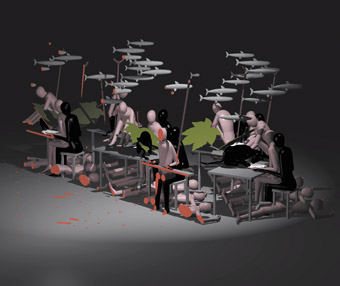

There are no parachutes in Back to Back’s Food Court. Bruce Gladwin and his team of co-creators have produced a formidably terrorising piece of theatre that also achieves astonishing beauty.

Back to Back is a remarkable company in itself, not least because it maintains a steady ensemble of actors. Throughout the company’s 21-year history, these actors, all with disabilities, have aimed at challenging audiences to reconsider their “unspoken imaginings.” Within this paradigm, the pieces that are created also serve to challenge and re-energise the performers—the ensemble’s welfare being integral. However, to regard the company’s work as primarily therapeutic denies the danger of the theatre that is produced and merely serves to reaffirm the binary of abled/disabled that is being deconstructed.

Food Court begins and ends with music. Led to the orchestra pit by torchlight, the inimitable trio of The Necks begin by building a slow trickle of sound in the dark—a cymbal scratch here, a solitary chord there. Their music has always created a sense of inevitability. Its driving pulse and dynamic is constantly building towards a climax that never quite arrives and a resolution that leaves no conclusions, simply space for silence.

In Food Court, The Necks meet their theatrical parallel. The action onstage opens in front of a curtain with a lone man placing a chair in the darkness. He then walks downstage, removes a white marker from the floor, and places it at the foot of the chair. A brilliant conceit—is the mark wrong, or is he? And in that question, in that moment, we are faced with our own judgment and perhaps taken aback by his confidence, his precision and his comedic sensibility. It is the first delicate, perfectly-pitched note.

Then, like figures from a Diane Arbus monograph, two women, clad in lurid gold leotards, take to the stage and begin an innocuous conversation. “Have you ever eaten a hamburger?” But with the arrival of a third woman at the other side of the stage, their attention and manner shift markedly. They begin to tease her about her intellect, her personal hygiene and her weight.

The barrage of abuse continues and becomes both abstracted and reified behind what appears to be a plastic scrim. In fact, it’s an inflatable cube of plastic that diffuses the shapes inside it while providing front and rear screens on which to project images and text. Beyond its practical attributes, the bubble acts like a Jungian ewer of the objective psyche—displaying a dreamlike state of archetypes engaged in sadism, torment, desire and struggle. Throughout this, The Necks drive on, carrying us through a forest of our own shadows.

Finally, our voiceless victim finds herself alone. It has taken 50 minutes for her to speak and, when she does, her voice cracks the air with a rush of forthrightness tinged with venom. She speaks the words of Shakespeare’s Caliban (“Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises…”) and, in so doing, throws off and embraces the weight and complexity of theatrical representation and history, leaving us both punctured and inspired.

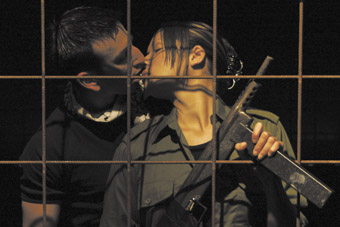

Shakespeare is given another rather different outing in OKT/Vilnius City Theatre’s accomplished production of Romeo and Juliet. The Lithuanian company is headed by the wry, floppy-haired Oskaras Korsunovas, who treats the text with élan—setting the action in rival bakeries and giving the story both the seriousness of social drama and the pep of bawdiness.

Korsunovas’ first gambit is a textless overture of competition, envy, sex and curiosity. The large cast immediately display their physical agility and alacrity, zipping from vignette to vignette across the steel bench tops. The set has both the whimsy and the darkly fantastical detailing of a Jeunet and Caro film and the posturing of the Montagues and Capulets is cleverly undermined by the mirror-image sameness of their respective kitchens. Korsunovas reveals that, for all their fear and loathing, their differences are merely imagined, yet this, in turn, renders them all the more tragic.

From this departure point, Romeo and Juliet steadily develops and expands. It captures the expressive youthfulness of its romance and matches it to the deep ferocity of its older generations. It also builds up a bank of imagery based on the vocabulary of the kitchen—ladles become weapons of masculine scorn, flour gives both life and death—that pulls the play back into the concrete world of social drama without in any way diminishing it. As it began, the production concludes wordlessly, but now, rather than hubristic poses, the tragedy is rendered by a silently aching collapse.

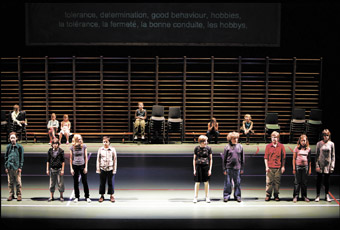

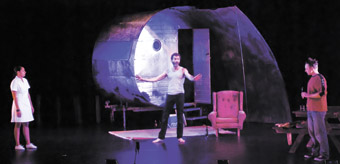

Victoria, That Night Follows Day

photo Phile Deprez

Victoria, That Night Follows Day

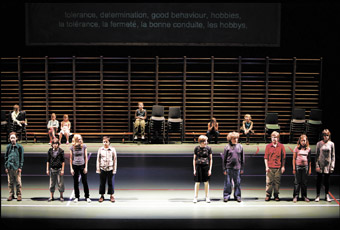

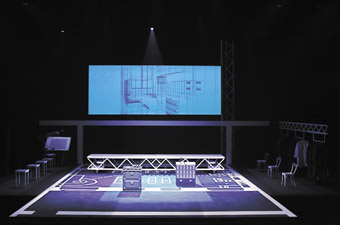

In Tim Etchells’ That Night Follows Day, there is no such poetic physical imagery. That is not to say that there is no poetry—the wonder of this production is in its essentialism. Working with the Belgian company Victoria, Etchells has crafted a brilliant provocation in a deceptively naïve guise.

The cast of sixteen children are a chorus of voices listing with mantric clarity the ways in which adults construct the cosmos around them—“You feed us. You dress us…You tell us to be quiet…You act surprised.” The children stand across a stage decked out in the features of a multi-purpose school hall. It is a beguiling and carefully created simulacrum—the chairs are the right size, the playground antics seem genuine, the screen for surtitles even has the powdery finish of a chalkboard, surely the clothes worn by the children are their own. Of course, the clothes are not their own, they are costumes, and the playground scene is choreographed, after all, this is theatre, this is artifice. But Etchells also knows that his audience of adults look to children not for artifice but for authenticity, for that elusive prelapsarian truth.In this respect, That Night Follows Day is as much a show about theatre as it is about the adult-child connection. Like Food Court, it engages the audience with an artifice that subtly subverts the traditional discursive structures of spectatorship—not by literally stamping on theatrical convention but by metaphorically returning the audience’s gaze. As a result, both pieces provoke questions, not answers and shift our perspectives rather than merely pleasing them.

