Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/2/208_reid_chamber2.jpg" alt="Simon Meadows, Anna Margolis, Sally Wilson,

Mathew Champion, The Hive”>

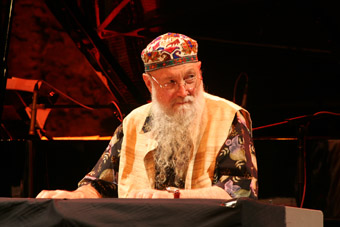

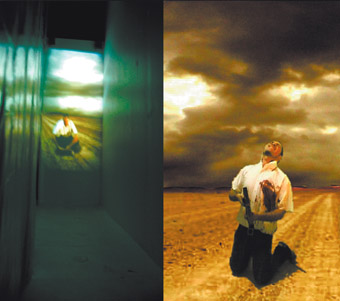

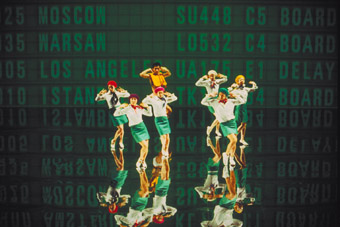

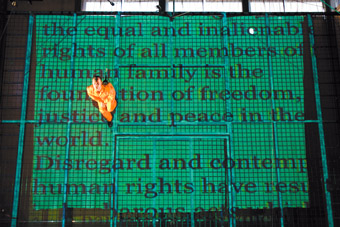

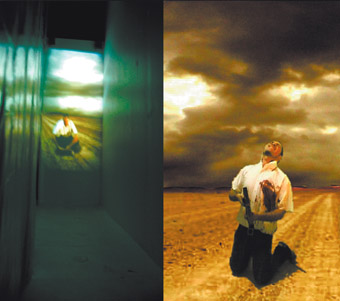

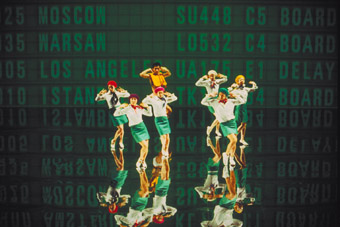

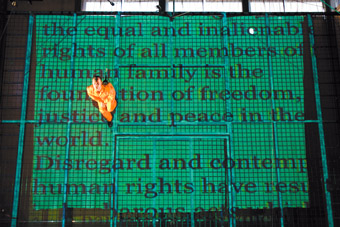

Simon Meadows, Anna Margolis, Sally Wilson,

Mathew Champion, The Hive

photo Ponch Hawkes

Simon Meadows, Anna Margolis, Sally Wilson,

Mathew Champion, The Hive

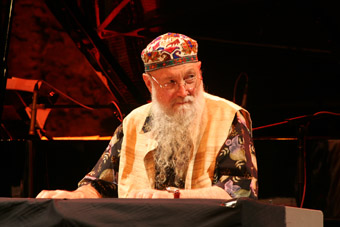

The Hive is an adaptation by Nicholas Vines of Sam Sejavka’s play The Hive about the death in 1915 and posthumous fame of the Bloomsbury Group poet Rupert Brooke. The 1990 play was much lauded when it first appeared, winning the Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for Drama. Judging by the libretto for this version, the play is a wordy work, full of sharp exchanges and potent commentary. The opera takes the form of a series of vignettes that capture key moments from the death of the poet during World War I through to World War II, when England was again at war and the memory of Brooke was enlisted to encourage patriotic duty. Sejavka himself declares in the program note that his real concern is with ‘media hype’, the exploitation of the memory of Brooke for political purposes; a lesson that still has much to offer.

Chambermade’s production is for an intimate space–small stage, no wings, simple, well-chosen props–hat focuses on the performers’ delivery of the text. The backdrop is a clear plastic sheet with a green (starboard?) light behind, giving the setting an unworldly feel. The 5 performers, 4 of whom take multiple roles, are elaborately costumed, providing cues to their identities and the eras in which the action is set. The opera opens with the performers as crew members observing Brooke’s body on board the ship where he died, aged 27, dirging “Rupert Brooke is dead, Rupert Brooke is dead!” and hailing him as a fallen hero. “He died for his country”, they cry, mourning not only his demise but also the manner of it: “an insect bite, what a meagre end…” The blood poisoning induced by a mosquito bite was sometimes downplayed in the publicity surrounding his death. His so-called war sonnets were championed, and Winston Churchill in particular wrote an obituary that offered Brooke as a patriotic inspiration. At regular intervals the deceased rises from his gurney to soliloquise, at one point intoning: “I am a dead man but I suspect I have more living to do in the minds of men and nations.”

We meet publishers discussing the release of Brooke’s private papers, the executors of his estate, his friends and former lovers, including Bloomsbury Group members conducting a séance to try to contact his spirit. Insects permeate the work; Brooke was fascinated by them, hence the irony of his death, hence the opera’s title. Characters entering the drama create a kind of hive of activity around his memory.

In contrast to much other opera, The Hive is cerebral, discursive and philosophical rather than romantic or dramatic. Passages of involved discussion are periodically interrupted by Brooke rising and abruptly clapping his hands (as if killing an insect), slapping a book, declaring his observations. In the séance scene, the performers chorus, “Thank you, friend, thank you, friend!” while pondering his life, deeds and misdeeds. They query his sexuality, “Does he prefer man or woman?” and “Did he take Virginia?” Woolf rejects these claims with a melancholy reply, “Spirits can lie like the rest of us.” They analyse his poetry, his former lover Noel wailing. “Rupert, you confuse love with lust.” Those exploiting and judging him reveal themselves.

Vines’ score is fresh, lyrical and suitably edgy, ably supporting the unfolding dialogue. Using just two keyboard players, on synthesisers and a piano, his music is eclectic, flavoured with Romantic and contemporary styles to characterise particular moments. Well-known musical forms—a piece for organ at Brooke’s funeral and later the piano accompanied by a synthesised/sampled sound of a cello in salon style—build atmosphere. Douglas Horton’s direction emphasises the text and its interplay with the score. The actors’ movements on stage are economical, focussing attention instead on the aural elements. Baritone Simon Meadows creates a strong, introspective Brooke who is engaged, through an ongoing dialogue with his various acolytes, in an analysis of self and the world. As an opera, The Hive is a work with great potential, though sung lyrics can be difficult to interpret making the nuances of the text, and even the narrative itself, somewhat elusive.

Chambermade, The Hive, writer Sam Sejavka, composer Nicholas Vines, director Douglas Horton, performers Ben Logan, Sally Wilson, Anna Margolis, Simon Meadows, Arts House, Meat Market, Melbourne, Aug 23-Sept 10

RealTime issue #75 Oct-Nov 2006 pg.

© Chris Reid; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

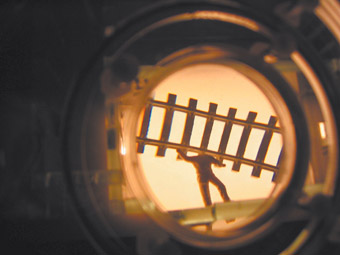

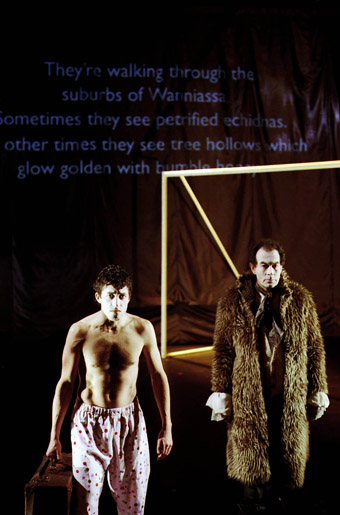

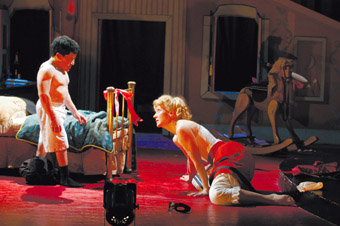

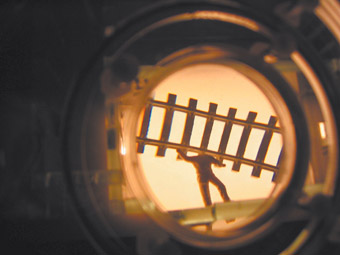

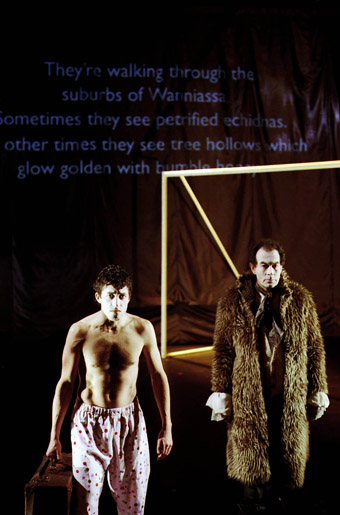

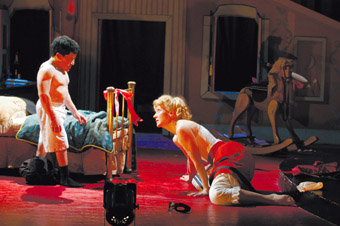

Einstein on the Beach Part 1 & 2, (Leigh Warren) design Mary Moore

photo Tony Lewis

Einstein on the Beach Part 1 & 2, (Leigh Warren) design Mary Moore

There’s a sour adage coined by George Bernard Shaw many educators would be familiar with: “He who can, does. He who cannot, teaches.”

