Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

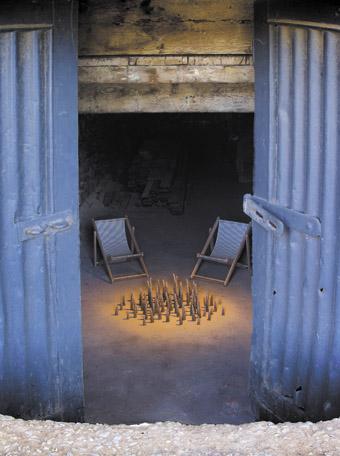

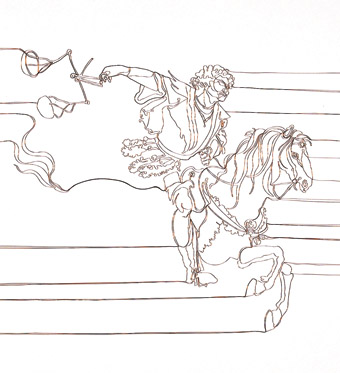

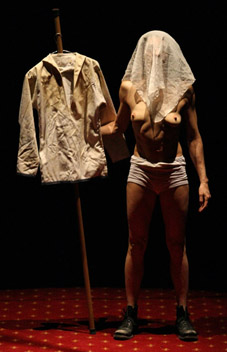

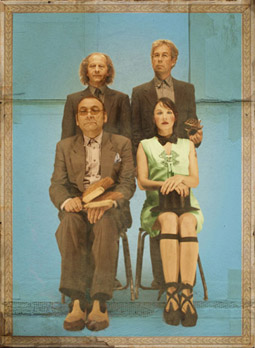

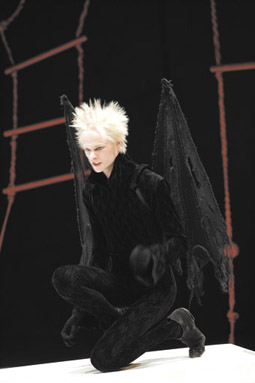

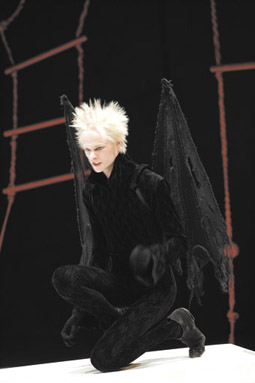

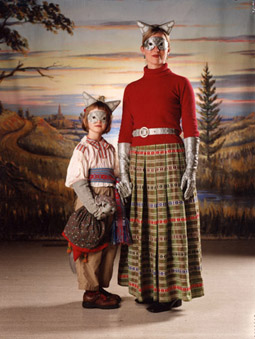

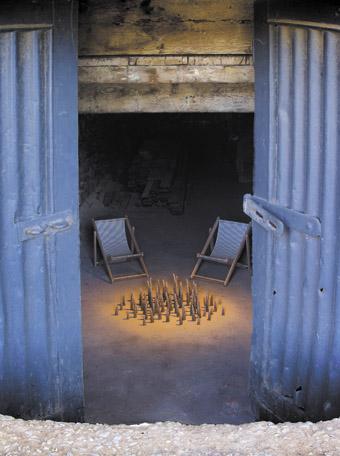

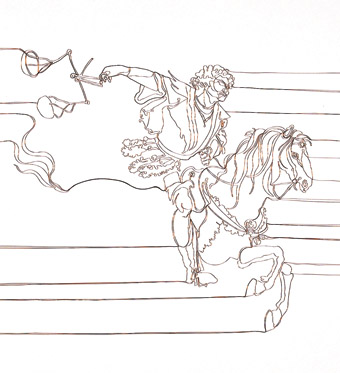

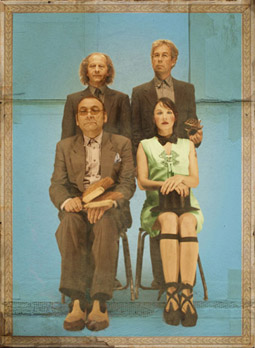

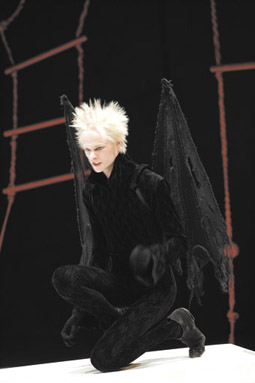

Guy Benfield, Maximum Commune (Ugly Business… on the basis of disbelief.), performance still

photo Jennifer Leahy, Silversalt, courtesy of the artist

Guy Benfield, Maximum Commune (Ugly Business… on the basis of disbelief.), performance still

IN AFTERMATH, BLAIR FRENCH, DIRECTOR AT ARTSPACE AND CURATOR, BROUGHT TOGETHER A GROUP OF ARTISTS ALL OF WHOM MANIFEST THEIR INSTALLATIONS THROUGH AN EXPLORATION OF PERFORMANCE, THAT IS, THE WORKS RESULT FROM A LIVE TRANSACTION BETWEEN ARTIST AND AUDIENCE. THE IDEA BEHIND AFTERMATH SEEMS TO BE TO EXPLORE THE ESSENTIAL PERFORMATIVITY OF INSTALLATION.

This is not in itself a new idea. French began to explore this notion in detail at Performance Space some years ago while working as its director in charge of time-based art. There, in influential projects like Cerebellum in 2002 with Gary Carsley, artists such as the Kingpins and Monica Tichacek presented video work alongside an exhibition of the ‘part objects’ of Leigh Bowery: his fake lips and costumes. In this show the images and videos were all part objects in that they could represent the whole absent object (Bowery or the other artists and their actions). In other words the objects and the videos were displayed only partly as things in themselves and mainly in terms of how they translated a performance event which was no longer comprehensible in any other way.

The blurb for Aftermath on the Artspace website indicates a similar focus on “the complex relationship of performance to installation art, sharing a genealogy, as they do, in early conceptual and post-object art.” But with Aftermath the emphasis is slightly altered as it “centres on the installation ‘aftermath’ of performance, or conversely, performance as a strategy for creation of material environments.” So rather than the installation being framed as the part object split off from the body of the artist, it now functions mainly as an object in its own right but one which represents “the bleeding back and forth of active models of performance and its post-life.”

guy benfield

Guy Benfield’s performance in Maximum Commune (Ugly Business…on the basis of disbelief) was designed to “re-animate tropes that were once declared obsolete, such as ritual, live action painting…the ‘Art informal’ movement in France, and the Japanese actionist painting movement-Gutai group.” And one should add the anarchic Paul McCarthy’s 1995 work Painter to this list as the most obvious intertext. Like all the artist statements in Aftermath, Benfield’s own descriptions of the work are worth examining for their oddly accurate account of the achievement of their experiments. He describes his essentially citational actions as “droppings” or “situational episodes” in a way that nicely combines the excremental notion of the art object as by-product of an ongoing process with the idea that the foundation of the performance action is its occurrence in space, its situated-ness, the aftermath of which is the installation.

The chaotic deconstructed pavilion motif of this work remained in the gallery for three weeks after the initial performance with a monitor displaying edits of the frenzied video documentation by TV Moore. The humour and energy of this piece reminded me of Benfield’s French Pup/live action (2001) a video work in which a long-haired rock guitarist dips the head of his guitar in paint and smears the walls and a canvas with it. Like Maximum Commune this earlier work is another play on performance and its various afterlives in recordings and documentations. The colour and chaos of the opening action was still in evidence three weeks after the event itself which is already I think the kind of effect the curator was after.

Ann Graham, Aftermath

photo Tony Bond

Ann Graham, Aftermath

anne graham

Anne Graham’s In Between Spaces comprised eight adjacent booths designed to correspond “to a normal dwelling: a bedroom, a bathroom, a kitchen, a studio, a library, a living room, an office and a gallery.” The initial performance (“situational episode”) involved a number of those present (yes me too) blowing up pink balloons for the “rumpus room” while Graham’s partner Tony Bond performed his signature risotto creation to feed all those in attendance. Their performative hospitality was no less sincere for its scale and constructedness. Perhaps this was evidence of what the blurb laid out as “the formal framework for the work” in a number of the “everyday routines that occur while occupying these spaces” in which the spaces become more than simply functional and approach the status of “social sculptures.”

The rooms/spaces were certainly organised and arranged after different activities with a DJ in one room, and hair cutting gear in another. But for me the room with the bars of soap and little carafes of urine was the most suggestive of the “intimate and familiar activities that…will appear strange due to their displacement.” (see RT80, p12).The repeated references in the artist’s statement to the dislocation of “normal” activities and arrangements is reinforced by the origin of these furnishings. The dark wood panels of the booths had been part of an old psychiatric institution and the artist had retained them for precisely this kind of work.

I don’t know if this installation can be described as “social sculpture” which operates on a broader and much more ambitious scale than this. But the sense of invitation to revisit was strong. The poeticised space of the different rooms was not so much a trace of an absent performance but a trigger for multiple interactions and experiences.

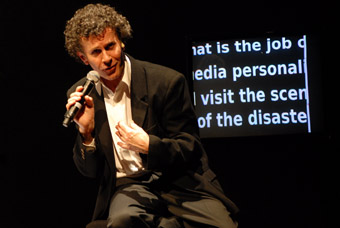

franz ehmann

“The new message reverberates in a never-ending forever young. I am with you, for you and amongst you.” I have no idea what the title of Franz Ehmann’s delightful work, forever young, references (please tell me it’s not the Alphaville track from their 1984 album) and his description of it as “a sculptural text food performance event with materials akin to theatre props” may not help those of you who didn’t see it (the polenta and mushrooms he made us on the opening night were delicious). His goofy and self-deprecating way of demonstrating the various interactive components of his installation was less about providing information and more about generating a sense of play so perhaps the title can be understood in terms of this childlike playfulness in the midst of endless reporting of violence and brutality.