Melbourne International Arts Festival: Malthouse, Kitten, writer, director Jenny Kemp, performers Chris Connelly, Natasha Herbert, Kate Kendall, Margaret Mills, designer Anna Tregloan, composer, sound designer Darrin Verhagen, lighting Niklas Pajanti, choreographer Helen Herbertson, Malthouse, Oct 8-25; Back to Back Theatre, Food Court, director, designer, devisor Bruce Gladwin, performer-devisors Mark Deans, Rita Halabarec, Nicki Holland, Sarah Mainwaring, Simon Laherty, Scott Price, Sonia Teuben, Brian Tilley, music The Necks, set design & construction Mark Cuthbertson, lighting design, technical direction Andrew Livingston, bluebottle, animated design Rhian Hinkley, sound design Hugh Covill, costumes Shio Otani, Malthouse, Merlyn Theatre, Oct 9-12; OKT/Vilnius City Theatre, Romeo and Juliet, writer William Shakespeare, director Oskaras Koršunovas, set design Jurate Paulekaite, Arts Centre, Playhouse, Oct 22-25; Tim Etchells and Victoria, That Night Follows Day, concept, text, direction Tim Etchells, design Richard Lowdon, lighting Nigel Edwards; Malthouse, Merlyn Theatre, Oct 22-25

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 3

© Carl Nilsson-Polias; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

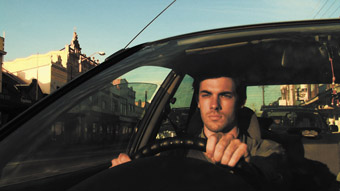

The Meaning of Moorabin is Open for Inspection

photo Michael Williams

The Meaning of Moorabin is Open for Inspection

ANY WORK OF ART IS A WORLD UNTO ITSELF; ONE THAT ALSO ATTEMPTS TO COMMUNICATE TO OTHERS ITS OWN IDIOSYNCRATIC CULTURE. IN RECENT TIMES THIS LINE OF COMMUNICATION HAS MOSTLY RESIDED WITHIN AN HIERARCHICAL FRAMEWORK. THAT IS, THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN PERFORMER AND AUDIENCE HAS OCCURRED AS A STRICT PROTOCOL BETWEEN THOSE BEING OBSERVED AND THOSE DOING THE OBSERVING. THREE RECENT WORKS AT THE MELBOURNE INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL AIMED TO CORRUPT THIS PROTOCOL. IRONIC, ECCENTRIC, AND AT TIMES QUIETLY DEVASTATING, THEY SET A FRESH BREEZE BLOWING THROUGH THE MELBOURNE PERFORMANCE SCENE.

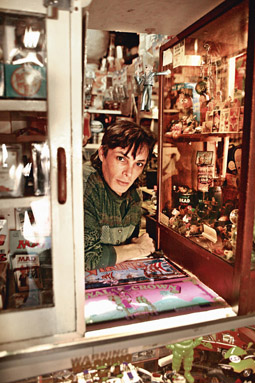

nyid: the meaning of moorabin…

I’m sitting in a freshly upholstered mini-bus with two punters from Perth when our driver Lydia loads a disc into the CD player. The gently mocking voice of concept creator David Pledger of NYID (Not Yet It’s Difficult) announces four less than salubrious Melbourne landmarks as we make our way to Moorabin, and invites us to consider our journey to this inconspicuous south eastern suburb alongside some classic Australian rock anthems. The Angels’ Doc Neeson rails against suburban oppression in the band’s rendition of “We gotta get out of this place” while Dave Warner from the Suburbs reminds us that he was indeed from the suburbs, in his cheeky pop mock tune “I’m just a suburban boy.” “Warner’s from Perth”, pipes up one of the punters from the most isolated city on the planet, while I’m successfully reminded of a boozy night spent in Moorabin’s South Side Six Hotel some 35 years earlier. Yes, the meaning of Moorabin is open for inspection, as we both begin to dissect memories from our respective lower middle-class pasts.

Arriving at a house that NYID Real Estate will eventually mock sell during a ‘public’ auction is at once novel and savage. Each room within this house, as well as spaces defined by the presence of wardrobes and bare mattresses in bedrooms, shirts and an ironing board in a sunroom, film projected upon a venetian blind in the lounge room and the obligatory incomplete white Holden panel van lurking in a masculine bound and sexually charged garage, have as their foundation text Gaston Bachelard’s 1958 seminal work The Poetics of Space. In search of inspiration, artists need look no further than the spaces contained within a domestic dwelling, and the labyrinth of the unconscious that these spaces of memory, mind and imagination inspire. With this work though, NYID have upped the ante. In 2008, a participatory culture is also one in which the commodification of intimate experience has become an explicit characteristic of artistic practice. Regardless of the quiet tragedy of a life lived in the suburbs, the meaning of Moorabin, like black gold, is now a marketable commodity and indeed, open for inspection.

“The successful bidder will receive a visual documentation of The Making of the Meaning of Moorabin including excerpts of selected video artworks and selected footage of interviews with potential buyers and associated research subjects which will have been uploaded onto the company’s project website during the presentation and viewing of the property. The successful bid will be donated to charity.” http://themeaningofmoorabbin.com.au

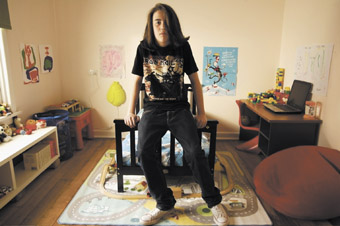

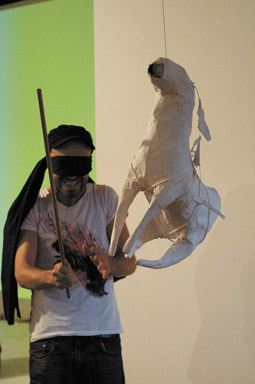

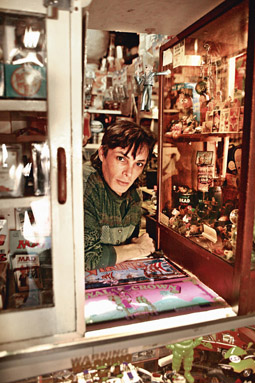

Panther, Exercises in Happiness

photo Alison Bennett

Panther, Exercises in Happiness

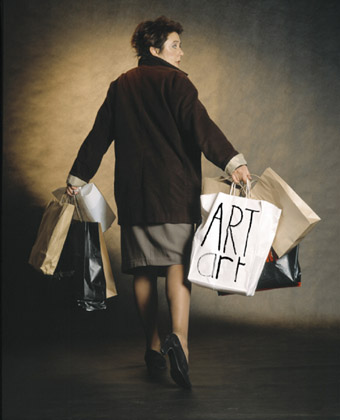

panther: exercises in happiness

Climbing a narrow stairwell to a first floor space situated above a tyre repair business, I’m immediately handed a scorecard. Co-creator Madeleine Hodge then fires off a series of questions meant to test my suitability for Exercises in Happiness. Yes, I live alone. No, I’m not involved in a permanent relationship… And on the questions go until, thoroughly qualified by an increasing sense of isolation, I go to the top of the class and am permitted to explore Panther’s eclectic environment.

As I investigate each exhibit and attempt to rate each on a happiness scale of 1-5, I become unhappy. If NYID commodified intimacy, Panther requires we assess subjective experience via techniques of market research. There’s “Things to do before I Die”, which induces a fine sense of melancholia, not because of a fear of annihilation, but because the majority of answers scrawled on a white wall in lead pencil avoid the question. Over by the north wall resides “The Garden Wilderness” comprising miniature human figurines placed within and alongside king-sized pot plants and other insurmountable and arbitrary greenery. Nature’s devastating indifference and our narcissistic inability to recognise this makes me sigh, then want to cry, and throw myself face down on the floor and die…But this is not to be; Panther’s other half, Sarah Rodigari, has other ideas.

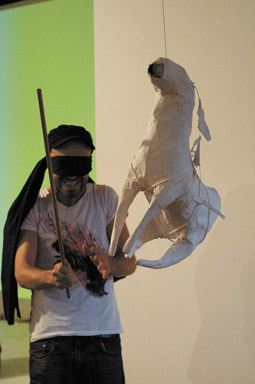

As if trying to sell me a vacuum cleaner, Rodigari corrals me toward the “Piñata Shot.” We share a hit of tequila amidst a mutual concern for the state of our speckled livers, then like some humiliated and blustering town idiot I’m blindfolded, given a big stick, spun three times in order to accentuate the rush of 30 proof alcohol to my pallid brain and prompted to strike a papier mache donkey that hangs somewhere in the turbulent darkness. By the end of it all I have acquired an exhilarating sense of despair. That fast fading idea of the recuperative power of art has been put through the mincer, and so have I. Forced to participate in an ironic dissection of my own pithy understanding of what art has become, I am bundled back down the stairs and out onto the street as a marketable commodity; fully researched and ready for my chosen demographic, all prepared to spread the word and commodify.