It’s a nasty jibe and one that is roundly repudiated by the professional lives of theatre practitioners currently teaching in Australia’s tertiary education sector who retain a commitment to working in the performing arts while mentoring the next wave of directors, actors, animateurs and designers.

Richard Murphet, VCA

For almost all his working life, Richard Murphet, Head of the Theatre Making Department at the Victorian College of the Arts, has combined his work as director and writer with teaching. He has reached a point where, while a permanent employee of the VCA, he can negotiate regular time off in blocks to work on his own projects. This is necessary, he says, because “I’m pretty obsessive, so if I’ve got a group of students, I get completely involved with their work. So it’s not just time, it’s emotional time as well—just getting your head clear.”

He won’t be taking time off from the VCA this year, but he’ll be relieved from teaching duties to act as artistic director and mentor for a project with DasArts, the Dutch performing arts training academy (RT68, p42). The scale of the work is daunting: 24 young artists from VCA and DasArts will travel to North Queensland where, 400 years ago, the Dutch first made landfall in Australia. The students and their mentors will stay with 3 Aboriginal communities in Cape York, before returning to Melbourne. The task is then to create a work based on their research and experiences to be performed as part of the Melbourne International Arts Festival. Murphet likens the process to the Dutch explorers’ voyage all those years ago: crossing vast expanses of unknown seas, not knowing what awaits at journey’s end.

It’s the type of undertaking that being part of an educational institution can sometimes provide. Initiated by the VCA, the project, according to Murphet, demonstrates the commitment the institution has to educators who not only teach the arts, but do the arts. Teaching has provided Murphet with other networks and opportunities. In 1996 he received a National Teaching Fellowship allowing him to travel and establish enduring connections with fellow practitioners in Belgium and Holland. It was also through his work at VCA that he met one of his most crucial collaborators, Lisa Shelton, who was formerly head of movement there.

Mary Moore, Flinders University

Mary Moore, an established theatre designer who teaches in the directing course at Flinders University Drama Centre, has also found herself working on large projects with her institution’s support. Commissioned to produce Memory Museum (RT46, p37), for the Centenary of Federation, she asked the Drama Centre to be a partner in the project. Moore believes the project wouldn’t have been possible without the support from the university. Because of the “immense educational value” of the project due to its experimental nature, the university was willing to allow staff and students to participate.

Moore finds little conflict between her roles as teacher and artist; in fact they complement each other. “I always try and find ways in which [students] can access the industry.” If there are clashes between classes and a rehearsal she has to attend, she will often invite her students along to observe. This provides a definite benefit for her students she believes, giving them an insight into the industry from an insider’s perspective.

Tim Maddock, University of Wollongong

Tim Maddock is busy. He’s formerly from Adelaide where he played a key role in the 1990s theatre scene with Brink (including co-directing a wonderful account of Howard Barker’s The Ecstatic Bible for the 2000 Adelaide Festival). While a relatively new appointment to the position of Performance Coordinator at the University of Wollongong’s School of Music and Drama, he’s also currently immersed in pre-production for The Hanging of Jean Lee (RT 73, p34), a new music theatre work by Andrée Greenwell for The Studio, Sydney Opera House. “It’s proving to be a challenge to manage the time,” he admits, “and I suppose I’m reliant on the university having a flexible enough structure and valuing the notion that I maintain a professional identity in order to be able to continue working as a professional practitioner.”

His involvement in Greenwell’s project came as a result of his role at the university. Greenwell delivered a lecture and had gone on to mentor on a project in the Music and Drama School. Their discussions led to Greenwell inviting Maddock to direct The Hanging of Jean Lee.

Maddock came to teaching through a change in his personal circumstances—he’d had a child and could no longer be quite so casual about earning money. However, a regular income was only part of the attraction: “The proportion of my work being done in universities was increasing…I was supervising productions of plays by Sarah Kane and Martin Crimp and all this interesting stuff and thinking this scope of work and experimentation and creativity going on in the universities feels more alive and more engaged than a lot of the professional practice.”

Helmut Bakaitis, NIDA

Big projects outside the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) aren’t possible for Helmut Bakaitis, Head of the directing school there. Although impressive in Max Lyandvert’s production of My Head was a Sledgehammer in 2001, his commitments mostly limit him to “fairly small cameo roles in the odd movie and television series.” This has meant that his work as a writer has suffered. His drawer, he says, is full of unfinished scripts that he is determined to complete. “My dream is to retire one day quite soon and put down all the ideas in my head on paper or on the computer.” Not that he would want to give up teaching completely. Bakaitis has had a long involvement in youth theatre and continues to be inspired and invigorated by contact with young artists.

Teaching, he says, has helped him develop his skills, particularly as a director and a writer: “I think I was a bit of a touchy-feely type of person and now I’m much more able to be diagnostic and clear in what I want to achieve in conjunction with the artist, which is a skill that I’ve honed through teaching here…Dramaturgy was one of the skills I came with and I’ve continued to develop that through the playwrights’ studio.”

Angela Punch-McGregor, WAAPA

Angela Punch-McGregor was appointed to the role of lecturer in acting at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA) at the beginning of this year. She has also taught at most of the other major performing arts institutions in Australia. While well known for her acting work in film and theatre, teaching and directing are her primary focus these days.

She values the support she has from WAAPA, who have a commitment to providing their students with educators who have a profile and standing in the industry. Punch-McGregor describes the interaction with her students as “joyous.” She is also looking forward to the connections and networking that will be available to her as part of what she sees as a global network of institutions teaching the performing arts. South-east Asia, especially, she believes, will provide opportunities for teachers and artists alike given the establishment of European-style performing arts schools in cities such as Hong Kong.

Interplay of roles

For all the interviewees, there was a significant interplay between their dual roles of artist and educator. For Maddock, teaching has made him more “compassionate” as a director as well as forcing him to clarify his communication methods. This is echoed by both Bakaitis and Moore, who, unprompted, also voice the view that teaching has clarified not only the way they communicate, but also their ideas. Bakaitis and Moore also derive tremendous inspiration from contact with their students.

Punch-McGregor finds the roles of teaching and directing are intertwined. As a director she is concerned with “what is going be to visually and audibly most effective…At the same time, if I’m not getting what I want, I have to instruct in order to get that from the performer.”

For Murphet, teaching and creating his own work provide a kind of balance: “I’ve always found they really feed one another fantastically. When I get worn out—just hitting my head against the problems of putting work out—it’s good to go back to teaching. And when I get drained from teaching, it’s good to go out and do my own work.” His students also reap the benefit of having artist-educators by getting an accurate picture of the realities of being an artist. Murphet says, “Every time I go to direct a play…I don’t know how to do it. I start at the beginning and I ask, ‘What’s directing about?’ and then I gradually find it. And that’s fantastic for (the students), because they feel they know nothing and that’s the state you have to be in when you’re doing art.”

Benefits for students

And what else do students gain from having artist-educators? According to Maddock it’s having teachers whose theatre practice is fresh and alive: “I think when you stop doing it, you calcify and your ideas about doing theatre become frozen in time.”

Bakaitis’ view is that it is crucial that performing arts students have educators who are also working in the industry: “All you’ve really got to offer the students is your address book and your contacts and if you can’t give them current contacts, then what’s the point?” Murphet also acknowledges the benefits for students if teachers can plug them into networks, but thinks it’s of greater importance to infuse them with the excitement of constantly interrogating theatre as a form.

For love or money?

Money is always an issue for an artist trying to survive by their art alone, but none of the interviewees would give up teaching completely if project funding came flooding in. Mary Moore, particularly, relishes her working environment: “This particular relationship [with the Drama Centre] is very special…It’s not really about the hours or the remuneration or any of those things. It’s like a company.”

Both Murphet and Bakaitis say they would like more time for their own work but they would grieve the loss of contact with bright, artistically ambitious young artists if they left their positions. Maddock, too, appreciates the university environment’s vitality and the openness to experimentation. For Punch-McGregor, money has simply never been a reason for choosing any particular path: “I regard it as a privilege to work in this industry.” These committed artist-teachers are nurturing students as colleagues, future collaborators and fellow travellers.

