Australian

and international

exploratory

performance and

media arts

![Christian Thompson, The Gates of Tambo [Andy Warhol], (2004)](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/7/708_jackson_mfa.jpg)

Christian Thompson, The Gates of Tambo [Andy Warhol], (2004)

From the city’s maelstrom of activity, I ducked down a minor street into a minor laneway, past industrial rubbish bins and hospitality drones sucking back cigarettes and into the eye of the storm: the pure white dungeon that is Spacement. The noises and smells of the city disappeared as I entered Self Made Man. Curator Kerrie-Dee Johns’ motif is the dandy, and with it artifice, subversion and celebration. The dandy has an identity thrust upon him that cannot be refused, only presented back to the world in exaggerated form. Overacting, the dandy demonstrates that identity is always a playing of roles, seducing his audience with suggestive irony and meticulous attention to detail.

In Chris Bond’s The Hitchcock-Feldmar Affair the 8 glass-framed memoranda from Hollywood studio executive Warren Feldmar to Alfred Hitchcock appear aged and worn. Each memo, a day or 2 apart, contributes to a narrative culminating in the death of a woman. The clues are at times hilarious and at others disturbing, sometimes both. Alfred becomes AH and then “that man.” Fingerprint smudges appear–is that blood? Feldmar grows aggressive to the point of paranoia. Is he the killer? Veiled behind this story of rapid psychological disintegration is Bond’s meticulously constructed mockery of the ‘dream factory.’

The modest dimensions of Melanie Katsalidis and Jonathan Podborseck’s 10100 10010 00101 00101 hide its larger significance. The shape, not much more than a foot high, is of a tree, but it’s also an icon, divided into 3 segments which seem to represent the natural world (or rather our response to it), the scientific quest, and cultural endeavours. Approaching this serene work, I felt as I did with Ricky Swallow’s Killing Time–the skill is breathtaking, while the emotional weight of the work is its focus. 10100… is more explicit in its intentions–the self that it expresses is indistinguishable from its political and cultural context. One segment includes a richly ironic quotation, a poetic meditation on trees and their meaning, but also haunting in its broader application: in part, it says, “Civilisation grew from exploiting, destroying, venerating and looking back…”

![Christian Thompson, The Gates of Tambo [Tracey Moffat], (2004)](https://www.realtime.org.au/wp-content/uploads/art/7/709_jackson_tracy2.jpg)

Christian Thompson, The Gates of Tambo [Tracey Moffat], (2004)

I carried this reflection with me to Garrett Hughes’s My Vestige. In the centre of a display of stuffed birds, a framed bird skull and small Victorian side tables is a large photographic print of a man and a woman, behind them a screen like patterned wallpaper or carpet, behind that, an English country estate. The man’s hand is plunged into the woman’s bloody side. She is mostly naked, with the half-drugged look of the archetypal victim. As with Peter Greenaway’s films, the imagery is unnerving, almost overwhelming. Hughes, like Greenaway, insists on closing in on visceral realities, showing our civilised icons up to their wrists in blood. As I inched closer and examined its details–the faces as unaffected as any portrait, the bodies composed of re-collaged parts in a kind of Frankensteinian jigsaw–I grew more and more aware of the constructed nature of the image. Hughes whispers to the viewer that the idea of man as hunter and penetrator is not the only construction of power.