Ehmann’s ‘newspaper floor’ was surprisingly sturdy and contained folds and tucks which could be used as spaces for the visitors to inhabit in various ways. Helpful instructions were provided in the form of illustrations on the walls advising visitors to pick up the large balls and drop them again. But on the other hand the news cycle is endlessly self renewing, forever young in the sense that there is always another hideous event to fetishize. This piece evoked both possibilities of eternal recurrence of both creative inspiration and destructive passion.

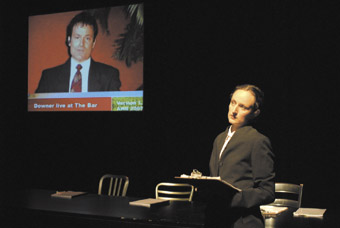

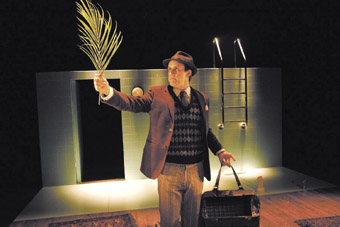

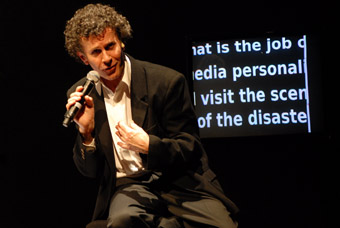

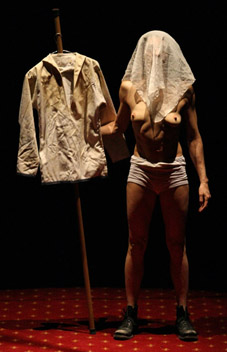

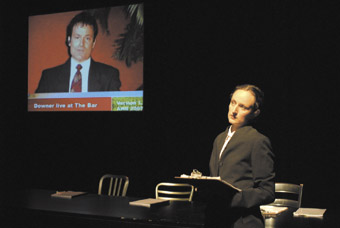

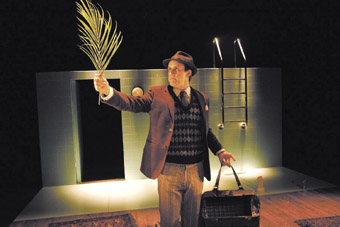

tony schwensen

Tony Schwensen’s work tends to produce a similarly double register of meaning in which the artist’s clown-like persona—The Fat White Straight Bald Guy of his 2005 Performance Space installation—tends to conceal the very real depths of the images he constructs. I’m thinking of the video work he contributed to the ABC for its 50th birthday video portrait commissions dedicated to Peter Jackson, an elite Rugby League champion undone by the trauma of being a childhood victim of abuse. This is a genuinely moving study of the man and the issue that led to his suicide. Schwensen is one of the few artists I know who can successfully marry this contemporary understanding of vernacular Australia and elite art practice without surrendering an authentic point of view in either domain.

In Rise, a hundred hour long “meditation”, Schwensen claimed to be investigating the futility of attempting to live a self-sufficient life in contemporary Western society with its “rampant and thoughtless consumption.” His time consuming tasks were carried out beneath the banner of the wall text: “Hopes None Resolutions None”, Samuel Beckett’s famous contribution to a planned publication of the New Year’s meditations of celebrity writers.

Schwensen’s self-imposed performance tasks were to include continuous manual water desalination but, appropriately for a work examining futility, the pump gave out after nine hours, thrusting the artist into the fundamental experience of Beckett’s characters, the feeling of duration…the negation of activity and the focus on the passing of time. Adorno noted this as the essential characteristic of Beckett’s Endgame in which Clov’s opening words are “Finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished.” Poor old Schwensen must have muttered these words to himself on a few occasions stuck as he was in gallery for 100 hours with a broken pump and nothing to do.

But duration is also the central experience of much recent performance art. In this sense Rise is typical of the kind of work that Schwensen has been developing over the last five years in that it’s a durational performance in which the unfolding of the event over time is doubled by the presence of the artist engaged in repetitive acts on a video monitor. In Rise two monitors were arranged one on top of the other showing the artist’s mouth in close-up enunciating the slogans “Love it” and “Leave it” as in the redneck mantra about Australia (love it or leave it). In Schwensen’s rendering it’s not a choice—you love it and you leave it—something the artist is practising as well as preaching: he has recently relocated to the US. His unique approach to performance art as time-based physical art and mediated self conscious irony is a way of capturing something elemental in the consciousness of the place he is exploring in his work. He will be missed.

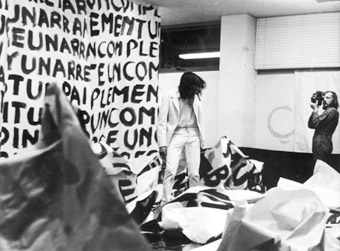

arahmaiani

Arahmaiani’s Make Up or Break Up is a more conventional exhibition of documentary photographs of the artist’s entirely unconventional performative presentations. These are described in her statement as “somewhere between promotions and protests” in which the participants carry a number of wall banners (also featured in the exhibition) “featuring the names of multinational corporations and brands in Malay-Arabic (Jawi) script in public spaces around Sydney.” The sites chosen were at Circular Quay, in the Botanical Gardens and at the Block in Redfern, among other places. Despite their visual appeal these staged events work better as documentation because without knowing what the texts mean there is no possibility of identifying the strategy the artist is employing.

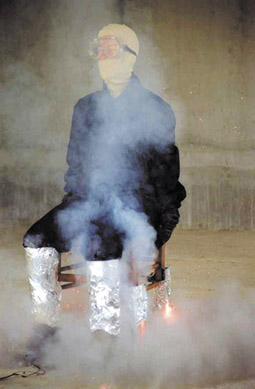

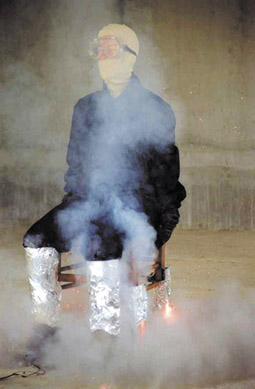

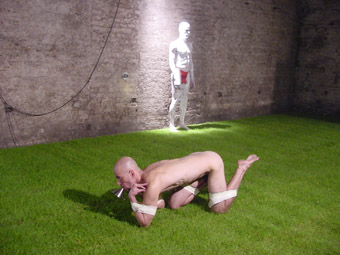

Andre Stitt, Dingo: A treatment towards a new communionsim, performance still

photo Jennifer Leahy, Silversalt; courtesy of the artist

Andre Stitt, Dingo: A treatment towards a new communionsim, performance still

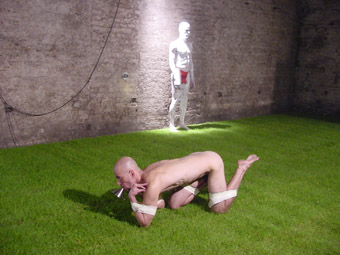

andré stitt

André Stitt’s performance, Dingo: A Treatment towards a new communionism, was more successful in terms of the legibility of its imagery. It involved the artist being locked in a cage with Whumpi the dingo for several hours each day over the three days of the event. The obvious reference is to the Joseph Beuys’ performance, Coyote: I Like America and America Likes Me, performed at Renee Block’s New York gallery in 1974.

I don’t have to tell you that this piece received an enormous amount of media attention in Australia. The usual mix of sensationalism and outright dismissal was perhaps most evident in Sebastian Smee’s response for The Australian on August 10, “Piece without bite made me howl.” In this ‘review’ Smee, who appeared to have been glad-handing everyone the day before at Artspace and enjoying the event, had decided after a moment’s reflection that the work “failed as an interesting piece of performance art for one simple reason: it lacked conviction.” I love it when Murdoch hacks pretend to speak in defence of conviction. “Theatre knows it has to engage”, quoth Smee, while “[p]erformance art subsists on the adolescent idea that it can do whatever it bloody well likes.” Poor boy wanted to be entertained. You might say ‘fair enough’ but to attend a durational performance event and expect theatre is a category error of the most fundamental kind, as any half-conscious arts journalist would be well aware.

Yet the piece was conventionally theatrical in a number of respects with the repetitive use of gesture and props and the establishment of the characters and their relationship at the core of the work. Stitt engaged the dingo in a variety of gestural games, dragging different props: a shirt, a felt blanket, a cane, all references to Beuys. At one point he produced a baby doll from his bag but sensibly didn’t over emphasise this reference. Rather than actively engaging with Stitt the dingo tolerated these activities in the interest, no doubt, of a peaceful life, if not aesthetic harmony. The slow evolution of a relationship between Stitt and the dingo was fascinating to witness as it developed from an initial distrust and fear to a sense of relaxed and playful amusement. Regardless of the larger symbolic associations of this work with respect to the current fragility of the relationship between the Indigenous culture of Australia and the European visitor cultures, Stitt’s achievement was in the immensely subtle development of a complex set of themes—nature/culture, excess/containment, structure/anti-structure—obtained through a slow unfolding of the images in the cage.

If I had more time I would explore the extent to which this work is a re-enactment of Beuys. Of course none of us were there in New York and we have only seen the Beuys performance as video or photographic documentation. In this sense it is perhaps more appropriate to argue that André Stitt is not so much re-enacting Beuys as performing the documentation, as Philip Auslander suggests in a recent paper (“The Performativity of Performance Documentation”, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, 84 Vol 28.3, 2006).

For now it is enough to note that the work itself poses the question which all the works in Aftermath raise in their own way about the extent of the gap between performance and its aftermath in documentation or in installation. These works all show a systematic effort to undermine the opposition between the live encounter with a performance and the encounters with its products, its afterimages, its flashbacks and hard copy memories.