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 2

© Mary Rose Cuskelly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

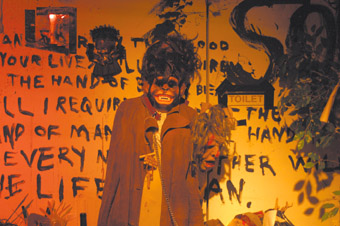

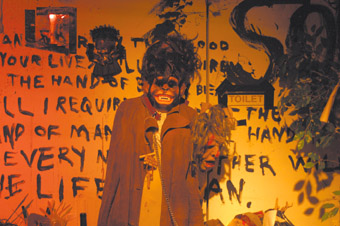

Mark Minchinton

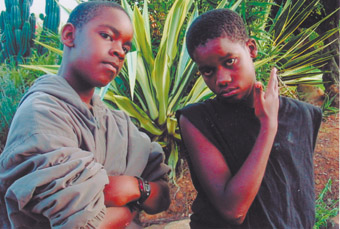

This journey begins with my awakening to my Indigenous identity. This awakening has taken more than 40 years.

The awakening is performed…I walk from the place now known as Busselton—where my grandmother was known as black—to Kellerberrin—where my grandmother was known as white. I carry a pack with food, clothes and shelter. I also carry a digital camera, a handheld computer, a Global Positioning System (GPS) and a mobile phone. A modern nomad.

Mark Minchinton

Twice a day I stop, take a GPS reading and 5 photographs and write about what I hear, touch, see, smell, taste, find, feel, think or imagine at the place I have stopped. Each day, I choose 2 of these photographs and send them with a text to a website.

After teaching performance full-time for many years at Victoria University, performer Mark Minchinton went half-time for 2 years working towards a 3 month artist-in-residency in 2003 at Edith Cowan University in Western Australia.

Minchinton spent lots of time mulling over his venture, one “with a number of agendas, personal, artistic and institutional.” Void: Kellerberrin Walking was a 6-week walking performance from Busselton, in the southwest, to Perth and then Kellerberrin via Wyalkatchem. The total distance traversed was “some 500-700 kilometres—there was lots of wandering!” Throughout the trip Minchinton wrote about what he was seeing and feeling and encountering, and relayed it to his online audience.

On the technical front he had to work out how to keep a growing audience (including many overseas) informed using a mobile phone as the tool for an early example of “the roving blog.” He hadn’t realised that every 3 days or so he could have stopped at small towns linked by a community Internet service, but his own way allowed him to transmit 2-3 times a day.

The experience was “fantastic, much better than sitting in university meetings…and I was paid to do it!” Minchinton discovered, among other things, that “humans are meant to walk long distances—and sleep in the middle of the day.” He slept incredibly well, a revelation for a life-long insomniac. Walking 6-10am was followed by camping and hammock sleeping and then walking again from 4-7pm.

For the first time Minchinton felt he was “bringing together concerns about my own identity and a political program I believed in…a fusion of the personal, the political and the artistic.” He revelled in the “everydayness” of a performance that coincided with his turning away from teaching undergraduates after many years. At almost 50 years of age not only did he feel jaded (“teaching the young is fine, but did they like being with me?”), but also he had a son almost his students’ age (“I get this stuff at home!”).

The experience of the 6-week performance confirmed more than ever Minchinton’s passionate advice to his students: “Forget worrying about form; deal with something that has real meaning for you. That will determine the form.” He likes walking in itself and as a form, and has another big adventure in mind.

Critically, Minchinton’s WA walking took him close to his Australian Aboriginal heritage, something that had been kept hidden in his family. The preparation for the venture, from 2000 on, had involved intensive research into his family history and determined that the performance would be in Western Australia, originally his family’s home.

Minchinton subsequently moved into half-time postgraduate teaching in performance and half time as Director of Moondani Balluk (“embrace people” in the language of Victoria’s Wurrundjerri nation), Victoria University’s Indigenous Academic Unit. Being one of the few senior staff in the university of Aboriginal descent, Minchinton says he leant his weight to such initiatives.

As for being an artist in a university, Minchinton thinks it’s an issue of how much you implicate yourself in university practices and how much you set yourself apart. It’s important, he thinks, to “work with colleagues to turn around expectations”, to assert for example that artistic practice in the university is research. “We teach artists and they do postgraduate work and we take their money, so we have to recognise what they do, and the university needs to recognise that its staff need to do artistic research.”

Above all Mark Minchinton sees teaching as playful and performance as “an embodied ethics.” Whether his own discoveries as he “tramped through landscapes known and unknown” or his students’ everyday encounters, “it’s a matter of observing and absorbing, of how you approach an Other, how you depart, how you make decisions. I don’t care if the student is going into television, performance art or real estate, at least they have a grounding in the understanding of others.”

Mark Minchinton, performance maker, is an Associate Professor at Victoria University and Foundation Director, Moondani Balluk Indigenous Academic Unit.

Although the online version of Void is no longer available, the background to the journey appears on a number of websites including: www.newint.org/issue364/born.htm

–

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 4

© Keith Gallasch; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

At the core of the 200-year old conservatoire culture is the aim of training a musician for a dedicated career as soloist or orchestral player. Because this is an unsustainable goal, behind it lurks the real prospect of a sense of personal failure for music graduates, many of whom have been forced to undertake what they have been led to believe is a lesser career as a music educator, or give up music altogether for some other pursuit. In the last few decades, the rhetoric about music careers has been slowly changing. There is a growing recognition that a typical music graduate is unlikely to have a career which is focused entirely on professional performance in elite musical contexts.

Educators now talk about “portfolio careers.” For music graduates and un-credentialed musicians with strong industry profiles, teaching part-time at a tertiary music school is an attractive element of a portfolio career. But what of practising musicians who pursue full-time permanent employment in a tertiary music school? How do they cope with the demands of a dual career? To find out I spoke to 4 composer/performers who hold permanent jobs in tertiary music schools about the benefits and challenges of this career choice.

Robert Davidson, QUT Creative Industries

Robert Davidson’s Brisbane-based ensemble, Topology, is the major vehicle for the dissemination of his works, although he has written for other combinations. Based at Queensland University of Technology’s Faculty of Creative Industries, he came to academia after years of believing it would not combine well with his career as a practising musician, a belief based on his experience of American musicians such as Steve Reich who adamantly avoided academia. He changed his mind after realising that many Australian composers he admired were full-time academics, and concluded that university teaching would feed into his arts practice better than the computer programming he was doing to supplement his income.

Jim Kelly, Southern Cross University

In the 1970s and 1980s jazz guitarist Jim Kelly had a lucrative career as a session musician in Sydney playing all styles of contemporary music. As popular music became more electronic he decided it was time to revive his live performance career. In the meantime, however, the cost of living had gone up but gig fees had stagnated, so as an additional source of income he turned to private teaching. Kelly found he had a knack for communicating his ideas about guitar playing and improvisation, and even wrote a book on improvising. In the late 1980s he was recruited by the Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education (now Southern Cross University, Lismore, NSW) as a full-time lecturer in its new contemporary music program.

Thomas Reiner, Monash University

Although Thomas Reiner sees himself as primarily a composer, he also has a background in systematic musicology (he has written a book titled Semiotics of Musical Time). Based in Monash University in Victoria, Reiner formed a group, re-sound, a collective of experimental performers and composers, in 1996. From this point his artistic practice shifted more from notated scores towards collaborative structured improvisations that evolved into compositions through workshopping and rehearsal. Reiner admits that his university position provides financial security but adds that his teaching and research have become integral to his creative practice.

Stephen Whittington, University of Adelaide

Stephen Whittington is based at the University of Adelaide but maintains a professional practice as a composer and performer. As a contemporary classical pianist he gives recitals but is also strongly involved in electronic music, installations, multimedia and film. Recently, for example, he performed live soundtracks to 4 films at the 2006 Sydney Film Festival with Ensemble Offspring. Whittington also enjoys the security of an academic position but says if he had to make a choice between teaching and his professional musical practice the latter would win out.

Learning from teaching

All 4 musicians were positive about the benefits of being artist-educators. Robert Davidson teaches a broad range of courses in the small Department of Music and Sound at QUT including world music, musicianship skills, composition, non-linear music for multimedia and cross-cultural music techniques. He commented, “It’s amazing how much you can learn by having to teach something.” This is a common experience amongst academics who are required to teach subjects they may not have any particular expertise in, and thus are forced to engage with the material in an intensive way to be able to explain it coherently and inspire their students. The trade-off for all the hard work is an increased understanding of the technical and aesthetic aspects of genres and techniques that can feed back into the teacher’s own art practice.