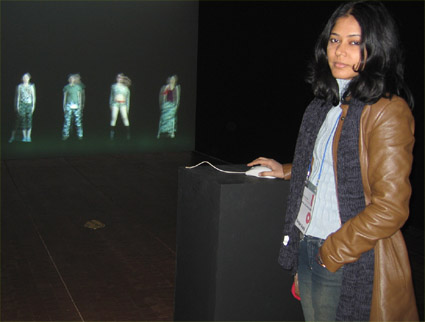

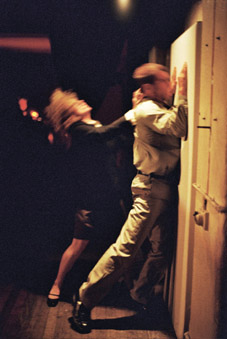

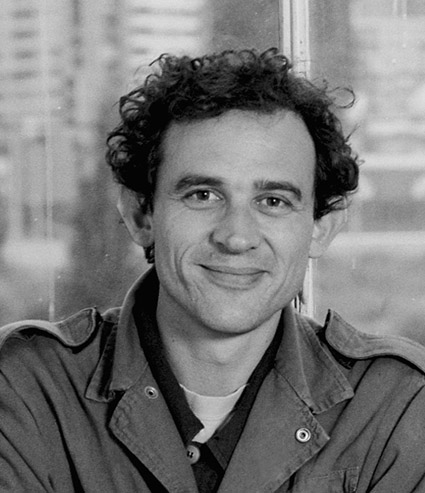

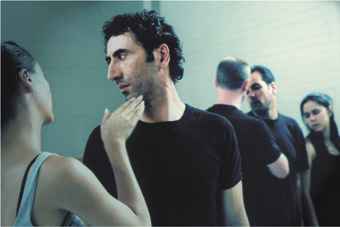

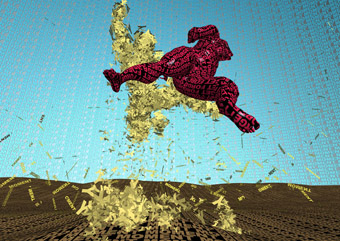

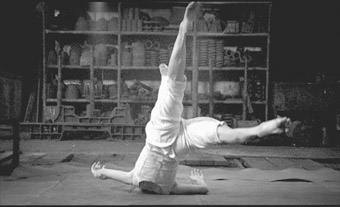

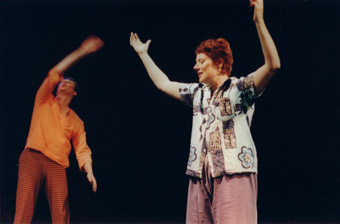

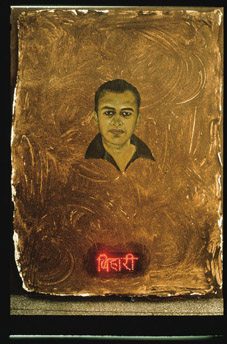

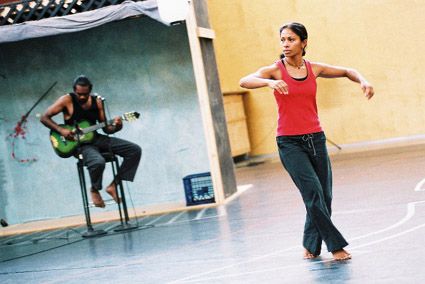

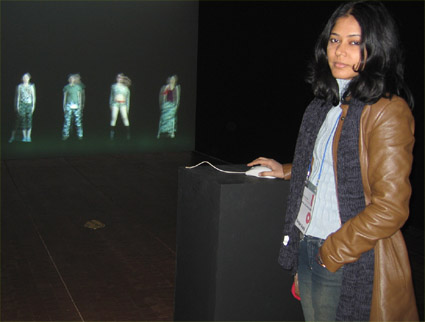

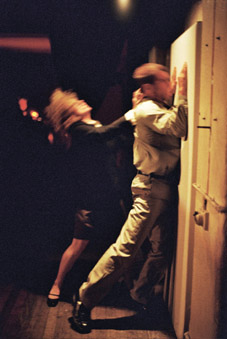

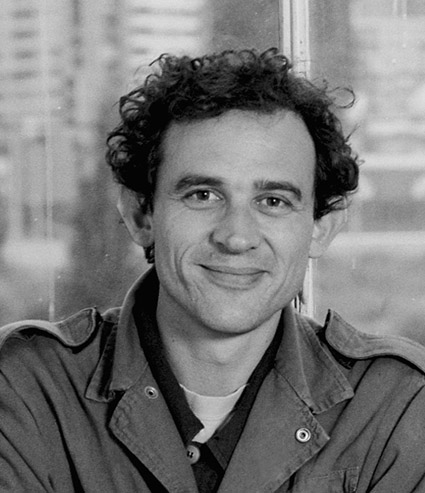

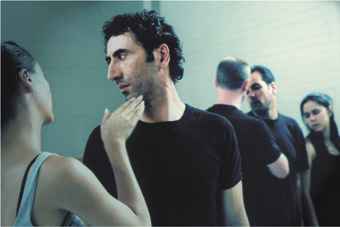

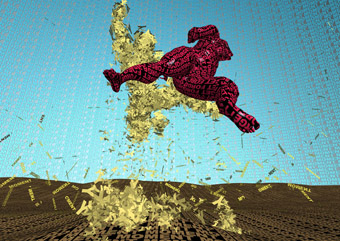

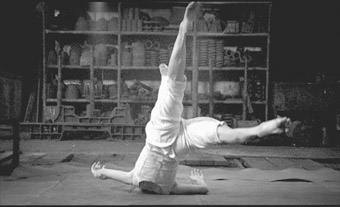

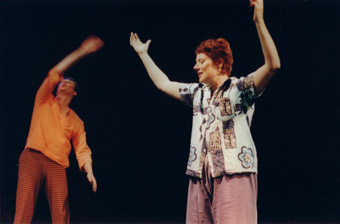

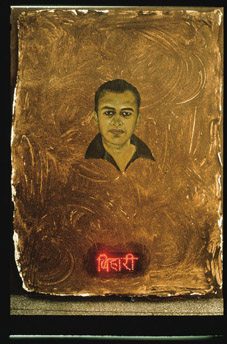

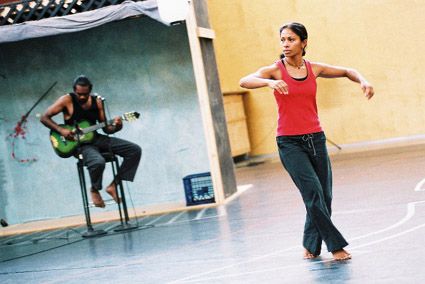

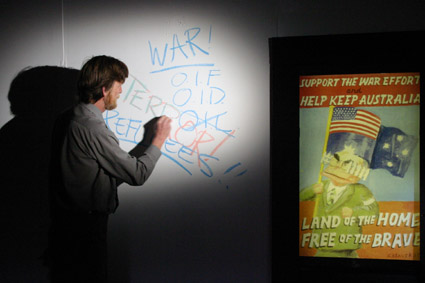

In the 3 four-foot square photographs included here from his Gates of Tambo series, Christian Thompson poses as Andy Warhol, Tracey Moffatt and Rusty Peters (a Gija man from the Kimberleys who took up painting at age 60 after a working life as a stockman). In their embodiment of fame, recognition and cultural heritage, these artists might be Thompson’s natural role-models. He plays them straight, casually, as if expressing an affinity. But, especially as Moffatt, in profile, taking a photograph, wearing lipstick, he simultaneously becomes the focus. As an Indigenous man, Thompson knows that art is never considered merely on its own merits, but also by reference to the artist’s personal history and the way the dominant culture permits and shapes each 15 minutes of fame.

The ‘dandies’ of Self Made Man secure positions from which the foundations of our identities can be glimpsed–the dread of an ever-proximate madness, the flight from nature through its destruction, the compulsory and regulated nature of fame. Leaving this composed but disturbing space, I re-entered the city-storm on the lookout for turbulence.

Self Made Man, curator Kerrie-Dee Jones, Spacement, Melbourne, Feb 1-26

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 13

© Andy Jackson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

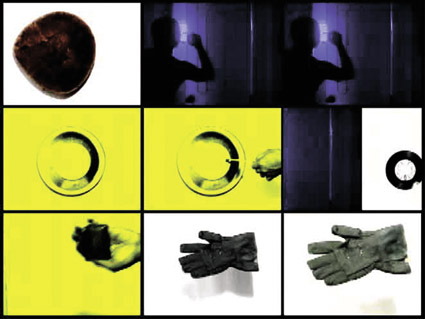

Bianca Barling, Forever, video still

Shimmer’s apt title serves to neatly describe Christian Lock’s holograph and resin wall pieces, Bianca Barling’s richly coloured video and the smooth sleek surfaces of Akira Akira’s sculptures. But the title might also be extended into a more encompassing descriptor, conveying the sense that Shimmer is really about appearances rather than substance.

The works are, for the most part, formally attractive. Christian Lock’s 7 large wall pieces consist of slabs of smooth, richly coloured resin laid over thick swirls of paint smeared on holographic paper. While certainly the most ‘shimmering’ of the works, their interest is more than merely surface, the brush-streaked paintwork providing a 3 dimensional tactility and creating an interior world of infinite detail, despite being impervious inside its resin casing. The works exhibit Lock’s ongoing interest in both the appearance of a material and the material itself, although they replace the previous austerity of colour and frugality of design with gluttonish and lustful over-abundance.

By contrast, the surfaces of Akira Akira’s Snow White I and II are coolly impenetrable. Each curved form lolls on a low plinth like a long white tongue, speaking of the reduction of modernism to a formal template which seems to encompass its aesthetic but not its spirit. Previous work by Akira included subversive touches–objects were shattered and included intriguing details–but these seem docile, blunt, empty, dumb.

In a more literal manner Clint Woodger’s video Sleeper Hold also separates manifestation from its reason for being, combining imagery from the climactic scenes of action films, including explosions, balls of fire, and people leaping, running and being hurled through the air. Deprived of build-up the scenes are also denuded of their power, demonstrating not only Hollywood’s often castigated manipulation of the viewer, but also its reason: without an understanding of the rhythms of time-based work, even ‘inherently’ exciting imagery is dull.

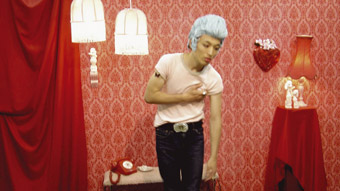

Bianca Barling more successfully builds a completely enclosed world within her film Forever. Visually beautiful and well produced, twin screens are used to depict 2 lovers performing the pain and suffering of love and its end. In their raspberry red rooms, they speak on the phone, look pained and cry, before the girl fires a gun and the boy collapses, clutching his heart. Though its stylised look might be cloying, the romantic watches aghast as the lovers go through their painful motions, heightened by an almost hysterical operatic score in a pantomime both thrilling and heart-breaking.

Sarah CrowEST’s video Globe for Strolling depicts her stumbling about a (soon to be abandoned) local art school campus, sometimes sitting on, sometimes dribbling a large, thigh-high globe, while wearing an identical globe on her head. It’s almost an illustration of the stereotypical indulgences of contemporary art. Rather than being any sort of comment on one’s relationship with self and others, as suggested, its comedy descends into farce as CrowEST struggles to hold her headgear on while blindly staggering along, kicking the globe past a group of students or into a consternated passer-by.

A valiant and powerful essay by Katrina Simmons goes some way towards validation of the works shown. In it, she explains the trials and tribulations of making art and the pitfalls of risk, confusion and failure inherent in the process. Simmons speaks of the artist’s need to discover certain things for themselves, and the inevitability of stumbling a little during the search. Reading it you almost question whether you are wrong for dismissing works as lazy or uninspired. The essay pre-empts other possible criticisms, such as the erosion of a sense of objectivity or meritocracy created by the constant circulation of the same names (CrowEST’s and Barling’s film credits include Akira Akira, while Shimmer’s curator Mimi Kelly also contributed to Barling’s work). Simmons states that Kelly “makes no apologies” for this. A defiant stance? Or a shortcoming celebrated as strategy? Either way, theory doesn’t make up for the oddly self-congratulatory yet dispassionate nature of the works, their reliance on re-visiting old themes and concerns, and the assumption that what is of interest to the artist will necessarily translate into an interesting work of art.

Shimmer, curator Mimi Kelly, Artspace, Adelaide Festival Centre, Jan 14-Feb 27

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 14

© Jena Woodburn; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

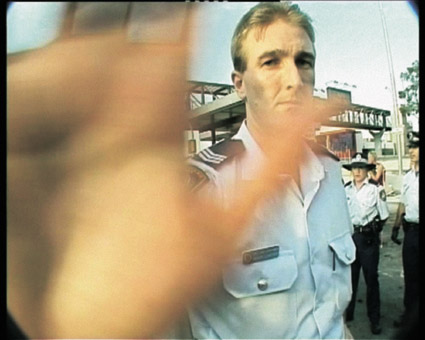

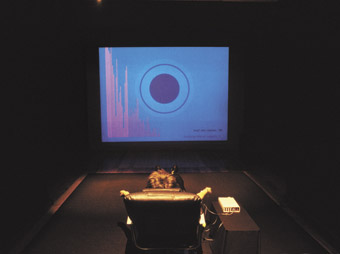

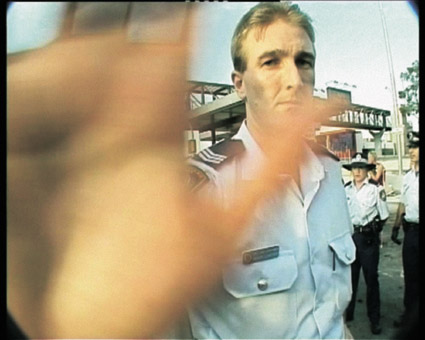

Subclass26A

photo Catherine Acin

Subclass26A

We are deprived of strength when we feel pity. The loss of strength which suffering as such inflicts on life is still further increased and multiplied by pity. Pity makes suffering contagious.

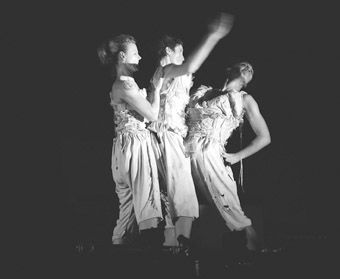

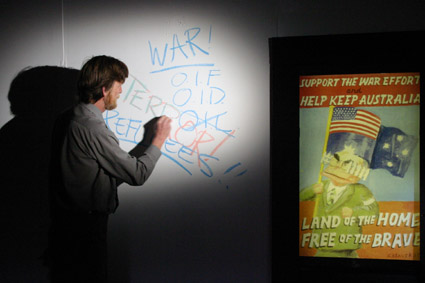

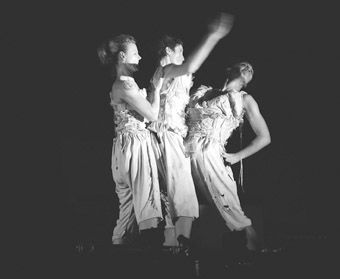

Bagryana Popov’s Subclass26A leaves little doubt about the liberal aspirations of Australian society: when it comes to our refugee policy, don’t bother looking for any. Find instead countless petty cruelties dressed up in diaphanous civility. Subclass26A is a mixture of motion, text, speech and sound. As a work involving dancers and movement, it dramatises human relationships through abstraction. As a textual character piece, it mixes dialogue with naturalism. It also addresses the way in which the nation state imagines and practises its right to exclude.