Joseph O’Farrell, Newsboys, Lone Twin & The Suitcase Royale

photo Tom Supple

Joseph O’Farrell, Newsboys, Lone Twin & The Suitcase Royale

lone twin & the suitcase royale: newsboys

This commodification of the individual achieved catharsis in Newsboys. A humble show, it nevertheless, in retrospect, provided the previous two with a progressive through-line that, all three combined, became a caustic comment on the state of the art during a global economic meltdown.

As a former paperboy myself, I was empathetic while watching members of The Suitcase Royale attempt to give away copies of a broadsheet titled The News during peak hour on Federation Square. Dressed like characters from Oliver Twist—floppy caps, grandpa shirts and knickerbockers—they were largely ignored by a crowd preoccupied with i-Pods and 3G mobile phones. Yet this intervention of an archaic form of communication into a culture largely unconcerned with its history was also a wry commentary upon the desperate status of the artist in the 21st century.

Selling newspapers was a performative act, as those of you who can remember the rhetorical rendition of a newspaper’s title—registered by pubescent vendors on city streets—as being a primal scream for commercial means. If you did not perform you did not sell, and many a paperboy succumbed to the fear that accompanied being forced to scream in public at peak hour. And so it is for the artist in the 21st century. Intervening in a cultural flow and criticising the conventions that govern our lives is an act of courage that often goes unnoticed. And so it was in Fed Square when I approached a member of The Suitcase Royale and requested a copy of The News. “Thanks mate”, he said, and his appreciation was heartfelt. Later, when reading the broadsheet, it became clear that its stories were private anecdotes of people interviewed for the project. One headline read: EVERYBODY’S OUT OF JAIL. Like The News, these performances by NYID, Panther and The Suitcase Royale that cast a critical eye over the commodification of the individual were free of charge, part of MIAF artistic director Kirsty Edmunds’ broad agenda to encourage audience participation in the festival. Freedom from the trite constraints of commodification is a necessary component of any participatory culture.

The Meaning of Moorabin is Open for Inspection, concept/creation David Pledger, project coordinator Lydia Teychenne, sound Lawrence Harvey, lighting Niklas Pajanti, website designer Alex Gibson, online Video Artist Jarrod Factor, photography Michael Williams, film editors Greg Ferris, Mark Atkins, Moorabin, Oct 9-25, http://themeaningofmoorabbin.com.au/; Exercises in Happiness, Panther & Tape Projects, creators Sarah Rodigari & Madeleine Hodge, Tape Space, Oct 11-25; Lone Twin & The Suitcase Royale, Newsboys, Federation Square, Oct 8-13, Melbourne International Arts Festival, October 9-25, www.melbournefestival.com.au

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 6

© Tony Reck; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jan Lauwers and Needcompany, The Deer House,

photo Maarten Vanden Abeele

Jan Lauwers and Needcompany, The Deer House,

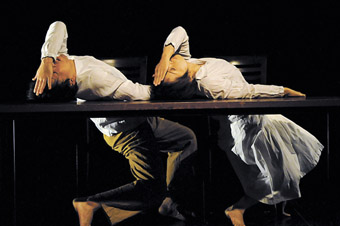

A MATRIARCH STANDS OVER HER DEAD DAUGHTER’S PALE, SUPINE BODY. SHE HAS AWKWARDLY DRESSED HER LONG-LIMBED ADULT-CHILD, WEEPING THROUGH HER FRUSTRATION, CHOKED BY MATERNAL PAIN BUT DETERMINED TO CONTINUE, TO REMAIN A CONSTANT THAT THE REST OF HER FAMILY CAN RELY ON. HER GRIEF-STRICKEN FACE IS FRAMED BY TWO OVERSIZED PIXIE EARS, HER BATWING-SLEEVES TRAIL FRINGES OF MOUSEY HAIR. BUT DESPITE THIS GNOMISH INCONGRUENCE, SHE COMMANDS RESPECT.

All eyes are drawn to her, a bold figure in the sparse white landscape of the stage. Beyond the platform where her daughter lies, on the outskirts of the colourless expanse, large rubber stags stand pallidly in line and the small ivory torsos of deer are heaped haphazardly under rows of huge antlers hanging on the far wall. Family members take their time at the corpse’s side, her long blonde hair falling over them onto the bare podium as they hold her.

The mother—the inimitable Viviane de Muynck—moves downstage towards us. No longer crying, her canorous voice is strong and unstrained as she addresses us directly. For now she is no longer the mother of the girl, but Viviane the performer, the storyteller recounting the back story to what we have just witnessed. She speaks about a Europe that has become a wilderness, and a family seeking refuge from the atrocities of war in an abandoned station, deep in the countryside. This is the deer house, a sanctuary from which they sell antlers to survive. As her musical words paint landscapes in the imagination, her round eyes settle on every one of us. Her gaze captures me and I could be sitting by a fire listening to fairytales. She is mother to all of us.

But something goes wrong. The mesmerising flow of her speech stalls and sputters. She’s lost her way, she struggles to finish a word, she can’t push it out of her mouth. Her eyes panic, glaze and fix on a distant spot. The family crowds in as she crumples. A jumble of languages rises from the bodies huddled round her. We crane to catch a glimpse of her, shocked into tenseness as the represented world invades its own narration.

For tonight we all seem to be part of this family, as Jan Lauwers and Needcompany tell us about community and death and the blurry boundaries between theatre and the world, where the real and the simulated merge and overlap, and intimate human conflicts are a microcosm of encompassing global occurrences. The performance centres on an actual event: the death of dancer Tijen Lawton’s brother, a war photographer killed in Kosovo while Lawton was on tour with the company.

At the start of the show we see the company’s dressing room reconstructed: the performers cavort around semi-naked, cheekily attention-seeking as they exchange jeans and tracksuits for rustic elfin tunics and large impish ears. Although playful, they’re equally absorbed in darker topics, stories of violence and death. They read extracts from a diary discovered by Lawton in Pristina when she identified her brother’s body, and from this a new story arises.

A war photographer is forced to choose between shooting a mother or her child to save the other. He kills the woman, and journeys with the body to the rural home of her relatives. They must decide whether he should die for his crime, and then whether his killer should also die. The Needcompany family assume the roles of this folkloric clan with a Brechtian-style self-awareness, presenting a narrative that dips in and out of its own frame, as the characters —and the corpses—step in and out of the action, attempting to alter or prevent the story’s progression.

The Deer House is the third part of Jan Lauwers and Needcompany’s Sad Face/Happy Face trilogy, following on from Isabella’s Room (2004) and The Lobster Shop (2006). While the first two parts focused on the past and the future, this third instalment looks to the present. And the company’s frenetic, unpredictable presentation aptly reflects its fleeting ephemerality. Dance, music, performance meld into a new, self-reflexive form, embedding skilfully manipulated reference to earlier mythologies, including the mourning rituals of Greek tragedy. The multilingual musician-performers also mix and match French, English and Dutch, the surtitles flashing as ideas fire simultaneously, tightly packing in ambiguous images to constantly widen the breadth of associations.

Jan Lauwers and Needcompany, The Deer House

photo Maarten Vanden Abeele

Jan Lauwers and Needcompany, The Deer House

The show careers ahead of us and moments we can’t catch are swept up in the commotion; sometimes it’s a struggle that fragments our concentration, but then we are reined back in, particularly when characters attempt to take control of their present, trying out alternative possibilities. Their stories are a way to stall death: perhaps this bag is full of stones instead of a child’s body; perhaps the photographer doesn’t have to die. But ‘no-one writes their own story’ and the present inexorably progresses, even though we can’t see how after such momentous and tragic events. Just as the matriarch picks herself up and carries on with the tale, life itself continues after bereavement. Routine and order are broken, but trepidation is eased away as a new structure is settled on. Stories rise from death, providing ways to continue.