Aftermath, Performance Installations, curator Blair French, artists Guy Benfield, Anne Graham, Franz Ehmann, Tony Schwensen, Arahmaiani, André Stitt, Artpsace, Sydney, July 5-Aug 18

www.artspace.org.au

Aftermath also featured performances by Yiorgos Zafiriou (Aug 16), senVoodoo (Fiona MacGregor, Aña Wojak) and a symposium with Performance Space and RealTime at Carriageworks (Aug 18) – see RealTime 82

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. 52

© Edward Scheer; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

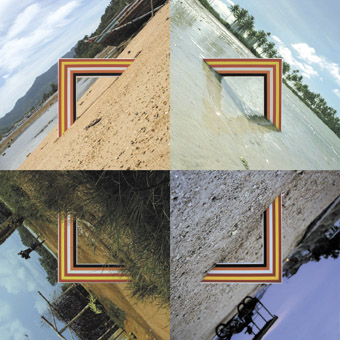

Almost Always Everywhere Apparent, still, Sonia Leber and David Chesworth

OVER THE FIVE YEARS SINCE ACCA OPENED AT SOUTHBANK, MULTIPLE STRUCTURES GENERATING UNEASE AND CLAUSTROPHOBIA HAVE BEEN CONSTRUCTED THAT RECONCILE, AND AT THE SAME TIME, EXPLOIT THE GALLERY’S CAVERNED INTERIOR SPACES. COLLABORATIVE ARTISTS SONIA LEBER AND DAVID CHESWORTH HAVE MOST RECENTLY BUILT SUCH A MICRO-ENVIRONMENT WITH THEIR INSTALLATION, ALMOST ALWAYS EVERYWHERE APPARENT.

A dimly lit foyer acts as a transitional zone between the bloated scale of the ACCA lobby and the core of the installation. This spartan, rectangular void offers a brief moment of stimulus deprivation heightening the sense of immersion that follows.

Open the next door and partially illuminated in neon-pink is a corridor. It veers slightly, concealing its course. Traversing this eerie segment, a digitised crackling noise from above creates an auditory itch. Fragments of choral music also echo in short bursts down the narrow space. The resulting eclectic theatricality is rather like Lara Croft meets the Vatican, in this consecrated low-rent sci-fi set.

Emerging from the passageway some people grin with excitement while others peer out nervously, overwhelmed, into the dark ovoid central space. Five corridors splay out from this shadowy zone, each illuminated by turquoise or lime-green light. Leber and Chesworth seem to replicate the dynamics of Jeremy Bentham’s panoptic prison architectural system, where a central concealed overseer observes a perimeter structure of permanently silhouetted figures.

Accentuated by the splintered choral singing, the installation equally hints at ecclesiastic architecture, of cloisters and interior domes. By combining panoptic and cathedral inspired space, the installation highlights their shared architectonic logic of an omnipresent overseer. Yet, there is a phenomenological disjunction between these two architectural systems.

The church utilises psychologically uplifting atmospherics to reduce bodily awareness, conjuring a sense of being closer to a godly presence. Ceiling details prompt faces to look skyward, reducing the sensation of being grounded, and an often-grandiose scale translates its unconfined nature with a disembodying effect. Conversely Bentham’s panoptic administration, by making the overseen conscious of their silhouettes and of being forever overheard through tin channels, constructed a constant reminder of physical confinement. Leber and Chesworth work the tensions between these two spatial demands.

The abstracted choral sound bites emanate from above where, hanging in the black interior sky of ACCA’s hulking gallery, rests a circular projection screen. This screen hypnotically offers a slowly spinning dull metal propeller behind which warm hued petal shapes move as though the viewer is pushing up through them.

Almost Always Everywhere Apparent, installation

photo John Brash

Almost Always Everywhere Apparent, installation

The quasi-spiritual mood this uplifting movement induces comes with a catch; if contemporary meditation is offered through this simulated, slowed-down centrifuge, the propeller is a barrier that would chop into you. Conjuring physical awareness, the spinning blades deny any sense of potential salvation.

Equally reminiscent of the visceral heaviness of the human body are the noises emitting from the corridors. If the choral music from above seductively evokes the human body in unison and as a hollow instrumental vessel, the noises below come from individual bodies dense with meaty organs from which guttural grunts and groans emerge. Full-bodied gurgling, crying and hissing burst forth as segmented sounds from all directions.

Animalistic yet distinctly human, this repertoire of pre-lingual expression is theatrical in its variety and discordant layering. As gallery-goers veer into the claustral corridors they experience a hiss from the side or an ‘uuuuggghhhhhh’ from the ceiling, like the phantasmic sound track of a ghost ride.

At the dead end of each corridor is a peephole suggesting, as in the panopticon, the opportunity for invisible witness. Lured towards this, figures in silhouette hunch and peer. Observing these observers forefronts the installation’s performative dynamic. The bent over heads appear attached to the wall, bathed in a cool neon glow, their posture suggesting stylised despair, repentance or even some sci-fi cranial procedure.

The videos Leber and Chesworth have concealed behind the peepholes each utilise one of two devices, depicting an upturned hallway so that figures wearing black appear to defy gravity, or showing an overhead perspective (in one, a bird’s eye view of an interior cathedral space). But with these distinctly different perspectival tropes, the artists fail to create an accumulative sense of disorientation. Easily visible monitor edges grounded the images, nullifying the capacity for the videos to further articulate the bodily tensions theatrically constructed by the built space and auditory layering.

Without this concentration of visual detailing the installation threatened to topple into overblown theatrics. Yet, what pulled it back from the brink was the rich complexity of sounds oscillating within its confines. These unstable collisions between spectral and corporeal evocations provided Chesworth and Leber’s phantasmic portal with a surprisingly taut density.

David Chesworth, Sonia Leber, Almost Always Everywhere Apparent, ACCA, Melbourne, Aug 10-Sept 30

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. 54

© Amy Marjoram; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

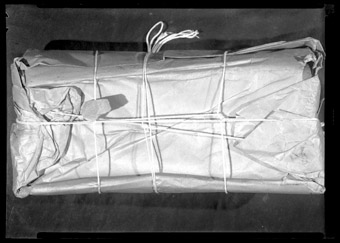

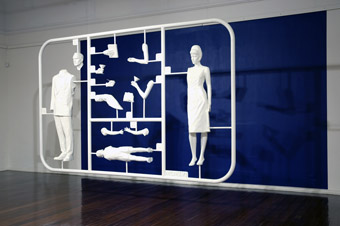

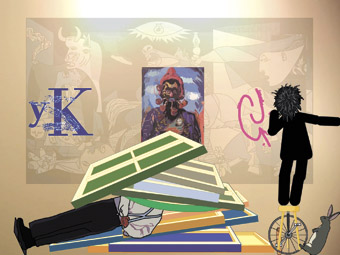

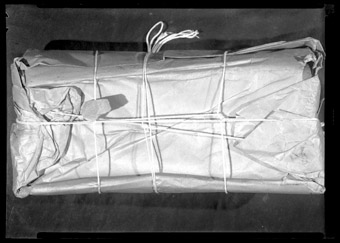

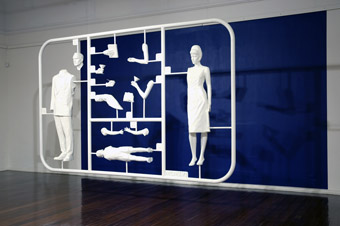

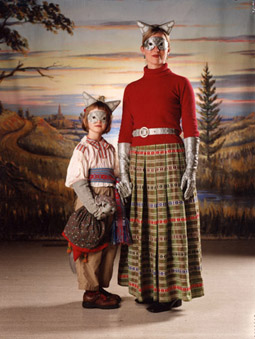

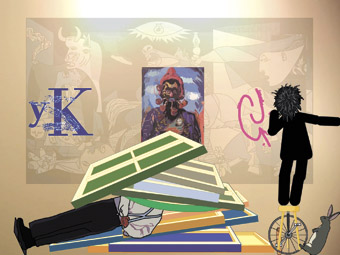

Aurélien Police, Sir Ralph Witkins (2003)

courtesy of the artist

Aurélien Police, Sir Ralph Witkins (2003)

SOMETIMES PERCEIVED AS THE LOVE CHILD OF CYBERPUNK—A DYSTOPIAN STEM OF FANTASY ESPOUSING CYBERNETICS AND REBELLION—STEAMPUNK FINDS ITS NICHE IN A PARALLEL WORLD WHERE STEAM-ERA TECHNOLOGY INVADES THE ULTRA SLICK DEVELOPMENTS OF THE MODERN WORLD. THINK COMPUTER KEYBOARDS MADE FROM OLD TYPEWRITER KEYS, VICTORIAN ERA FASHION AND DIRIGIBLES FLYING HIGH IN THE SKY. STEAMPUNK CROSSES GENRES WITH EASE, ENCOMPASSING LITERATURE, COMICS, FILM, MUSIC AND FASHION. IN ALL ITS FORMS, STEAMPUNK CAN BE GRITTY, INTELLIGENT AND DARKLY COMPLEX.

In an ambitious attempt to bring the genre to a contemporary art audience, Infinite Empire contemplates the wide-ranging creative impact of steampunk. Curated by Carole Hammond and developed under the annual CAST Curatorial Mentorship Program, the exhibition showcases seven artists working across the fields of video, sculpture, jewellery, fashion and digital illustration.

Transformed from the usual white cube into a shadowy cavern with black walls and heavily draped entrance, the CAST gallery momentarily becomes another world. Strange mechanical sounds fill the room, emanating from the Lycette Bros video projection, The Modern Compendium of Miniature Automata (2005). Comparable to a scratchy turn of the century zoological study, the video tracks tiny animals winging and squirming their way across the screen. Each preceded by a species card complete with Latin-inspired name, the creatures resemble microscopic marine life yet their bodies sprout tiny gears, twirling spirals and spinning propellers—the newfound species of a futuristic cesspool.

Intrigued by the techniques used in jewellery and taxidermy, Julia deVille creates Memento Mori imbued with elements of memory, death and resurrection. Clustered inside a glass case swathed in black satin is a series of diminutive trinkets. The trophy head of a diamond-encrusted mouse protrudes from a filigreed picture frame; a small bone and skull rest delicately inside a palm-sized coffin while a severed kingfisher wing longs mournfully for flight: each object echoes a distinctly Victorian fascination with the exotically morbid.

Reflecting on the 19th century devotion to function and mechanical grandeur, furniture maker James Vaughan looks to the guts of Tasmanian power stations, breweries and gas plants for inspiration. Layered with scrupulous detail, Vaughan’s functional objects drip with polished brass and glinting copper. Honeycombed metal panels spread like pathways across the centre of The Brilliant Chamber (2005) while concrete and lead create the sturdy base of Art Gas (2005), a fantastically elegant homage to the architectural ideals of a distant era.