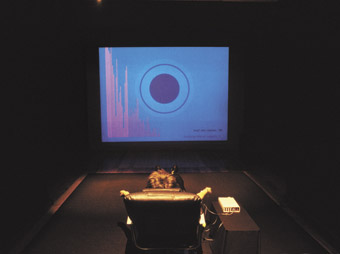

Grey bodies interact in the grey space of detention. Some of them are prisoners, hapless immigrants, others their guards. A few guards are nice, others are less so. Whatever the case, the language is the same. It is designed to destroy people. Bodies jostle over a single musical chair, each sitting and speaking only for a moment. Who are you? Can you tell us in no time at all? Simon Ellis repeats a mesmerising set of gestures. He is at the head of a queue, articulating his self. Inmates wait for their interview, not knowing when it will occur. A man’s face is delicately mauled. One body is able to shirtfront another, to assert an invasion of the other’s personal space. How is it that one person can do these things to another with the sanction of the state?

Is passivity the response? No, there is aggression, frustration, despair, rejection, friendship, withdrawal. Each inmate has an identity. One is from Iraq. He has a story–not that it’s believed. But we believe him. He searches our faces, speaking a language we do not know. His energy pierces the gap between us. Majid Shokor, the man playing an Iraqi is an Iraqi. The real underpins the imaginary. His grace–not dancerly grace, something else–is arresting. In fact, each of the performers is skilled, well chosen.

Despite my sympathies, despite my politics, I find all my perversities come to the surface prior to experiencing Subclass26A. Perhaps I have been reading too much Nietzsche of late. Subclass26A is about our stupid and cruel treatment of refugees, a source of national shame. So why resile from an artwork which addresses such matters? Perhaps it is because I imagine that this work will manipulate its spectator towards some end, that I am to dance when my strings are pulled. However, a work like this operates at many levels. Its differences of style and form are quilted together. The use of percussion throughout the work gives it a Brechtian character in that the drums announce the drama. Yet we identify with the people depicted. Many of the texts used are drawn from Federal Government documents–form 866C, Application for a Protection Visa; a DIMIA draft letter to Iranian detainees; lists of boat arrivals, nationalities–nothing could be more ‘real.’ Yet there are sections which are silent and stylised. Some scenes pin you up against the wall, others let you circle them from afar. The audience strides off knowing that others shuffle towards an unknown destination.

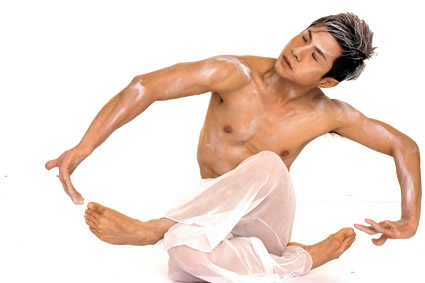

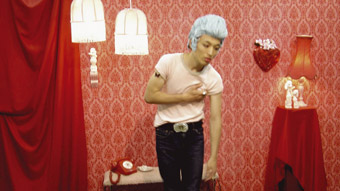

Paul Romano, The Smallest Score and more

photo Heidi Romano

Paul Romano, The Smallest Score and more

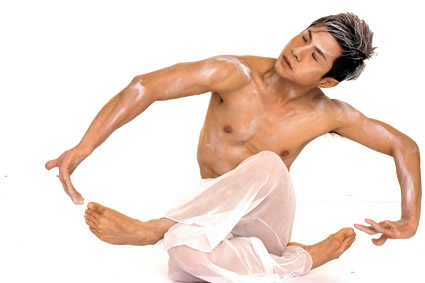

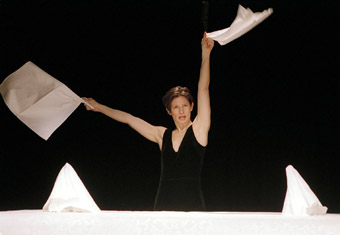

Paul Romano’s The Smallest Score and more consists of 2 pieces: Rapid, performed by Elissa Lee and Paul Romano, and The Smallest Score, a solo work for Romano. Rapid is in sections. The dancers move separately: Lee occupies Dancehouse’s little proscenium stage towards the back, while Romano roams the space of the floor close to the audience. Eggshells crackle as Lee emerges, snaking across the stage: embryonic throbbing. Her looking is phylogenetic, an organism beginning to see the world.

In contrast, Romano simply offers his back to the spectator, crouched low on his haunches: skull-hips-heels. Time passes, he stays. Lee reappears standing, articulating her arms with a percussive, jointed motion, circling her head. She is against the wall, rather than sharing weight with it, beginning to move, arching, turning. She indicates the expanse of her stomach with her hands, a flat square, then twists away, her spine at an occult angle. She is quite beautiful, a see-saw dipping. Light infuses the movement with a quiet quality, sepia-black, contemplative, fluid. Romano performs an incredibly fast series of movements very close to the audience. His limbs, his head, flung in a flurry away from his centre. Repeat, repeat, his speed and proximity a gust of wind that tails off into a chant of panting as he catches his breath. Finally, Elissa Lee is upside down against the wall. We look as if from above, the wall is her floor because, this time, she pours weight into it.

Both Rapid and the ensuing solo proceed as if constructing movement from the limbs, their joints providing the mobility which arises from the gap between bones. The Smallest Score offers Paul as a person, not merely the subject of movement. Here, as before, his sense of flow arises in the joints as he establishes a lexicon of movement possibilities. Although these actions would seem to create machine-like motion, he turns this into fluid movement. Small moments of spinal continuity punctuate an angular succession of gestures. For the spine is intensely mobile, offering a veritable wealth of vertebrae. How is it that the whole of movement is greater than the sum of its parts?

In The Smallest Score Romano reveals his self, allowing us to watch him, engaging us directly with his look. Gobbledygook softens the atmosphere of this serious endeavour, for The Smallest Score and more represents sustained labour on Romano’s part. He asks questions of his work, finding a kinaesthetic through investigation, opening out that process through performance.

Subclass26A, director Bagryana Popov; performers Natalie Cursio, Simon Ellis, Nadja Kostich, Majid Shokor, Rodney Afif, Ru Atma; Fourtyfivedownstairs, Melbourne; Feb 15-25

The Smallest Score and more, choreographer Paul Romano; performers Elissa Lee, Paul Romano; Dancehouse, Melbourne; Feb 23-25

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 16

© Philipa Rothfield; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tim Harvey, Jo Lloyd, Luke George, High Maintenance

photo Shio Otani

Tim Harvey, Jo Lloyd, Luke George, High Maintenance

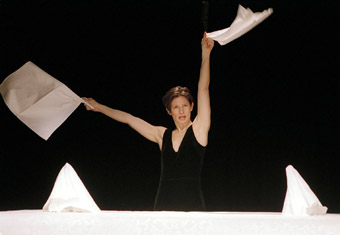

The dance works produced under the amorphous Chunky Move aegis are often characterised by a certain quality, regardless of their subject matter, which can only be described as party. Not celebration, not carnival, but party. From the chaotic, fragmented colour of Arcade to the dark no-tomorrow roar of Tense Dave, there seems to be a regular undercurrent of mad fraternisation which threatens to spill over into uncontrolled mayhem (ironically, last year’s I Want to Dance Better at Parties was their least party-like show). It’s fitting then that Jo Lloyd’s party-themed dance/installation High Maintenance was presented in the Chunky Move studios.

Lloyd graduated from the VCA in 1995 and has been spoken of recently as one of the “most likelies”of the current generation of young choreographers. In the past 7 years she has been developing a distinctive style which takes the nervy freneticism displayed in her work with Chunky Move and Balletlab to a level of more meditative introspection. High Maintenance is billed as a collaboration between Lloyd and fellow dancers Luke George and Tim Harvey, along with designer Shio Otani and composer Duane Morrison.

Audiences are issued with cardboard hats and party whistles as they enter the studio. We are instructed to line the periphery of the space, sitting on mats strewn with streamers, balloons, empty pizza boxes and cartons of beer. Shio Otani’s design appears consciously low key, the festive debris an appropriately haphazard mess. The atmosphere is boisterous and the audience enters into the spirit of things with gusto, filling the studio with chatter and cheer.

When the dancers enter the space we are presented with 3 bodies trying to piece together the events of the preceding night’s party. They shuffle wearily or slip into simple routines. Soon enough they begin to play out echoes of the party’s excesses, reconstructing key moments before returning to their hung-over torpor. Morrison’s dark, beat-heavy soundtrack is densely textured and the performers admirably work with the music without subsuming their movements to its dictates, falling in and out of phrases proposed by the aural soundscape. The lighting design is almost non-existent: house lights remain on for the duration, which detracts considerably from the ambience of the choreography at its most expressive. This is not a work about bodies in pure motion; where it aims to conjure a mood it does so in spite of the dull glare of the studio lights.

There are repeated suggestions of a love triangle, a betrayal, a gunfight, but these are only ever hinted at in stylised form and do not add up to a coherent series of events. The recurrence of certain sequences gestures towards the mutability of memory the morning after. One of the closing images is of Lloyd and George lying half-undressed upon a pile of lurid green streamers, shifting their hips and their centres of gravity to suggest a half-conscious post-coital discomfort without physically touching. Certain images such as this linger after the performance has finished, and though High Maintenance has difficulties adding up to more than the sum of its parts, the striking inventiveness of individual moments is somehow appropriate to its subject matter.