So at the end of this epic journey, hope grows from despair. Perhaps, as the characters suggest, grief is “the only thing that keeps all cultures from falling to bits”, providing “the driving force for the new.” The performers sing out a final image of community in this fantastical, ridiculous world: “We are a small people with a big heart, we love each other and it’s a real art.” Spectres of the chorus from an ancient Greek tragedy, perhaps.

Jan Lauwers and Needcompany, The Deer House, text, direction, set design Jan Lauwers, music Hans Petter Dahl, Maarten Seghers (except “Song for The Deer House”, Jan Lauwers), performers Grace Ellen Barkey, Anneke Bonnema, Hans Petter Dahl, Viviane De Muynck, Misha Downey, Julien Faure, Yumiko Funaya, Benoît Gob, Tijen Lawton, Maarten Seghers, Inge Van Bruystegem, choreography the company, costumes Lot Lemm, lighting Ken Hioco, Koen Raes, sound design Dré Schneider; Kaaitheater, Brussels, Sept 25-27

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 8

© Eleanor Hadley Kershaw; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Erth, Nargun and the Stars

photo Heidrun Löhr

Erth, Nargun and the Stars

FERGUS LINEHAN COMPLETES HIS SYDNEY FESTIVAL DIRECTORSHIP WITH A MEATIER THAN USUAL PERFORMANCE PROGRAM, ONE POPULATED IN PARTICULAR WITH EPIC WORKS FROM FOUR TO NINE HOURS; A SLENDER DANCE LINE-UP (AFTER THE AUSTRALIAN RICHES OF 2008) ALBEIT WITH THE SUBSTANTIAL PRESENCE OF STAR UK CHOREOGRAPHER CHRISTOPHER WHEELDON (WORKING LARGELY OUT OF THE US); AND A CONTINUING PASSION FOR THE SERIOUS END OF THE POP MUSIC SPECTRUM. AS EVER WITH LINEHAN, SYDNEY ARTISTS OF ANY IDIOM ARE LUCKY TO GET A LOOK IN—ERTH VISUAL & PHYSICAL AND SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ARE THE FAVOURED TWO IN 2009. THERE’S ALSO A WELCOME FESTIVAL KIDS SEASON AT RIVERSIDE THEATRE, PARRAMATTA, THE HIGHLIGHT BOUND TO BE ERTH’S ADAPTATION OF NOVELIST PATRICIA WRIGHTSON’S NARGUN AND THE STARS. HERE’S MY FESTIVAL WISHLIST.

robert lepage: lipsynch

Marie-Anne Mancio wasn’t convinced that the 8 hour 35 minute work by Robert Lepage’s Ex Machina altogether cohered when she saw it at London’s Barbican Arts Centre (RT 87, p3), but along the way there was much to appreciate. She wrote, “In order to concentrate on the notion that voice is genetic (almost part of the fabric of the soul, whereas language or speech is encultured) Lepage courageously eschews the stunning visuals for which he is known. So, sets are witty and efficient—the side of a plane morphing into a train—but not spectacular. Instead, there is a glut of sound from singing to speeches, to a baby’s cries, to advertisements, to canned laughter. In a Los Angeles restaurant, conversation is punctuated with simultaneous translation and ringing telephones. Characters switch languages as do actors—text is in English, French, German, Spanish, Italian. On occasion, where surtitles are unclear, we are immersed in pure sound and sometimes, as [one character] tells us, music transcends failing language. As her son departs for California, [another] sings from Górecki’s Symphony no. 3 the lament in which the Virgin Mary asks Jesus dying on the cross to ‘Share your wounds with your mother.’ In other episodes we learn: we can speak without saying anything (President Bush is quoted); the content of speech—however plaintive or important—can be reduced to an analysis of harmonics and frequency; by recording permutations for British Rail announcements, you could read your own obituary. And death does not mean your body stops farting.

“To its immense credit, Lipsynch is often very funny, moving, insightful and never boring. It deserves multiple viewings to appreciate all of its references and nuances, the motifs of loss, of absent fathers, biblical characters, dualism; the incredible performers who take us on journeys as their multi-faceted roles age, change context or gain knowledge.”

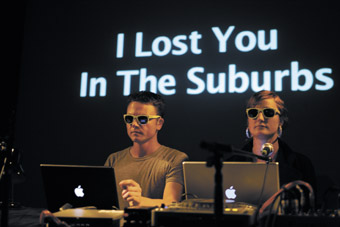

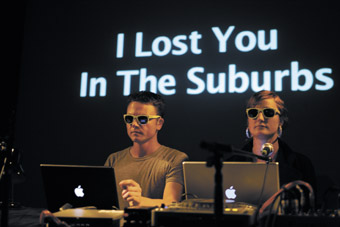

nature theater of oklahoma: no dice

Also focused on communication, this time around kinds of telling, is No Dice from New York’s Nature Theater of Oklahoma. Jana Perkovic in her review from Zagreb’s Eurokaz performance festival wrote, “Starting with traditional oral narrative as a model, No Dice is an epic, four-hour replication of hours of telephone conversations between group members (ranging from artistic laments to complaints about work, drinking and eating disorders, to ‘dinner theater’ experiences). It employs tropes of oral epic (repetition, variation) which clash with the tropes of Shakespearian theatre (acts, climaxes), which in turn clash with the overturned tropes of good acting (misplaced foreign accents, hyper-articulation, exaggerated costumes). Modes of communication split apart, nothing quite matching: even the gesticulation employed is their own confusing invention (including, but not limited to, the sign of the cross, thumbs up, mimed wall and some nameless but recognisable gestures, such as intravenous drug use). It is a legible, but closed system of references, until it suddenly opens towards the end: the actors take their wigs and sunglasses off and address the audience: ‘The question is, what do we require in order to enjoy ourselves?’ Communication itself, they conclude. Poignant, semiotically imaginative, intellectually provocative but emotionally rich, Nature Theater of Oklahoma’s performance—with its roundabout, illogical, confusing conversations—is a manifesto of faith in our ability to engage with each other through speech.” (RT86, p56). At only $25 a ticket (compared with Lip Synch’s $100-140), No Dice could be the festival bargain for the adventurous but cash-strapped performance-goer.

stc actors company: the war of the roses

Another welcome epic, The War of the Roses will allow us an extended glimpse (at eight hours) of rarely performed plays by William Shakespeare that offer a view of English history that is at once idiosyncratic and predictably Tudor. The cutting and pasting and editing of these sizeable plays (to make the playing time manageable and the history presumably comprehensible) is by Tom Wright (most recently Barrie Kosky’s collaborator on The Women of Troy) and the show’s director Benedict Andrews, who can always be relied on to create lateral but faithful and telling interpretations of classic works. The STC Actors Company, in their last outing, is joined by Cate Blanchett and Robert Menzies (Brutus in Andrews’ Julius Caesar) and the design is by Alice Babidge, who impressed with her set for The Women of Troy. The War of the Roses Part 1 includes Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V, Part 2: Henry VI, and Richard III. The rise and fall of kings and queens, their allies and enemies on fortune’s wheel, and of their own volition, right or wrong, is the grimly exhilarating stuff of the younger Shakespeare’s vision and will doubtless achieve additional topicality in the hands of Andrews and Wright.

morphoses/the wheeldon company

This is bound to be a fascinating program, not least because it’s the Australian premiere of Christopher Wheeldon’s own innovative company, such a rarity for a ballet choreographer these days, and includes the exacting Slingerland Pas de Deux (an excerpt from the truly surreal full-length postmodern ballet by William Forsthye, music by Gavin Bryars) alongside Wheeldon’s own creations, Fools’ Paradise, accompanied by a chamber orchestra, and his acclaimed Polyphonia, set to piano music by György Ligeti.