Learning from students

Because students come into courses with such varied backgrounds, skills and interests both Whittington and Davidson suggested that they learnt as much or more from their students as the students learnt from them. This was particularly the case with postgraduate composition students who typically come into a program with established professional careers, a significant body of work, and very varied approaches to musical creativity. Reiner suggested that rather than teaching postgraduate composition students about how to compose, his role was helping them “find a way to think of how their work is making an original contribution to knowledge.” This approach, expected for students undertaking creative projects at doctoral level, had filtered into his own approach to composition. As a result of his teaching he felt that his work had become more “grounded in a clear aesthetic outlook.” As an improvising musician, Kelly believes that it is important to “keep aligned with young people” as well as working with musicians of his own age. He cited the case of Miles Davis who kept his music fresh by performing and recording with much younger musicians. Working in a university context has allowed Kelly access to a pool of younger musicians to work with professionally. He is recording a duo guitar album with one of his students, Matt Smith, later this year, and has regularly played with non-guitar students, mostly drummers and vocalists. Whittington, Davidson and Reiner also cited examples of collaborative work with students. Reiner, for example has released Conversations (Move CD), an electroacoustic collaboration with students Steve Adam, Philip Czaplowski, Robin Fox, Russell Goodwin, and Peter Myers.

Inside and out

Access to fellow staff members as collaborators can be another advantage of an academic position. Kelly has regularly worked with all the performers on the Southern Cross staff, including d’volv, a guitar trio creative collaboration with Peter Martin and Jon Fitzgerald. Another example is Davidson’s work with colleague Andy Arthurs on Deep Blue, an ARC Linkage grant partnership between QUT and the Queensland Orchestra. Whittington, however, said he was more likely to collaborate with artists outside the university, especially from other disciplines.

The time challenge

There can be big challenges to maintaining an academic job and an artistic career simultaneously. In the era of diminishing government support for education and demands for increasing levels of accountability, music academics are increasingly involved in higher teaching loads, burdensome administrative responsibilities, expectations to apply for grants and sponsorships and pressure to upgrade their qualifications. Indeed the lack of time to devote to creative work and performance was a common theme explored by all four musicians. Jim Kelly said that although he was able to maintain an active local and national performance schedule it was almost impossible to tour. For example, he had to turn down the opportunity to do a month-long Australian and New Zealand tour with Manhattan Transfer because he knew that the disruption to the teaching program would be too great and that making up the classes when he returned would be exhausting.

For Reiner, the changing conditions of the workplace mean that it is no longer possible, as it was in the past, to put aside a month or 2 to work on a creative project. His solution to create enough time is to get up very early several mornings each week. Both Whittington and Davidson stressed the importance of maintaining a balance between the academic job and artistic activity, neglecting neither and giving full attention to both. This requires careful planning and excellent time management. Davidson believes that a very focused approach to composing and instrumental practice can produce good results in concentrated periods of time.

Research pressure

In addition to artistic output there is also an expectation for artist-educators to produce research outcomes from creative work, even to the extent of having to write research papers about creative work. This can be a challenge for artists who are not used to this way of thinking, and don’t have writing as their primary skill. According to Reiner there is a real danger in the intellectualisation of creativity, a danger that spontaneity will fall by the wayside, and this is often the assessment that the artistic community gives to music created in a university context. Davidson felt that we have to be careful that creative music doesn’t become like science as it has in certain American university contexts. Both Davidson and Whittington believe that a great deal of energy is spent arguing in the university context about the value of creative work as a form of research. There are also significant frustrations involved in the way artistic activities are perceived at the government level. Although, for example, all academic staff in universities are expected to apply for research grants, the Australian Research Council currently does not fund creative or performance activities.

Teacher as role model

The value to the students of having lecturers who are active professionals in the industry was stressed. Davidson emphasised the idea of the role model: that there was no other way to learn to be an artist apart from being around other artists. Whittington felt that “the artist as a teacher sets an example of what is required to be an artist: the dedication, the passion, the desire to communicate, the desire to create.” By involving his students in his professional work, Kelly considered that he was not only teaching his students how music should be played, but also how to behave professionally on the job. Reiner believes that he is able to encourage his students to become more reflective and more self critical about their work, an essential skill for career development.

Despite the frustrations of administrivia and other time-consuming demands of working in an academic environment, the career of the artist-educator appears from my discussions to be a stimulating and rewarding one in the music field. This is not surprising since there is a long tradition of very prominent Australian musicians holding down full-time academic jobs. Two composers (Barry Conyngham and Roger Dean) even became vice-chancellors and continued to be artistically productive.

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 6

© Michael Hannan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

<img src="http://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/2/214_smetanin.jpg" alt="Michael Smetanin, Used with permission,

Sydney Conservatorium of Music”>

Michael Smetanin, Used with permission,

Sydney Conservatorium of Music

photo Steve Keogh

Michael Smetanin, Used with permission,

Sydney Conservatorium of Music

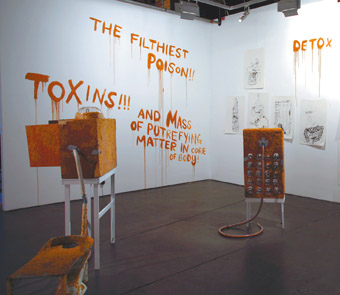

One of Australia’s leading composers, Michael Smetanin, has held since 2002 the Chair of Composition at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, an institution employing a high percentage of artist-educators. Although he had taught part-time since 1988, this is his first full-time teaching role: for most of his career he received commissions and awards so frequently that he was able to devote most of his time to composing. He thus has first hand knowledge of the life of both freelance artist and full-time academic.

Have there been positive results for your composing from teaching?

Sometimes you see the different ways students approach compositional problems. Not that I then do the same myself, but it’s good to see that different angle, it keeps you a little bit sharper. I suppose as you get older you can maybe get a little bit more confident in your own technique, and that might make you feel a little lazy. You can see that happening with a lot of composers, as they get older the music is not as interesting anymore.

No danger of getting in a rut?

Hopefully. I enjoy teaching. I like teaching composition, it’s quite good fun really. It keeps me perhaps more energetic, not as complacent, and it’s fun to be with younger people. And more than anything else it keeps you feeling happy with yourself: it’s not so much that it’s making a direct benefit musically or technically, it’s more psychologically, it keeps you on the ball a little bit more.

Compared with when you were composing full-time, are there advantages to teaching?

For so many years it was a struggle financially. Sometimes it was great, but I had some really tough financial times. So this job is a privilege and a luxury really. Sometimes you get stressed out about the difficulties of the institution and having to deal with a new set of problems, like the lack of funding for tertiary institutions. That takes its place.

I don’t write 3 chamber pieces a year anymore, which is a good thing. In some ways it’s good not to have that necessity to be churning stuff out, because I think you might find artists who, once they’re under the gun and making more so-called art than they really should be, the quality is going to suffer. In a way making a little bit less these days is a good thing because the quality is going to remain high, if not improve. I don’t feel as if I’m slackening off.

Full-time teaching hasn’t impacted negatively on your productivity?

Largely no. I think that if I was to suddenly decide that I want to write 3 chamber pieces a year I’m sure I could. But from time to time I feel that some of the red tape can be a little bit of a nuisance. I think that more of the clerical work is being pushed onto academics.

In the past might it have been easier to produce creative work while holding a position like yours?

Yes, I think that the pressure on how much work an academic actually does has increased little by little for decades. In the early stages of a piece I really like to have consecutive days of peace and not be bothered by niggly bureaucratic stuff.

In semester breaks?

Generally. It’s best to start a piece in a break. I work better if I have a good number of days together, consecutively. It’s not so bad when I’m getting towards the end of a piece, I can pick it up coming home at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. But I don’t like working at night. When I am further into a piece I can work on a bit longer because I already know it. Most composers will probably tell you that they write the last few minutes of their piece much quicker than they wrote the first few minutes. So it depends on which stage I’m at with a project as to how fast I’m working and how easily I can walk into the studio and pick up on it.