Ultimately, like the characters themselves, we are left doubtful about what really occurred. What is less uncertain is the potential Jo Lloyd and her collaborators display in this original and evocative work.

High Maintenance, concept Jo Lloyd, Shio Otani; choreographers/performers Jo Lloyd, Luke George, Tim Harvey; sound Duane Morrison; design Shio Otani; Chunky Move studios, Melbourne; March 4-5

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 18

© John Bailey; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Selwyn Anderson, Ishmael Palmer, Gibson Turner, UsMob

Perhaps it was the sunny Adelaide weather, the film festival up the road or the post-election sense that serious work is required if the film industry is to survive the Howard era, but in marked contrast to the “air of gloom” reportedly hanging over last year’s Australian International Documentary Conference (RT60, p16), a generally optimistic tone was maintained throughout this year’s event. South Australian Premier Mike Rann kicked off proceedings in an up-beat fashion by announcing an extra $750,000 in state funding for the South Australian Film Corporation (SAFC) and a $600,000 deal between the SAFC and SBSi to fund documentaries with a significant broadband component. The initiative reflects an interest in the multi-platform possibilities of documentaries that dominated AIDC 2005.

Premier Rann’s launch was followed by an identity-affirming keynote address by American writer and academic Richard Florida. His thesis, as detailed in his 2002 best-seller The Rise of the Creative Class, is that the West is currently undergoing a transition to a ‘creative economy’, as significant and far-reaching as the 19th century shift from agrarian to industrial society. Prowling the AIDC stage like a slick self-help guru, complete with head-set microphone and well crafted off-the-cuff comments, Florida argued that the creative class flourished under the Clinton Administration in urban centres such as San Francisco, New York and Washington. In the process, however, blue collar workers in those cities and other parts of the United States felt increasingly threatened by, and alienated from, the new economic order. The Bush Administration is the manifestation of their resentment. Florida argued passionately that the creative class must regain the initiative, but to do so we must work towards a more inclusive creative economy that has a place for everyone.

Not having read Florida’s book, I’m not sure to what extent his speech represented a distillation of ideas more fully developed in print. In broad terms his description of the rise of the creative class and the associated political shifts of the past 15 years contains some truth, but he failed to acknowledge that the concurrent process of economic liberalisation has had as negative an impact on many ‘creatives’ as those in more traditional industries. Many Australian academics, researchers and arts workers of all kinds suffer exactly the same forms of economic disempowerment, instability and exploitation as blue collar workers–as many of those at the AIDC could testify. The so-called creative class is in fact a sector comprising several economic classes, some of whom are a good deal worse off than they were 15 years ago.

Figures cited by the AFC’s Rosemary Curtis later in the conference demonstrated that the kind of creative economy described by Florida is precisely what is missing from Australia’s cultural landscape. Only 36% of Australian documentary directors in the past 13 years have made more than one film. Wages and fees have remained static or declined, and most filmmakers lack stable employment. It wasn’t news to anyone at the AIDC when industry researcher Peter Higgs stated his recent study of the local documentary sector revealed an extremely fragile ecosystem with a tiny capital base rendering it highly susceptible to shocks. But Higgs also reaffirmed a point that recurred throughout the conference, and provided a glimmer of hope for Australia’s struggling sector: online platforms will shortly revolutionise the way we produce, distribute and consume audio-visual material. The Australian media industries need to seize the opportunity to create a sustainable production sector in the new environment or risk being permanently excluded from the 21st century media landscape.

New distribution models

In her AIDC 2004 report for RealTime, Carmela Baranowska identified the off-stage discussions between younger filmmakers about alternative modes of production and distribution as one of the event’s key points of interest. In 2005 some of these filmmakers moved centre stage. The story of how Time to Go John (TTGJ) came about in the lead up to last year’s federal election has already been related in RT65 (p18). The team behind the film conducted an inspiring panel session at the AIDC highlighting how much can be achieved by a motivated group committed to change.

The session was enhanced by the on-screen presence of US filmmaker Robert Greenwald whose internet and DVD-distributed documentaries Outfoxed and Uncovered were key inspirations for the TTGJ project. Greenwald’s real-time image was transmitted from New York via the internet using ultra cheap i-chat technology, allowing him to listen, take questions from the audience and reply with a delay of just seconds. The set up was further evidence of the pan-national lines of communication opened by accessible digital technologies such as those employed by Greenwald and the TTGJ team in making and distributing their films. The session’s encouraging tone was rounded off by Melbourne’s OPENChannel Executive Producer Liz Burke announcing the launch of a Political Film Fund created with the profits from TTGJ. The fund will allocate grants of up to $2,000 towards the completion of political film projects.

Canadian inspiration

In terms of new technologies, the real buzz at the AIDC centred on a series of presentations by representatives of Canadian production companies specialising in interactive content. In marked contrast to Australia, where independent producers lurch from project to project and find it almost impossible to build an ongoing capital base, many Canadian production companies are able to function as viable small businesses with a salaried staff of 2 to 5 people.

This situation has been made possible by regulations introduced a decade ago aimed at creating an economic base for Canada’s creative industries. Whenever a broadcaster changes hands, 10% of the price has to be contributed by the purchaser to the Canadian industry through production funds, investment in training or funding of community-based media. Over 10 years this has created several massive monetary injections. Additionally, all TV channels in Canada must meet quotas of locally produced content and cable channels have to contribute 5% of their gross revenue to the local industry. Generally, 4% goes to the Canadian Television Fund, a private-public initiative with an annual budget of around $237 million (all figures are given in Australian dollars), while the other 1% is usually put into private funds established by the broadcasters themselves. The broadcast company is permitted minority representation on the fund board, but essentially the fund must operate at arm’s length from the parent company.

There are now about 20 private funds which have invested approximately $65 million in the industry. One of the most successful is the Bell Broadcast and New Media Fund, which receives around $5 million annually from the Cable TV company Bell ExpressVu. The fund primarily backs interactive projects associated with a broadcast property (usually a television series) through grants covering up to 75% of production costs. The interactive content generally operates on an online platform. The budget for interactive components of TV series in Canada is typically the equivalent of one broadcast episode.

A range of innovative documentary-related projects underwritten by Bell Fund grants were presented at the AIDC, several of which were aimed at the youth market. Online audiences in this demographic frequently outnumber those tuning into broadcasts. Nathon Gunn of Bitcasters Inc discussed a project in which the website actually generated a broadcast component. Bitcasters were initially commissioned by Canada’s Family Cable Channel to create a site through which children could join a ‘kids’ club.’ Bitcasters created a game-based website that managed to generate a membership of 100,000 with no on-air promotion. Recognising the immense potential of this audience, Bitcasters developed the site with Bell Fund money into an online chat service featuring animated characters who will also feature in a broadcast series.

Patrick Crowe of Xenophile Media discussed 2 projects illustrating the diversity of work backed by the Bell Fund and the flow-on effects created by a funding arrangement that fosters a complementary relationship between television and interactive media production. Toronto’s Rhombus Media, who specialise in music and performance films, required extra funds for a documentary about a lock of Beethoven’s hair. The lock has gone through many hands and had a surprising influence on various people’s lives since it was snipped from the composer’s head on his deathbed. Adding an interactive component allowed Rhombus to apply for Bell Fund money. Xenophile Media were commissioned to create the interactive content and they in turn employed new media artist Alex Mayhew to design an interactive website containing a wealth of material unable to be included in the one hour documentary.

Xenophile Media also received a Bell Fund grant to create an interactive element for the broadcast of the Genie Awards (the Canadian equivalent of the AFI’s). This took the form of a live quiz tied to the content of the broadcast and extra information on award nominees. Interaction took place via the viewer’s television using a window similar to that used in Sky TV satellite services. The interactive component could also be accessed online.

Bell Fund Executive Director Andra Sheffer made the point that projects such as the Genie Awards interactive broadcast attract relatively small audiences and are primarily experiments. The Bell Fund’s mandate is to advance the Canadian broadcasting system, which includes funding untested innovations in interactive media, so that when these experiments evolve into viable revenue streams Canadian practitioners have the expertise, experience and technical infrastructure to become world leaders in providing interactive media content.

Instructive comparisons

The effect of Canada’s funding structures on production activity is starkly revealed by a comparison with Australia, especially on the documentary front. Funding for Australian documentaries represent 3% of the total amount spent locally on audio-visual production; in Canada it’s 12%. Even more telling are the amounts involved: 3% of Australian production spending represents $38 million, while 12% in Canadian represents $416 million. And while domestic box office returns for Canadian feature films in recent years have been even worse than those in Australia, Canada is now the second biggest exporter of television in the world after the United States. They are also positioned to become a world leader in providing interactive content for convergent technology platforms.

UsMob

There was an abundance of Australian talent and innovation on display at the AIDC, and one of the major failings of last year’s conference was remedied with an extensive screening program. Typically, Indigenous filmmaking shone with films like Dhakiyarr vs the King (directors Allan Collins, Tim Murray, RT61, p22) and Rosalie’s Journey (director Warwick Thornton, RT62, p23). Indigenous media was represented by the Warlpiri Media Association and the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association (CAAMA). Veteran filmmaker Bob Connolly was also on hand, reading excepts from his new book about the making of Black Harvest (1991), a fitting tribute to his late partner and fellow filmmaker Robin Anderson. Dennis O’Rourke confirmed his role as everyone’s favourite agent provocateur, appearing on several panels and making fellow speakers nervous with every question. O’Rourke’s Landmines–A Love Story and several other local documentaries premiered at the concurrent Adelaide Film Festival (see p21).