malthouse: the tell-tale heart

Barrie Kosky’s account of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart for Melbourne’s Malthouse with the virtuosic Martin Niedermair as the haunted murderer and director-adapter Kosky on piano (for songs by Bach, Purcell and Wolf) has induced trepidation and excitement wherever it’s been played around the world. John Bailey wrote, “This is a theatre of ellipses, in which the unsaid holds as much weight as the spoken word” (RT 82, p8).

katona józsef theatre: chekhov’s ivanov

Budapest’s Katona József Theatre and director Tamás Ascher set Chekhov’s early play Ivanov in the context of Hungarian rural culture after the Soviet Russian crushing of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising. If we see Chekhov’s plays as precursors, in a metaphoric rather than literal sense, of the Russian Revolution, then this version of Ivanov makes for an intriguing reversal of expectation. Here the focus is not “the fading Russian bourgeoisie” but is “planted…firmly within Hungary’s ascendant peasant classes of the 1960s.”

belarus free theatre: being harold pinter

Company B are hosting Belarus Free Theatre, an underground theatre project formed in 2005, and still banned, to battle the censorship imposed by dictatorial President Alexander Lukashenko. Being Harold Pinter draws on the playwright’s Nobel Prize acceptance speech and uses excerpts from his plays to reflect on life under dictatorship. In Belarus, the company continues to perform in homes and other unadvertised locations despite police harassment and job losses in a culture where theatres are otherwise state controlled. The Free Theatre’s performance style is reputedly raw and anarchic, winning praise for its performances in the UK. Sam Marlowe wrote in The Times (Feb 20), “Beneath a photograph of Pinter’s own watchful eyes, the cast of seven, dressed in grey suits…create a nightmarish kaleidoscope of darkness, light and blood-red. Their hands are stained as if by stigmata; their delivery is packed with punchy aggression, and the menace of Pinter’s writing becomes uncompromisingly overt.” Being Harold Pinter will also play at Q Theatre Penrith.

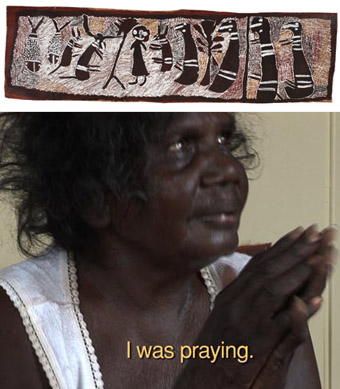

erth: the nargun and the star

s

A classic of literature for children here in Australia and the world over, Patricia Wrightson’s Nargun and the Stars (1973) was awarded the Australian Children’s Book of the year (1974) and the Hans Christian Andersen Medal (1986). When a boy’s parents are killed in a car crash, he is moved to a sheep farm to live with cousins he doesn’t know and there encounters and befriends mythical Indigenous creatures. But development in the area unleashes a vengeful spirit, the Nargun, in the form of a giant murderous rock. The boy must act, to save lives, but also the land. Adapted by playwright Verity Laughton and directed by Wesley Enoch and Erth’s Scott Wright, and blessed with Erth’s considerable skills at creature making and large scale puppeteering (like their baby dinosaurs for the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles), Nargun and the Stars should be a festival highlight for children and adults alike.

2009 Sydney Festival, Jan 10-31, www.sydneyfestival.org.au

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 10

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

La Fura dels Baus, SUB

photo Oskar Perez

La Fura dels Baus, SUB

LA FURA DELS BAUS IS KNOWN FOR ITS HIGHLY PHYSICAL AND CONFRONTING PERFORMANCE SPECTACLES. THE COMPANY HAS DEVELOPED ITS OWN THEATRICAL AND VERBAL LANGUAGE (FURAN), STYLE AND AESTHETICS. MY MEMORIES OF THEIR EARLIER WORK INCLUDE BEING CHASED AROUND BY MUSCLE BOUND MEN WIELDING CHAINSAWS, BEING PELTED WITH OFFAL AND HERDED AROUND BY GIGANTIC CARDBOARD BOXES.

La Fura’s work bursts out of the chaos of Barcelona. I discovered that nothing there is straightforward—not even finding out about their show, SUB. After a futile online investigation, I decided to leave it to fate. As I wandered down the back alleys of Barcelona, desperate to find some clue, I literally walked into the wall that bore the only extant poster anywhere in the city. And, as it happened, the last night of the performance was my last night in Spain.

The venue, Naumon, is an old Norwegian icebreaker ship that La Fura bought in 2003, saving it from being turned into scrap metal and returning it to life as a floating theatre on Barcelona’s harbour.

In SUB the line between theatre and life is blurred. The experience begins outside the boat, while the audience wait to board. Loudspeakers bark orders in a neat reversal of maritime law—women and children first! All the women talk and laugh nervously with each other—strangers bonded through fear and excitement at the mysteries awaiting us. One by one we proceed up the gangplank, leaving the men behind. Bags and bodies searched, we are pushed and shoved, forcefully herded down the dark stairs into the belly of the ship, a small torch our only source of light.

Down, down into the hold, like descending into hell. It’s dark and claustrophobic. We are forced to sit on the floor—bodies squeezed very closely together. Finally the men enter, with their energy and the stink of sweat, herded aggressively and made to sit opposite us. Doors shut, occasioning slight panic. It is now impossible to escape. We are all imprisoned—slaves or illegal refugees crammed into a freighter. Or into an Orwellian world in which people are powerless. And then La Fura dels Baus pull out all their party tricks—and it is one hell of a ride.

La Fura dels Baus, SUB

photo Oskar Perez

La Fura dels Baus, SUB

A performer drops through the ceiling hanging naked from a rope. Is he being punished for trying to escape? Are we all being punished? What is our crime? An amplified version of “Love Me Tender” booms from the opposite end of the boat. A woman, in boiler suit, sings karaoke as she descends the staircase, leading in the latecomers—the dispossessed. Her plea for love goes unheeded. Instead she is defiled, raped and hung from a meat hook. A powerless trophy of war?

Above us, two women and two men hurl paint, the drips forcing the audience to shift uneasily in the first of the company’s manipulative crowd/body orchestrations. Characters emerge from all directions—above, below, from the sides…Who is that big bellied man lurking in the shadows? A slave master ready to pounce? In a moment of pure theatrical release, the separated male and female audience members are allowed to reunite. In this subterranean domain there is panic to locate partners, wives, husbands, children—all of us forced to think about the ones in reality who will never find each other.

One side of the ship opens to reveal a ‘human aquarium.’ A man drops into the water, almost naked, a breathing apparatus in his mouth. The water turns red as another body plunges in. And another, and another, now without a line of air. The tank is getting overcrowded, limbs pressing against the scratched glass wall. At first they help each other breath, happily sharing their lifelines but friendship quickly dissolves into a watery struggle for oxygen and space. Outside the aquarium we are powerless—fated to watch but unable to help. And yet, how generous would we be in such a life and death situation? Would we share our last gasp of air with a stranger?

More airless moments: another two bodies are strung up—each totally covered in plastic, a snorkel their only source of air. But, instead of it bringing air into their plastic cocoon, air is being sucked out—the bodies become literally vacuum packed. The amplified wheeze of their breath echoes in this cavernous prison.

A booming voice-over infiltrates the space. A mythical tale unfolds, set in Queensland of all places, in which people are ordered to drink whatever they can find—but to purify it with a pill (a reference to the current debate over drinking recycled sewage). Following orders, a performer, suspended on the side of the boat, flops out his penis, relieves himself into a watering can, puts in a tube and then proceeds to drink this ‘precious’ liquid. Has he gone too far? Extreme circumstances cause extreme transgressions.

And, all throughout the performance, while bodies are dragged across the ground, suspended, vacuum-packed; or as we are chased by gigantic electric fans; while water gushes into the boat, is caught in buckets and thrown at the audience, or is sprayed at the performers; while they are finally strung up against a blank canvas only to be painted out of existence, there is the constant flash of mobile phones and cameras as members of the audience clamor to record the events. The horror preserved for later observation—once we are safely removed from the experience.