In a similar way, the work of Jon Williamson excels in superb attention to industrial detail. Innovatively exhibited on metal barrels lit from beneath, Williamson’s meticulously crafted jewellery speaks of an aesthetic where beauty appears in a slice of twisted metal. Painstakingly constructed from old typewriter components and electric motors, the work transforms obsolete machinery into futuristic relics wrought with mystery and depth.

Victorian grandeur seeps into Sonia Heap’s collection of pinched and cinched dominatrix-style dresses. More like sculptures than clothing, Heap’s designs combine opulent fabrics, buckles, ribbons and perspex corsets to create a look that is expertly contained yet dangerously malevolent. Possessing a perverse beauty reminiscent of Hans Bellmer’s twisted, eroticised dolls, Heap’s work accentuates the feminine form while demonstrating an innate aggression through the vicious pull and fold of binding fabric.

Alongside the Manga inspired work of animator and illustrator Madeleine Rosca, French artist Aurélien Police relies on the creative scope of digital illustration to document his strange race of mechanical animals and humanoid beasts. Coupling anatomical sketches with yellowed 19th century portraits, Police traverses a futuristic landscape where animals travel on wheels and humans absorb machinery. Augmented by tubes, metal pipes and the rusted innards of industry, characters like Sir Ralph Witkins (2003) and Sybil (2005) exude an eerie familiarity—faintly whispering of what we might become.

Although steampunk has a well-defined style and dedicated fanbase, it is not often seen in art galleries. However, like comic art and graphic novels, steampunk persistently pushes its way into contemporary art. In Infinite Empire, like a prickly rash on the pristine skin of utopia, it’s a satisfying itch to scratch.

Infinite Empire, curator Carole Hammond, CAST Gallery, Hobart, July 28-Aug 26

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. 55

© Briony Downes; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

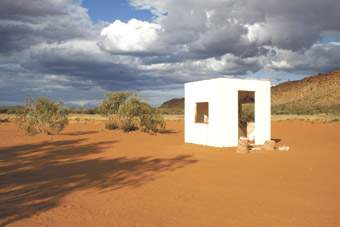

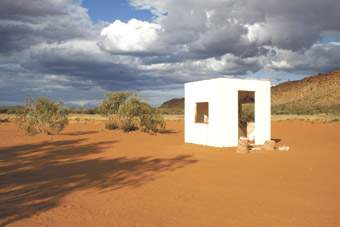

Christine Collins, Riding School for the Cowboys of Doom

I WALK INTO THE AIRY GALLERY, A SHED REALLY, WITH WHITE WALLS AND A CORRUGATED ROOF. BEFORE I TAKE IN THE SCENE I’M MET WITH THE INDISTINGUISHABLE VOICES OF SEVERAL MEN AND THE FRAGMENTS OF A CLIMAXING FILM SCORE. THEN SOMETHING MORE COHERENT, “HOW ABOUT AN EGG?”

In her sound installation, Riding School for the Cowboys of Doom, Christine Collins uses the length of one wall of CACSA’s Project Space to house her work. Four speakers sit on the floor, at least a metre apart, each attached to necessary equipment: AKI, Kenwood, TEAC, Annexe. CDs spin in portable players. The eclectic sound gear emulates the crossing over of eras apparent in the soundscape of four filmic narratives and their relationship to three large images that hang on the wall.

Precise traces of Albrecht Durer’s Four Riders of the Apocalypse (1498) gallop across the tryptic of white primed canvas. Elegant, in flight, the riders move. Towards what? The end of the world: death, famine, war and plague. Beneath them the speakers call, talk of extermination, innocence, of hunters and betrayal. “I wonder if any of these girls will file a complaint about you.” A cat meows. The sound of ice clinking in a scotch glass is unmistakable. The evocations of Hollywood hero and anti-hero are ripe in this landscape. Even if their voices aren’t heard, the Lone Ranger and Dirty Harry are present. Here, the model of American manhood competes with the vigilante for airtime.

You have to get intimate with the speakers in order to hear the film stories in isolation. I lean close to the soft fabric to decipher a line, just in time to be distracted by a familiar voice. Darth Vader? No. It’s Sean Connery in Zardoz, a futuristic western: “You wore a mask. You lead me on, like a game.” The play of these dialogues across the gallery is akin to hide and seek. “If you’re bad enough you’ll die” is followed by “Yes” then “booby trap”, “Yes” then “Goodnight.” A car revs and swamps the Dadaist dialogue.

The technicalities of the exhibition are visible, incorporated. The electrical cords snake along the floor between the speakers. The slender copper thread that hangs from the canvas edges of each apocalyptic rider joins the wires of the sound gear below. The associations between these elements are anachronistic yet, like Collins’ versions of the four riders, the soundscape keeps you moving towards something—perhaps an unfulfillable desire to identify each film, to complete a narrative. But if the dramatic closure of the classic western resurrects hope and order, Collins fragments the protagonists and removes visual contexts, opening up territories of cinematic and, with the four horseman, cultural memory that have no need for resolutions.

It’s been said that the values of Durer’s riders change with the times. By placing them in a cowboy context Collins has inverted their classic meaning. Rather than being ready for action, the riders are left afloat, intermingling with the tales of other men. Collins’ considered juxtapositions of masculinity are quietly comical. I am left wondering if this school of heroes will in fact bring on the apocalypse. Or are they simply doomed to suffer the repeated sounds of each other’s manly actions? Can they get the girl in the end?

Christine Collins, Riding School for the Cowboys of Doom, sound installation, Project Space, Contemporary Arts Centre of South Australia (CACSA), Adelaide, July 20-Aug 26

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. 55

© Jessica Wallace; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Aphids, the Melbourne based company specialising in international cross-artform collaborations, and RealTime, the magazine promoting innovative Australian art to the world in print and online, have come together to offer a residency for an emerging Victorian reviewer in music and sound art.

Part of the Aphids Residencies and Mentoring Program for young and emerging artists, the residency will take the form of a mentorship with a Victorian reviewer and two visits to Sydney to work with the editors of RealTime. Airfares, accommodation and fees will be covered.

Download full information

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg.

Luke Mullins, Katherine Tonkin, The Eisteddfod

photo Brett Boardman

Luke Mullins, Katherine Tonkin, The Eisteddfod

STUCK PIGS SQUEALING’S EISTEDDFOD IS A RIVETTING, CLAUSTROPHOBIC ACCOUNT OF THE MEETING OF INCEST AND SIBLING RIVALRY. LATE ADOLESCENT BROTHER AND SISTER, ABALONE AND GERTURE, HOME ALONE (THEIR PARENTS ARE DEAD), TRAIN UP TO PERFORM MACBETH AND HIS LADY FOR THE LOCAL EISTEDDFOD (FILLING US IN, ON THE WAY, WITH A HISTORY OF THE COMPETITION). HE’S ALL HAMMY AMBITION, SHE APPEARS TO HAVE NONE. IF SHE DID HE WOULD DESTROY IT, UNDERCUTTING AS HE DOES ANY SENSE OF SELF SHE MIGHT HAVE. THERE IS HOWEVER A BOND, FORMED FROM ENFORCED INTIMACY AND THE RITUALISED GAME-PLAYING THEY HAVE EVOLVED. AND THE SEXUAL ABUSE BY THEIR FATHER—IF IT HAPPENED.

Eisteddfod climaxes with a sudden reversal, the sister winning the prize for her performance as Lady Macbeth, the brother collapsing in disbelief, begging her to “be Mum.” The sister, once happy with mediocrity, now has something more—but how much and for how long? Her words from earlier in the play stick: “I want someone to hurt me for a reason.” These children are damaged goods.

Presented in the small space of Belvoir St Downstairs with subtle miking and a clever, hinged stand-alone set-cum-stage which the performers can fold into new spaces, The Eisteddfod is seriously, viciously funny. Written and played larger than life and with a sustained theatrical intensity by Luke Mullins and Katherine Tonkin as directed by Chris Kohn, the play takes us into a world of incest where the lovers are beginning to diverge on their way to complex adulthoods, or an eternal corrupted childhood.

The Eisteddfod premiered in Melbourne in 2004 and was much admired in New York in 2005. It confirms Stuck Pigs Squealing’s radical inventiveness and the acuity and vividness of playwright Lally Katz’s imagination, yielding utterly convincing non-naturalistic dialogue, rich in humour and a revealing perversity in investigating a condition via a flight of fantasy rather than a social document.

Stuck Pigs Squealing, The Eisteddfod, writer Lally Katz, director Chris Kohn, performers Luke Mullins, Katherine Tonkin, designer Adam Gardnir, lighting Richard Vabre, sound designer Jethro Woodward; B Sharp, Belvoir St Downstairs, Sydney, June 6-24

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. onl

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Steve Cuiffo, Maggie Hoffmann, Major Bang

MAJOR BANG, FROM NEW YORK'S THE FOUNDRY THEATRE, IS MINESTRONE THEATRE, A WELL-BREWED, TASTY MIX OF PERFORMATIVE INGREDIENTS—STANDUP, MAGIC, IMPERSONATION, DOCUMENTARY AND MULTIMEDIA THEATRE, AND POSTMODERN DIVERSIONS ABOUT THE NATURE OF THEATRE IN THE FACE OF TERROR. ELSEWHERE IT'S BEEN LABELLED “POLITICAL CABARET.” BUT THERE'S A PLAY INSIDE MAJOR BANG. WOVEN THROUGH A VARIETY OF ROUTINES, IT'S ABOUT A FATHER'S FAILING RELATIONSHIP WITH HIS ADOLESCENT, SCIENTIST SON WHO IS IN THE THRALL OF A FASCIST BOY SCOUT LEADER, MAJOR BANG.