One of the most interesting panels on new Australian content focused on the fruits of the AFC-ABC Broadband Initiative. Several practitioners previewed interactive web-based works which will be rolled out over the next few months, the most outstanding of which was David Vadiveloo’s UsMob (usmob.com.au). This project is based around 7 short films, each with 3 different endings exploring the consequences of particular choices. The films were created and shot by Vadiveloo in collaboration with Indigenous children living in a township on the edge of Alice Springs. Vadiveloo has worked in the area intermittently for a decade, initially as a lawyer on a Native Title claim, then as a filmmaker. His documentary Beyond Sorry (RT63, p17) screened at the Adelaide Film Festival.

UsMob emerged from a request by local Indigenous elders for Vadiveloo to create an online space where Aboriginal kids could see their lives represented. The elders also wanted to encourage engagement with digital technologies, as they fear that the digital revolution will simply represent another barrier for Indigenous kids. The UsMob films were developed from the children’s own stories, with the actual shoots largely improvised on location around pre-planned ideas. The cast comprised the kids and members of their community. Every stage of the project’s development and production was vetted by the community.

The UsMob films are to appear on the web over 7 weeks from late February. The site also contains games, scrap books compiled by the kids during the shoot, and an interactive feedback area where users can respond to the films and upload their own stories and images. The site will not only provide a space for Indigenous kids online, but also link them with children outside their own environment, forging what Vadiveloo calls a virtual “community of consequence.”

The challenge

Unfortunately, the AFC-ABC Broadband Initiative was a one-off round of grants. The projects showcased at the AIDC were as impressive as anything the Canadians had to offer, but it’s difficult to see how the groundbreaking work of our interactive media producers can continue and develop without serious, ongoing investment. This extends into infrastructure: apart from their innovative funding models, Canadians have a major advantage over Australian producers in the area of broadband take-up rates. Nearly 70% of Canadian households have the broadband connections required to carry advanced interactive content; the figure in Australia is around 14%.

There was much talk at the AIDC of campaigning for the establishment of a private fund based on the Canadian model with profits from the Telstra sale. Given the depressing trajectory of the Australian film industry, and the financial strangulation of our traditional funding bodies by the Howard government, structures which provide a degree of long term economic stability for small producers are desperately needed. For all the stimulating talks and great films, for many delegates the AIDC boiled down to one thing–money. I got the distinct impression that the real action was taking place off stage in the lunches and tea breaks, with frenzied card swapping, desperate attempts to solicit broadcaster representatives’ time and nervous corridor pitches to sceptical commissioning editors.

A week after the AIDC, the Canadian delegation appeared at a Sydney forum organised by X|Media|Lab and the Australian Writer’s Guild, focussing on new funding models for Australia’s media industries. Federal Liberal MPs Bruce Baird and Bronwyn Bishop were in attendance, and in his summing up Baird expressed a keen interest in the Canadian models. His positive tone was somewhat undercut by a frank admission that Treasury is determined that all profits from the Telstra sale will go towards servicing debt. Long term investment in creative, informational and educational industries is essential if Australia is to become an exporter of 21st century commodities. The alternative is to become an increasingly irrelevant old economy based on natural resource exports and consumption of overseas goods, generating an ever-growing current account deficit.

The way forward

The insights provided by the Bell Fund delegation provide some working models around which discussion and long-term lobbying of the federal government can coalesce. As Domenic Friguglietti of ABC New Media and Digital Services commented at the AIDC, Australia’s existing funding structures generate tension between an interactive media community and film industry competing for the same scarce resources. The Bell Fund model fosters an artistically and financially complementary relationship between interactive media and traditional film and television production.

The primary message to emerge from the discussions at the AIDC and the Sydney forum was the need for a long term industry strategy and a united voice when lobbying government. The cultural justification for subsidised media production is valid, but holds no sway with those in Canberra. However, the Canadian experience demonstrates that well planned economic structuring by government can create a viable domestic and export media industry not reliant on a constant stream of individual government grants. The Free Trade Agreement with the US is already in effect and there is only a tiny window of opportunity left before the Coalition’s takeover of the Senate and the consequent Telstra sale. It remains to be seen whether Australian documentary makers, and media producers in general, have left it too late to persuade the government to create the necessary economic structures that might allow an Australian creative economy to flourish in the 21st century.

AIDC 2005, Adelaide Hilton, Feb 21-24

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 19-

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Attending the Mobile Journeys forum at Sydney’s Chauvel Cinema in February, it was fascinating to watch the tensions playing out between new media practitioners excited by the aesthetic and financial possibilities of mobile phone art and telco representatives apparently interested solely in company profits. The presentations ran the gamut from market surveys featuring endless figures and pie-charts, to a hyperactive address from Fee Plumley and Ben Jones of the-phone-book Limited (UK) urging us to seize the medium and push aesthetic boundaries: “It’s like the early days of cinema–we’ve got to cross the line to find out when crossing the line isn’t good.”

The forum was part of the FutureScreen Mobile program of masterclasses and forums run by dLux Media Arts between September 2004 and February this year. It’s too early to say what will eventuate in the ground between the commercial and artistic poles represented at Mobile Journeys, but if the ‘MicroMovies’ commissioned for Hutchison’s ‘3’ network shown at the forum are any indication, don’t expect innovative content from our telcos. Short animations like Tightarse Tighthead aren’t exactly exploring a brave new audio-visual frontier.

Mark Pesce of AFTRS’ Digital Media Department argued that telcos will never understand the aesthetic or commercial potential of mobile phones until they start providing content that treats users as social beings first, and consumers second. Pesce’s claim is supported by Anna Davis’ feature report examining global developments in phone art. Installations such as Blinkenlights (Chaos Computer Club, Germany) employ phones as points of interaction in works that directly address a wider community. In other words, they treat phones as network devices rather than delivery points for pre-made content.

Having said that, at least some of the local interest in mobile phones has come from filmmakers desperate for any outlet in a media landscape increasingly bereft of Australian content. My AIDC report details some of the alternative funding models presently being discussed to address the general downward slide in Australian documentary and drama production. But even the mixed public-private structures outlined by the Canadian delegation at AIDC require a governmental commitment to the industry. An essential part of this is content regulation: in another short-sighted move at the end of March the federal government rejected the Australian Broadcasting Authority’s recommendation to introduce local content rules for the 10 documentary channels on Australian pay TV. Locally made documentaries comprise just 4.9% of the content on these channels, with the vast majority of programs repeated from free-to-air. Without regulation, this figure is expected to decline; a familiar story of Australian talent being stymied by the limited vision of our political and corporate leaders.DE

–

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 20

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Justine Clarke, Look Both Ways

As I spent a week moving between the Australian International Documentary Conference (AIDC) and the Adelaide Film Festival, the contrast between the 2 events became stark. While AIDC was all money, funding structures, frenzied networking and industry talk, the AFF was unabashedly a cultural event, complete with gala opening, premieres and international guests. In initiating the festival in 2003, SA Premier Mike Rann set out to differentiate the event from others here and overseas with a film investment fund, allowing the AFF to help produce as well as screen new works. This lent an extra charge to opening night, as the festival unveiled the first feature film made partly with AFF money.

Look Both Ways

Look Both Ways is the debut feature from Sarah Watt, previously known for her darkly original animated shorts. Set in Port Adelaide, the film revolves around the mysterious death of a young man under a train. Rather than constructing a tight linear narrative, Watt’s story follows various characters as they orbit around the man’s death, creating a snapshot of life in an Australian suburban milieu. The camera lingers on the streets, parks and wastelands that characterise the edge of all Australian cities, capturing the sense of Port Adelaide as an in-between zone that’s neither white picket fence suburbia nor dense urban space. The characters also convey a sense of being caught ‘in-between’, trapped in a position of stasis in their private lives and careers.

Look Both Ways is also notable for a degree of formal innovation, with Watt’s background evident in brief passages of animated watercolour fantasies bursting forth from the mind of one of the protagonists. The meditative pace is further punctuated by sequences of rapid fire editing unleashing impressionistic flashbacks. Watt’s mixed approach to film form, the nuanced performances and wholly convincing dialogue make for a quietly evocative film that manages to depict contemporary Australians without ever lapsing into crudely drawn stereotypes.

Documentary

The opening night of the AFF also saw Australian documentary auteur Dennis O’Rourke presented with the Don Dunstan Award for his outstanding contribution to the Australian film industry. Landmines–A Love Story, his latest account of a personal encounter with the world’s dispossessed, premiered at the festival (see p25). The AFF’s other key documentary debut was Cathy Henkel’s I Told You I was Ill: Spike Milligan. As one of the AFF Investment Fund recipients, Henkel’s film received considerable hype and the premiere was a festive affair, with Mike Rann and members of Milligan’s family on hand to introduce the film before a capacity crowd.