As I make my way through Barcelona’s streets, filled with the excitement of having been totally consumed by this performance, I reflect on how much I have been hankering for this style of extreme performance back home. On board the train, I sit in an airless carriage totally controlled by raucous hash-smoking Spanish teenagers. Is this part of the show? Have the lines between theatre and life totally disappeared?

La Fura dels Baus, SUB, text Ahmed Ghazali, Rafael Argullol, direction Younes Bachir, Carlos Padrissa, performers Samuel Delgado, Oumar Doumbouya, Irene Estrade, Zamira Pasceri, Younes Bachir, producer Isabelle Preuilh, coordination Adrìa Guadagnoli; venue Naumon, Barcelona, Sept 22-Oct 12, www.lafura.com

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 11

Brendan Ewing, The Red Shoes

photo Bohdan Warchomij

Brendan Ewing, The Red Shoes

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR MARCUS CANNING’S EXHIBITION CELEBRATING ARTRAGE’S 25TH ANNIVERSARY DEPICTED A FRINGE ORGANISATION DETERMINED NOT TO GROW UP AND TO REMAIN THE EDGY, EXPERIMENTAL—AND SOMETIMES HIT AND MISS—INSTITUTION OF ITS YOUTH. THE MESSY LIVE WIRE OF THE RETROSPECTIVE ASIDE, THE SUCCESS STORY OF THIS YEAR’S FESTIVAL WAS THE DANCE PROGRAM, ATTRACTING STRONG HOUSES AND REVIEWS.

Choreographer Bianca Martin presented her first large scale, full-length production, Home Alone, complete with an impressive if sparse two-storey set and onstage drummer, placing three dancers within an abstract world of troubled domesticity. Keira Mason-Hill—best known for her work with youth dance group Buzz—was the most happily playful of the performers, making one interlude where she was grabbed about the throat by an abusively dominating Joe Jurd all the more affective. In contrast Kathryn Puie’s aggressive athleticism combined with sliding grace saw her and Jurd clambering up walls and hanging from the steel-rimmed rafters in what occasionally looked like a homage to Fred Astaire’s famous ceiling dance in Royal Wedding (1951). Particularly in Mason-Hill’s dancing, there was a tendency towards ground movements and swinging body-twists in a low centre of gravity, contrasting with the up/down, climbing trajectories elsewhere apparent. A mime game of dinner involving cutlery and three cans of tinned goods traded amongst the performers appeared several times, imparting a sense of rhythmic continuity and return. Generally though, the piece was dramaturgically opaque, and the drummer was not used as often as one might have expected, with recorded music more frequently employed.

Compared with Paradise City and other athletic, post-Pina Bausch dance-theatre works seen in Perth in recent years, Martin’s Home Alone did not quite reach the right level of chaos, power, or density of relationships to fully soar. After Home Alone’s abuse scene, Puie retired to the upper level to crouch into herself and push about an old and out-of-place fake Christmas tree, suggesting a spirit in the attic whose physicality reflected through a glass darkly the actions of her fellows. With more attention to making visible such abstract relationships between the performers, Home Alone could make a fine contender for a Mobile States touring program.

Maho Sumiji, Shuichi Abiru, Selenographica

photo Christophe Canatpo

Maho Sumiji, Shuichi Abiru, Selenographica

Dyuetto presented choreography by locals Sete Tele and Rachel Ogle alongside Japanese duo Selenographica (Maho Sumiji and Shuichi Abiru), together with a less effective, schlocky socio-sexual critique from Melbourne’s Luke George. In recent years, Tele and Ogle have been working with the differently-abled company The Get Downers (RT87, p18). Not having observed the pair perform such technical material in their own work before, what struck me about N_TN_GLD was the physical difference and dialogue present throughout every aspect of their actions. Tele is black, weighty and masculine, Ogle white, female and long-limbed. The production generated a wonderful slipping and sliding of affect and stylistics across the pair, from moments when similar inflections, poses and ways of holding the criss-crossing bodily forms of the two seemed to meld them into a construct of very similar modalities, to other instances where Ogle’s lengthy extension of form or Tele’s meteoric redirection of inertia and mass carved two almost irreconcilable forms onstage.

Rachel Ogle, Dyuetto

photo Christophe Canato

Rachel Ogle, Dyuetto

The spatial dramaturgy and lighting reinforced the structure of the piece around this dialogue of separation and confluence. Tele started alone, in blackness, spot-lit from above, vibrating and articulating in a manner which erased his awareness of anything outside of the body and its neuroanatomical sensations. Here the performance recalled butoh. Then in a duet the dancers’ focus was still deeply internal, suggesting something of the non-human or posthuman in these bodies. N_TN_GLD ended with Ogle alone, hair masking her visage, and a sense of deep weariness and resistance to further action evident in her arms, her hands and the sometimes clawed shapes that decorated the space about her intermittently jerking, yet elegant columnar form.

French reviewers have focused on the exotic orientalism of Selenographica. What Follows The Act certainly could be read in culturally specific terms. The central role of critiques of the alienated husband-and-wife team in modern, post-WWII Japanese society and the arts after Mishima, butoh and Suzuki, does inform What Follows The Act. Selenographica however had none of the deliberate attempt to shock or to invoke taboos which was such a feature of this earlier work, reflecting a different trend in Japanese performance which has become more prominent since the 1990s, characterised by a deadpan, potentially comic lightness of touch. This is a mild, charming work, focusing on semi-improvised play and games between Sumiji and Abiru who begin by exploring how many movements and dialogues can be sketched between the pair as they sit, somewhat anxiously, at a domestic table, or later move towards and climb a prominently displayed ladder (a sign of escape perhaps?). To read such allusions in national terms would overstate matters. It is not just the Japanese who admire minimalism or enjoy quirky moments within an otherwise seriously performed work. In one particularly rich moment, Sumiji reclined on the table to let one hand snake and coil filigrees in the air, a totally pointless act whose joyful affectivity lies precisely in its unnecessary character. Such motifs place Selenographica at least as close to Euro-American dance theatre as to the particularities of Japanese aesthetics within today’s world of globalised performance—something which this company seems to embrace.

Outside of the world of dance, Mar Bucknell presented A History Of Glass. Better known for his more extreme performance art works, Bucknell’s Glass was a surprisingly gentle piece consisting of a soporific set of prose-poems describing a population caught within a room of glass, blasted by light from outside, and within which the boundaries, meaning and structure of everything become evermore hazy. Bucknell’s recitation was accompanied by an electronic soundscape whose organ tones evoked film-maker John Carpenter’s music, while Stuart Reid used a digital sketch pad to project a yellow tinted doodle which he constantly added to, its curling scratches and deep, inky outlines lending a third rhythmic element to this gradual unfolding of sound, text and image, filling the space and the time of the performance. Overall the piece had a durational quality, the experience of its slow length being a key part of its structure and affect. Bucknell’s prose could have used a firmer structure—several apparent climaxes arose in which the inhabitants suddenly became free to walk beyond the glass and across the yellow sands, before returning to their prison—but this also helped give a sense of repetitive sustain and detailing, which made for an enjoyably somnambulistic yet existentially dystopian work; shades of Sartre’s No Exit, to be sure.

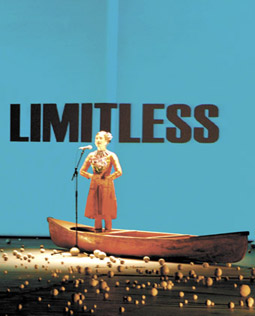

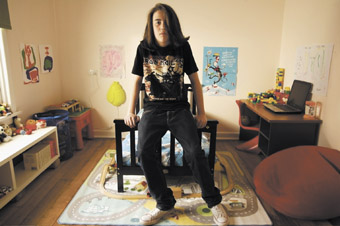

A festival highlight was director Matthew Lutton’s return from Sydney and Melbourne to stage Humphrey Bower’s adaptation of the Hans Christian Andersen story, The Red Shoes. Lutton’s most mature work so far, the production had a sparse, Grand Guignol nastiness to it. Paris’ infamous horror theatre of the early 20th century, the Grand Guignol employed a taut, dramaturgical understatement before releasing a fervid, melodramatic excess and buckets of blood. It was a theatre of shock, a style of performance structured more around scenographic electrocutions and tensed release than any coherence of narrative or character. Staged on a blindingly white stage, complete with trapdoors into which objects could be dropped and a piano centrestage behind which material was hidden, The Red Shoes positively blazed with red when the perverse young male protagonist Kevin (Brendan Ewing, also showing a level of craft over and above previous achievements) finally asked the woodsman to sever from his feet the glistening, imprisoning devil shoes which had overtaken him and forced him to dance, Tourette-like, forever.