The father works in a food irradiation plant in New York, feels threatened by his son's superior intelligence and inadvertantly allows his security badge to be given by the boy to the scout leader whose intentions are terrorist. The tone is persistently comic, ironic and satirical, the playing virtuosic. Steve Cuiffo is our host, plays father, son and scout leader (in rapid alternations, even using a two-sided costume), mimicks a resurrected Lenny Bruce (rejecting a “war on terror”, he demands “a jihad on terror!”), executes deft magic routines and, with co-performer and fellow host Maggie Hoffman, wickedly corrupts the dialogue of a screened excerpt from the Kevin Costner vehicle, The Bodyguard. Hoffmann plays Cuiffo's boss and potential lover at the factory and demonstrates to us, with a gieger counter-cum-beat-box, that there's radiation in the theatre.

In direct reference to the Kubrick film Dr Strangelove, Major Bang is subtitled How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Dirty Bomb. There's enough destructive energy (the equivalent of “three million chest x-rays” at any time) in the play's food irradiation plant to create another 9/11 horror and there's enough lunacy-at-home to pull it off (the performers tell the true story of a boy who invented a nuclear weapon in the family garage in 1995). The 'war on terror' campaign quickly becomes a nonsense, the US government's fear mongering embodied symbolically in a red backpack that hovers, glowing over the action and soon works its way into the narrative. It explodes, but because the company can't afford anything more than a sound effect, the plot line has to be diverted.

Although it ends with a heavy-handed solemnity after a suspenseful and very funny race to defeat Major Bang, the play's strength resides in its DIY approach to the challenge of dealing with the psychological and political consequences of terrorism. The creative recipe comprises whatever performative means are at hand. From the tacky showground set to card tricks, film clips and wild role doubling, Major Bang, alternatively quaint, arch and incisive, is ultimately a quick-witted lo-tech form of theatrical resistance to the US and (as the performers left us in no doubt) Australian governments' moneyed, monolithic hi-tech paranoia making. As the script puts it: “They tried to scare us but it didn't work. We took all the cars and planes and unattended bags, everything they had made dangerous, and we put them out of reach by turning them into jokes and stories.”

The Foundry Theatre, Major Bang, conceived and created by Melanie Joseph, Steve Cuiffo, Kirk Lynn, writer Kirk Lynn, director Paul Lazar, performers Steve Cuiffo, Maggie Hoffman; Adventures 07, Playhouse, Sydney Opera House, July 17-29

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. on

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Andrew Morrish

photo Heidrun Löhr

Andrew Morrish

“I’M BACK”, DECLARES ANDREW MORRISH, PLAYING TO A WELCOMING OPENING NIGHT AUDIENCE AT THE NEW PERFORMANCE SPACE IN CARRIAGEWORKS AFTER A LONG SOJOURN IN EUROPE AND DESCRIBING HIMSELF AS “A LITTLE MORE RECKLESS”, AGEING AND THEREFORE PERMITTED TO WEAR WHAT TACKY OUTFIT HE WILL. THIS IS MORRISH IN STAND UP MODE, FAST, WISE-CRACKING AND VERY FUNNY, AND WITH AN APPARENT OBSESSIVENESS THAT FITS HIS IMPRO-RIFFING.

From experience we know Morrish in performance is on the road to somewhere. He probably has a pretty good idea where that somewhere is and even how long it might take to get there, if less certain about exactly how. Like a sometimes distracted driver, he’ll chat incessantly while looking out for road signs and landmarks that pop into his head, or not—and then? That’s the nature of improvisation, even this semi-structured variety. No road map. No GPS. Performance is hard enough with lines learnt and moves blocked. In improvisation the road can turn into a tightrope, a path that can run out mid-air, or snap. Then again, improvisors extol the freedom of their medium. Unhindered by various fixities they are psychoanalyst Michael Balint’s “philobats”, in love with the inbetween, preferably without safety nets (Balint, Thrills & Regressions, Maresfield Library, London, 1959). Of course, many an improvisor travels with a rescue kit of fall-back positions, handy set pieces, vocal or physical turns, reliable triggers to carry them through.

“I’m avoiding narrative tonight”, Morrish announces, “but I do have a story. I’ll try to cut it up.” So we accompany him on a journey over the next hour to what turns out to be his mother’s death, but first we hear something of the man she bore: “…an artist, a fat old working class bloke working around Europe getting technique.” The peculiar little Morrish frolics, the discombobulated leaps between verbal dancing, suggest, amusingly as ever, that the technique doses not belong to dance. What’s on his mind is “working class” and how that explains why he can never aspire either to romancing Julia Roberts or applying for an Australia Council grant: he’s working class and “doesn’t deserve better.” He says he’s not bitter that he’s created “a Morrish un-fundable artform: un-copyable, un-ownable sound and movement.” Like the claims made for imrovisation, this is a declaration of independence, as well as of origins. (It would be churlish to dwell on the career safety net offered by performing in state subsidised arts venues. Independence is relative, rarely absolute.)

On the way to his mother’s death, the road does turn to tightrope. We sense a tightening, a somewhat mysterious telephone call motif is established, some words tangle—attributed to the “uncontrollable saliva” of ageing, quips Morrish, making the most of everything—as he does with the CarriagWorks “heritage wall” he realises he is playing against and which nearly takes a bit out of him with one of its left-in-place metal features). Morrish’s quick thinking capacity to pick up on his errors and his tics is played to pomo self-referential advantage, allowing him safe passage to his next point. But suddenly, just as he is about to launch into a key story, his next destination, he realises that it’s not there. All he can do is admit it, and it feels like we’re out there on the tightrope with him. It’s a curiously visceral moment, however brief, before he’s on a roll again.

Morrish is in Europe when he hears of his mother’s impending death. He grapples with Qantas about getting a flight and is criticised by someone for not asking for “compassion discount.” The result is a splendid tirade about a world governed by loyalty points.

The sad conclusion to the story has Morrish transform, in a way, into his mother. He unzips his jacket to reveal a floral frock, and he dances a little dance and “she slips away.” It’s a moment of quiet but intense, considered theatricality.

The balance between moment and momentum in Morrish’s performance was finely held, even the moments of near fall accentuating the accomplished art of a fine philobat.

Andrew Morrish, Solo 1, Letting off Steam, Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, May 25

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. on

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Input, updating, memory, computation/comprehension, output. These are what you need for interactivity, writes Jolt artistic director James Hullick in his program notes for Interactacon, an event focused on interaction between humans and computers.

Robin Fox, his face screen-lit, holds a detonator in each hand—game-like t-box sensor interface controllers. A barrage of rapid-fire sliced-in-a-blender sounds mixed with moments of Looney Tunes hilarity, sheets of sheer noise and room rumbling bass move from left to right at dizzying speeds. Fox’s relative stillness contrasts with the moment-to-moment interaction with his computer via the hand-held interfaces, much like a virtuosic jazz musician in the throes of a blistering solo.

The program notes reveal that the software has its own “behavioural” tendencies that “fight back” Fox's inputting. The result suggests war, conversation, laughter, dance, play and love-making—all at a hair-raising, impossible pace, if you can stay with it (a handful of people drop out of the battle early on). Huge dynamic shifts move over and slice into each other with momentary suspensions and windings up and down while Fox’s fingers twitch at the controls.

In Maculae, Natasha Anderson’s gestures are more theatrical and considered. The sensors she's attached to an impressive contrabass recorder allow her to trigger sounds from her playing as well as to add gestural input alongside vocal croaks and clicks. To one side small details from “self-portraits” and the interior of a room are screened, fading in and out and also triggered by her interaction with her instrument.

In contrast to Fox’s minimal spacings between sounds, Anderson creates a more open sonic field where languid movements and long tones are punctuated by sharp spikes of sound and gesture. The processing adds fleeting, decaying loops, watery masses, varying textures and brief abrupt buzzings, creating a cumulative rendering of a kind of subterranean or interior space.

Hullick’s first contribution to the event is Sk-eylike Mind, an interactive score performed by Bolt and comprising flute, clarinet, sax, double bass, percussion and viola. The projected score unfolds in real time displaying, among other things, pitch, directions and rests. Long overlapping tonal notes are textured with shorter gestural events. “Like a machine hum” and “let it ring” are some of the more curious directions in the score.

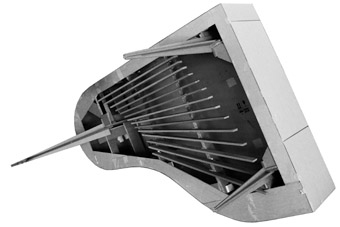

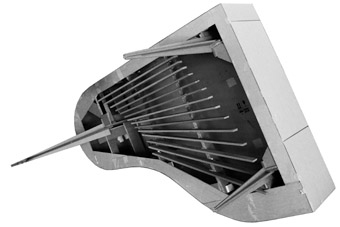

Hullick’s second contribution also features projected notation—bright dots on a black background are revealed left to right at various heights. The Crank-A-Maphone (a computer-operated instrument comprising a triangular frame within which sit Tibetan bowls, chimes, bells and more, see RT79) realises the score while a series of miked spherical glass objects appear to be improvised on by The Amplified Elephants, an “inter-ability” ensemble that has grown out of the Footscray Community Arts Centre’s Artlife program. The result is a spacious landscape of soft bell-like sounds with occasional metallic punctuations.

Without the aid of the program notes it's difficult to deduce the modes of interaction inherent in some of the performances. Sometimes the interactivity is visible, sometimes not, for example in how the functioning of the Crank-A-Maphone relates to the projected score. But does the audience need to be privy to the workings of interactivity? Isn't it about the overall effect of the interactivity, and especially its sonic outcome? These interesting questions are being posed in events like Interacton and in the discovery of new modes of composing and playing through human and computer interaction.