I Told You I was Ill was an enjoyable and intimate portrait of the Milligan clan, but I was less convinced it fulfilled Henkel’s promise to “show us a side of Milligan we have never seen before.” The extensive home movie footage was fascinating, but the film as a whole revealed little about the comic that hasn’t been said elsewhere, and the use of animated characters drifting across screen during interviews came over as twee rather than Milliganesque. In the midst of festival fever it was hard to judge the extent to which the film suffered from over-promotion; one of the dangers of an investment fund is the enormous weight of expectation placed on the festival products. In fairness to Henkel, it must also be said that an unfortunate technical problem meant only part of the soundtrack was audible at the debut.

On the international documentary front, one of the most remarkable films was Kim Dong-won’s 3 hour epic Repatriation, detailing the fate of “unconverted” North Korean spies living in South Korea. The film’s subjects were imprisoned in the early 1960s and endured harsh conditions until released in the early 1990s during South Korea’s transition to a civilian government. With no access to support or medical services, and cut off from their homeland, the North Koreans eked out an existence performing menial jobs. When one of them moved into Kim Dong-won’s neighbourhood, the filmmaker began recording their interactions, and the ex-spy introduced him to a wide network of comrades trapped south of the border.

Repatriation is part verité study of individuals caught in the currents of history and part cinematic essay on the tragic history of modern Korea. Having been raised on a diet of rabid anti-communism, Kim initially finds the ex-spies’ devotion to North Korea simultaneously puzzling, endearing and disturbing. Their refusal to countenance talk of North Korean atrocities is troubling, but their treatment by South Korea is hardly an advertisement for capitalist ‘freedom.’ In extended interviews they detail the brutal torture they endured in prison as authorities tried to forcibly convert them. Kim tracks down ex-prisoners who did renounce communism, and in contrast to the proud “yet-to-be-converted” (South Korea’s term for recalcitrant prisoners), finds them deeply traumatised by their betrayal of the socialist cause. Ironically, Kim also finds himself persecuted by South Korean police for talking to the former spies; at one point his office is raided and all footage is confiscated.

Far from being brainwashed ideologues, the ex-spies come across as men of principle, deeply committed to socialist ideals and genuinely distressed by the selfish competitiveness of South Korean society. Their desire to return home was so strong that I found myself dreading the deep disappointment, disillusionment and possible persecution that they would surely endure if repatriated. Eventually they are allowed to return home during a brief period of détente at the turn of the decade, and Kim attempts to visit North Korea to report on their fate. An opportunity to visit Pyongyang as part of a delegation covering official celebrations does arise, but he is prevented from leaving Seoul by South Korean authorities–he is still under investigation for his contact with the North Koreans. A friend is able to make the journey and bumps into the ex-spies as they are being transported to partake in the celebrations. They appear radiantly happy and in markedly better health than the aged, harassed figures we see earlier in the film. The work’s most poignant moment sees one of the men speaking directly to camera, declaring Kim Dong-won to be like a son. “I miss you” he says. In this one scene the entire tragedy of the Korean peninsular falls into focus; like Kim, we feel the yawning chasm of political, cultural, and military barriers separating us from men we have come to know. Repatriation achieves a compassionate humanism without ever sidestepping the complex cultural and ideological divisions that plague post-war Korea.

Machuca

An historical theme was also evident in one of the festival’s feature film highlights: Andres Wood’s Machuca. Dramatising life in Chile’s capital in the months leading up to, and immediately following, the bloody coup of September 11 1973 that deposed Salvador Allende’s elected government, Machuca captured the sense of unrest that characterised the period, and the disquiet Allende’s empowerment of the poor caused Chile’s middle-class. It also doesn’t shy away from portraying the middle class’ complicity in fostering the air of reaction that led to the coup.

Machuca does not, however, demonise the wealthy, nor canonise the poor. One of the film’s most revealing aspects is the middle-class horror at the brutality of the military crackdown when it finally happens, and the extent to which all Chileans suffered under the repression. The film’s portrayal of military violence was a surprise given the still-contested nature of the period in Chile itself. Machuca was Chile’s biggest ever domestic box office hit, perhaps signifying the country is ready to begin exorcising the lingering trauma of the Pinochet years.

Café Lumiere

Finally, on a more peaceful note, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumiere provided a centre of calm in the festival. A young woman attempts to locate the spaces inhabited by a Tokyo jazz musician of the 1920s which have long since been erased by bombs and redevelopment. Her friend obsessively travels the Tokyo subway, recording its sounds in order to find the system’s ‘essence.’ Hou constructs a beautiful film about space with minimal dialogue and narrative development, and obsessive framing of the highly urbanised environment through which the characters move. Tokyo becomes a network without beginning or end, in which people’s lives casually intersect and move apart in an endless, seemingly random pattern. An intertitle dedicates the work to Japan’s master of on-screen spatial relations, Yasujiro Ozu.

Festival identity

There were many other gems among the sample of films I caught at the AFF; space precludes mentioning all of them. Director Katrina Sedgwick created an innovative program and has worked hard to give the AFF all the trappings of an international festival. It was deeply refreshing to see Premier Rann not only providing financial backing for an Australian cultural event and the making of films under the festival’s aegis, but also lending support through his enthusiastic presence. However, the fact the festival is so closely identified with Rann raises the question of its fate when the Premier eventually leaves office. If the AFF is to succeed in becoming an important date on the international film calendar it needs the kind of sustained support and investment that has seen Pusan become Asia’s key film festival.

Adelaide Film Festival 2005, Feb 18-March 3

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 21

© Dan Edwards; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Mon Tresor

How does anyone learn to be a visionary? It’s one thing to make the notion of “visionary filmmaking” a rallying cry, as Peter Sainsbury did in his wonderful 2002 speech (RT53 & 54) urging filmmakers and members of funding bodies alike to take more risks and trust their individual judgement. But it’s quite another for a government organisation to put this philosophy into practice in a systematic way. If you believe the publicity, this is the Australian Film Commission’s aim with their new IndiVision initiative, which draws on the $15 million promised last year by the federal government to fund low budget features.

Besides funds for script development and production, the program incorporates an annual Project Lab (held for the first time in February) where 8 filmmaking teams get to discuss their projects with local and international advisors. According to the AFC’s Director of Film Development, Carole Sklan, one aim of the Lab was to encourage participants to try new approaches, in an exploratory rather than prescriptive fashion. Thus the workshops were accompanied by a touring program of recent international low budget features (most from first time directors) meant to illustrate the range of stylistic and dramatic options possible on a low budget. The blurbs for the screenings even hint that lack of resources can benefit a film by stripping it down to essentials like script, performances and a strong basic concept–though Sklan stresses that it’s films, not just scripts, which are being developed.

Some cracks in the IndiVision approach start to become visible here, and while the screening program was a worthwhile experiment, the actual films shown proved less than inspiring for this viewer. It’s easy to imagine Australian equivalents to Tully (Hilary Birmingham, USA, 2000), or The Station Agent (Tom McCarthy, USA, 2003) but by the same token they don’t add much to the local tradition of understated naturalism. A tasteful heart-warmer about misfits bonding, The Station Agent is the kind of movie where a set piece consists of the main characters taking a stroll along a railway track, eating some beef jerky and coming home (“That was a good walk!”).

Other selections register as more hip but not necessarily more substantial. Heavily reliant on post-production effects and attractive young faces in close-up, Reconstruction (Christoffer Boe, Denmark, 2003) is a lightweight metaphysical enigma, typical of one brand of current European art cinema in its reality shifts and musings on the contingency of love. Stylistically the most thoughtful of the bunch, Mon Tresor (Keren Yedaya, Israel/France, 2004) shows a teenager’s descent into prostitution in long takes that lend a classy austerity to the sordid subject matter. But by the end it’s hard to see what purpose was intended, unless the spectacle of misery is taken to be fascinating in itself.

Asked about the weaknesses of current Australian cinema, Sklan cites “a certain emotional timidity” as a problem to be addressed. “Audiences want to laugh and cry…they want a special, unique, transporting experience.” Though I wholeheartedly agree, her words suggest a potential difficulty with the entire initiative: the ‘visionary’ aesthetic outlined in Sainsbury’s address is basically a refurbishment of modernism, hence reliant on ambiguities that often block easy emotional response. Yet the evasion of direct feeling tends to be experienced by at least some viewers as a betrayal. This may explain why the screening program steers away from the zanier and more wilfully baffling trends in modern film narrative, from Gerry (Gus Van Sant, USA, 2002) to Tropical Malady (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Thailand, 2004). As professional performances and well written scripts aren’t priorities in films like these, it’s unclear how far they’d be aided by a craft-based development process, while the maximalism of a film like I Heart Huckabees (David O. Russell, 2004) might be problematic in a different way.

Of course there are approaches allowing filmmakers to combine emotional directness with unobtrusive formal experiment–some of Mike Leigh’s recent films are exemplary here. It’s easy to see why the program flashes back a few years to include Thomas Vinterberg’s Festen (Denmark, 1998), the best-known example of the supposedly gritty, truth-telling Dogma style. But as Lars von Trier’s antics made clear at the time, there was always a satanic side to the Dogma pact. Paradoxically flaunting its lack of artifice, Festen’s camera work mocks the ‘transparent’ innocence of home movies, while its shock-horror revelations remain close to the conventions of the well made play [the post-film stage version of Festen is playing internationally, including Australia in 2005. Eds].