George Shvetsov, his lanky form often casting gargantuan shadows above and behind him, was an equally sexually troubling presence, not a perverse character per se but certainly one capable of seducing all on stage (and in the audience) as they trembled before him. Igor Sas however virtually stole the show as a cross-dressing temptress (the Ice Princess) and Kevin’s stern, comically Catholic conscience (Auntie C). Explosions in intensity within this otherwise minimal structure were heightened by Ash Gibson Greig’s score, varying from eruptive noise to almost Weiner cabaret.

The Red Shoes could have gained clarity from dramaturgical development—quite what, for instance, was signified by having Kevin’s mother, the Princess, Auntie C and other female characters collapsed into the dangerously sexy form of Sas was unclear—but as indicated, horror is not necessarily a form which requires transparency of meaning. This was a theatre of effects, and such scenes as where the naked Ewing quaked in a veritable seizure of pain and desire as dark red liquid dripped across his white skin was sufficient to bind The Red Shoes into a richly affective, sadomasochistic pleasure.

2008 Silver Artrage 25th Anniversary Festival, curators Marcus Canning, Andrew Gaynor: Company Upstairs, Home Alone (The Suburbs Dream Tonight), choreography Bianca Martin, performers Kathryn Puie, Keira Mason-Hill, Joe Jurd, design Jamie Macchiusi, drums Tim Bates, lighting Deidre Math, Rechabites, Oct 30–Nov 8; Thin Ice Productions, The Red Shoes, text/adaptation Humphrey Bower (after Hans Christian Andersen), director Matthew Lutton, performers Brendan Ewing, George Shvetsov, Igor Sas, designer Claude Marcos, music Ash Gibson Greig, sound Kingsley Reeve, lighting Matthew Marshall, PICA, Oct 18–28; Bright Edge, History Of Glass, text/recitation/digital-slides Mar Bucknell, sound Allan Boyd, projected live drawing Stuart Reid, Blue Room, Oct 29-Nov 8; Strut, Dyuetto, N_TN_GLD, performer-devisors Rachel Ogle, Sete Tele, lighting Mike Nanning; Selenographica, What Follows The Act & It Might Be Sunny Tomorrow, direction, choreography, performers Maho Sumiji, Shuichi Abiru, direction, design Genta Iwamura, music Koichi Sakota, PICA, Nov 5-8, Artrage, Perth, Oct 17–Nov 23

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 12

© Jonathan Marshall; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Martyn Coutts, Willoh S Weiland, Deadpan

photo Bohdan Warchomij

Martyn Coutts, Willoh S Weiland, Deadpan

IN THE OPENING PANEL DISCUSSION OF THIS IS THE TIME…THIS IS THE RECORD OF THE TIME, A TWO-DAY SYMPOSIUM ON INTERDISCIPLINARY PERFORMANCE PRACTICE AT THE PERTH INSTITUTE OF CONTEMPORARY ARTS, JULIE VULCAN REMARKED OF UNREASONABLE ADULTS’ GIFT/BACK (2006) PERFORMANCE PROJECT THAT “YOU OFTEN DO NOT KNOW WHAT YOU HAVE BEEN GIVEN TILL FURTHER DOWN THE TRACK.”

With its wordy titular focus on the here-and-now, titt…titrott was staged to mark the 10-year anniversary of pvi collective establishing their practice in Perth, and situated deeper within the retrospective context of the Artrage festival’s Silver anniversary program. That both of these auspicious events took place at all, would seem like acts of defiance against the city’s natural-born tendency to efface local cultural memory and to continually replace and renew. Silver, a compelling historical exhibition of visual art and artefacts connected to Artrage over 25 years—installed throughout the vast spaces of PICA—celebrated the work of local practitioners both past and present and also served as a reminder, to me, of the more recent demise of the artist-run initiative in this my former hometown.

But while the mineral boom and rising real-estate values have pushed out artist-run spaces from the city, organisations like Artrage has shifted focus to devising programs that assist artists with longer-term development of new work. They have maintained ongoing relationships with practitioners—Artrage presented pvi collective’s first performance project, Easy Listening Under the Truth Serum, in 1998 and has continued to support the efforts of the collective ever since. Perth is also the site of two significant and collegiate national centres for research in emergent and cross-disciplinary art forms: SymbioticA, now a Centre of Excellence in Biological Arts at the University of Western Australia, and the pvi collective’s newly established Centre for Interdisciplinary Arts (CIA), both of which provide opportunities for residency, exchange and discourse with peers nationally and internationally. SymbioticA were hosting a visit by Steve Kurtz of the USA-based Critical Art Ensemble (CAE), who had been cleared in June of all criminal charges brought against him and another scientist in 2004 for procuring harmless bacteria cultures for an exhibition. It was around Kurtz’s lecture at UWA entitled Crossing the Line—a convergence of politics, activism, democracy, terrorism, freedom of expression, citizenship and justice—that the participants gathered, setting the tone somewhat for the symposium and performances to follow.

The event drew artists together from across the country including panther (Melbourne), Spat ‘n’ Loogie (Sydney), David Williams of version 1.0 (Sydney), Sam Fox of Hydra Poesis (Perth), Unreasonable Adults (Sydney/Adelaide), Deadpan (Melbourne), Something In Common [sic] (Perth) as well as producers Cat Jones from Electrofringe (Newcastle), Rebecca Conroy from Performance Space (Sydney) and Jeff Khan of the Next Wave Festival (Melbourne)—many of whom initially worked with pvi on their TTS Australia and Reform tours. Pvi collective divided the symposium event into two parts: this is the time…, an evening of performances held at The Bakery, and this is the record of the time, a two day symposium which book-ended the performance night. This is the time… provided an occasion for the participants and audience to reflect on a vignetted representation of an artist’s/group’s practice before returning to articulation and discussion around the realisation of their work. As such, punters arriving at this is the time… as a separately-billed event, expecting pvi to deliver on the promotional hyperbole of an evening that “promises to rattle the cage of contemporary performance practice as we know it”, might have been confused by the lecture-style delivery and necessarily pared-back nature of some of the works.

Something In Common (sic)

photo Bohdan Warchomij

Something In Common (sic)

One of the main topics of discussion throughout the symposium was the site-based or non-institutional nature of much of the work being produced by interdisciplinary performance practitioners in Australia today, and of the risks, challenges and possibilities of creating work on the “hybrid stage of public space” (a useful description offered by Andrew Donovan of the Australia Council’s Inter-Arts Office), collapsing the distance between art and everyday life while finding, engaging, implicating and including new audiences in performance experiences. The cabaret and installation format of this is the time… while somewhat paradoxical to the methodologies of most of the artists involved (Michelle Outram’s political oratory and endurance-based performance Not The Sound Bite!, for instance, originally conceived for Speaker’s Corner in The Domain in Sydney had an obviously decontextualised resonance when re-staged in The Bakery’s courtyard) afforded a semblance of projects past, present and in-development that all hinged around particular contingencies, whether political, societal, temporal, technological or environmental.