Interactacon, Jolt Winter Series Concert 4, artistic director James Hullick, artists Robin Fox, Natasha Anderson, James Hullick, Bolt Musicians (David Thomas, Martin Mackeras, Andy Williamson, Bernie The Man, Peter Neville, Erkii Veltheim), instrument engineer Richie Allen, The Amplified Elephants (June Bentley, Jay Euesden, Liz Hofbauer, Robyn McGrath, Enza Pratico), designer Emile Zile; 45 Downstairs, Melbourne, August 23

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg. on

© Dean Linguey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

My Kid Could Paint That

WHEN I WAS A FOUR-YEAR-OLD MY MUM OFTEN TOOK ME TO THE ART GALLERY. I QUITE LIKED THE IMPRESSIONISTS, THE VAN GOGHS, THAT FREDERICK MCCUBBIN WITH A WOMAN HOLDING HER BABY ON HER LAP. I COULD UNDERSTAND THEM. THE PICASSOS I WASN’T SO KEEN ON. AND ANYTHING WITH A RED TRIANGLE ON A WHITE CANVAS, SPLODGES OF PAINT THROWN ON OR A HORIZONTAL LINE DRIBBLING ACROSS WITH A SHAKY HAND MET WITH ANGER AND FRUSTRATION, AND LOTS OF DEMANDS TO MY MOTHER. “WHY IS THAT HANGING IN THE GALLERY! I COULD DO THAT!” SHE ALWAYS HAD THE SAME REPLY: “MAYBE, BUT YOU DIDN’T.”

Meet another four-year-old. Marla. She’s certainly done it. She’s sold over $300,000 worth of abstract art. Oprah Winfrey’s on the phone. Crayola’s keen to be a sponsor. Her buyers talk of her artwork in hushed tones as if the canvases have been touched by the hands of an angel. They imagine the works as full of her childlike spirit, her innocence. A man sees a door opening onto new worlds. A woman just loves the Mickey Mouse ears. As Michael Kimmelman, New York Times chief art critic says in the film, “…no one is saying fuck you in this picture. They’re just saying I’m a happy girl who likes painting.” But Marla doesn’t want to expound on the symbolism or lack of irony in her work. “No!” is her firm answer whenever doco-maker Amir Bar-Lev asks whether she wants to talk about her art. And Marla doesn’t seem to want to make much art either, not on camera anyway, and not in the colours and techniques she’s expected to.

When Bar-Lev first gets filming, he believes in the work of Marla; she’s at the (short) peak of her success. Parents Mark (a painter himself, keen to push his child into the limelight) and Laura (“if this ends today, I’ll be happy”) let him into their home and the often cynical world of their friend, gallery owner and hyper-realist painter Anthony Brunelli, who sees the possibilities (“these kids could be on a Gap commercial”) and exploits them for all they’re worth.

As Bar-Lev pushes deeper, and the media begin to turn after an expose on CBS’s 60 Minutes claiming she’s a fraud (they plant a hidden camera in the Olmstead house), the filmmaker, along with the audience, starts to have doubts—is she really doing the artwork?; is her father directing or bullying?; does he finish them off himself?; why can’t she seem to create such masterpieces for the camera? But Marla’s dad has read the literature and is always one step ahead. He tells the filmmaker that once you measure something, you alter it. The only problem for him is, it’s hard to control the wayward conversation of a four-year-old. Much is revealed by Marla’s younger brother Zane, who brags: “When I was at the hospital, when I was in mummy’s tummy, I was painting on the table.” Now there’s a child prodigy: I imagine the artworks nestled in his mum’s womb, protected like cave paintings.

Like Maciek Wszelaki's great Australian doco Original Schtick (1999), which covered similar territory about the artist Bob Fischer, this film isn’t really so interested in whether the art’s authentic or not, but at the public and media reaction when things turn sour. Bar-Lev digs into the underlying fears of a community who have no rules to play by when judging whether art is ‘good’ or ‘bad’, who distrust an artworld based on increasing commercialism and who still see art as representing some sort of ‘truth.' If a child can paint a masterpiece, where are the standards by which to judge a Pollock? It’s an old debate but it still seems to upset people. A lot. After 60 Minutes airs, Marla’s parents are assaulted and attacked via email as traitors, even as sinners marked to burn in hell. As Kimmelman points out, people take the idea of modern art as an insult, it says ‘you’re stupid and I’m not’, breeding a collective insecurity.

But what I’m left debating is the widespread desperate desire to dress up a child in adult clothes, spin her around in high heels, and then strip her bare, exposed to the world. But then, here I am in the audience, devouring this wonderful documentary like a wolf, hungry for more to chew up and spit out…

My Kid Could Paint That, director, producer Amir Bar-Lev, editors John Walter, Michael Levine, directors of photography Matt Boyd, Nelson Hume, Bill Turnley, original score Rondo Brothers, A&E Indie Films [US]

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg.

© Kirsten Krauth; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Jo Lancaster, Acrobat

photo John Sones

Jo Lancaster, Acrobat

JO LANCASTER APPEARS ALONE IN AN UNADORNED PERFORMANCE SPACE, NAKED BAR A PAIR OF BLUNDSTONE BOOTS. SHE STROLLS OVER TO A BASKET, PULLS ON UNDERWEAR AND TURNS, TONGUE IN CHEEK, BRANDISHING HER BOTTOM AT THE AUDIENCE AND WHIRLING A HULA HOOP. THERE IS A SENSE OF MISCHIEVOUSNESS AS SHE PLAYS ON THE AUDIENCE’S FEELING OF AWKWARDNESS. ACROBAT’S SMALLER, POORER, CHEAPER CHALLENGES CONVENTIONAL ROLES FOR THE BODY AND THE PHYSICAL EXPECTATIONS PLACED ON IT, QUESTIONING WHAT HAPPENS WHEN WE SHED OUR INHIBITIONS ALONG WITH OUR CLOTHING AND EXPOSE THE VULNERABLE BODIES BENEATH.

Lancaster’s fun-loving opening tumbles, turns and spins are suddenly interrupted by a marriage to a clothes horse. This woman’s freedom is abruptly exchanged for a vacuum cleaner thrust into her hands by a stage assistant. There is something eerie about the way she rocks it like a baby. Now, the cold, hard metallic object restricts her freedom as it lies cradled in her arms. In a final mockery of domesticity, she attaches the suction valve of the vacuum to her breast, creating an image of a suckling parasite.

Lancaster, Simon Yates and Mozes Taplin each perform solo acts exploring how the body is shaped and re-shaped by warring social forces. As in the theories of Foucault, the body becomes a surface on which events are inscribed. The play between the naked body and the meaning of clothing threads through the work.

Placing a giant sheet of butcher’s paper on the floor, Lancaster creases the sheet as if practising origami. She reveals her creation: a dress. It is striking the way domesticity keeps defining her actions. Even now she is, in a sense, folding her own clothes. She holds the dress against her body and, in big child-like scrawling texta, draws scenes of typical suburbia. In a violent movement she suddenly rips a hole in the dress over her genitalia, exposing a crude gash amongst the pretty scenes of flora and picket fences.

With the appearance of Mozes Taplin comes a magical exploration of the contrast between the public and private self. He brandishes a scarf and appears to lose it in various parts of his body. The trick turns into a flirty striptease that tests the boundaries between private whim and public performance.

In the starkest scene of all Taplin, tautly entwined by a rope, tumbles from a height, the cord cutting into and marking his flesh. The temporary etchings that cover his skin remind us of the way people score and brand their bodies as a form of self- expression. ‘Blood’ (in the form of paint) seeps down the rope and, suddenly, it is everywhere, splattering the performance space. It is a violent act and the painfulness of the scene is underscored by a haunting sound-score by Tim Barrass. Sounds of insatiable hunger, gulping and sucking, echo through the room like a soul being wrung from its body. Pre-recorded and live sounds are mixed by the composer onstage creating a metallic, electronic rhapsody.

In another twist to the categories on interior and exterior, traditional ‘behind the scenes’ artists appear onstage, integrated into the performance. The stage operator, Alex White, drolly walks across the space with a placard reading “And now for something a bit lighter.” At another point the audience watch as the performers, with the aid of the stage hands, elaborately and dramatically set up a catapult act using a punching bag as the weight, only to parody the feat in a contrived anti-climax.

Smaller, poorer, cheaper is hilarious and frank physical theatre performance in which the body is constantly revealed in more ways than one. We leave the theatre with a heightened awareness of what we could achieve with our own.

Acrobat, Smaller poorer cheaper, Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sydney, March 28-April 1

RealTime issue #81 Oct-Nov 2007 pg.

© Kavita Bedford; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Melissa Hirsch, de natured

photo Fiona Morrison

Melissa Hirsch, de natured

Election-propelled politicians play at being visionaries of the environment, Aboriginal well-being, water management and housing shortages. But, as we’ve come to expect of recent elections [and Opposition leader Kevin Rudd’s strategy of not messing with established perceptions], no one will lead on the arts [‘elitist’ and ‘adequately funded’]. In the universities, tensions between art and institution are reaching critical mass [see our annual arts education feature, p13-28]. The absorption of arts training schools into the constantly restructured and managerialist university sector, proposed ‘generalist’ undergraduate degrees and the diminution of the humanities deal heavy blows to the arts—like being hit by an immoveable force. In the world outside the academy, federal politics has likewise belted into the arts—not least with the velvet glove of indifference. Kel Glaister’s Immovable Object [exhibited at Bus Gallery as part of the Making Space celebration of Melbourne artist-run-initiatives, p53] seemed an apt cover image for this edition, not least because its ‘icy’ coating is melting and the object, once a violent force, seems not quite so immovable despite the damage done. Can the arts resist the forces arrayed against them and repair the damage done? Do we have the tools? Fibre artist Melissa Hirsch’s “climate neutral status” de natured at Darwin’s 24HR art [image on this page and see p39] evokes in its flax-woven tools not only technological transience but also the creative capacities for renewal.

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 1

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

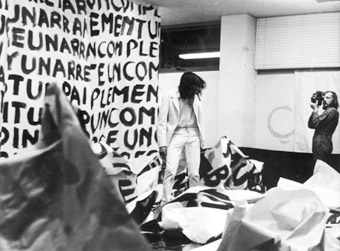

Miguel Perreira and Manuel Vason, Collaboration #2

courtesy of the artist

Miguel Perreira and Manuel Vason, Collaboration #2

“IT’S A LOVE STORY,” SHOUTS FRANKO B, INCREASINGLY AGITATED AND VERBOSE, “IT’S ALSO A STORY OF HATE. IT’S LIKE I LOVE YOU, BUT SOMETIMES I WANNA FUCKIN’ KILL YOU.”