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 8

© Rachel Campbell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

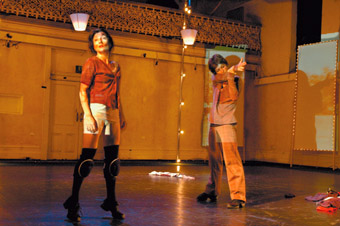

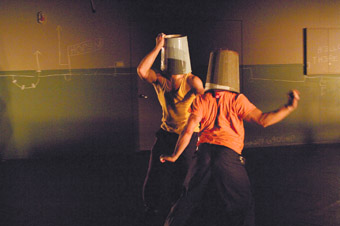

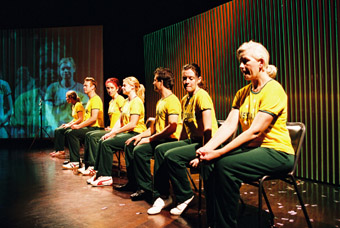

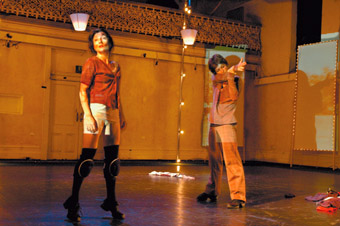

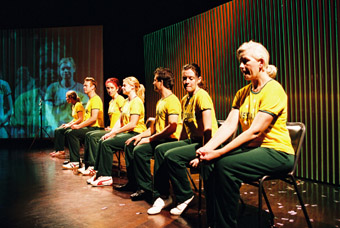

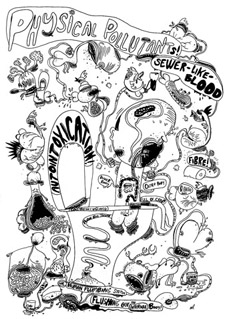

Alistair Riddell, Belinda Jessup, Lucie Verhelst, FyberMotion (2005)

photo Margot Seares

Alistair Riddell, Belinda Jessup, Lucie Verhelst, FyberMotion (2005)

As sound is a small but growing culture it is not surprising that a significant number of the leading practitioners across the country are also the key educators. The increased interest in sound practice over the last 5-10 years is directly reflected in a developing range of courses offered through art schools, conservatoriums and arts faculties. This article surveys 6 key artists who continue to play a significant role in educating the next generation of sound artists and explores the tensions and pleasures of balancing an evolving practice and educational responsibilities.

Dr Alistair Riddell, ANU

Alistair Riddell is Lecturer in Computer Music, Centre for New Media Arts (CNMA), Australian National University (ANU). He started his full-time teaching at ANU in 2002 after working intermittently in Melbourne and the USA.

“The roles of educator and artist embrace an interplay made up of many subtle components: concepts, knowledge, experience, creativity, aspiration, inspiration and pedagogical expectations. I’d like to think that teaching benefited my practice but I think it is more in terms of being in a positive position with respect to the arts. You want to feel that when you teach or simply communicate, you inspire.”

When asked how he balances personal practice and teaching Riddell replies, “The bureaucratic and teaching demands of academia are ever present. To at least attempt to ameliorate this situation I can teach what I practice and vice versa. That is certainly the mantra of ANU. However, the trick is to keep the pedagogy current and relevant…Teaching does clarify certain aspects of practice. There is nothing like teaching something in order to really learn it. You have to know what you are talking/thinking about much more than you might just by practicing it.”

It appears that the pivotal point for Riddell is the nature of the interaction with the students: “Educators need to be able to remove themselves from a discussion with students up to a point and just listen to how the student expresses their ideas and concepts…I am very dependent on students providing me with feedback on contemporary aesthetics, events and technology. I actively cultivate a bilateral exchange of information on an informal basis and attempt to organise, support or participate in student events if and when the opportunity arises.”

Philip Samartzis, RMIT

Now Senior Lecturer & Coordinator of Sound, School of Art, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT), Philip Samartzis’ role gradually evolved from being an AV technician at the Phillip Institute, while studying Media Arts, into teaching. He believes this allowed him to “look at issues from both sides to implement the most effective strategies, to resolve problems…Although I had aspirations to teach formally I felt I lacked the experience to offer students the broad perspective that would benefit them. However as I moved from undergraduate to postgraduate study I was offered more and more casual teaching until a full-time position became available in the Media Arts Program at RMIT.

“I have always considered myself an artist first”, declares Samartzis, “and an educator second…(T)he experience I have accumulated as an artist provides direct and longstanding benefits to my students. I often draw upon my own experiences to illustrate real world situations that are likely to confront students at different stages of their careers, such as how to secure cultural support, or how to develop publication and exhibition opportunities. However teaching has had a profound effect on my art practice. It regularly makes me question the choices that I make in the development and execution of a project, and to consider the benefits that can be derived from my work beyond my own personal aspirations.”

Like Riddell, Samartzis sees the interaction with the students as key to the productive interplay of artist and educator. “Teaching allows me to test ideas upon students in order to gauge reactions, and affords the opportunity to explain concepts and/or methodologies within a critical culture centred on robust debate.”

On the issue of balancing academia and practice Samartzis is positive: “I actually enjoy splitting my time between teaching and artistic commitments. I like the social discourse and academic rigour that the university provides, whilst simultaneously enjoying the time and support I receive for professional development.”

Cat Hope, WAAPA, ECU

Lecturer in Music (Composition), Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts (WAAPA), Edith Cowan University, Cat Hope is a relative newcomer to full-time teaching. She has been working for over 10 years as a composer, bass player and more recently as a multimedia artist. She was invited to teach at WAAPA 2 years ago after conducting several guest lectures.

Hope sees the interplay of roles as “complex, intertwined and probably very personal…[which] is changing now with the introduction of the RQF [Research Quality Framework]. Fortunately I teach at a university that rewards artistic practice as it would research in more classic academic areas…but I think if you are passionate about a subject, students pick up on it with a similar enthusiasm and that makes it better for everyone.

“Teaching inspires my practice in that it provides facilities and access to performers that I could have only dreamt of before. I often come across interesting material while researching lectures or [finding] a focus for a student, and that leads to something new for me…Being back at university has made me look more into music, whereas I was heading in a multimedia direction…I’ve really got into research, it’s the part of university life I relate to most. I was doing a lot of that as an independent artist but now I get paid for it.”

In terms of balancing the demands of academia and creative practice Hope says, “You must make time somehow to allow yourself to grow and change…The research day for academics is becoming a thing of the past, which is a shame because that provides an invaluable window for artists.” In order to sustain her practice Hope also began a PhD in Sound at RMIT when she commenced full-time teaching.

Andrew Brown, QUT Creative Industries

Andrew Brown, Senior Lecturer, Music & Sound, Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, turned to teaching quite quickly. “I had a teaching qualification and decided to use it after realising that touring in rock bands was not an attractive long-term option.

“It is important that teachers maintain an active artistic life, as this keeps them grounded in the experience of practice and the enjoyment of the art. It also helps keep them up to date with trends and changes in the field. It is also useful for artists to teach, because it requires them to reflect on and articulate ideas and techniques. This provides an additional clarity to practice and often assists in an artistic development with greater intention. Keeping connected to young people enthusiastic about music is also continually uplifting.”

To balance practice and teaching Brown tries “to blend them where possible so they don’t seem like separate activities. For example, performing as well as presenting papers at conferences, developing tutorial materials as a way of consolidating my own understanding, working collaboratively with students on artistic projects, and shifting teaching activities toward my evolving artistic interests.”

Garth Paine, UWS

Garth Paine is Senior Lecturer in Music Technology, School of Communication Arts, University of Western Sydney. He turned to teaching full-time in 2002 after a 16-year career working in theatre, dance and museums with his company Activated Space. “Academia seemed like an option that allowed me to offer something from my years of experience whilst continuing to grow creatively.”

Paine sees that the emphasis on research is one of the benefits of working within academia. “Creative practice is central to all my teaching and, within that, exploration, innovation and discovery are paramount. This approach makes the praxis between research/practice and teaching a real and vulnerable one. It’s where students are exposed to the nature of both the practice-based and industry research I undertake and how that informs both my own practice, my passion for experimental sound, and the framework in which I position my teaching.

“Maintaining a balance is very difficult. I have used ARC funding mechanisms and industry partnerships to grow my research workload in areas that are important to my practice, hence making more space for artistically relevant research within the academy. However, most of my composing and performing is done in my own time outside the academy, even though this is, to some extent, quantifiable as research.”

Julian Knowles, University of Wollongong

Prior to working in universities, Julian Knowles, Head of the School of Music & Drama, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, worked in post-production as a freelancer and for the ABC, spent time in England with the indie band Even as we Speak and was active in the electronic/experimental scene. In 1993 he was approached by Michael Atherton to consult on a new course being developed at the University of Western Sydney and was soon after appointed as a foundation staff member of a “contemporary focused music degree.” Eventually he became Head of the School of Contemporary Arts. In 2005 he moved to the University of Wollongong. He declares, “I can honestly say it was never my intention to teach…I probably landed one of only a handful of jobs in the country which provided scope to explore my musical interests in a contemporary focused department.

“I am a strong believer that those who teach should be actively engaged in practice themselves. This positions you at the centre of new developments and stops you from becoming out-of-touch…In order to educate professionals, you need to understand the details and dynamic of professional life…It is often said that Generation Y need convincing of the authenticity of a source of knowledge, therefore it helps in this regard.