Though this gloating duplicity is undeniably ‘modern’, later works that draw on the Dogma idiom tend to indulge the craving for raw emotion without irony–as in the mawkish if sometimes affecting 16 Years of Alcohol (Richard Jobson, Scotland, 2003), also included in the screening program. Again, it’s hard to see what purpose is served by this emotional button-pushing, apart from “working through” personal trauma which here as elsewhere arises from the family, with broader significance implicit at best. But in a postmodern, anything-goes context, it’s hard to find the shared vocabulary which would even allow such issues to be debated.

More easily discussed are the challenges of economics. It’s little wonder that local filmmakers are reluctant to take risks given the restrictions imposed by low budgets, the difficulty of attracting audiences to any kind of Australian cinema and the ongoing need to locate additional funding sources to stay in the game. Yet in the ever expanding international marketplace there’s no way anyone can sustain an art film career by playing it safe. In Australia today, it takes all the ingenuity of a Rolf de Heer to walk this tightrope, and while his shifts and dodges command admiration it’s questionable whether his movies have gained as a result.

Still, one can hope that the would-be filmmakers who consulted with him at this year’s Project Lab picked up a few tips. As Sklan ruefully admits, whatever can be done to facilitate ‘vision’, everything ultimately comes back to the resources of the individual. “We set up a low-budget initiative but it came from us, the AFC. It should have come from the filmmakers themselves. All we can do is set up the possibilities and say, ‘What do you want to do with them?’”

The next deadline for AFC low budget feature production grants is July 15. Applicants can apply for up to $1 million. The next deadline for the IndiVision workshop and development funding is September 2. The workshop is open to filmmakers of all levels. See www.afc.gov.au for details.

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 22

© Jake Wilson; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Tenho Saudades

I torture the film in any way I can think of.

Louise Curham, RT58

Louise Curham is at the forefront of Australian moving image art. As well known for curating innovative expanded cinema events in non-traditional exhibition spaces as for provocative Actionist performances, Curham is highly regarded in the experimental film world for her work using “obsolete media.” Her hand-worked Super 8 films reinvent the home movie medium of years gone by.

Her new film, Tenho Saudades, showcases Curham’s continuing (some would say consuming) obsession with physical mark-making and intervention in the filmmaking process. The work consists of Super 8 footage which has been subjected to a range of interventions (hand painting and other ‘direct animation’ techniques including scratching, bleaching, and collaging) along with a male voiceover. Some found footage (including a millisecond of a bemused looking Bert and Ernie!) and pieces of optically printed and re-shot film strips are interpolated with treated footage shot in Brazil by collaborator Peter Humble. The layered soundscape carefully juxtaposes various pieces of music–a Bach fugue, Brazilian drumming, club techno–with traffic and street noises. For most of its 18 minutes, the male voice narrates, unusually in the second person, a visiting male performer’s encounter with the gay underbelly of Brazil: “You have a map. In red pen you mark the location of gay clubs. The first one you can’t find. The second one, it’s packed. Groups of guys, drinking, laughing, dancing. Are gay clubs the same all over the world?”

This voice-over may not be to the taste of all avant-garde film lovers. Viewed without the sound, it is certainly pointless to construct much of a narrative from seemingly random images of a South American city collaged with hand-processed film. Screened silent (as many avant-garde films are, to avoid the melodrama inherent in what Stan Brakhage famously termed the ‘grand opera’ of narrativity), the film is–typically of Curham’s work–nothing short of a visual orgasm of sublime colours, textures and forms. The intense sensuality of the bands and strips of film bleeding, weaving and colliding with each other is exquisite, as are Curham’s signature jewel colours–explosions of amethyst, emerald, amber and sapphire, the result of her alchemical explorations in hand-processing.

With the sound added Tenho Saudades joins an international conversation with other experimental films that explore themes of gay identity and interracial romance. It invites comparisons with Karim Ainouz’s Paixo Nacional (1994), a beautiful 16mm film about a young Brazilian man fleeing homophobic persecution in his homeland, intercut with touristic images of Brazil as a land of sexual license. It also brings to mind films by the highly acclaimed German queer artist Matthias Muller, whose works such as The Memo Book (1989) also evoke emotions through complex manipulations of film material and lyrical abstraction.

Contextualising Tenho Saudades in the field of gay experimental film/video, which emphasises masculine subjectivity and formal manipulation, perhaps ameliorates some of the ‘pure film’ concerns about the voice-over, since it functions as an aesthetic genre marker.

Curham famously ‘performs’ her film works with noise orchestras and other musicians, darting between multiple projectors, adjusting them, turning them on and off. This suggests that there may be multiple ways of seeing Tenho Saudades: as a gay experimental film, as an aesthetic object evidencing its maker’s fine art training, and, given its poignant title (which means ‘I miss you’), as a hymn to a dying medium. Whichever way you see it, Tenho Saudades is an extraordinary film.

Tenho Saudades, images by Louise Curham, voiceover written and performed by Peter Humble, 2005

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 22-

© Danni Zuvela; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Heimat 3

This year’s Festival of German Films presents a culture increasingly engaged with the political, economic, social and personal problems that have emerged in a reunified Germany at the epicentre of the trans-national experiment that is the European Union. The reunification theme is most extensively addressed in Heimat 3, one of this year’s highlights. There are also the latest insider reflections on the Nazi period, controversially addressed in the festival’s other key film, Downfall.

Hitler the human

Directed by festival guest Oliver Hirschbiegel, Downfall (Der Untergang) has been a commercial, if controversial, hit in Germany. This first German account of the last days of the Nazi regime inside the Chancellory bunker has attracted criticism for treating Hitler’s inner circle as ‘human.’ Besides Goebbels (who appears pathological), the military and political leaders surrounding Hitler are recognisably ordinary; they could be the servile, if tense, senior advisors surrounding any multinational’s CEO. Downfall refuses to metaphysically ascribe evil to the Nazi regime. The benefit of such a prosaic portrayal is that Nazism can be seen as an exaggerated playing out of radically regressive elements within other historical and political moments in Western culture, including our own.

Although in theory an important advance, the film tends to overplay its demythologising strategy. While it is valid to undermine a view of the Nazi period which pretends that present-day politicians, business leaders and ordinary people wouldn’t or don’t collaborate with the power elite of the day (no matter how appalling its ideology or actions), the film seems to assume that the only recognisable humanity is a redemptive, ‘positive’ one. Hence there are often overly sympathetic portrayals of Nazi figures, belying their complicity in the horror of Nazism, the war and the Holocaust. Professor Schenk, for example, is portrayed as a selfless medical doctor tending the wounded, even though in reality he was a senior SS and Wehrmacht officer implicated in experiments using Dachau concentration camp prisoners.

The most controversial figure is the seemingly ‘passive’ or even sympathetic witness through whose eyes the film unfolds, Hitler’s 25 year old secretary Traudl Junge. She looks on with blank bewilderment and apparent compassion for her boss as the Nazi facade implodes. The film ends with the real-life aged Junge describing her realisation that ignorance and naivety are no excuse. Meanwhile the presentation of Hitler himself is far more complex, and truly disturbing. As played by master Swiss actor Bruno Ganz, the Fuhrer looks like a fallen hero shaking with Parkinson’s disease and a mercurial temper wrought from the failure of his warped dreams–”a would-be Siegfried who has collapsed into Alberich”, as David Denby puts it, invoking the Wagnerian mythology of power-deformation (The New Yorker, Feb 7, 2005). In a horrible and darkly moving performance this Hitler is both atrocious and almost humorously pathetic.

In the film’s determination to bring Hitler’s regime down to earth, Nazism has never seemed so banal. But while this may resonate with Hannah Arendt’s seminal analysis of evil in Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), in Downfall it often seems to result in a kind of subdued reassurance, as yet again we see the 20th century’s central monster resuscitated and satisfyingly killed off. This is emotionally understandable, but seems more the product of fear and ritual catharsis than analytical insight. Downfall is definitely worth seeing and arguing about–it is far preferable for a nation to over normalise or de-mythologise the darkest moment of its history than to re-write or avoid it entirely.

Heimat: intimate epic

Weighty themes are played out on a much larger canvas with the latest instalment of the Heimat series, written and directed by Edgar Reitz. This is the third cycle of Reitz’s films around the theme of 20th Century German cultural identity and ‘heimat’ (the closest English translation is ‘homeland’). The first 2 were released in the 1980s and 90s respectively. Heimat 3–A Chronicle of Endings and Beginnings (Heimat 3–Chronik einer Zeitenwende) comprises 6 films covering the period from 1989 to 2000.

The emphasis is on personal and small-scale layers of social history as the films follow the fortunes of famous conductor Hermann (played by festival guest Henry Arnold) and singer Clarissa, who meet on the night of November 9, 1989–the evening the Berlin Wall came down. They impulsively rekindle an ancient affair and buy an old cottage outside Schabbachm overlooking the Rhine River near the Luxembourg border (Hermann’s fictionalised rural hometown from the first Heimat series). They then set about rebuilding their blatantly symbolic house once occupied by a German Romantic poet. The first film in the series proceeds to set up both the hopefulness and one-sided economic and political reality of a reunified Germany, with East German builders and engineers coming to the West to rebuild the house.