The scheduled part of the evening of live art, this is the time… began with Unreasonable Adults’ If Not For You Then Who with Jason Sweeney performing live and Fiona Sprott emerging from the white-noise-ether of videotape to deliver dark and self-annihilating monologues on sex, failure and illness. As a part of their collaboration, Unreasonable Adults are adaptable and deliberately flexible to the specificity of the moment in which a work is being made, choosing to deliver performance and other outcomes across the internet, through installation, videos and performance. For this event Sweeney punctuated the meditative slowness of the grainy black and white video and audio environment after each of Sprott’s confessions by writing in loud staccato on an amplified blackboard in chalk, questions like “ARE YOU DEAD INSIDE?”, renting apart the darkly comic reverie created in these scenes by questioning the emotional health of the audience.

Among the participants in the symposium Sam Fox of Hydra Poesis identified a personal intent to create a platform for outrage, pathos and emotion to be directed at perceived injustices as an honest form of communication back to the ”hegemony”, reflecting more violently comments by Michelle Outram during the symposium that artists should be “agents within their own culture” and by David Williams of the desire to “perform citizenship.” For this is the time…Hydra Poesis created a one-on-one interactive performance utilising a threatening teleprompter with the intention of causing the sole participant to feel fear or aggression. Meanwhile, panther, an artistic duo also interested in person-to-person relationships, arrived in Perth fresh from presenting their new work Exercises in Happiness for the Melbourne International Arts Festival [p6] wherein audience members could perform and articulate the things that made them happy, or occasionally find deep-seated sorrow as a result of being rejected from an experience of the work. For this is the time… panther also yelled at the stars in a proclamation that mixed nihilism with optimism, pessimism with passivity and gave philosophical answers to pragmatic questions (and vice versa).

On the first panel David Williams of version 1.0 responded to questions regarding the sustainability of an issues-based theatre and the actual time it takes to bring new work to the stage. Williams counterpointed the rapid delivery of much of version 1.0’s verbatim source material—Hansard, the transcript of parliamentary proceedings being complete and available on the day after a sitting of the Senate or House of Representatives—against the need for continual revision of a script in order for its issues to remain pertinent both to the company and to an audience cognisant of changing world affairs. Embellishing the history of version 1.0 in a performance lecture for this is the time… Williams also alluded to the inadequacy of critical language in providing feedback to new and developing forms of performance by quoting from the retinue of version 1.0 reviews, “Apparently we were ‘challenging and hilarious.’ Apparently we didn’t ‘have strong characters’ and, as such, ‘had no clear character motivations’.”

Cat Jones, a performer and a curator of Electrofringe also manipulated language through the relatively new form and sonic intonation of avatar dialogue through a ‘play reading’ of a cat_gURL interactive event. Delivering a verbal introduction to the experience of entering a previous installation, Jones intercut video documentation and her reading with live performances of webmistress cat_gURL’s automated, gendered script about sexing and finding definitive sexuality. Creating another kind of visceral/virtual paradigm that connected the fleshy with the flat and pre-recorded, Spat ‘n’ Loogie’s Holiday took members of the this is the time… audience away on a sensorial approximation of an exotic holiday, replete with cocktails, a walk in the sand and a mushy holiday romance.

In closing this is the time…this is the record of the time, a producer’s panel convened to discuss the ways in which certain organisations including Next Wave, Electrofringe and Peformance Space are continuing to support the development phases of interdisciplinary performance practice through programs such as Kick Start and by working in concert with one another. With the understanding that the field is continually redefined, reframed and revised by both practitioners and the changing nature of the social and political spheres in which they choose to make work, this is the time…this is the record of the time, was an invitation to participate in the nurturing of an artist-led commitment to hybrid performance practice. And it took place in Perth. While this was the place and a particular moment, the effects and the influences of the program will continue to be felt “further down the track.”

this is the time…this is the record of the time conference presented by pvi collective in partnership with PICA and Artrage, PICA, Oct 31, Nov 1; performances: The Artrage Bakery Complex, Oct 31

RealTime issue #88 Dec-Jan 2008 pg. 13

© Bec Dean; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jane Burton, Wormwood I (2006-7)

Courtesy of the artist and Bett Gallery, Hobart; Heiser Gallery, Brisbane; Johnston Gallery, Perth; Karen Woodbury Gallery,

Jane Burton, Wormwood I (2006-7)

FOR HALF THE YEAR TOKYO IS ONLY ONE HOUR BEHIND SYDNEY—SO CLOSE YOU CAN CONDUCT NORMAL BUSINESS ACTIVITIES AND MAINTAIN RELATIONATIONSHIPS AS IF YOU WERE JUST IN ANOTHER PART OF AUSTRALIA. MELATONIN LEVELS ARE RELATIVELY UNMODIFIED WHILE SENSES AND SOUL ARE OVERWHELMED BY OTHERNESS. PERHAPS THIS IS WHAT MAKES TOKYO FEEL NOT SO MUCH LIKE A FOREIGN COUNTRY BUT MORE LIKE A PARALLEL UNIVERSE.

trace elements

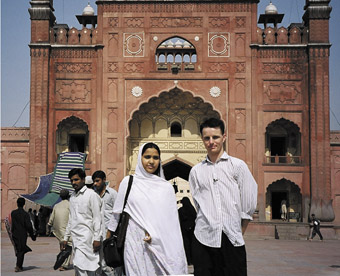

I was in this parallel universe for seven weeks undertaking a residency at Tokyo Wonder Site Aoyoama. Co-initiated by Artspace, Sydney the residency culminated in a group exhibition, Diorama of a City: Between Site and Space with fellow Australian artists Alex Gawronski and Tim Silver and Japanese artists Hiraku Suzuki, Exonemo and Paramodel. Co-incidentally another Australian/Japanese collaborative exhibition had just opened at Tokyo Opera City—Trace Elements: spirit and memory in Japanese and Australian photomedia—curated by Bec Dean from Performance Space with Shihoko Iida.

As with most activities I undertook in Japan, I got the instructions slightly wrong and entered the exhibition via the exit. This meant that the eroto-gothic photo manipulations, Wormwood (2005-07) by Jane Burton (Australia), were my introduction—sensual curves of female bodies caressed by shadows and forest branches. Burton’s images are richly evocative of adult fairy tales, perhaps a little undercut by the sterile corridor in which they are hung. However the resonance with Lovers (1994) by Teiji Furuhashi (Japan) in the next room installation serves as the correction.

As the video artist for Dumb Type it’s not surprising that Furuhashi’s is quite a performative installation. Images of naked people walk slowly around the four walls, meeting, embracing, passing through and by each other. Slide projectors on turntables rotate around the large room casting scanning lines across the images, while ceiling-rigged projectors throw messages onto the floor: “do not cross the line…” Melancholic chimes ring out, setting the meditative pace of the work that is all activity but with curiously little action. Its overly fussy mechanics reveal this is an early example of an immersive ‘multimedia’ environment.

Mixing with Furuhashi’s chimes are the clamouous explorations of Philip Brophy’s Evaporated Music (Part 1 A-F [2002-04, Aus]), in which the artist has remade the soundtracks to a series of popular music video-clips. Treating myself to the comfortable armchair I experienced the horror show that Brophy has made of Celine Dion’s ‘It’s all coming back to me now.’ The diva croaks through her lyrics, in desperate need of an exorcist, accompanied by wild foley and swirling 5.1 spatialisation. Infinitely more interesting than the original clip, full of film soundscape theory experiments, Brophy’s work provided a spikey element within the generally contemplative exhibition.

Continuing my backwards journey I worked from end to beginning across Japanese expatriate Seiichi Furuya’s series of images of his wife Christine. This course allowed me a little more ambiguity, and sense of discovery, in what is essentially a linear pictorial essay of love and loss. Accompanied by a booklet of excerpts from both Furuya’s and his subject’s diaries, the photos are mostly snapshots, personal moments, forming a deeply moving document of love and the tragic decline of a woman into irrevocable despair. Furuya has also made several publications, rearranging and regrouping the images to make sense of the course of events. Learning this later in the bookshop, I find the artist’s obsessive remembering even more tragic.