“Whilst I hate the idea of teaching as a cloning program, I do bring fresh ideas from practice into the teaching context at a fairly swift pace. In this sense, my students become part of my own enquiry into where practice is heading. This conversation keeps us all interested in what we are doing.”

Knowles points out “working for an academic institution places a range of demands on you, so the ‘educator’ these days is also an administrator, manager, researcher, curriculum designer, community/industry links broker and so on.” In order to find some balance he has “taken some radical steps in the past, including moving a step or 2 down the institutional hierarchy in order to regain some space to be a balanced practitioner/teacher/manager as opposed to a manager. I’m embarrassed to admit I have only had one bout of study leave since 1994. I have spent a lot of my career in a climate of shrinking budgets and radical organisational change.” However he is keen to point out that the issue of balance is just as present outside the institution “given the state of funding in the small to medium arts sector.”

Good teacher, better artist?

Clearly my interviewees think that maintaining a practice as an artist has a very positive effect on their teaching. But in the long run, is teaching integral to their practice and do they feel it makes them better artists?

For Cat Hope, the answer is no. “There are opportunities at university that could benefit me as an artist (equipment, networks, research materials and funds), but that could never make you a ‘better artist.’ A wage could never make someone a better artist, but it may help him or her to create and experiment. And what better way to make a wage than working in an area you love?”

Andrew Brown believes that teaching is certainly influential but not integral to being an artist. “I think that if I were wholly devoted to being an artist I may be a better artist than I am. Being a good educator is also rewarding but time consuming…I would certainly be a different artist if I was not an educator because educational interests and interaction with students have influenced the direction of my creative practice (as have my interaction with others artists and other art forms).”

Philip Samartzis differs: “I don’t think I could operate as effectively as an artist without the academic community from which I have drawn much of my inspiration over such a long period of time. However in order for both my academic and creative aspirations to grow I sometimes need to escape the university environment to focus on my art practice for concentrated periods…Teaching is an integral part of my practice and I will continue to do it as long as I have the flexibility to move between my various academic and artistic commitments and interests.”

Garth Paine feels that working within the academy “allows me to be more conscious of my artistic development as research, and to make time and space for that maturation…The goal of working within the academy must be for it to serve both the artist/educator and students—for the praxis to enrich both parties.”

Julian Knowles thinks the roles of teacher and artist must be integrated: “Whilst universities function as de facto patrons of arts practice through the allocation of an unfunded research load, I am not comfortable with the idea of the university as a simple financial crutch. ‘Teaching as survival’ therefore does not appeal to me…I see it as a choice to work inside the academy and I find it stimulating to be part of a learning/research community. Teaching to me is about giving something back and interacting with young/emerging artists.”

Alistair Riddell muses, “I don’t think I could say that I’m a better artist for teaching. I might be a better person, whatever that means, but I’m not sure I could say that either…Perhaps, more than anything it is a process of living, a state of being lucid and exchanging with others a dynamic for living, a past for a present.”

Cat Hope is currently in Singapore on an Asialink residency at Theatreworks. Philip Samartzis will present Immersion 4, improvised live collaborations between Australian and German artists at Interface: Festival of Music and Related Arts, Berlin Sept 14-Oct 6. Andrew Brown’s current projects include building generative music software for children, in particular jam2jam software, http://explodingart.com, and live coding performances, http://runtime.ci.qut.edu.au/pivot/entry.php?id=8#body. Garth Paine, in collaboration with Michael Atherton, will be releasing the Parallel Lines CD through Celestial Harmonies later in 2006, and his Meterosonics project can be viewed at http://www.meterosonics.com. Julian Knowles, in collaboration with Donna Hewitt will perform at the 2006 International Computer Music Conference in New Orleans, USA November 6-11. His sound design can also be heard for Michael Riley’s Poison (1991) exhibited in Sights Unseen, National Gallery of Australia until Oct 22. Alistair Riddell is presenting FyberMotion, an installation in collaboration with textile artists Belinda Jessup and Lucie Verhelst, Aug 1-11, Belconnen Gallery, Canberra.

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 10

© Gail Priest; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

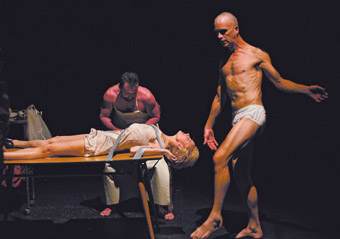

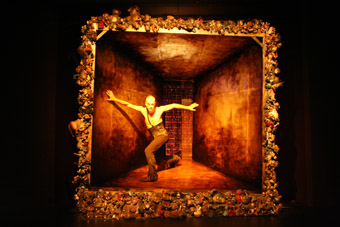

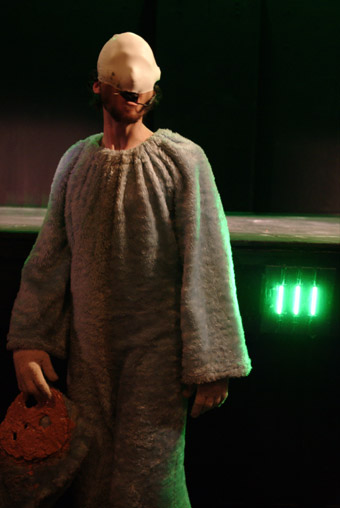

Cheryl Stock, Accented Body

photo Hyojung Seo

Cheryl Stock, Accented Body

High profile, practising artists are not employed full-time in dance courses as readily as you may find them in visual arts, music and literature departments. This is partly due to the time-consuming training regimes and maintenance of practice that dancers and choreographers must undertake along with touring commitments that require chunks of time off. It’s also partly due to the stigma attached to ‘educational choreographers’ in this country.

While full-time appointments may be scarce, an abundance of artists supplement their working year with casual teaching in tertiary institutions, which offers practical support, teaching experience and a chance to try out ideas. Bernadette Walong points out that the University of Western Sydney “has provided employment and research-related opportunities to NSW-based and interstate artists such as Kate Champion, Rakini Devi, Julie-Anne Long, Dean Walsh and Kay Armstrong.” Other dance artists who have worked itinerantly in courses around the country include Gavin Webber, Sue Peacock, Tracie Mitchell, Sue Healey, Claudia Alessi and Chrissie Parrott.

Four professional dance artists working in universities offer their views on the relationship between practising their art and teaching, how the university benefits their practice, and how students and institutions benefit from artists.

Bernadette Walong, University of Western Sydney

Bernadette Walong is a choreographer, performer and consultant on dance and education. She has worked with Bangarra, Meryl Tankard, Dance North and the Australian Ballet, and has created dance films in collaboration with Michelle Mahrer and Richard James Allen. Walong has been an Associate Lecturer in Performance at the University of Western Sydney since 1999 and is one of 2 dance staff there.

I teach at UWS on a part-time basis. This allows me a certain amount of flexibility to accommodate my work as a practitioner. Annual leave is dedicated to any international activities. In the past, and prior to the current workplace agreements, larger blocks of time away were easier to negotiate with the option of making up time lost by working additional hours/days.

My role as an educator impacts on my practice and vice-versa. The 2 contexts involve different playing grounds, but they emerge from the same foundations. Of course my expectations of a student are not entirely the same as those of a professional. I like to call them “professional students.”

Teaching has definitely strengthened the facilitation skills I bring into my practice. My communication and inter-personal skills have benefited as I am forced to be clear in my approach. And I am more conscious of the value of the individual—it expands the possibilities within a creative situation because I am able to entertain a much wider variety of perspectives.

As an independent artist I have been extremely lucky to manage part-time work and my practice. Tertiary dance courses fill the gap that our lagging industry has created for independent artists. Working in this environment has also enabled me to refine my choreographic practice and research both conceptually and physically as I can play/experiment with ideas over longer periods of time.

The benefits that UWS gain are mainly through connections to industry practice. Being employed part-time means I am continuously updating information relating to the field of practice as passed on to students. Secondly, students who have applied to the course have been aware of my work as a choreographer/performer prior and external to UWS—many students had studied Ochres (co-choreographed for Bangarra) as part of the HSC dance curriculum. This influenced their choice of institution.

I can genuinely say that students want to believe that they are getting the real deal, that is, learning from people they know have a professional track record. Learning from practicing artists—living and breathing, not simply documented in a textbook—means they have a direct connection with their field of study. This is a valuable and important tool for tertiary institutions because education should not be isolated from practice. The issue is research and creative learning, as opposed to the institutional trap of regurgitated knowledge.