Like its predecessors, Heimat 3’s intimate approach to epic themes is both a central strength and weakness. Sometimes I was yearning for a more ‘big-picture’ context to glean a deeper, more politically engaged historical analysis of post-reunification Germany, but also to nullify criticisms that Reitz soft-pedals the more politically problematic aspects of the notion of ‘heimat.’ Although representing ultra urbane values, Hermann is very tolerant of his family and the village from which he once fled, and his character is rather bland, too perfect. One angst-ridden visit to a brothel accounts for the only time in which he appears anything but a successful yet sensitive, attractive and highly cultured German man who wants to enjoy the bucolic charms of the Rhine Valley when not conducting in the concert halls of Europe. His profession could have been more thoroughly utilised to comment upon Germany’s cultural heritage and the role of art in social, cultural and political change. Then again this may have detracted from Reitz’s rural vision of reconciliatory ‘heimat.’

As it develops, Heimat 3 becomes more adventurous, dark and complex in its intimate yet epic portrayal of post-reunification Germany. While the whole enterprise at times plays out as high-class soap opera, it is definitely worth devoting a day to see these films. The sheer ambition and scope of the entire Heimat series makes for a substantial dramatic engagement with contemporary European history and culture. That such an engagement comes from a filmmaker working in Germany, a modern yet tradition-obsessed country that has been home to the very best and very worst of Western culture, makes for compelling viewing.

Reconciliations

While it is not as immediately concerned with reunification as Heimat 3, the union of East and West is also a theme in last year’s most commercially successful German film, Go for Zucker. Directed by Dani Levy, it tells the amusing story of a pious rabbi from the former West Germany who meets his much poorer, ‘Godless Communist’ brother from East Berlin when their mother dies and they have to resolve their differences before her will can be read. Described by the festival as “the first post-1945 German-Jewish comedy made in Germany”, the film offers a humanist, reconciliatory message while making some telling social points about a self-described “loser of reunification.”

Other films to screen at the festival this year include: Agnes and His Brothers, another humanist comedy about siblings (centred this time around sex and politics); Kebab Connection, in which a young Turkish hip-hopper aspires to make the first German kung-fu film; Napola (directed by festival guest Dennis Gansel), the story of 2 boys in 1942 who attend a training school to become elite Nazi soldiers; And I Love You All, a documentary about a Major who worked for the GDR’s Stasi secret police for 20 years; and Música Cubana (produced by Wim Wenders), the semi-fictional tale of the formation of a band made up of younger generation Cuban musicians.

Festival of German Films 05, Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra; April 14-May 1

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 24

© Hamish Ford; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Landmines—A Love Story

It has become a cliché to describe veteran documentary maker Dennis O’Rourke as a “controversial” filmmaker. He welcomes the tag, but not its negative implication: “In this frightened country of ours, some people use the word controversy as a pejorative term; to me it’s not a pejorative term, it’s the most apt adjective to apply to an artist.” O’Rourke’s record of commercial and artistic success, passion for the art of documentary and ability to speak frankly qualifies him to provide a unique anatomy of contemporary documentary practice.

O’Rourke believes that an aversion to revealing uncomfortable truths lies at the heart of a particular malaise: “Sad to say, most documentary films are bogus. The documentary does attract a certain kind of earnest artist manqué. They’re less concerned about the art, which is where the true revelation can occur, than in being on the right side of things, and making statements to the converted. But what they never allude to and inscribe in their work is the fact that there’s always a contradiction, another side to the story. It’s almost like you’re supposed to be a social worker with a camera.”

After the altercations surrounding The Good Woman of Bangkok (1991) and Cunnamulla (1999), nobody will mistake O’Rourke for a social worker. While his latest work, Landmines–A Love Story, is destined to be less of a hot button film, it remains topical and urgent. It is one of a spate of recent Australian documentaries connected to Afghanistan. Others have including The President versus David Hicks (directors Curtis Levy, Bentley Dean, 2003, RT63, p23), Molly and Mobarak (director Tom Zubrycki, 2003, RT60, p15), Letters to Ali (director Clara Law, 2004, RT64, p20) and Anthem (directors Tahir Cambis, Helen Newman, 2004, RT62, p18). Each of these films tangentially links Australia with the Afghan war or the oppression of the Taliban regime and the consequent refugee crisis.

While O’Rourke likes some of these works, he says they’re different from his because the subjects are “already media types in an external situation”, allowing viewers to still think of Afghanistan “as a place where life is so repressed, and not quite as human as we know it.” In contrast, in Landmines O’Rourke was “able to destroy that whole stereotype of what it means to be an Afghan man and an Afghan woman.” Adhering to a template he has developed over the past 2 decades, mixing intimate portraiture reliant on interviews with observational footage, Landmines evokes a strong sense of personality and place. The film was shot in Kabul immediately after the American invasion of Afghanistan.

On his first day, O’Rourke came across Habiba, a burka clad woman with a prosthetic leg, begging in the streets. Shrugging off his translator’s attempts to divert him, O’Rourke made contact with her. Thus began a collaboration which led into Habiba’s home where she could remove the burka and talk intimately about love, men, family, politics and the day her leg was blown off by a Russian landmine.

According to O’Rourke, he didn’t begin with the intention of having a female protagonist. “I didn’t know what sort of a love story it would be. All I had was the title. I thought that with such an amorphous title it could end up being a triptych, because there’s love of different kinds. The Russian and American military love their landmines, then there’s all the love in ordinary people like the teachers in the de-mining classes.”

Ultimately though, it became Habiba’s film. O’Rourke’s depiction of her is loving, but in no way anodyne. He reveals a feisty, flesh and blood woman who occasionally goes crazy when stuck at home with the kids, gets lippy with a policeman trying to move her on while she begs, and glumly suffers a lecture from a health professional about the need to re-train or find a job. The image presented as the camera pulls back from this final encounter achieves a special resonance-–Habiba’s interrogator and her colleagues are all amputees. It’s a moment that recalls the level of surreal pathos in Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Kandahar (Iran, 2001) when landmine victims rush across the desert to collect limbs parachuting from the sky.

Of all O’Rourke’s work, Landmines… most resembles Half Life, his 1985 film tracing the legacy of American H-bomb tests in the Marshall Islands through a synthesis of interviews, and observational and archival footage. We see Soviet landmines being assembled and laid, surgical operations to save legs torn apart, and US cluster bombs being dropped. Perhaps the most mind-boggling moment, reminiscent of Dr Strangelove, comes when an American military official acknowledges an unfortunate oversight that has seen the US dropping food packages the same colour as cluster bombs. Framing this material with glimpses of mine awareness classes for young Afghans and interviews with Habiba and her husband moves Landmines beyond any narrowly political agenda.

Habiba’s husband Shah, an ex-Mujhadin soldier, is nothing like the conventional image of a rabid ideologue. Like Habiba, he has never been to school and earns a pittance repairing shoes on the street. Yet he is capable of calm reflection on Afghanistan’s history of being traded between, as O’Rourke puts it, “so many dirty hands”, and the responsibility of all parties for the devastation wrought by landmines in his country.

Summing up the film’s appeal, O’Rourke observes: “This couple are so interesting. Wouldn’t you want to have them at your Saturday barbecue? And the sexuality that subsumed that house–they were a sexy couple.” If that’s more compelling than controversial, it was reassuringly provocative to hear O’Rourke say towards the end of our interview that documentary “does attract, especially at the level of academia, a certain level of really anal aficionado.” I’ll wear that like a badge of honour.

Landmines–A Love Story, director and producer Dennis O’Rourke, 2005, distributed by Ronin Films. Landmines premiered at the Adelaide Film Festival in February and will be released in cinemas nationally on May 5.

RealTime issue #66 April-May 2005 pg. 25

© Tim O'Farell; for permission to reproduce apply to realtime@realtimearts.net

Guy Sherwin, Film performance with mirrored screen, 1976/2003

For artists like myself born in the 1970s, the activities of that decade can seem elusive, utopian and fascinating. Seemingly uncompromised by the pull of the art market, 1970s projects were remarkable for their clarity of intention and simplicity of execution. Concepts travel across time and space to the present, carried only by rudimentary texts and a few grainy black and white photos. The remnants of the processes of artists like Vito Acconci, Valie Export and Stephen Willats continue to inspire current generations who utilise and plunder their work as models for political, aesthetic and social action. But how much do we actually know about what went on? Can we trust the documents left behind?

My own particular interest in the 1970s has recently revolved around a ‘movement’ called Expanded Cinema. I use the term ‘movement’ loosely because, like minimalism or conceptual art, Expanded Cinema describes plenty of different activities in many different countries, and was not always a term used by the artists themselves. However, it is relatively safe to say that Expanded Cinema refers to that field of art in which artists and filmmakers sought to ‘expand’ the terms and conditions of what film could be. In addition, many artists were concerned with making transparent the components of the cinematic apparatus, and creating a live experience with the viewing audience, rather than merely replaying pre-edited footage. In that sense it sits quite comfortably in the company of much avant garde art of the 1960s and 70s which was redefining its own limits: paintings became sculptural and vice versa, and each of these began to incorporate performance, and the merging of art and life. Expanded Cinema, for its part, utilised multiple simultaneous projections, the incorporation of the ambient space (installation) and live performance elements. Thus, Expanded Cinema is a legitimate, although (in this country) little known, precursor to today’s ‘new media’ art.

Many artists who embraced Expanded Cinema, including Anthony McCall, William Raban, Malcolm Le Grice and Valie Export have said that they came to the form as a response to the comparatively stable nature of the Hollywood-run film industry. Le Grice, in a lecture accompanying a recent Export retrospective exhibition in London, referred to the film industry of the 1920s as having “contracted” cinema’s potential. The Expanded Cinema artists saw themselves as restoring the dynamism and experimentation cinema had possessed prior to being standardised in a feature-length narrative form.