Here we are at the symposium attached to Encounters, Manuel Vason’s exhibition of photographs at Arnolfini in Bristol. The pictures were produced as joint projects with the great, the good, the bad and the beautiful of the live art world and Franko B is reflecting (loudly) upon the nature of collaboration and the ethical difficulties of sharing a work. Sometimes, he says, when a performer needs an image it would be easier for them to “give a photographer three grand” and then walk away with the negatives. But this is not what Manuel Vason does.

five times—no more

How best to describe the creative process initiated by Vason? The word ‘symbiotic’ might sound a wee bit OTT, conjuring up images of the photographer as some sort of arty pilot fish swimming about the gills of Ron Athey, Monica Tichacek or Luiz de Abreu. But Vason originally came to the world of performance as an ingénue, almost completely unfamiliar with the live art territory, stunned by these odd bodies in extreme contexts, bewitched by the unspeakable and the seemingly unrecordable. And it’s this challenge that propels Vason’s own practice forward as he takes some serious time to get to know his subjects: discussing their work at length, going on little adventures, repeatedly shooting the breeze before shooting a single frame. When the crucial moment of capture finally arrives Vason creates a scant five exposures. Sure, as the shoot progresses Polaroids litter the floor, consulted, criticised…but when the shutter atop the tripod snaps, it does so five times—no more. For subject and photographer, the pressure is on.

These exposures are not necessarily representations of an existing performance, not ‘documentation’ in the sense of the word usually employed by live artists. They are not the meta-data of a moment, shot for funding bodies, archivists or future collaborators. Whilst familiar motifs and concepts may well crop up (Sachiko Abe’s gossamer webs of cut-up paper, Veenus Vortex surrounded by charred carboniferous debris), these are performances for the camera, unique and brief—as brief as the snap of a shutter. A selection of these moments has been collected into a book (also entitled Encounters) published by Arnolfini, and its launch is accompanied by several related events: the aforementioned symposium; performances by three of Vason’s collaborators; and an unusually dynamic exhibition of 16 large prints. It’s an immersive weekend.

Monika Tichacek and Manuel Vason, Collaboration #2

courtesy of the artist

Monika Tichacek and Manuel Vason, Collaboration #2

controlled viewing

In Douglas Adams’ and John Lloyd’s comic dictionary The Meaning Of Liff, a ‘Frolesworth’ is “the amount of time one must spend looking at each picture in an art gallery in order that everyone else doesn’t think you’re a complete moron.” Take it from me: the Encounters exhibition seriously messes with your Frolesworth. The gallery space is in semi-darkness and rigged so that each print is spotlit only in the physical presence of a viewer: pressure sensitive pads depress beneath your feet, and a light gently warms over both you and the nearest image. You’re a little theatrical show of your own, you and that photograph. Move along and the light thins to nothing. Try to step closer? The light fizzles away.

On my first viewing I’m treated to my own—strictly unofficial—performance by Franko B. He strides up to the remarkable domineering image of his own whitened, blood-flecked face and appraises it from a variety of angles; except he can’t. He finds out pretty rapidly that he’s not allowed to stand close-up next to his own right cheek, or assay his majesty from a distance. The light only loves him when he’s upon the appointed spot, when he begs an audience with himself. Franko B harrumphs, shakes his head, and moves on: and I can see that interfering with one of the central freedoms of gallery-going may well annoy those who like to get so close they can smell the pixels, or stand so far back they’re practically in another postal code. Equally, you could argue that the technical trickery makes Encounters a bit like walking around iPhoto made flesh, a giant slideshow by anything but name. But for me, the staging has a remarkably positive effect: presented in such a uniform manner, without explanation or index cards, these frameless pictures develop frames uniquely their own.

As you walk around the gallery each approach involves a different negotiation. Here’s Alastair MacLennan, enthroned atop a cliff-face of rubbish and muck on a Belfast landfill, king of the seagulls. The print is one of the more pronounced enlargements and from this panoramic distance he appears foreign, benign…you feel the desire to approach and the instinct to turn away, simultaneously. Here’s Kira O’Reilly holding a slaughtered pig in a pieta, surrounded by a motley collection of Svankmajer-like taxidermy, lilies and pickled specimens; much like the performance that inspired it (inthewrongplaceness) the picture is oddly inviting, sweet like the amine tang of decaying flesh, whispering of a great many mortalities.

Here’s Marcela Levi, her steady unrelenting gaze above a mouth made into some alien orifice by means of a brace of thin black hairgrips, a sphincter dentata. I feel the need to return to this picture and step more carefully, more gently on the pressure point than I did the first time…as if I hadn’t properly paid my respects. In contrast, I feel like I’m seriously intruding upon the tarred-and-feathered Miguel Pereira, sad, pathetic and plastered against a blank wall like a dying bird. And the portrait of Anne Seagrave, channelling an almost visible electricity through clenched fingers and arms at right angles, invites me into a sort of meditative response of my own, rocking on the light switch, moving the steel grey image in and out of darkness. The freedom of interaction is much more pronounced than it might at first appear; upon leaving, we’re even invited to give these photographs (uniformly named Collaboration) titles of our own, scrawling ideas on postcards. It’s fruitful stuff: the images invite stories, backstories, the non-sequiturs of dreams.

tell and show

The symposium is much concerned with the collected problems of documenting the live event and the interesting complications generated by the beguiling love stories Vason and his collaborators have fashioned. Rebecca Schneider delivers a keynote speech as mischievous and sparkling as her contribution to Vason’s book, musing upon the tease of photography: “The photograph says: you were never there, and even if you think you were, you probably weren’t.”

Luckily, over the course of two days, we’re given the opportunity to ‘be there’ in no uncertain terms. Niko Raes produces Shattered Dreams, a compelling performance in which his naked body, suspended from the ceiling, is rigged so as to confound itself: as one limb falls, another must rise and vice versa, making a Sisyphean task of attaining any repose. His slow, deliberate movements have the constancy of Brownian motion and, ultimately, a very visible pain, Raes’ breath becoming increasingly laboured. The tension is only spoilt by some distracting and somewhat pointless analogue bloops and burbles on the soundtrack.

Veenus Vortex’s Worth Her Weight is a durational performance examining the personal language of desire and mythological representations of the body. A prone female form is slowly gilded over the course of several hours, the gold leaf attached by means of raw egg and saliva. Whilst the central image of a female form entwined around a cloven-hoofed double of herself is a remarkable one, the room is full of all sorts of vague symbols and ideas and for an examination of desire it seems strangely unfocussed; the entire atmosphere again wrecked by an unpleasant clunky collage of a soundtrack, this time played so loud it practically kicks your cochlea to death.

The final performance of the weekend is Ecstatic by Ron Athey and is, in contrast, a model of extreme, almost overwhelming focus. On a central altar, Athey vigorously brushes a wig of blonde hair on his head. This action somehow punctures wounds beneath the hairpiece, leading to a flow of blood. He then removes two glass panes from the end of the dais and laboriously, slowly, slats them back and forth across his naked body, over and under each other, his blood forming coagulating patterns on the glass like fluid fixed upon microscope slides. He then leaves. That is the sum of his actions, and despite the fact that mid-show the Arnolfini fire alarm sounds and the work halts for a few heartstopping minutes—a moment that feels like a slap to the face—the visceral simplicity of the performance prompts in me a series of reactions I can only describe as synaesthetic; I can almost smell the iron in the blood dripping across the raised podium, the motes of dust spilling from Athey’s wig are like tumbling musical notes, and by the end of this brief, unique moment I’m light in the head. I was there. And even if I thought I wasn’t, I probably was.

Manuel Vason, Encounters, Arnolfini, Bristol, UK, June 6-July 1

www.manuelvason.com

Encounters, Manuel Vason, Performance, Photography, Collaboration, Dominic Johnson ed, Arnolfini Gallery Ltd, UK 2007

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 2,3

© Tim Atack; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

stolen TVs, from Life After Wartime

THE ROAD TO SEEING HERSELF AS A MEDIA ARTIST HAS BEEN A FASCINATING ONE FOR KATE RICHARDS WHO HAS TWO SHOWS AT SYDNEY’S PERFORMANCE SPACE IN AUGUST-SEPTEMBER. BOTH WORKS ARE TECHNOLOGICALLY SOPHISTICATED, COLLABORATIVE CREATIONS INVOLVING NOT ONLY SOFTWARE AND HARDWARE INNOVATIONS BUT ALSO ADVANCES IN DISPLAY AND PERFORMANCE METHODOLOGY. BUT IT WAS SUPER 8 THAT KICKSTARTED RICHARD’S COMMERCIAL AND ARTISTIC CAREER.

The first work, Bystander, is the latest manifestation of Life After Wartime, a suite of interactive media works created with Ross Gibson around a Sydney archive of crime scene photographs from 1945-60. This time the work will be experienced as an immersive installation after earlier incarnations as CD-ROM, gallery exhibition (which drew a huge attendance at the Justice and Police Museum, 1999-2000) and performance. Twelve visitors at a time will enter a space made up of five screens. This time, the mobility and attentiveness of the audience will prompt a computer to decide what to release of the crime scene images and narratives.

Richards’ other collaboration is Wayfarer, with Martyn Coutts, a game-based performance in which each of four audience teams investigates an unfamiliar space through images relayed by a performer whom the team direct using their voices.

the making of the artist

Sydney in the late 1970s fuelled the young Richards, just out of high school and excited by conceptualism at Sydney College of the Arts, where her sister was studying, by what people were doing at Alexander Mackie Studio, at Side Effects and the Sydney Filmmakers’ Co-op. “It was a very fruitful period. I was lucky enough to get into what later became the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) and I started working in film, which I loved, and later living in the UK I learned video through the community video sector. But I always had a hankering to do more conceptual, experimental types of work, and I didn’t feel I fitted in at UTS which was at that stage teaching a more film industry model, although a lot of good people did come out of that.”