Judith Walton, Victoria University

Judith Walton is a Senior Lecturer in Dance at the Department of Human Movement, Recreation and Performance, Victoria University. She is one of 5 staff in Performance. Her recent works include no hope no reason, a multimedia performance as part of the 2004 Melbourne International Arts Festival, Lie of the Land, a Gateway commission in Adelaide with visual artist Aleks Danko, and Project Eudemonia, a series of interventions with Rachel Fensham for the PSi10 (Performance Studies International) conference in Singapore in 2004.

In recent times I have taken leave without pay in the need for artistic autonomy—to be independent of the institution and its rapid transformation into a business. This has been my ‘strategy of freedom’ that François Deck articulates: a way of removing myself from the economic function of the institution (in Brian Holmes’ Artistic Autonomy and the Communication Society).

I don’t divide myself, only the time I spend on different activities. Everything that I have gleaned from making and performing is available when I teach and vice versa, and the whole of my life experience obviously informs both activities.

I perceive my art practice as separate from the university that has, nevertheless, supported it financially through my wage. That is, my job has indirectly funded my art practice. There is a general awareness of the growing control exerted by the institution on artistic and cultural production and the very real danger that art making can become harnessed to function, productivity, economic viability, and used as a justification for the institution’s claim to the fostering of a civic society. In a small and perhaps inconsequential way the removal of my art practice from the institution is a resistance to the dominant urge for art consumption, and a conscious reclaiming of the self-governing, playful, open, unknowable, experimental situation that, for me, art making requires.

In short, there is an incompatibility between the making of art and the ideology of the university. In my role as an art educator, these concerns form part of a continual critical debate that informs my strategies and tactics for maintaining an environment conducive to art education.

Performance is understood through the thinking and practice of performing. Art education should set up systems of inquiry to precipitate the making of art. This encompasses the identification and creation of theories, discourses and practices that enliven, extend, question, interrupt, disseminate, challenge, confirm, fail, reinvent, and disturb the making of art. A fundamental principle of Performance Studies at Victoria University is the involvement of practising artists in the teaching of performance.

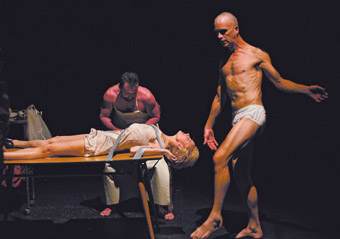

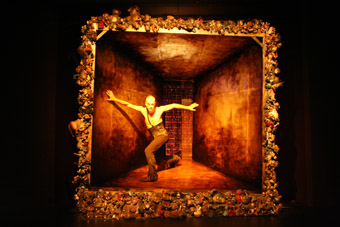

Cheryl Stock, QUT Creative Industries

Cheryl Stock is Associate Professor of Dance at Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology (QUT). She has had a successful career as a choreographer and academic and was a founding member of Dance North in Townsville, Queensland. Her most recent work, Accented Body, is presented as part of the 2006 Brisbane Festival.

I guess I’m really an all or nothing person, so for me to do my practice as I want to, I do it very rarely. With Accented Body, I was given 4 months professional development leave. The preparation had to happen outside of that of course. But teaching and creative practice are actually really integrated for me. For example, I draw on my skills as an artist and as an academic in working with the research students. But it is hard to do your own practice, especially as head of department.

With Accented Body I have had access to the most amazing technology through the institution and have been able to bring in international artists. It is a cutting edge project and this is due, in large part, to the facilities offered by the university and my exposure to the work of artists and staff in other fields here. That exposure has actually shaped the project into what it has become. So I don’t mind spending all of my time being Head of Dance if once every 5-7 years I can do a project like this, which wouldn’t be possible without the institution.

Because of the focus on practice as research at QUT, and given my experience in the professional field of dance, I have taken on a role facilitating the work of other artists by encouraging them to take on higher degrees. So I have become more of a creative producer/director—and that applies to the Accented Body project as well—drawing together staff, students and artists across a variety of fields of practice.

It’s important for the students to know that the people they are working with do have a practice… They are very nurtured in this tertiary institution. They are supported by postgraduates who come in and tell them about ‘the real world’ and show them by being role models. And we support those artists through their research at QUT. If we didn’t have that nexus our course would be irrelevant.

Michael Whaites, WAAPA

Michael Whaites is a choreographer and performer who has had an impressive career working with choreographers such as Twyla Tharp and Pina Bausch. He returned to Sydney in the late 1990s and has pursued a career as an independent choreographer and dancer. This year, Whaites became Lecturer in Contemporary Dance at the West Australian Academy of Performing Arts and Artistic Director of LINK, WAAPA’s graduate dance company.

Three quarters of my time is spent with teaching and administration. At this early stage teaching and working full-time at a training institution (6 months into the job), I am finding that dividing my time between teaching, organizing the company and being creative is quite a challenge.

I take the opportunity to reflect on my own work by teaching composition and improvisation. But ultimately, imparting knowledge and information, trying to be clear and concise, is really at odds with the kind of receptivity and intuition I use in creating my own work.

The financial stability of teaching benefits my practice, and teaching [provides] an ongoing relationship with performers. To be able to plan and create with consistency is the most appealing aspect. This is a relief given the difficulty of securing funding in the sector as an independent practitioner wanting to work with a group, and the additional problem of time lag when you do submit an application.

From an artist WAAPA gains professional experience, knowledge and connection to current practices and industry professionals. For example, I have recently negotiated the acquisition of repertoire for the company from Twyla Tharp—a first in Australia. We will be able to perform 7 of her early choreographic works, which I believe are some of her best, showing the beginning of contemporary dance as we now know it. I have also organised a tour to Europe and Russia for the company with the dancers spending 2 weeks at P.A.R.T.S in Brussels, the dance school associated with Ann Teresa de Keersmaeker’s Rosas Dance Company.

I offer a practical understanding and real sense of the industry which helps students inform their choices when they graduate. I am also providing them with opportunities to connect with the industry. That places them in a much better position once they are out there looking for work.

–

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 12

© Erin Brannigan; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

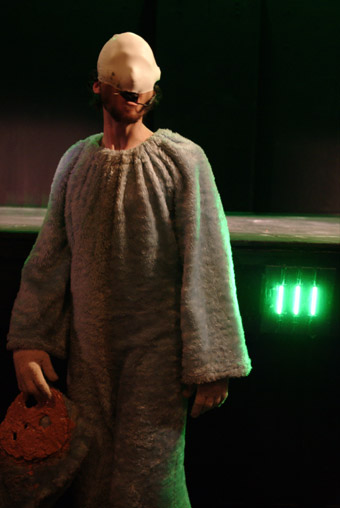

Mark Kimber, Ice

The view from outside might suggest that artists as educators enjoy a somewhat privileged position in that they have steady incomes, access to facilities and networks not readily available to many artists, and perhaps also studio access and professional development opportunities as a part of their employment conditions. They also enjoy the company of peers and connections to professional networks. To cap this off, many receive research funds and professional advancement through exhibiting their work, which they can still sell on an open market in which they might also compete for public and private commissions.

The view from inside is somewhat different. Increasingly these days artist-educators have heavy demands on their time, many of which are not related to their artistic or even directly to their educational practices. Full time tenured positions are the exception, not the norm, and training for most must now continue to PhD level if they are even to be considered for an assistant lecturer’s position. For casuals and many part-timers, pay ceases altogether during non-contact times such as semester breaks and alternative employment must be sought to cover these periods. Against all of these demands the artist-teacher must maintain a viable and respected practice. What for many people might be considered ‘free’ time is more and more absorbed by the competing demands of the studio and the institution.

Five artist-educators practicing within the photomedia field were invited to consider a range of questions about the importance that their teaching practice has for them as artists and the issues, both positive and negative that arise as they maintain a balance between the roles. Central to the discussions was the degree to which their practices as artists and educators were mutually supportive and stimulated each other. The artists responding were: Martin Jolly, Head of Photomedia at the Australian National University School of Art; Kevin Todd, Senior Lecturer, Studies in Art & Design at the University of the Sunshine Coast; Helena Psotova, Lecturer, Photography Studio, Tasmanian School of Art, University of Tasmania; Mark Kimber, Studio Head of Photography and Digital Art Media at the South Australian School of Art; and Matthew Perkins, Studio Coordinator Photomedia, Department of Multimedia and Digital Arts at Monash University.

Helena Psotova, Basel II, 2002, from the series True Fictions

The real thing

Engagement with students seems to be a source of constant stimulation for all respondents. Most cited the continual engagement and debate with students on issues in and surrounding the arts as a source of inspiration, increasing and encouraging a self-critical attitude and maintaining a flexibility in their approach to their own development. No doubt it remains true that students want to engage with a teacher who is aware of issues relating to practice through being engaged with practice. This goes far beyond mere technical issues. Mark Kimber declares that “as an educator and an artist I cannot ask students to take on challenges and risks in their work unless I am constantly doing that myself”, while for Helena Psotova, “the passion for art seems to be validated in [students’] eyes by having a teacher who is active in making art.” Martin Jolly makes the point that the commitment to “the seriousness and importance of art” can only be demonstrated if the teacher is also an artist whose practice remains personally challenging and is more than “just going through the motions of exhibiting.”