Richards maintained her experimental film and video practice, but while teaching at the College of Fine Arts (COFA) and doing her Masters degree, “I had a concept for a work that was not linear. And, I thought, ‘How am I going to manage this?’ Bill Seaman, the American media artist, was teaching at the COFA at the time and was my supervisor and said, ‘This sounds like a CD-ROM.’ And I was away! With a solid media production background I’ve always had a horses for courses attitude—choose the media that’s going to fit the concept. What I liked about interactive multimedia was that you could bring lots of extant media to it—cinema, sound, illustration, painting and typography. And there was also a role for the audience in determining outcomes or in navigating—I liked this fourth dimension. I’ve always enjoyed working with technology so it didn’t faze me too much.”

But Richards was wary of seeing herself as an artist even though in the early 80s she’d been well known in Super 8 circles and had secured grants. “I didn’t feel that confident as a young artist. I found creativity a scary, deep thing…I’m a bit of a late bloomer.” The impulse to focus on her artistry came after eight years of teaching at COFA, as well as in the Indigenous filmmaking course at the Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS), Metro Screen and full time at UTS in media production.

“I was burnt out from executive producing something like 80 different projects a year and from not doing my own projects. And I’d lost the creative drive.” Richards turned to freelance work including two years as multimedia producer for the NSW Historic Houses Trust based at the Museum of Sydney. Nowadays, working on her own projects and in collaborative ventures, Richards declares, “I define myself as a media artist.” As well as the Performance Space shows, she’s exhibiting a series of photographs at the Australian Centre for Photography in October and is working on a video for next year.

Above all, Richards reveals, “It’s interactivity, as a commercial producer or as an artist, that continues to stretch me. I learn different techniques, I work with different contractors and crafts people.”

Bystander, Kate Richards, Ross Gibson

bystander

Richards describes Life After Wartime as “a suite we’ve worked on together since 1999. Ross Gibson started a couple of years earlier researching the material. We have a database of 3,000 images and about 1,500 texts from Ross as well as sounds [incuding original music by Chris Abrahams and sound design by Greg White]. We were interested in different forms of display, different forms of interactivity design, so the audience would get different affects from the same sort of material. The visual and the sound design is similar across the whole suite—it’s the interactivity design and the combinatory strategies that differ in terms of the way the audience engages.”

Explaining how this new version of Life After Wartime works, Richards says, “Bystander is based on the notion of a generative world. ‘World’ is a common notion in fairly sophisticated interactivity. You create an environment that has very simple rules and it knows what to do under particular conditions. This allows for emergent behaviour which could be defined as simple rules giving form to complex behaviours. So you try to keep the rules as simple as possible for the World. In Bystander, the world only has a few characteristics. It’s on a 45-minute cycle. Every 20 seconds it pumps out a narrative text.”

Richards emphasises that “there is no interactivity apart from where audience bodies are and how they’re moving individually and collectively.” It’s the World which is asking, “Where am I in the 45-minute time cycle? What’s that text that’s just rolled out? How is the audience behaving, how still or robust or disruptive? And then using a valency or a gravitational idea it will draw a number of images or texts to cluster around that text. It’s choosing them on the fly from the database. If the World finds itself at a certain point in the cycle and the audience behave in a certain way, it chooses a whole lot of images about Kings Cross…or a bunch of images designated as having high narrativity. The rules change over the cycle. It’s a World sending you stuff, we don’t control what comes out, just the rules.”

The five-sided space was designed by media artist Tim Gruchy who, says Richards, “with his gallery experience and knowing that most galleries don’t have the equipment we need, suggested we make Bystander portable and self-sufficient. The frame and screen have been fabricated by professional screen makers. Five computers run the work, one has the brains (the World) and the others have to prepare the images for the five projectors as well as the sound. We made the whole thing as a kit.”

Richards adds, “The beauty of this system is that we could put someone else’s database in. Part of the research imperative of the project, which was funded by an Australian Research Council grant, was how do you create an environment that enables you to put a collection in and find the patterns. And how to pace it to suit the collection.

“We made Bystander respond positively to attentiveness because the material demands it. If the 12 people visiting at a time are quiet, more content is revealed, if noisy, less.”

wayfarer

Wayfarer has been three years in development and has physical theatre performers at its centre. Richards has always been attracted to engaging with performers, working with them on film and for voiceovers: “and I’m a bit of a frustrated performer myself even though it terrifies me.”

The work was initially conceived in 2004 at Time_Place_Space [the laboratory which brought together media artists and performers over five years]: “I teamed up with Martyn Coutts and we got on like a house on fire. He’s a physical performer from Tasmania interested in technology, he’s done a few technological projects and has strong theatre production management skills. We put together a concept in about an hour from a provocation from the workshop convenors, but it’s been through various changes since.”

Richards describes Wayfarer as combining “the exploration of a strange space, live performance and interesting technologies. It’s effectively a live game. The audience groups each have a player whom they drive using voice. The conceit is that the audience is outside and the performer inside a building they don’t know. It’s timely to premiere it at CarriageWorks because a lot people don’t know the back of the building yet.”

The performers move through the building wearing small chest-mounted computers “which send streamed video to our software and audio through VOIP to the audience who communicate via microphone. The performers also have RFID readers that can read tags (which trigger films about the site), like bar codes, in the building, and also so the site knows where they are. There are key game elements—time limits, issues of agency, how much for the performers, how much for the audience. There’s a series of tasks and goals you have to achieve to finish the game and beat the clock.”

The teams will operate near each other in the massive CarriageWorks foyer, working to a large screen with their voices: “Voice is the most flexible interface you can have. Anything you say is a potential action.” As for performer interplay, “If and when the performers intersect, the software splits the screen, so that the audience see up to four points of view.”

Richards says she has been particularly influenced by the UK’s Blast Theory (see p6): “When you participate in one of their works, it alters your consciousness because they’ve got a stong social enquiry imperative, the works are well designed and not always dependent on hardware—it might be about team mentality, for example, having to ‘buddy up’ with someone for a long period. We’d like our audience to be confronted by their own behaviour, their improvising, their relationship with a performer. We want the stakes to be high, an ethical spectacle. We like spectacle, we like games but we want something gritty, to be challenged. We want moral dilemmas.”

As with Bystander, Richards says that the hardware and software can be adapted for various users, for example text-driven theatre or community projects. As for the design, she admits, “I understand it in principle but it’s hard until it’s functional.” It’s a long way away from the mechanics of Super 8, but clearly for Richards a road well worth taking.

Above all, Kate Richards is emphatic that “immersive” doesn’t mean having to push buttons, learn rules, make mechanical decisions or rely just on the intellect. “It’s in the way you move. It’s in your voice and what you say.” The game is on. Enter the ethical spectacle. Complexity.

Bystander, artists Ross Gibson, Kate Richards, visual design Aaron Seymour, interactive sound design Greg White, senior programmer & engineer Daniel Heckenberg, sound programmer Jon Drummond, installation design Tim Gruchy, Performance Space, Aug 8-Sept 9 www.lifeafterwartime.com; Wayfarer, artists Kate Richards, Martyn Coutts, software design and programing Jon Drummond, technical producer & designer Mr Snow, Performance Space, CarriageWorks, Sept 5-8, www.performancespace.com.au

RealTime issue #80 Aug-Sept 2007 pg. 4

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

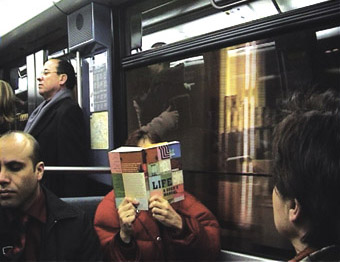

Pocket Film Festival

THE MOBILE PHONE IS A SHRILL INTRUDER. IT UNSETTLES MY SLEEP, INTERRUPTS MY CONVERSATIONS AND PROMPTS A MID-STRIDE FRANTIC BAG FOSSICK. IN JUNE I TRAVELLED TO PARIS IN PURSUIT OF THE BROADER CULTURAL DISRUPTIONS THAT THE MOBILE PHONE MIGHT BE CAUSING.

Now in its third year, the International Pocket Film Festival 07, hosted by the Pompidou Centre, presented a plethora of forums and creative projects that were made with, shown on, or developed thanks to the mobile phone.

France seems an appropriate home for this grainy new bloom of filmmaking. The streets of Paris are the subject for a new generation of filmmakers, but now pixilated to the point of abstraction with truth shakier than ever at 15 frames per second. Yves Gallard, coordinator of the festival’s international program, likens the potential of mobile films to the freedoms experienced by early Super 8 filmmakers, thus squarely and safely placing the festival within a canon of French national cinema. It is not surprising then that film director Claude Miller, who started out assisting Bresson, Godard and Truffaut, headed up the jury for best big screen film shot on mobile phone.

Heidi Tikka's Births, Pocket Film Festival

broadcasting intimacy

In one of the many forums, Heidi Tikka of Mcult, Finland, presented Births, a mobile service experiment that placed camera phones in the hands of new mothers in Helsinki maternity hospitals. Tikka frames her work as artistic social research into mobile applications.The stills taken on these phone cameras were projected in prominent public spaces: babies catapulted from recent constriction in the womb to 20x magnification on a city wall. Tikka explains that we previously announced births in the local newspaper: a few words released into the public sphere for those who know the family. Her project makes the celebration of birth a broader community experience. As viewer I have no idea who these slimy little people are but their struggling first breaths and closed eyes are overwhelmingly powerful and slightly troubling—my voyeurism highlighted by the absence of any returning gaze.

I wonder how people felt watching the mobile phone video of Saddam Hussein’s death. Tikka’s work highlights the ways that mobile media might influence social etiquette and norms, raising questions about how to navigate when mobile technology disturbs the boundary between public and private, and embodied experience becomes disrupted by telepresence. Should we be able to peer this closely at others’ deaths and births? Tikka reported that despite the images being freely given by the mothers, she still felt the need to moderate them for public display.

personal screenings

Most of the films shown came from the likes of the UK’s Pocket Shorts (UK), the Toronto International Film Festival and Amsterdam’s Playmobiel. Australia had a major presence in this program with exhibitions from Australian Network for Art and Technology, dLux Media Arts and Metro Screen. Australia was also represented in the big screen competition with works by Melinda Rackham, Damon Herriman, Michael Lohmaller and Hermione Merry. Merry won third prize for her Sunday or the Circus.