Another benefit of engagement with students is the pressure that they exert on a lecturer to maintain contact with technological and cultural changes. Mark Kimber stressed the “sense of energy that invigorates (his) practice that comes from constantly being surrounded by people…discovering the thrill of art for the first time,” something a solo artist can very easily lose sight of.

A model artist?

Some respondents stressed that they did not use their own practice as a base for teaching or as an example for students. This is important because it cuts across the possibility of emulation (always an issue)—students developing an expectation that work like the lecturer’s will be preferred. Issues of maintaining objectivity in relation to the educator’s role are generally foremost in the artists’ minds. Kevin Todd remarks, “I don’t use my own work for teaching as I feel it is important for me to keep that in the studio and to allow for a ‘professional distance’ from students.”

Kevin Todd, (re)creating nature, forms#1 and 2.

Part-time artist

There would seem to be 3 vital requirements for maintaining a healthy visual arts practice—time, resources and energy. Rarely are the 3 available together at appropriate levels. Ironically, the maintenance of one may militate against the other.

The competing pressures for the time of an artist-teacher effect the nature of their studio work in a number of ways. It can mean that the practice is “necessarily sporadic, ‘part-time’, project-driven”, says Martin Jolly. Most only get the opportunity to concentrate fully on their ‘studio’ practice during semester breaks and professional leave which can reinforce the primary identity as artist first and foremost. Some responses suggested that the demands of the institution were too great for the maintenance of practice at the level desired, having become “competitive and time-demanding.” Add personal priorities and this can become a “frustrating and exhausting combination”, says Helena Psotova.

Matthew Perkins says, “The situation where you do not have the time and the energy to dedicate to your practice to the best of your ability can be incredibly depressing.” This is a serious issue for the artist producing work which he or she feels may be below their best, and yet is still under the obligation to exhibit. He goes on to say that at least working within an institution allows him to focus more effectively than a collection of part-time, often non-art jobs had in the past.

The positives

The primary values of working in institutions are tangible and probably quite predictable. They include such things as: a salary; access to equipment and sophisticated technology (vital to the media-based artist); contact with professional networks within and across disciplines; visiting artists and writers; research and curatorial opportunities; travel opportunities and so on. A key but less tangible benefit cited by all was constant contact with peers. Todd said, “I found working full-time as an artist isolating.” The value of an income is obvious but also allows artists the chance to develop independent projects at their own cost, over time and to pursue and develop personal major projects. The institution also allows artists to engage with people in other disciplines on a technical and conceptual level so the resources available often extend beyond the art school.

In some institutions there is a strong recognition of studio-based research. New knowledge and methodologies in practice then ‘trickle down’ into the teaching environment and into the formulation of critical theory. Also educator-artists are constantly involved in self-education; the profession requires this discipline if they are to be relevant and perform at their best. This is inherent in the artist-educator’s situation in the university and may not be so pressing for artists outside of it.

More promotion, less art

On the downside, artist-teachers said that promotion to management level almost always meant that policy planning and administrative duties tended to tip the balance away from maintaining a healthy practice and, in any case, were not part of contact with students, which the artists really enjoyed and found relevant to their practices. Another issue cited was pressure to fit into bureaucratic definitions of research and output in the context of higher degrees and grant funding. Mention was also made of policies that affect the art-training environment, such as a move to more vocationally based training. New priorities for funding universities may not impact well on art schools, so there is some anxiety about what the teaching environment will become. At all levels the increase in administrative work was reported as “steady and constant.” One of the worst aspects of this is that contact time with students is often the first casualty.

The multi-skilled artist

In terms of identity, it is clear that being an artist today is almost never a single activity. Artists tend to be involved in curation, historical, theoretical and critical writing, with artist groups and running spaces, as well as being socially engaged. In this sense the artist-teacher is just another example of the multi-faceted role of the artist.

Balancing act

Some respondents have considered moving from full to part-time to better pursue their practices but, conversely, part-timers stressed the high expectations of the institutions as somewhat unrealistic, including often lower classification and rate of pay for part-time work. Such a shift is only realistic where their practice is generating sufficient income to sustain the balancing of roles, but this point may not arrive until the mid-life of the artist-educator.

Matthew Perkins sums up the artist-educator role thus: “I am equally passionate about teaching as I am about practicing art…It is great to be in a position where I can talk about, in a very passionate way, what I am passionate about. Many professions take this for granted…If I took away teaching and could just practice art then I could achieve so much in my practice just because of time and focus. But teaching is a very satisfying profession. It affects your personal growth in unseen ways—confidence, communication, your ability to critique…It’s a bit of a chicken and egg type equation…To me [the roles] are integral.” This view is doubtless true for all artist-teachers who tolerate the tensions and stresses that accompany teaching for the benefits it continues to bring to their practice and personal growth as artists.

RealTime issue #74 Aug-Sept 2006 pg. 14

© Seán Kelly; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

The Kitchen, director Ben Ferris

Filmmaking, more than most creative pursuits, is not only a collaborative medium; it can also be a very expensive one. Of course, it’s possible to make short films, and these days even features, on the smell of an oily rag, using what Tropfest founder John Polson once described as “a digital camera, some friends and a free weekend.” But those with more vision and ambition need to go through much more preparation, writing scripts, seeking development funding, creating working partnerships and raising the money. And filmmakers, more than most, are used to disappointments and hold-ups: projects are knocked back, people go on to other work, and finances fall apart.

IN FOR THE LONG TERM

Margot Nash, UTS

To get a film into production can take years; take one of our filmmaker teachers as an example. Margot Nash, who teaches at the University of Technology, Sydney, began making films in the early days of the feminist film movement of the 1970s and 80s with We Aim to Please (1977); she was one of the makers of the seminal documentary on women’s work, For Love or Money (1983), with Megan McMurchy and Jeni Thornley; and made her critically acclaimed first feature, Vacant Possession (1995). After a number of years with several projects in development, she was asked to direct Call Me Mum (2006, see review, page 23), which premiered at this year’s Sydney Film Festival. At the first screening, she explained how she had taken a 6-month leave of absence to direct the film, but when the finances fell apart, she went back to teaching half time. Second time lucky, she took 6 months off and made the film, but when she returned to work she still had to finish the sound post-production, so worked three-quarter time while doing that.

Leo Berkeley, RMIT

Film production is a complex, multi-layered activity, and one that some filmmakers are admirably suited to teach, although their reasons for doing so may also be complicated. Leo Berkeley teaches in the School of Applied Communication, RMIT University in Melbourne. His first low budget feature, Holidays on the River Yarra (1991) was critically very well received, but he then spent years working on several follow-up feature projects that never got off the ground. As he explains, he got into teaching as a way of earning a regular income at a stage of his life when he really needed one, and found it occupied most of his time. Recently however, frustrated by the standard processes, he has made Stargate, a 300-minute fully improvised drama with a cast and crew of friends which was screened at last year’s Melbourne Underground Film Festival (MUFF), in the “extreme narrative” strand, while his 12-minute Machinima work screened at the 2005 Machinima Film Festival in New York. (“Machinima, where real time 3D computer gameplay is recorded as video footage and then used to produce more traditional linear videos.” Berkeley, http://conferences.aoir.org/viewabstract.php?id=564&cf=5). “I enjoy teaching film and TV production because students keep you on your toes”, he says. “I like passing on the things I have learnt through experience and my reflection on that experience, and it gives me access to equipment and facilities that are central to my creative practice.” So, is the filmmaker a teacher, or the teacher a filmmaker?

BETWEEN ROLES

Margot Nash tells of “a wise teacher friend of mine (who) once responded to my question, ‘what makes a good teacher’, by saying `I think it helps if you are learning something too.’ Certainly my experience as a screenwriting teacher means I’m constantly learning about film and the craft of screenwriting and this in turn feeds back into my own creative work. I’m a writer-director and I teach screenwriting at UTS which means that I am always on the lookout for interesting films to teach and for new approaches to screenwriting. Reading and analysing scripts and finding constructive ways to respond to student work in order to encourage good work to develop means I am constantly exercising my critical faculties (like exercising the body, one’s critical and creative faculties need to run around the block pretty well all the time to remain sharp). This kind of work can only help me as a practicing filmmaker. I feel very lucky that I am teaching something I am also practicing so I am constantly in a learning situation.”

Trish Fitzsimons, Griffith Film School